The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V.1.1.. |

| V.1.2. |

| V.1.3. |

| V.1.4. |

| V. 2. |

| V.2.1. |

| 10. |

| 10. |

| V.2.2. |

| V. 3. |

| V.3.1. |

| V.3.2. |

| V.3.3. |

| V. 4. |

| V.4.1. |

| V.4.2. |

| V.4.3. |

| V. 5. |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

| V. 6. |

| V.6.1. |

| V.6.2. |

| V.6.3. |

| V.6.4. |

| V. 7. |

| V.7.1. |

| V.7.2. |

| V.7.3. |

| V.7.4. |

| V.7.5. |

| V.7.6. |

| V. 8. |

| V.8.1. |

| V.8.2. |

| V.8.3. |

| V.8.4. |

| V.8.5. |

| V.8.6. |

| V.8.7. |

| V.8.8. |

| V. 9. |

| V.9.1. |

| V.9.2. |

| V.9.3. |

| V. 10. |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. |

| V. 11. |

| V.11.1. |

| V.11.2. |

| V.11.3. |

| V. 12. |

| V.12.1. |

| V.12.2. |

| V.12.3. |

| V. 13. |

| V.13.1. |

| V.13.2. |

| V. 14. |

| V.14.1. |

| V.14.2. |

| V. 15. |

| V.15.1. |

| V.15.2. |

| V.15.3. |

MONASTIC ECONOMY AND WATER POWER

UNDER ST. FRUCTUOSUS |

| V.15.4. |

| V. 16. |

| V.16.1. |

| V.16.2. |

| V.16.3. |

| V.16.4. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| V.18.1. |

| V.18.2. |

| V.18.3. |

| V.18.4. |

| V.18.5. |

| VI. |

| VI. 1. |

| VI.I.I. |

| VI.1.2. |

| VI.1.3. |

| VI.1.4. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI.2.1. |

| VI.2.2. |

| VI.2.3. |

| VI.2.4. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI.3.1. |

| VI.3.2. |

| VI.3.3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI.4.1. |

| VI.4.2. |

| VI.4.3. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

MONASTIC ECONOMY AND WATER POWER

UNDER ST. FRUCTUOSUS

The date of the hammer is unknown.[523]

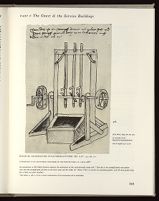

Local tradition PERSPECTIVE VIEW [redrawn after Meringer, 1909, fig. 35] Meringer interpreted the two trip-hammers of the Mortar House of

ascribes it to "Romanesque period" (edad romanica).

454. PLAN OF ST. GALL. TILT-HAMMER

the Plan as being activated by a cam block formed on a single

timber extending, as part of an axle shaft, from the hub of the

waterwheel.

have been an integral part of the monastic economy of the

time of San Fructuosus (d. 665).[524]

This view is not so

455. SPECHTSHART. FLORES MUSICAE

STRASSBOURG, 1488, fol. 7v

[courtesy of the University Library, Freiburg i. Br., Germany]

The woodcut shows an iron forge with a water-powered tilt-hammer

activated by a cylindrical cam block mounted on the axle of a waterwheel.

Two blacksmiths forge iron on an anvil with the hammer's

aid; behind them Pythagoras weighs hammers. In the background,

Tubal chisels musical notes into a column, representing Pythagorean

philosophical preoccupation with order, number, and harmony of the

spheres of the Ptolemaic universe (cf. I, 231, fig. 187).

seventh century, as has been shown in the preceding

chapter, was the great century of systematic application of

water power to milling in the economy of coenobitic

monachism.[525] The development was spurred by the need to

provide great quantities of flour for the sustenance of large

numbers of men whose religious activities required that they

be freed from certain common forms of labor, in order to

devote themselves to the more serious task of serving God

in prayer and chant. It is not an unreasonable conjecture

that the same need may also have fostered the invention or

adoption of the cam which made it possible to harness water

for tasks requiring the crushing blow of a rising and falling

mechanical hammer. It is quite possible that this idea (or

its adoption) was first conceived in connection with iron

works where the brutal blow of a hydraulic stamp offered

advantages highly superior to those that could be derived

from its use in the lighter task of crushing grain or of

fulling cloth. The banks of the rivers in the mountains of

Eastern Leon, where San Fructuosus founded his first

monasteries, carry iron deposits important enough to be

mentioned by Pliny the Elder and other Roman writers;[526]

numerous localities in this area, now in ruins or deserted,

carry even today the name herrería (iron forge).[527]

The Fructuosan monastic economy formed an ideal

ambiance for the invention of such a power mechanism. It

created a sudden and vast demand for agricultural tools by

converting virtually overnight deserted valleys into densely

populated rural communities, formed not only by the

multitude of monks that settled in the monastery itself, but

in addition by a veritable army of secular followers who

were allowed to establish themselves as tenants in the vast

stretches of land which the monastery owned in the valleys

and mountains around it. Among them were members of

the former household of San Fructuosus (whose paternal

inheritance was enormous), magnates from the royal court

with their entire families, soldiers from the Visigothic

army who fell under the spell of the saint, and in a mystical

commotion that had no precedent, followed him in such

numbers that their chieftains found themselves compelled

to legislate against such wholesale desertion of the army

and flight into the country.[528]

A blacksmith capable of

converting ore into iron with the aid of water power and

shaping it into usable tools could meet the demands created

by such a sudden population increase in the country, and the

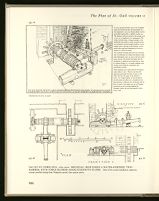

456. MUNICH, BAYERISCHE STAATSBIBLIOTHEK. MS. LAT. 197, fol. 10r

ATTRIBUTED TO AN ANONYMOUS ENGINEER OF THE HUSSITE WARS, CA. 1472-1486[529]

An annotation in Old High German explains the mechanism of this vertical-pestle stamp mill: "Item das is ain stampff damit man pulver

stost unn dye stampff gent all drey in ain loch, ainer auf der ander ab" (Item: This is a mortar for pounding powder, and all three pestles drop

into a hole, one after another).

VALLEY OF COMPLUDO, LEÓN, SPAIN. MEDIEVAL IRON FORGE & WATER-POWERED TRIP-HAMMER,

WITH FORGE BLOWER ASSOCIATED WITH FLUME. Date of the initial installation unknown,

concept possibly dating from Visigothic period. See caption above.

457.A

PERSPECTIVE VIEW

In 1975 we paid another visit to the Compludo

forge and discovered that the trip-hammer we

first inspected in 1970 was being rebuilt, and the

waterwheel replaced by a slightly sturdier one.

The hammer had been moved to the outside yard

to serve as a template for its replacement. The

sturdy cammed trunk, strongest member of the

mechanism and subject to great torsional strain,

was considered in good enough condition to serve

another span in the life of the hammer. It had

earlier been reinforced lengthwise by iron bars

banded to it with iron hoops.

The carpenter directing the work was convinced

that in continuous use, wheel and hammer would

need replacement every 40 years, the main trunk

every century. He shared local belief that the

mechanism is medieval and would tend to retain

its original design for a virtually indefinite span

of time, even though its components were

periodically renewed.

These drawings were made with aid of measurements

taken in 1975. They do not show the

apparatus governing the flow of water to the

wheel and thus the speed of the hammer's

action. For rough sketches of that mechanism

and the means by which air is drafted into the

forge furnace, a function also associated with the

flow of water to the wheel race, we still depend

exclusively on the drawing published by

Gonzáles (1966, 46) and reproduced by Horn

(1975, 245).

457.B

457.C

457.D

to the adoption of devices facilitating their production.

The Romans, it is generally conceded, did not make any

use of water-powered trip-hammers transmitting the

rotational movement of the wheel and its axle into the

vertical beat of a recumbent hammer by means of cogs.

China, unquestionably is the prime inventor. But the Plan

of St. Gall attests that at the beginning of the ninth century

such mechanisms were, even in the West, well known and

widely employed. This seems to vitiate the theory of its

westward diffusion by Marco Polo and suggests that the

knowledge of this invention came to Europe in the wake of

contact established with the Far East, in the fourth and

fifth centuries A.D. by the invasion of the Huns and other

Asiatic tribes, with whom the Visigoths were in close, and

often mortal, association over long periods of time.

In an earlier study (Horn, 1975, 254 note 13) I expressed the hope

that radiocarbon analysis of the timbers of axle, hammer, and waterwheel

might in the future help establish the age of the hammer. Returning to

the site in 1974, I discovered that all these timbers were in process of

being replaced. The carpenter in charge of the work held the view that

because of the heavy strain imposed upon these members when in daily

operation, such repairs would have to be made every 40 to 50 years. This

does not militate against the assumption of a medieval origin for the

mechanism on this site.

"La [herrería] de Compludo signe siendo un monumento vivo, casi

intacto, que bien pudo connocer los tiemposos frutusianos." Gonzáles,

op. cit., 44.

Gonzáles, loc. cit., lists one in the vicinity of Vega de Valcarce;

another one in Puente Petra (near Oencia); a third one in Marciel (near

Quintana de Fuseros) which gave its name, Ferreria, to a village that has

since disappeared; a fourth one in Paradaseca. In a fifth, the herreria of

Montes (near San Clemente de Valdueza) the stamping mechanism is so

well preserved as to permit its reconstruction.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||