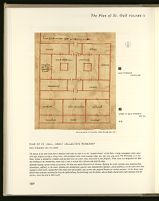

V.11.2

THE GREAT COLLECTIVE WORKSHOP

Not counting the large untitled building in the northwestern

corner of the monastery, this is the most spacious

of the guest and service buildings of the Plan of St. Gall.

It consists of a main building and an annex, separated from

one another by a narrow court (fig. 419). The main building

is 55 feet wide and 80 feet long; the annex is 27½ feet by

80 feet. Together with their court, which is 10 feet wide,

these installations cover a surface area of 7,200 square feet.

Their function is explained by the hexameter:

Haec sub se teneat fr̄m̄ qui tegmina curat[417]

Let him take charge of these things who takes

care of the brothers' apparel.

The monastic official referred to in this title is the Chamberlain,

who is in charge of the production and maintenance of

the monastery's material supplies and tools, including the

community's footwear and clothing.[418]

THE MAIN BUILDING

The chamberlain's hall and workshop

The layout of the main house (fig. 419) is similar to that of

the Outer School. In both cases, the center hall is divided

by a median wall partition into two equal halves, each

furnished with its own hearth and louver; however, in the

Collective Workshop this partition extends across the entire

width of the hall and has no doors between the two rooms

thus segregated. Each has its separate entrance and exit,

yet both are designated by the collective title, "the chamberlain's

hall and workshop" (domus & officina camerarii).

The coupling of the denotation domus and officina makes

clear that the two center spaces of the Great Collective

Workshop perform the dual function of serving both as

living room and as supplementary work space.

It would be unreasonable to assume that the Chamberlain,

who was in charge of the work performed in this house,

also resided and slept there.[419]

His rank in the monastic

polity, had he shared quarters with the workmen, would

have called for a private bedroom with corner fireplace and

private toilet facilities, which do not exist in this building.

The Chamberlain either slept in the Dormitory for the

regular monks, or, more likely, shared the sleeping quarters

of the abbot, to whom he was closely attached not only by

grave responsibilities of his office, but also—at least in

some of the monastic orders—by certain specific duties of

a personal nature.[420]

The two central halls of the house,

designated as "the chamberlain's hall and workshop," are

the rooms where the chamberlain conferred with his craftsmen,

assigned workloads, and inspected the finished products.

They were also the place where the workmen, in their

hours of rest, could congregate around the open fire, prepare

and eat their meals.[421]

The designer of the Plan was aware of

the fact that the work performed in these rooms required

special lighting conditions, and he met this need with a

double set of louvers capable of flooding the interior of this

house with an abundance of light.

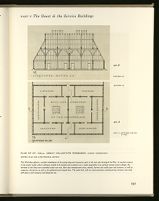

Crafts performed in peripheral workshops

Peripherally ranged around these two center spaces are

the quarters of the workmen, measuring 12½ feet by 32½

feet and 12½ feet by 30 feet, respectively. They are distributed

as follows: on the entrance side, to the left and right

of the vestibule, the "shoemakers" (sutores) and the "saddlers"

(

sellarii). Their duties require no further comment.

In the two lean-to's at the western and eastern end of the

house are the "grinders or polishers of swords" (

emundatores

† politores gladiorum) and the "shieldmakers" (

scutarii).

Their presence is not surprising in view of the monastery's

military obligations, discussed in an earlier chapter.

[422]

The

"grinders and polishers of swords" were probably also in

charge of the production of the monastery's cutlery and

other cutting tools.

[423]

This is suggested by the fact that this

work is not assigned to any other craftsmen listed on the

Plan. By the same token, the shieldmakers, too, may have

been involved in the manufacture of tools other than

shields. The two rooms in the southern aisle of the house,

to the left and right of the vestibule that gives access to

court and annex, are occupied by the "turners" (

tornatores)

and the "curriers" (

coriarii). The turners are the men who

manufacture the wooden bowls, dishes, and trays that are

used in eating, the handles of such tools as axes and hoes,

and perhaps the smaller pieces of furniture, such as cupboards

and chairs. Their work may also have included the

making of wooden sculpture.

[424]

The curriers dress and prepare

leather after tanning; they pare off roughnesses and

inequalities and make the leather soft and pliable. Since the

Plan does not provide for any special facilities for the manufacture

of parchment, it is probable that the curriers' workshop

was also the place where this important material was

made.

The stripping of hides, whether used for the production

of parchment or other commodities, depended on the

availability of water and lime, which was also needed by

the fullers who were quartered in the Annex. It is no accident

that the workshops of the curriers and the fullers face

each other on either side of an open court, where lime pits

and other baths can be installed easily.[425]

Presumptive number of craftsmen

There is no doubt in my mind that the aisles and leanto's

of the Great Collective Workshop were the sleeping

quarters for the men who worked there. This was the traditional

space for sleeping in this type of house.[426]

To what

extent the aisles and lean-to's were used additionally as

workshops would have depended on the number of men

they housed, and the amount of floor space left after they

were bedded. If beds were arranged in a single file along the

outer walls of the house, as is the case in most of the other

places of the Plan where beds are shown,[427]

the main house

could have accommodated twenty-eight workmen. Another

four men could have been established with comfort in each

of the three workshops of the Annex, which would bring

the total of men in the Great Collective Workshop to forty.

I do not know whether any good comparative figures are

available for this sort of count. Abbot Adalhard of Corbie,

whose monastery was considerably larger than that described

on the Plan of St. Gall, lists the following as the

regular contigent of laymen employed at Corbie:

twelve matricularii [odd jobbers selected from among the poor] and

thirty laymen. Of those: six at the first workshop, viz., three

shoemakers, two saddlers, one fuller. At the second workshop:

seventeen [Adalhard's arithmetic is wrong, the total of the individual

workmen listed for the second workshop is eighteen not seventeen],

viz., one at the supply room, six blacksmiths, two goldsmiths, two

shoemakers, two shieldmakers, one parchment maker, one polisher,

three carpenters. At the third workshop: three, viz., two porters at

the cellar and the dispensary, one at the infirmary. Two helpers,

viz., one at the place where the wood is stored in the bakehouse,

one at the middle gate, four carpenters, four masons, two physicians,

two at the vassals' lodge.[428]

If we subtract from this roll those laymen who on the Plan

of St. Gall are installed in other houses or have no special

space assigned to them (physicians, carpenters, masons,

and various others stationed at the Cellar, the Dispensary,

and the Infirmary), the remaining number of laymen is

twenty-one, including eleven who on the Plan of St. Gall

are installed in the Annex (blacksmiths, goldsmiths, and

metal founders).

It is hard to say whether such a comparison has any validity,

since Corbie, in addition to the craftsmen here listed,

had also no fewer than 150 prebends (adult oblates, who

received their daily sustenance in return for the performance

of some craft or service),[429]

many of whom may have

helped to supplement the work of the regular craftsmen.

In any case it appears to me safe to deduce from the layout

of the Great Collective Workshop that at the time of Louis

the Pious a crew of plus or minus forty

artifices (not counting

the coopers and wheelwrights installed in a separate

building) was considered to be the normal contingent of

craftsmen needed for the manufacture of the material requirements

of a monastic settlement, comprised of 250 to

270 souls.

[430]

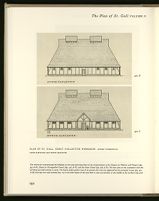

There is no question in my mind that the architect who

drew the plan of the Great Collective Workshop not only

had a clear idea of the number of men to be installed in this

structure and how they should be distributed throughout

the various workshops, but also was equally well informed

about the space requirements involved in each individual

craft, their functional interdependence, and the special

demands for lighting, heating, and fire protection, as we

shall see presently. As in all other buildings of this type,

there is good reason to assume that the walls that separated

the individual workshops from the center halls were not of

rigid construction, since the workmen in these outer spaces

depended on the two central fireplaces in the hall and the

two louvers in the roof above them for their warmth and

light. I should imagine that even the Workshop's interior

looked like a large open barn with barriers substantial

enough to give the workmen that autonomous feeling indispensable

to the performance of their skills, yet not so

obstructive as to preclude almost everyone's remaining in

sight of each other.

THE ANNEX

The crafts performed in the annex

The Annex (figs. 419 and 421) is as long as the main house,

but furnished with a single aisle along its southern side

and has a total depth of only 27½ feet. It is subdivided by

cross partitions into three equal spaces, which contain the

workshops of "goldsmiths" (aurifices), "blacksmiths"

(fabri feram̄torum), and "fullers" (fullones) and in the rear

along the outer wall "their bedrooms" (eorundem mansiunculae).

The annex has no separate entrance. It is accessible

through the main building, from which it is separated by a

courtyard 10 feet wide.

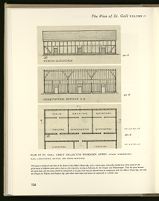

To put the workshops of the smiths and fullers under a

separate roof and segregate them from the other craftsmen

by an open court is an extremely sensible procedure. The

fullers need pits for lye and fuller's clay. And the work of

the smiths is associated with enervating noise and high intensity

fires. Their equipment is heavier and requires more

floor space than many of the other crafts. Hildemar lists as

the blacksmiths' tools, the "hammer" (malleus), the "anvil"

(incus), the "prongs" (forcipes), the "bellows" (follis), the

"turning wheel" (rota), the "grapple hook" (foscina), and

the "hearth" (focus),[431]

and tells us that with these they

manufacture "swords, lances, hoes, axes, and files."[432]

The

task of the fullers was to cleanse, shrink, and thicken clothes

by moisture, heat, and pressure. Their work was dependent

on access to open pits where the cloth could be soaked in

water mixed with detergents (fuller's clay) absorbing the

grease and oil of the cloth. There is no indication on the

Plan of St. Gall that this work was mechanized, unless the

fullers were permitted to use one of the water-powered

triphammers in the nearby Mortar House for this work.[433]

Absence of tailors and weavers

Attention must also be drawn to the absence of facilities

for tailors (sartores). This may suggest that the monks themselves

did the main work of cutting and tailoring clothes in

the large Vestiary that occupied the floor above the Refectory—a

conjecture that is corroborated by a remark in

Hildemar's commentary to the Rule of St. Benedict. It is

said there that the monks who are engaged in tailoring

clothes will have to disrupt their work instantly when the

bell for the divine service is struck, and must not even pull

the needle, awl, and thread (seta, literally "bristle" or

"bristly hair") out of the piece of cloth or leather on which

they are working.[434]

Lastly, it must be noted that the monastery has no

facilities for weaving. This is easily explained, because

weaving was historically a craft performed by women[435]

who,

of course, had no place in a monastic settlement for men.

Moreover, it is quite possible that most of the monks'

clothing was not woven, but produced by the process of

felting, i.e., the bringing together of masses of loose fibers

of wool under the combined influence of heat, moisture,

and friction until they became firmly interlocked in every

direction. This task, of course, could be performed by the

fullers.

It is an interesting commentary on the social and economic

structure of the period that it is within this primarily

industrial environment, composed of laymen and serfs, that

we also find the noble craftsmen, the goldsmiths, who furnished

the church with its sacred vessels and reliquaries

and the library with its precious jeweled covers for books.

The Great Collective Workshop is an impressive example

of industrial organization. Contracting into one establishment

practically all the services required for the community's

material survival, it reveals on the level of the service

building the same propensity for systematic architectural

integration which in the layout of the Church had led to a

combination of liturgical functions that had formerly been

distributed over separate sanctuaries.[436]

The same spirit had

produced an equally ingenious combination of functions in

the great architectural complex that encompasses the

Novitiate and the Infirmary.[437]