V. 9

OUTER SCHOOL & THE LODGING

OF THE SCHOOLMASTER

V.9.1

THE MONASTERY'S EDUCATIONAL

TASKS

ROYAL DIRECTIVES

Be it known, therefore, to your devotion pleasing to God, that we,

together with our faithful, have considered it to be useful that the

bishoprics and monasteries entrusted by the favor of Christ to our

control, in addition to the order of monastic life and the intercourse

of holy religion, in the culture of letters also ought to be zealous

in teaching those who by the gift of God are able to learn, according

to the capacity of each individual, so that just as the observance of

the rule imparts order and grace to honesty of morals, so also zeal

in teaching and learning may do the same for sentences, so that

those who desire to please God by living rightly should not neglect

Him also by speaking correctly.[346]

Thus wrote Charlemagne to Abbot Baugulf of Fulda in

a letter drafted by Alcuin, probably in 784 or 785. In a

second issue of the same letter, made out to Archbishop

Angilram of Metz, the emperor adds the admonition:

Do not neglect, therefore, if you wish to have our favor, to send

copies of this letter to all your suffragans and fellow bishops and to

all the monasteries.

The letter from which these sentences are quoted,

Charlemagne's famous epistola de litteris collendis,[347]

is one

of the first of a series of royal directives assigning to the

episcopal and monastic schools of the Frankish kingdom

an active role in education. It is one of the cornerstones of

that programmatic revival of both theological and classical

studies in which Charles took an intense personal interest

and which ushered in the Carolingian Renascence. One of

Charles's specific concerns was the intellectual formation of

the youth who were to form the core of the coming generation

of priests and clerics. In a great circular directive of

789, the admonitio generalis,[348]

he ruled that the children of

free laymen be admitted to the monastic schools, and that

reading classes be established for the young (scolae legentium

puerorum) in which the psalms, music, chant, the calendar

of the religious festivals, grammar, and the creeds of the

faith be taught.[349]

In the pursuit of these as well as the

more general aims of his educational reform, the emperor

systematically enlarged the body of his personal entourage

by adding to the old nucleus of administrative officers of

the Palace distinguished scholars from England, Ireland,

Italy, and Spain, thus setting up at the court itself a school

of learning that could be used as a model for the other

schools in his realm.[350]

The close relationship that existed between so many

medieval rulers and their leading bishops and abbots was

due in no small measure to friendships struck up between

these rulers and their former fellow students and teachers

during their education in monastic schools.[351]

Some monasteries

were understandably proud of these connections, as

may be gathered from a boastful passage in Hariulf's

Chronicle of St.-Riquier:

And as we are speaking of noblemen, never did anyone seek for

anything more distinguished, if he had knowledge of the nobility of

the monks of St.-Riquier: for in this monastery were educated

dukes, counts, the sons of dukes, and even the sons of kings. Every

higher dignitary, wherever located in the kingdom of the Franks,

boasted of having a relative in the abbey of St.-Riquier.[352]

STRESSES LEADING TO DIVISION INTO

INNER AND OUTER SCHOOLS

The stresses that these new educational obligations imposed

upon monastic seclusion were great and must have

been in debate at the second synod of Aachen which passed

the perplexing resolution, "There shall be no other school

in the monastery than that which is used for the instruction

of the future monks."[353]

I have already had occasion to point

out that it could not have been the intent of this ruling to

relieve the monasteries entirely from their share in the intellectual

training of the secular youth, which would have

been a complete reversal of the educational policies promoted

by Charlemagne. Rather it was the expression of a

conflict which in practice was settled by the division of the

monastic educational system into an "inner" and an "outer"

school, the former for the training of the future monks, the

latter for the instruction of those who planned to enter upon

the career of the secular clergy and of such laymen, poor

or noble, whose education was entrusted to monastic

teachers. The former was located in the cloister; the latter

outside it, at a place where it would not intrude on monastic

privacy. This is precisely the manner in which this problem

was settled on the Plan of St. Gall. The inner school is in

the cloister of the Novices,[354]

the Outer School lies between

the House for Distinguished Guests and the Abbot's House,

i.e., in a tract which in all other respects held a transitional

position between the monastic and secular world. Unlike

the schola interior, which remained essentially confined to

elementary learning, the schola exterior developed quickly

into a school for advanced study.[355]

DISTINGUISHED TEACHERS

In the ninth and tenth centuries in the monastery of St.

Gall, these schools produced some of the greatest teachers

of the period, the lives and works of whom Ekkehart IV

describes in his Casus sancti Galli with as much detail and

color as those of the greatest abbots.[356]

From Ekkehart's

account we also learn that the Outer School of the monastery

of St. Gall lay to the north of the Church, at almost

the same location it occupies on the Plan of St. Gall; for

in his description of the fire of 937 Ekkehart relates how the

dry shingles of the burning roof of the school were blown

by the north wind onto the church tower and ignited its

roof.[357]

V.9.2

THE OUTER SCHOOL

LAYOUT & MEANING OF EXPLANATORY TITLES

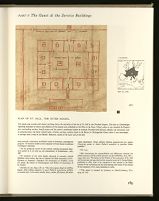

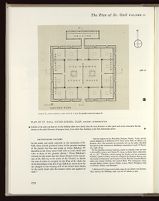

The Outer School of the Plan (fig. 407) is surrounded by a

fence which is designated with the hexameter:

Haec quoq. septa premunt, discentis uota iuuentae

These fences enclose the endeavor of the

learning youth

Measuring 70 feet in length and 55 feet in width, its surface

area exceeds that of the House for the Distinguished Guests

by a slight margin. The building consists of a large rectangular

hall, inscribed with the title domus communis

scolae id÷ uacationis. The interpretation of this title is

controversial. Keller, Willis, Campion, Leclercq, and Reinhardt

transcribed the abbreviation id÷ wrongly as idem

and interpreted the term uacatio as "recreation," thus translating

the line as "the common-room of the school and

place for recreation."[358]

Meier transcribed id÷ correctly as

id est[359]

and proposed uacatio is simply a Latinization of the

Greek word σχολή, which came into use in the Latin world

in republican times as the designation for higher studies in

literature, grammar and rhetoric.[360]

He interprets the title

accordingly as "the common hall for the school, i.e. the

place of study." The term uacatio is not used in the Rule

of St. Benedict, but to judge by the frequency with which

it appears in Hildemar's commentary to the Rule (written

around 845) it must have been fashionable in the Carolingian

period. Hildemar employs it no fewer than fifteen

times in a single chapter

[361]

and in one of these places pauses

to furnish his readers with a regular dictionary definition:

"

vacare means to relinquish one thing and to replace it

with some other preoccupation; it is in this sense that he

[St. Benedict] insists, in this chapter that, manual work

being set aside, the time thus released be used for study"

(`

Vacare'

est enim aliam rem relinquere et aliis insistere rebus,

sicuti in hoc loco relicta exercitatione manuum jubet insistere

lectioni).

[362]

In accordance with this definition I would translate

the title

domus communis scolae, id ÷ uacationis as "the

common hall for learning, i.e., for the time relinquished

from other obligations for the purpose of study."

[363]

The hall measures 30 feet by 40 feet and is divided in

half crosswise by a median wall. This partition does not run

clear across the room but has wide passages at either end,

suggesting that it was a low freestanding screen rather than

a massive wall and that the large hall, although each of the

two partitions is provided with its own fireplace and louver

(testu), was conceived of as a single space rather than as two

separate rooms. The fact that the inscription that defines

the purpose of this space runs across the wall partition corroborates

this interpretation.

Ranged peripherally around this center space are twelve

"small dwelling rooms for the students" (mansiunculae

scolasticorum hic),[364]

and in the area between them in the

middle of the southern long wall a slightly smaller space

which served as "entrance" (introitus). On the opposite

side a room of like dimensions served as "exit to the outhouse"

(necessarius exitus).

The rooms of the students each measure 12½ feet by 15

feet. They have in the center a small square, which Keller

and Willis interpreted as a table.[365]

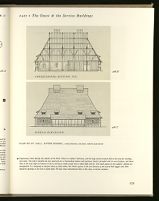

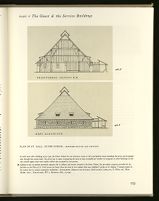

I am rather inclined to

think that these squares are the designation for dormer

windows in the lower slope of the roof, of the type shown

in the February representation of the Grimani Breviary

(fig. 367). The two louvers over the center space of the

house, although providing adequate lighting for the two

classrooms directly beneath them, would not have furnished

sufficient light for the pursuit of individual studies in the

student cubicles located in the aisles and lean-to's. Additional

light could, of course, also have been provided by

windows in the outer walls of the house, and with special

ease, if the latter were built in masonry. In our reconstruction

(figs. 408A-E) we have demonstrated both these

possibilities, introducing a volume of light that is probably

in excess of what one would reasonably expect to have been

available in the ninth century. Under no circumstances

should the squares in the students' rooms be interpreted

as fireplaces. Open fires in each of these twelve cubicles

would have constituted a fire hazard of the first degree and

would have been without parallel in any known or excavated

example of this construction type. Moreover, although

many of the students who occupied these rooms may well

have been of noble birth, their status as students was

scarcely of sufficient weight to entitle them to a privilege

otherwise accorded only to the highest ranking dignitaries

of the monastic community.[366]

All of the students' rooms are accessible from the main

hall. The doors are so arranged as to serve as entrance not

for one, but for two cubicles. The existence of these doors

and their carefully planned location leaves no doubt that

the students' rooms were separated from the main hall by

partitions. These partitions, however, could not have run

up to the roof of the house, as the cubicles depended for

their warmth on the open fires that burned in the main hall,

and this, in turn, presupposes a free exchange of air between

the main hall and the students' rooms.

NUMBER OF STUDENTS

The Plan gives no clues as to the number of students to

be housed in these rooms. Each mansiuncula might have

been reserved for a single student. But it could easily have

accommodated two; with less comfort, three. The total

number of students, accordingly, would either have been

twelve, twenty-four, or thirty-six. Since the privy of the

Outer School has fifteen toilet seats, the normal number of

students is likely to have exceeded the minimum number

of twelve.

We have already discussed at sufficient length the fact

that the Plan does not tell us where the students ate their

meals and where their food was cooked.

V.9.3

THE SCHOOLMASTER'S LODGING

The Master of the Outer School was not accommodated

in the school building itself, but in a special lodging built

against the northern aisle of the Church, immediately adjacent

to the school. It consists of two rooms, a "living

room" (mansio scolae) furnished with a corner fireplace, a

bench, and a table,[367]

and a "withdrawing" room (ejusdē

secretū), furnished with three beds (fig. 409).