The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V.1.1.. |

| V.1.2. |

| V.1.3. |

| V.1.4. |

| V. 2. |

| V.2.1. |

| 10. |

| 10. |

| V.2.2. |

LÖJSTA, GOTLAND, SWEDEN |

| V. 3. |

| V.3.1. |

| V.3.2. |

| V.3.3. |

| V. 4. |

| V.4.1. |

| V.4.2. |

| V.4.3. |

| V. 5. |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

| V. 6. |

| V.6.1. |

| V.6.2. |

| V.6.3. |

| V.6.4. |

| V. 7. |

| V.7.1. |

| V.7.2. |

| V.7.3. |

| V.7.4. |

| V.7.5. |

| V.7.6. |

| V. 8. |

| V.8.1. |

| V.8.2. |

| V.8.3. |

| V.8.4. |

| V.8.5. |

| V.8.6. |

| V.8.7. |

| V.8.8. |

| V. 9. |

| V.9.1. |

| V.9.2. |

| V.9.3. |

| V. 10. |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. |

| V. 11. |

| V.11.1. |

| V.11.2. |

| V.11.3. |

| V. 12. |

| V.12.1. |

| V.12.2. |

| V.12.3. |

| V. 13. |

| V.13.1. |

| V.13.2. |

| V. 14. |

| V.14.1. |

| V.14.2. |

| V. 15. |

| V.15.1. |

| V.15.2. |

| V.15.3. |

| V.15.4. |

| V. 16. |

| V.16.1. |

| V.16.2. |

| V.16.3. |

| V.16.4. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| V.18.1. |

| V.18.2. |

| V.18.3. |

| V.18.4. |

| V.18.5. |

| VI. |

| VI. 1. |

| VI.I.I. |

| VI.1.2. |

| VI.1.3. |

| VI.1.4. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI.2.1. |

| VI.2.2. |

| VI.2.3. |

| VI.2.4. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI.3.1. |

| VI.3.2. |

| VI.3.3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI.4.1. |

| VI.4.2. |

| VI.4.3. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

LÖJSTA, GOTLAND, SWEDEN

The second house, a structure of more normal proportions,

85 feet by 33½ feet (26 m. × 10.5 m.), was excavated in

the summer of 1929 in the vicinity of castle Lojsta in

Gotland (fig. 291A-C).[104]

It was the same construction type

except that here the roof-supporting posts were not sunk

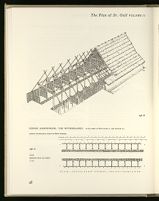

298.B EZINGE (GRONINGEN), THE NETHERLANDS. CATTLE BARN OF Warf-LAYER IV, 2nd CENTURY B.C.

[author's reconstruction, drawn by Walter Schwarz]

298.A PLAN

REDRAWN FROM VAN GIFFEN

1:150

299. EZINGE (GRONINGEN), THE NETHERLANDS. CATTLE BARN OF Warf-LAYER IV, 2nd CENTURY B.C.

[excavation photo by courtesy of A. E. Van Giffen]

This building, like those unearthed above and beneath it, owes its magnificent state of preservation to the fact that each settlement stratum in

which houses were buried in the course of successive inundations was sealed by sterile layers of sand and clay deposited after flooding, sealing

their content against the infiltration of air and thus protecting it from decay. The roof-supporting posts of oak, the braided walls and cross

partitions (wattled saplings of birch) were preserved to a height of 4 feet. The manure mats were found to be in such good condition that they

could be walked upon without breaking. The building was 29 feet wide (7.20m) and over 75 feet long (23m) but was never excavated to its full

length. Its construction was identical with that of the houses found in the earlier Warf layers (figs. 293-297).

The systematic division of the aisles into stalls, together with the absence of any fireplaces, suggests that it was used for the stabling of livestock

exclusively. Since every stall had room for two head of cattle, this barn must have been able to hold at least 48 animals, striking evidence of

the economic wealth of these early shoreland farmers. Livestock entered and left the building through doors in the two narrow ends—a feature

found in many other early Iron Age houses (figs. 304, 310, 312, 315, 316), and today in the Lower Saxon Wohnstallhaus and the Frisian

Los-hus, modern descendants of this building type.

PRE- & PROTOHISTORIC CARPENTRY JOINTS

300.A

300.B

300.C

300.D

[after Zippelius, 1954, figs. 1, 2, & 5]

A. Forked posts (Neolithic)

B. Post with slit head

C. Mortice and tenon joint in post and plate assemblage

(Neolithic)

D. Mortice and tenon joint in post and ground sill assemblage

(Bronze Age)

stones were still in their original position (fig. 291A). The

posts themselves had disappeared. Rising freely from stones

as they did, they could only retain their vertical position by

being framed together at the top by means of cross beams

and long beams. Slight irregularities in the longitudinal

alignment of the posts suggested that the cross beams lay

underneath the long beams. The excavators felt so sure of

their interpretation of these conditions that they undertook

to reconstruct the entire hall on its original site (figs. 291B

and C). Some of the details of this reconstruction have since

been questioned, but the doubts amount basically to no

more than that in the original house the walls were probably

a little higher than they are shown at present.[105] The

pottery found in the house suggests as period of construction

the third century A.D. In the fifth century, for unknown

reasons, the hall appears to have been abandoned.

In the two decades that followed probably more than

sixty houses of the Lojsta type were unearthed on the

islands of Gotland and Öland, on the mainland of Sweden,

in Norway and in Denmark,[106]

and, last but not least, in

Iceland, the country whose literary tradition introduced us

to this type of dwelling.

The Swedish material is surveyed in exemplary publications, such

as the work of Nihlen and Böethius on the Iron Age farmsteads of Gotland,

and the corresponding volume by Stenberger on the Iron Age

farmsteads of Öland (both published in 1933), and the magnificent

collective work on Vallhagar, edited in two volumes by Stenberger and

Klindt-Jensen, 1955.

The Norwegian material excavated prior to 1942 is summarized in

Grieg, 1942.

For the Danish material prior to 1937 see Hatt, 1937. For later material

see Nørlund's splendid account on Trelleborg, published in 1948,

and the excavation reports by Hatt and others listed in Hatt's latest

great work, on the Iron Age village of Nørre Fjand, published in 1957,

as well as a number of articles that have appeared during the last two

decades in the Danish series Fra Nationalmuseets Arbejdsmark (Copenhagen,

Nationalmuseet, 1928ff).

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||