VI.1.2

THE CHURCH

The dedicatory inscription of the Plan and the general

historical context in which it was made leave no doubt that

the Plan was drawn upon the request of Abbot Gozbert

(816-836) of St. Gall for the purpose of giving him guidance

in rebuilding his monastery.[4]

Gozbert began this

project in 830 by demolishing the church which Abbot

Otmar had built toward the middle of the preceding

century.[5]

The work on the new church proceeded so

rapidly that it could be dedicated in 837.[6]

Gozbert's church was gutted by fires in 937, 1314, and

1418 but the bulk of the walls, the clerestories of the nave

and their supporting arcades apparently were not signally

affected by these events.[7]

By contrast, the transept and the

choir were completely rebuilt by the Abbots Eglolf and

Ulrich VIII, from 1439-83.[8]

It is in the form it had then

attained that the church is portrayed on the oldest bird's-eye

views of the city: in a woodcut dated 1545 by Heinrich

Vogtherr, in an etching on iron by Melchior Frank, dated

1596 (fig. 507), in an engraving of essentially the same

view by Matthaeus Merian, published in 1638 (fig. 509X),

as well as in several other drawings, the most important of

which are a pen drawing of 1666 and a large drawing on

parchment of 1671.[9]

In 1712 the abbey was ransacked by the Protestants and

the monks were expelled.[10]

When they returned a few

years later it was painfully clear that extensive restorations

would have to be undertaken. In anticipation of that event

some detailed architectural surveys were made. In 1717

architect Johannes Caspar Glattburger surveyed the church

and recorded its dimensions.[11]

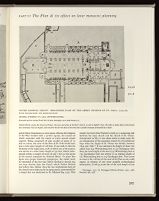

Two years later Pater Gabriel

Hecht made a scale-drawn plan of the entire monastery

site, dated September 17, 1719 (fig. 510). In 1725-26 he

added to this a set of no less than fourteen architectural

drawings, in which he set forth how he thought the damaged

church and other monastic buildings should be renovated.[12]

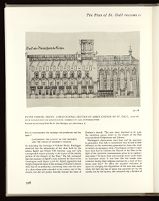

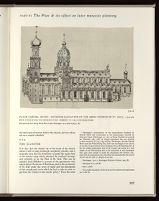

Three of these drawings, reproduced in figures 511A-C,

render the condition of the still surviving parts of the

medieval church with great precision and show that what

Hecht had in mind was not so much a reconstruction as a

superficial modernization of the then existing work. Hecht

proposed that the gothic choir be retained in its entirety.

He added some baroque touches in surface treatment by

superimposing a new columnar order upon the exterior

elevation of the choir. In the interior he modernized the

Gothic supports but otherwise retained the structure as he

found it, leaving its Gothic vaults and windows wholly

untouched. In the nave, likewise, he does not appear to

have undertaken any radical changes. Hardegger is convinced

that the arcades and the superincumbent clerestories

of the nave which Hecht had before his eyes as he made his

drawings were in essence still those of Abbot Gozbert's

church (compare fig. 511A and B with fig. 512B and C).

He feels that Hecht proposed to retain the intercolumniation

of Gozbert's church and confined himself to simply

increasing the heights in this part of the building. The only

truly new feature in his proposal was the conversion of the

two nave bays lying next to the choir into a pseudotransept

surmounted by a dome, and the introduction on each of

the two long sides of the church of a continuous system of

chapels. For the rest he confined himself to superimposing

upon the existing work a decorative relief of surface

features, designed in the prevailing taste of the period.

This included in the the interior the complete encasing of

Gozbert's arcade columns in baroque shaped piers.

Although Hecht's design proposals had no effect on the

actual course of events, which took a radical turn a quarter

of a century later, they are of incomparable historical

value because they embody with amazing accuracy the

record of what was then still left, or could then be discerned,

of Gozbert's church. In analyzing this material, Hardegger

came to the following conclusions concerning Gozbert's

church and its relation to the Plan of St. Gall:

1. As stipulated in the explanatory legends of the Plan

of St. Gall, Abbot Gozbert assigned to the nave of his

church a width of 40 feet and to each of his aisles a width

of 20 feet—dimensions which also are in conformity with

the manner in which the Church is drawn on the Plan.

2. In full compliance with the intercolumnar titles of

the Plan, but in deviation from the drawing (in which the

columns are spaced at intervals of 20 feet) he assigns to the

arcades an intercolumnar span of 12 feet.

3. In full compliance with the great axial title of the

Church of the Plan, but again in deviation from the

drawing (where the church is shown to have a length of

more than 300 feet) he reduced the length of the church to

200 feet. He attained this goal by drastic changes in the

design of the nave of the church, but retained the layout of

transept and choir virtually in the form in which it was

shown on the Plan.

Hardegger's supporting evidence for these conclusions is

presented below.

CONCERNING THE WIDTH AND THE LENGTH

OF GOZBERT'S CHURCH

According to the scale-drawn plan made by Father Gabriel

Hecht, in 1725-26 the nave of the medieval church had a

length of 155 feet. Its clear inner width was 46 feet, that of

the aisles 23 feet. The two clerestories rested on sixteen

piers, each 3 feet square. They were placed at intervals of

17 feet (measured on center) and had between them a clear

arcade span of 14 feet.[13]

Hardegger could establish that

Gabriel Hecht, in measuring the medieval building as well

as in laying out his own drawings availed himself of the

so-called Württemberg foot[14]

which had a unit value of

28.6 cm., and consequently was considerably smaller than

the foot used in drafting the Plan of St. Gall. Hardegger

thought that the architect who drew the Plan of St. Gall

scaled his layout with a foot that formed an equivalent of

33.3 cm.[15]

Converted to this scale, the measurements

recorded by Gabriel Hecht would read as follows: length

of nave: 133 feet; clear width of nave: 40 feet; clear width

of aisles: 20 feet; clear span of the arcade openings: 12 feet.

This in complete harmony with the dimensions stipulated

in the explanatory titles of the Plan of St. Gall, with one

difference only: the builders of Gozbert's church interpreted

these dimensions as clear spans, whereas the designer

of the Plan worked with a 40-foot square, the corners of

which coincided with the center of every second arcade

support. Being composed of nine arcades of spans of 12

feet on center, the nave of the Plan of St. Gall would have

had a clear inner length of 108 feet. If one adds to this the

thickness of the eight piers, each of which was 3 feet square,

one arrives at a clear inner length of 132 feet, which corresponds

within a margin of error of only 1 foot to the layout

of the church measured by Gabriel Hecht. To place this

figure into proper historical perspective, the reader must

be reminded of the fact that Abbot Gozbert's church was

two bays shorter than the church which Father Gabriel

had before him. Before 1623 the two westernmost bays of

the church were taken up by an open porch, surmounted by

a chapel that was dedicated to St. Michael (fig. 513). This

chapel was built after Gozbert's death as a connecting link

between the main church and the church of St. Otmar.

Consecrated in 867, it was taken down to make room for

an enlargement of the monastery church by two additional

bays when the chapel of St. Otmar was rebuilt, between

1623 and 1626.

[16]

If one subtracts the length of these two

added bays (34 Württemberg feet or 23 Carolingian feet)

from the total length of the nave (155 Württemberg feet or

133 Carolingian feet) one arrives at an original length of

121 Württemberg feet or 105 Carolingian feet. This comes

as close to the 108 feet of the nave of the Plan as one could

expect, in absence of any more tangible archaeological

information. It left 95 more feet of the total length of 200

feet to accommodate the transept, the presbytery and the

apse.

[17]

CONCERNING THE LAYOUT OF THE TRANSEPT

AND THE CHOIR OF GOZBERT'S CHURCH

In examining the drawings of Gabriel Hecht, Hardegger

observed that the dimensions of the choir built by the

abbots Eglolf and Ulrich VIII between 1439 and 1483

corresponded almost precisely to the layout of the eastern

portion of the Church of the Plan.[18]

He felt convinced

that the masonry of Eglolf's choir followed the lines of the

Carolingian work (figure 512A-C). Eglolf apparently had

simply merged the space of the crossing of Gozbert's church

with that of its presbytery, converting them into the nave

of a choir whose aisles extended to the eastern end of the

church, but did not project laterally beyond the body of

Gozbert's church. The new choir absorbed in its mass

the subsidiary spaces which in the church of the Plan

accommodated Scriptorium and Library.

Hardegger's observations were keen and his argument

is persuasive. One fails to understand why he had so little

influence on the controversy generated by those who tried

to resolve, in retrospect, what a Carolingian architect might

have done had he redrawn the Church of the Plan in the

light of the corrective measurements given in its explanatory

titles.[19]

To leave choir and transept intact made sense

in functional terms: it was here that the monks were

stationed during their religious services for a total of four

hours each day.[20]

To effect the required reduction of

space by changing the dispositions of the nave also made

sense, for here the loss of space was incurred not by the

monks, but by the laymen, who attended only a fraction of

the total cycle of services held in the church, and even those

not on a regular schedule.