The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V.1.1.. |

| V.1.2. |

| V.1.3. |

| V.1.4. |

| V. 2. |

| V.2.1. |

| 10. |

| 10. |

| V.2.2. |

YEAVERING, NORTHUMBRIA, AND CHEDDAR,

SOMERSET, ENGLAND |

| V. 3. |

| V.3.1. |

| V.3.2. |

| V.3.3. |

| V. 4. |

| V.4.1. |

| V.4.2. |

| V.4.3. |

| V. 5. |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

| V. 6. |

| V.6.1. |

| V.6.2. |

| V.6.3. |

| V.6.4. |

| V. 7. |

| V.7.1. |

| V.7.2. |

| V.7.3. |

| V.7.4. |

| V.7.5. |

| V.7.6. |

| V. 8. |

| V.8.1. |

| V.8.2. |

| V.8.3. |

| V.8.4. |

| V.8.5. |

| V.8.6. |

| V.8.7. |

| V.8.8. |

| V. 9. |

| V.9.1. |

| V.9.2. |

| V.9.3. |

| V. 10. |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. |

| V. 11. |

| V.11.1. |

| V.11.2. |

| V.11.3. |

| V. 12. |

| V.12.1. |

| V.12.2. |

| V.12.3. |

| V. 13. |

| V.13.1. |

| V.13.2. |

| V. 14. |

| V.14.1. |

| V.14.2. |

| V. 15. |

| V.15.1. |

| V.15.2. |

| V.15.3. |

| V.15.4. |

| V. 16. |

| V.16.1. |

| V.16.2. |

| V.16.3. |

| V.16.4. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| V.18.1. |

| V.18.2. |

| V.18.3. |

| V.18.4. |

| V.18.5. |

| VI. |

| VI. 1. |

| VI.I.I. |

| VI.1.2. |

| VI.1.3. |

| VI.1.4. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI.2.1. |

| VI.2.2. |

| VI.2.3. |

| VI.2.4. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI.3.1. |

| VI.3.2. |

| VI.3.3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI.4.1. |

| VI.4.2. |

| VI.4.3. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

YEAVERING, NORTHUMBRIA, AND CHEDDAR,

SOMERSET, ENGLAND

Until the summer of 1956, England, peculiarly enough, had

not yielded a single house site comparable to any of the

Continental finds. A small settlement, of aisled post-and-wattle

houses excavated in 1946 by Gerhard Bersu on a

promontory of the shore of Ramsay Bay on the Isle of

Man,[152]

was probably not an Anglo-Saxon settlement but

an outpost of a Norse raiding party which was occupied

only intermittently. In the summer of 1956, however,

Brian Hope-Taylor came upon the site of a royal Anglo-Saxon

palace of the seventh century at Old Yeavering in

Northumbria (Bede's villa regalis ad Gefrin),[153]

which contained

the remains of no fewer than twenty-five timbered

houses, most of them aisled; and in 1960-62 Philip Rahtz

WARENDORF, WESTPHALIA, GERMANY

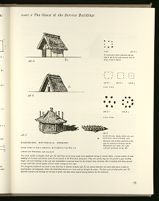

325.A EXTERIOR VIEW REDRAWN FROM WINKELMANN

325.A.1 PLAN. HOUSE 47, LEVEL A, PERIOD 4

HOUSE TYPES OF EARLY MEDIEVAL SETTLEMENTS. 650-800 A.D.

[after Winkelmann, 1958, 500, fig. 5]

Excavations conducted in 1951 by Wilhelm Winkelmann in Warendorf, on the south side of the Ems, brought to light traces and remains in the

soil of no fewer than 186 separate buildings, which could be accurately dated by pottery and other associated artifacts. The settlement was

rebuilt four or five times, in most cases—as the remains of charcoal and fired clay found in many postholes indicate—after houses of the previous

settlement had been destroyed by fire.

Analysis of the successive stages of the site disclosed that each inhabited level consisted of a group of four to five farmyards occupying an area

of about 984 feet (100m) square. Each farmyard held a large dwelling, and fourteen to fifteen smaller auxiliary buildings (barns, stables, sheds,

weaving houses). The variety of these service structures is shown in figs. 326.A-F.

The reason for the boat shape of House 47, a feature very common in early Scandinavian architecture, is obscure. For other examples of

longhouses of this type see below, V. 17. 3.

WARENDORF, WESTPHALIA, GERMANY

325.B EXTERIOR VIEW REDRAWN FROM WINKELMANN

Arrow indicates general direction from which exterior view above is taken

325.B.1 PLAN. HOUSE 7, LEVEL A, PERIOD 1

HOUSE TYPES OF EARLY MEDIEVAL SETTLEMENTS, 650-800 A.D.

[after Winkelmann, 1958, 504, fig. 8]

Plans and reconstructions on these pages are typical of the man or principal dwellings of the Warendorf settlements. By virtue of both size and

architectural distinction, as well as the presence of a hearth, they are unquestionably the dwellings of the owners of the land. They were boat-shaped

(fig. 325.A) or of rectangular plan, as above, varying in length between 45 and 95 feet (14-29m), in width between 14½ and 32 feet

(4.5-7.0m). Their roofs were supported by a perimeter of heavy posts set vertically into the ground, each buttressed from outside by a second,

lighter post rising at an angle to meet the inner post near its head. The triangulation counteracted the thrust of the roof. Wall panels between

vertical posts were daubed with clay.

The axes of these dwellings, and most of the subsidiary structures, ran from west to east. This feature, characteristic of many pre- and

protohistoric buildings in these latitudes, was apparently determined by the desire to expose only a gable wall to the prevailing (here, western)

winds. The houses were entered on their long walls through two opposing entrances in midwall, each protected by a porch. The hearth lay in the

eastern half of the house.

WARENDORF, WESTPHALIA, GERMANY

326.A

326.B

326.C

HOUSE TYPES OF EARLY MEDIEVAL SETTLEMENTS, 650-800 A.D.

[redrawn after Winkelmann, 1958, 504, fig. 8]

These pages give a visual account of the variety of service structures that one might have expected to find in the farmyards of Warendorf.

They have been redrawn from models made under the direction of Wilhelm Winkelmann, and are on display at the Museum für Vor- und

Frühgeschichte, Münster, under the aegis of which the excavations at Warendorf were conducted.

There were forty service buildings of rectangular plan with vertically boarded walls at Warendorf (326.A), used as barns and stables. Small

houses with hearths built in the manner of the larger dwellings presumably provided housing for serfs (326.C). Numerous small sheds with open

walls (326.B) were probably utility buildings for various kinds of storage.

WARENDORF, WESTPHALIA, GERMANY

326.D

326.E

326.F

HOUSE TYPES OF EARLY MEDIEVAL SETTLEMENTS, 650-800 A.D.

[redrawn after Winkelmann, 1958, 504, fig. 8]

The small, walled rectangular shed (326.D) could have served many needs from implement storage to animal shelter. A great number of small

buildings of A-frame construction (326.E) were found in the Warendorf farmyards. They were partly dug into the ground to gain standing

height, and some buildings of this type were identifiable as weaving houses by the artifacts they contained. But a building with below-ground

storage could have served equally well for winter storage of root crops.

The polygonal framework was used to store loose hay or sheaves of grain (326.F); its conical thatched roof could slide down its poles to

accommodate and adequately shelter the diminishing harvest as it was used up through the winter. The floor grid of lashed poles (326.X)

afforded aeration and drainage for the hay or grain; the plans show typical posting patterns for the structures.

326.X HAYSTACK SHELTER, left, and

DRYING PLATFORM, right

Haystacks and aeration platforms of this

type are common in Germany and the

Netherlands even today. For a fine

15th-cent. portrayal, see fig. 368.

326.G WARENDORF, WESTPHALIA, GERMANY

HOUSE TYPES OF EARLY MEDIEVAL SETTLEMENT, 650-800 A.D.

[redrawn from Winkelmann, 1958, 500, 504]

Each of the buildings shown on this and the preceding pages is referred to in the Alamannic, Bajuvarian, and Salic laws discussed above

(p. 26ff), where they are designated in the following manner:

The house of a free man = DOMUS or SALA LIBERI (figs. 325A-B); the house of a serf = DOMUS SERVI (fig. 326.C); a wall-enclosed

barn = SCORIA (fig. 326.A); an unenclosed barn = SCOF (fig. 326.B); a granary = PARC (fig. 326.D); a haystack, or stacked sheaves of

wheat = MITA (fig. 326.F). For a more complete account and the etymology of these terms see above, p. 29, notes 14-18, and the chart in

Winkelmann, 1954, 210, fig. 12.

(sedes regalis aet Ceodre) with the remains of a timbered

long hall from the time of King Alfred (871-900)[155] and an

aisled hall, likewise in timber, from the reign of Henry I

(1100-35), a plan of which is reproduced in figure 324. The

results of these excavations once fully published will put

an end to another enigmatic chapter of early medieval

house research.

On Yeavering, unfortunately ten years after the excavation not

even a preliminary report is available. Brief notices will be found in

Wilson, 1957, 148-49, and Colvin, 1963, 2-3 and 5-6.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||