VI.3.2

TRADITION

Many autonomous Benedictine monasteries adopted the

customs of Cluny. Christchurch, Canterbury, for instance,

was built by Lanfranc, who was previously prior of the

Abbey of Bec in Normandy. The customs of Bec are true

to the earlier customs of Cluny which William of Volpiano

brought to Fécamp and other northern monasteries at the

beginning of the eleventh century. The monastic constitutions

which Lanfranc later wrote are similar to the customs

composed under Odilo between 1030 and 1048.[94]

There was

continual interaction between Cluny and the autonomous

English houses and in many cases Cluny must have transmitted

the reform ideas promulgated at Aachen.

Earlier ties, however, also connect the English monasteries

with the synods of Aachen. The monastic revival

begun by Dunstan in the second half of the tenth century

was based on the continental monastic tradition of Benedict

of Aniane.[95]

While in exile Dunstan took refuge in the monastery

of Blandium at Ghent in 954. Around 970 a synod

under Dunstan's guidance was called at Winchester to

establish a common way of life for English monasteries

under the patronage of King Edgar. The procedure and

provisions of the meeting consciously imitated those of the

synod at Aachen, directed by Benedict of Aniane in 817

under the auspices of Louis the Pious. In the presence of

monks from Fleury and Ghent the Regularis Concordia, a

code based on the Ordo Qualiter and the Rule for Canons

and Capitula of Aachen, was drawn up.[96]

About forty monasteries

were founded under this revival between 957 and

the Conquest, but no architectural remains seem to indicate

the arrangement of the conventual buildings before the last

phase of this revival during the reign of Edward the Confessor.

At this time both the style of Norman architecture

(exemplified by Westminster Abbey, consecrated in 1065)

as well as the typical institutions of Norman monasticism,

that clearly characterize post-Conquest England, were

already established.[97]

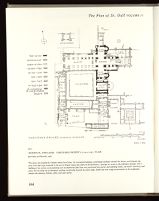

In the Post-Conquest English Benedictine monasteries

of the eleventh and twelfth century, the east range of the

cloister contains the dormitory; the south range, the refectory;

and the west range, the cellar, as on the Plan of St.

Gall and at Cluny II.

These relationships have become traditional and binding.

Whenever the site permitted in the few examples that

remain the peripheral houses and workshops were arranged

as they were on the Plan of St. Gall. The entrance to the

monastery is usually to the west of church and cloister. The

mill and bake house are adjacent to the kitchen, as on the

plan of the waterworks of Christchurch, Canterbury (Kent),

shown above in figure 52. The infirmary, its chapel and

cemetery are to the east of the cloister, as can be seen at

Christchurch and at Bardney Abbey, Lincolnshire, (fig.

516).

In some particulars the English plans reflect the arrangement

on the Plan of St. Gall even more closely than Cluny

II. In all of these monasteries the east range of the cloister

is aligned with the southern transept-arm and the cloister

forms a regular square. Whenever the location of the

twelfth century kitchen is known, as on the Canterbury

plan (fig. 52), it is isolated from the refectory and connected

with the south range by passageways, as it was on the

Plan of St. Gall; while at Cluny II it may have been part

of that range. As at St. Gall, there is only one kitchen;

Cluny had two.

Other aspects seem closer to the Plan of St. Gall, but

they are not well enough established to allow generalization.

In some English monasteries such as Thetford (fig. 517),

part of the undercroft of the dormitory may still have served

as the warming room, but it is considerably reduced

in area and pushed to the southern part of the range.

There is some indication that in later English monasteries

night stairs connected the dormitory with the southern

transept arm of the church, as it did on the Plan of St. Gall.

In Cluny (fig. 515) such a connection probably would not

have existed if the east range, as Conant assumes, was

severed from the transept. In Cistercian planning the night

stairs reappear in the place where they were indicated on

the Plan of St. Gall. Since the elements that Cistercian

planning have in common with the Plan of St. Gall could

only have been transmitted by later Benedictine monasteries,

they must have been more common in Benedictine

planning than present remains indicate.[98]

Our survey of English monastery plans also reveals that

the dimensions of the cloister square comply with the standards

set by the Plan of St. Gall and with the stipulation

made by Hildemar of Corbie (ca. 845) that a cloister yard

should never be less than 100 feet square.[99]

In the Benedictine

and Cluniac English monasteries the cloister yard, as a

rule, is not smaller than this, though it is sometimes larger.[100]

These basic similarities between the English monasteries

and the Plan of St. Gall remain constant wherever the

natural conditions of the site permit. When exceptions occur

they can be explained either by the topography or by restrictions

imposed by the architectural surroundings.[101]

In

England such irregularities are more common in Benedictine

than in Cistercian monasteries because the Benedictines

rarely had a virgin site on which to build and were

often settled near cities, while the Cistercians chose isolated

areas, a fact which may be primarily responsible for

what, in contrast to Cistercian conformism, appears to be

a lack of uniformity in Benedictine planning.