The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V.1.1.. |

| V.1.2. |

| V.1.3. |

| V.1.4. |

| V. 2. |

| V.2.1. |

| 10. |

| 10. |

| V.2.2. |

| V. 3. |

| V.3.1. |

| V.3.2. |

| V.3.3. |

| V. 4. |

| V.4.1. |

| V.4.2. |

| V.4.3. |

| V. 5. |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

| V. 6. |

| V.6.1. |

| V.6.2. |

| V.6.3. |

| V.6.4. |

| V. 7. |

| V.7.1. |

| V.7.2. |

| V.7.3. |

| V.7.4. |

| V.7.5. |

| V.7.6. |

| V. 8. |

| V.8.1. |

| V.8.2. |

| V.8.3. |

| V.8.4. |

| V.8.5. |

| V.8.6. |

| V.8.7. |

| V.8.8. |

| V. 9. |

| V.9.1. |

| V.9.2. |

| V.9.3. |

| V. 10. |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. |

| V. 11. |

| V.11.1. |

| V.11.2. |

| V.11.3. |

| V. 12. |

| V.12.1. |

| V.12.2. |

| V.12.3. |

| V. 13. |

| V.13.1. |

| V.13.2. |

| V. 14. |

| V.14.1. |

| V.14.2. |

| V. 15. |

| V.15.1. |

| V.15.2. |

| V.15.3. |

| V.15.4. |

| V. 16. |

| V.16.1. |

| V.16.2. |

| V.16.3. |

| V.16.4. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| V.18.1. |

| V.18.2. |

| V.18.3. |

| V.18.4. |

| V.18.5. |

| VI. |

INTRODUCTION |

| VI. 1. |

| VI.I.I. |

| VI.1.2. |

| VI.1.3. |

| VI.1.4. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI.2.1. |

| VI.2.2. |

| VI.2.3. |

| VI.2.4. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI.3.1. |

| VI.3.2. |

| VI.3.3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI.4.1. |

| VI.4.2. |

| VI.4.3. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

INTRODUCTION

THE sections that follow deal in a tentative form with the effect that the ideas embodied in the Plan of St. Gall

had upon later monastic planning. An exhaustive treatment of such effects would require a separate book; nevertheless

we will attempt to illuminate the question by concentrating on a selected group of later monasteries and by

discussing only certain basic aspects of a far larger and more subtle complex of problems. Foremost in consideration

are three questions that have always been of concern to the historian of monastic planning:

1. To what extent did Abbot Gozbert and his successors adhere to the Plan when they rebuilt the monastery

of St. Gall from 830 onwards?2. Did the concepts embodied in the Plan establish a tradition?

3. If this was the case, to what extent was this tradition modified by innovations deriving from new customs

in the Cluniac, autonomous Benedictine, and Cistercian monasteries of the eleventh and twelfth centuries?

FOR the treatment of the first of these three questions I am responsible. The examination of the two others,

discussed in chapters 2 through 5, is based on a master's thesis written by Carolyn Malone and completed in

time to allow its results to be included in this book. The research embodied in these chapters and its presentation

are hers. I have made some minor additions, including all of the extended figure captions. We conclude with a

brief Epilogue, and a review of excavations beneath Gozbert's church, based on a report by architect Dr. H. R.

Sennhauer, in charge of excavations.

W. H.

506.A ST. GALL SITE OF THE FORMER MONASTERY WITH ITS PRESENT BUILDINGS

AIR VIEW FROM NORTHWEST LOOKING SOUTHEAST

The Carolingian church and virtually all other monastic buildings were completely rebuilt between 1755 and 1767/68, but the street pattern

and alignment of houses clustering around the church even today reflect, with amazing accuracy, the boundaries of the original monastery site.

The Baroque church is co-axial with the three preceding medieval churches (see fig. 513.A-B) and almost identical with them in width and

overall length. Double-apsed like the church of the Plan of St. Gall, it is, like the latter, without façade. By contrast its towers, flanking the

apse at the eastern end of the building, do not guard the western entrances to the church, but rather signal to the outside world the location of

the high altar and the relics of St. Gall.

506.B ST. GALL. SITE OF THE FORMER MONASTERY WITH ITS PRESENT BUILDINGS

AIR VIEW FROM SOUTHEAST LOOKING NORTHWEST

The primary reason for construction of the present church owed to the sack of the monastery in 1712 by the Protestant citizenry of Zürich and

Bern. The reconstruction was undertaken with palatial magnificence, and a breathtaking aesthetic exuberance that derived its vitality from a

new alliance of the landed aristocracy of Europe with Catholicism.

In the wake of this accord spread one of the most lavish architectural styles of all ages. The designers of the new church endeavored to reconcile

the directionalism of the traditional western church with a concept of centrality by arresting its longitudinal flow midway in the swirl of a

domed rotunda, and by merging nave and aisles into a single undulating body of space.

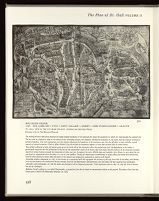

507. MELCHIOR FRANK.

1596 DIE LOBLICH * STAT * SANT GALLEN * SAMBT * DEM FURSTLICHEN * CLOSTR

ST. GALL, VIEW OF THE CITY FROM THE EAST. ETCHING ON IRON (40 × 61cm)

[Courtesy of the St. Gall Historical Museum]

The etching portrays with great precision the wedge-shaped boundaries of the elevated site (lower left quadrant) on which St. Gall founded his original cell.

The site owed its distinctive shape to the courses of two converging streams, the Steinach, skirting the monastery to the south, and the Irabach, forming its

northern boundary. The river escarpments not only sharply delineated the boundaries of the monastery site, but also afforded, at least initially, a good

measure of natural protection. Even in Abbot Gozbert's day (816-836) the monastery appears to have been enclosed only by wattle fences.

The earliest settlement of serfs and tenants grew up on the north side of the monastery where the ground was level. Its dependence on the abbey is

permanently engraved into the architecture of the city by the semicircular course of its streets, that even today hug the contours of the monastery grounds.

Search for urban freedom strained the relationship of abbey and city throughout the entire Middle Ages and reached a first climax in 1475 when the city

purchased its independence from the abbey at a cost of 7000 guilders. During the Reformation (commencing in 1524), abbot and monks were forced into

exile but were allowed to return when the power of the citizens was temporarily weakened by warfare with Kapel.

Increasing conflicts culminated, in 1567, in the erection of a separation wall that segregated the territory of the city from that of the abbey, and thereby

froze into permanency the confessional division brought about by the Reformation. Henceforward, city and abbey led their separate lives politically,

culturally, and economically. In 1798 the abbey was divested of all its temporal possessions. Total supression came in 1805. In 1847 the church became

the seat of a bishopric.

Melchior Frank's etching is a so-called Planprospekt, a perspective from the air based on measurements taken on the ground. The plate is lost; the only

known print is held in the Historiches Museum, St. Gall.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||