V. 13

THE CEMETERY AND ORCHARD

To the side of the Novitiate, the home of the incoming

monks, and in convenient proximity to the Infirmary and

the House of the Physicians, is the monastery's burial

ground. It is a large field 80 feet wide and 125 feet long,

enclosed by walls or hedges, with only a single entrance to

the west facing the monks' cloister (fig. 430).

The grounds of the Cemetery served, in addition, as an

orchard, and this dual role of giving rest to the dead under

the shadow of the Cross as well as furnishing the living

with delectable fruit is poetically expressed in a distich,

inscribed into a large square enclosure in the center of the

cemetery, which designates the location of a monumental

cross:

Inter ligna soli haec semp̶ s̄cissima crux ÷

In qua p̶p̶ & uae poma salutis olent

Among the trees of the soil, always the most

sacred is the Cross

On which the fruits of eternal health are fragrant

V.13.1

THE CEMETERY

There are fourteen burial plots, each 6¼ feet wide and 17½

feet long.[452]

They are identified by the distich:

Hanc circum iaceant defunta cadauera fr̄m̄

Qua radiante Iterum. Regna poli accipant'

Around this [cross] let rest the dead bodies

of the brethren

And through its radiance they may attain again

the realm of heaven

The death and burial of a monk was a matter of intense

concern to the entire community, as may be inferred from

the moving descriptions of the last hours of the monks

Wolo, Ratpert and Gerald in Ekkehart's IV Casus sancti

Galli or the latter's poetic account of the death of his teacher

Notker Labeo in his Liber Benedictionum.[453]

An English

consuetudinary of the end of the tenth century, the Regularis

concordia of St. Dunstan, describes the share which

the community had in the death of one of its brothers as

follows:

When the sick brother feels his strength ebbing, he makes this

known to the convent through the master of the infirmary. Whereupon

the priest who celebrates the morning mass, accompanied by

his attendants, will administer the holy eucharist. Preceded by

monks carrying candles and incense, the entire congregation visits

the sick, chanting the penitential psalms, the litanies of the saints,

and the prescribed orations. Then the sick receives his last unction,

yet only on the first day; thereafter he receives the communion.

If he recovers his strength the daily visits stop. If his condition does

not improve, the visits are continued to the end.

When the patient [begins] his death struggle, the sounding board is

rung so that all can come together to be at his side in this extreme

moment. Immediately the prayers of the commendation of the

soul are said, the Subvenite, sancti Domini and the sequence prescribed

by the Ordo commendationis.

Upon expiration those who are in charge of this task will wash

the body and wrap it into its proper clothing, i.e., his shirt, his

cowl, his gaiters, and his shoes, whatever is customary in the order

to which the deceased belongs. If he be a priest, in addition, the

stole will be placed upon his cowl, if this seems appropriate. This

being done, the body is carried into the Church to the chant of the

psalms and the ringing of the bells.

If death comes at night before dawn or matin and there is time

for all the preparations necessary for burial, he will be placed into

his grave that same day, after the celebration of mass and before the

brothers take their meal. Otherwise, brothers will be designated to

watch in groups over the body during this day and the night which

follows. Psalms will be sung without interruption until the body is

rendered to the earth. After the burial the brothers return to the

Church, chanting the seven penitential psalms for the deceased.

They complete the psalms lying prostrate before the holy altar.[454]

V.13.2

THE ORCHARD

The spaces between the burial plots are planted with fruit

trees. Their location is indicated by thirteen tree-symbols

which, save for the thickness of their stems, resemble tendrils

rather than trees. The fact that one of them is associated

with the names of two different species (sorbarius and

mispolarius) suggests that in each case there was meant to

be a group of plants rather than an individual specimen.

This is also suggested by the largeness of the space for

planting left between the burial plots, which in some cases

amounts to as much as 12½ feet by 40 feet. The names of

the trees have been tampered with by the same hand that

tried to revive the erased titles of the large anonymous

building in the northwest corner of the monastery.[455]

As

there, the chemical substance used in this attempt has left

thick blue streaks in the parchment. This action damaged,

but did not destroy, the names of the trees. Listed in the

sequence in which they were written by the scribe, from

top to bottom, and in columns, moving from left to right,

they are:

| 1. |

mal[arius] |

apple (malus communis L.) |

| 2. |

perarius |

pear (pirus communis L.) |

| 3. |

prunarius |

plum (prunus domestica L.) |

| 4. |

sorbarius |

service tree (sorbus domestica L.) |

| 5. |

mispolarius |

medlar (mespilus germanica L.) |

| 6. |

laurus |

laurel (laurus nobilis L.) |

| 7. |

castenarius |

chestnut (fagus castanea L.) |

| 8. |

ficus |

fig (ficus carica L.) |

| 9. |

guduniarius |

quince (cydonia vulgaris L.) |

| 10. |

persicus |

peach (prunus persica L.) |

| 11. |

auellenarius |

hazelnut (corylus tubulosa L.) |

| 12. |

amendelarius |

almond (amygdalis communis L.) |

| 13. |

murarius |

mulberry (morus nigra L.) |

| 14. |

nugarius |

walnut (juglans regia L.)[456]

|

Of the fourteen listed species the apple, the pear, the

plum, the quince, and the peach are fruit trees in the proper

sense of the term; the others—the medlar, the chestnut,

the hazelnut, the mulberry, the walnut, the almond, and

the service tree—in the broader sense. Two of the trees

listed, the fig and the laurel, are not suited to a northern

climate. All of these fourteen trees are also listed in the

repertory of plants which the Capitulare de villis prescribes

as mandatory for the gardens in the king's estates. The

inclusion in this manual for the management of crown estates

of a considerable number of plants and trees that require

a Mediterranean climate had formerly led to the belief that

it was issued for the kingdom of Aquitaine.[457]

Recently this

attribution has been questioned,[458]

and the entire problem of

the presence on the Plan of St. Gall, as well as in the

Capitulare de villis and other Carolingian sources, of plants

not suited for a northern climate is now being interpreted

as an expression of literary classicism.[459]

The yield of the fruit trees in the Cemetery could not

have met all the needs of a community of an estimated

250 to 270 mouths. The monastery has a special house for

the drying of fruit (locus ad torrendas annonas), where

staples were produced which enabled the Kitchener to

bridge the dietary shortages in the critical winter months

when the fields and gardens were barren. The bulk of the

fruit, however, that was needed for that purpose must have

come from outlying orchards, managed either by the abbey

itself or by tenants.

The business accounts of the monastery of St. Gall tell

us of the deliveries of nuts from Rorschach, of apples from

a place called Bachwille, and from an orchard maintained

at a place called Muolen.

The contribution made to European horticulture by

skills practiced by monks in the growth and propagation of

fruit trees cannot be overestimated. The number of indigenous

fruit trees north of the Alps was limited, and the

native fruit too small and too bitter to be eaten raw. They

could be used for the preparation of fermented beverages

(in Old and Middle High German sources we read of

epfildrac [cider] and slehendrac [an alcoholic beverage made

of sloe]),[460]

but for fruit to be served at the table the indigenous

trees had to be improved through selective breeding

and grafting. The knowledge of this art was acquired

by the inhabitants of transalpine Europe from the Romans;

it spread from Gaul along the Moselle into the Rhine

valley.[461]

The monasteries adopted this legacy and applied it

on a large scale. The orchards of the abbey became the

model for the orchards and gardens of their secular tenants;

and from them the knowledge spread to the tenants of the

secular lords.

*

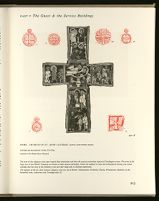

[ILLUSTRATION]

430.X ROME. CHURCH OF ST. JOHN LATERAN, SANCTA SANCTORUM CHAPEL

ENAMELLED RELIQUARY CROSS, 817-824

[courtesy of the Museo Sacro Vaticano]

The arms of the reliquary cross taper toward their intersection and show the concave extremities typical of Carolingian crosses. The arms of the

large cross in the Monks' Cemetery are drawn to show concave extremities. Given the evidence in coins and architectural carving, one cannot

conclude that the arms of the Cemetery cross owe their shape only to drafting mannerisms.

The registers of the St. John Lateran reliquary cross are, top to bottom: Annunciation, Visitation, Navity, Presentation, Baptism; on the

horizontal arms: Adoration and Transfiguration (?)

Drawn from silver coins: I, II, IV, V, struck 794-805; III, 768-72; VI: Cross

carved in stone closure slab (Musée Centrale, Metz, late 8th cent.)

Vertical and horizontal arms of the typical Carolingian cross taper slightly from

the outer ends to their intersection. The thick, stocky design of IV, less usual,

has a pronounced concavity at the extremities.

The stone cross, VI, of pronounced taper, has flat extremities. A common type

in architectural carving, it was much in vogue in Visigothic Spain. The

sculptured stone prevails over the cross with parallel sides.