The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V.1.1.. |

| V.1.2. |

| V.1.3. |

| V.1.4. |

| V. 2. |

| V.2.1. |

| 10. |

| 10. |

| V.2.2. |

| V. 3. |

| V.3.1. |

| V.3.2. |

| V.3.3. |

| V. 4. |

| V.4.1. |

| V.4.2. |

| V.4.3. |

| V. 5. |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

| V. 6. |

| V.6.1. |

| V.6.2. |

| V.6.3. |

| V.6.4. |

| V. 7. |

| V.7.1. |

| V.7.2. |

| V.7.3. |

| V.7.4. |

| V.7.5. |

| V.7.6. |

| V. 8. |

| V.8.1. |

| V.8.2. |

| V.8.3. |

| V.8.4. |

| V.8.5. |

| V.8.6. |

| V.8.7. |

| V.8.8. |

| V. 9. |

| V.9.1. |

| V.9.2. |

| V.9.3. |

| V. 10. |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. |

| V. 11. |

| V.11.1. |

| V.11.2. |

| V.11.3. |

| V. 12. |

| V.12.1. |

| V.12.2. |

| V.12.3. |

| V. 13. |

| V.13.1. |

| V.13.2. |

| V. 14. |

| V.14.1. |

| V.14.2. |

| V. 15. |

| V.15.1. |

| V.15.2. |

| V.15.3. |

| V.15.4. |

| V. 16. |

| V.16.1. |

| V.16.2. |

| V.16.3. |

| V.16.4. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| V.18.1. |

| V.18.2. |

| V.18.3. |

| V.18.4. |

| V.18.5. |

| VI. |

| VI. 1. | VI. 1 |

| VI.I.I. |

| VI.1.2. |

| VI.1.3. |

| VI.1.4. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI.2.1. |

| VI.2.2. |

| VI.2.3. |

| VI.2.4. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI.3.1. |

| VI.3.2. |

| VI.3.3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI.4.1. |

| VI.4.2. |

| VI.4.3. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

VI. 1

REBUILDING OF THE

MONASTERY OF ST. GALL BY

ABBOT GOZBERT & HIS

SUCCESSORS

FROM A.D. 830 ONWARD

VI.I.I

HARDEGGER'S CONTRIBUTION

Up to the middle of the eighteenth century, the church

which Abbot Gozbert built between 830 and 837 was still

essentially intact, except for its transept and choir. From

1755 onwards, however, not only the church itself but

most of the conventual buildings as well were torn

down to make room for the magnificent and stately rococo

buildings that form the pride of modern St. Gall (figs. 505

and 506). The street pattern and the alignment of the

houses that cluster around the abbey retain with astonishing

precision the shape of the original site, but of the Carolingian

buildings that once rose on this precinct not a single

stone appears to be left above ground level. A satisfactory

answer to the question of whether, or to what extent,

Abbot Gozbert and his successors adhered to the Plan of

St. Gall as they rebuilt the monastery could only be found

through a systematic program of excavations, for which at

present there does not appear to exist a glimmer of hope.[1]

If we are nevertheless not entirely ignorant about Gozbert's

work, this is due to the existence of a precious set of

architectural drawings made early in the eighteenth century

when much of the Carolingian work was still discernible.

These late drawings have been brilliantly analyzed by

August Hardegger, first in a dissertation published in

1917,[2]

and a few years later in a volume of the Baudenkmäler

der Stadt St. Gallen, which Hardegger wrote in

cooperation with architect Salomon Schlatter and Traugott

Schiess.[3]

It is to the imaginative, yet sober and cautious

reasoning displayed in these studies, that we owe whatever

tangible knowledge can be gleaned from the available

sources about the design and layout of the monastery

rebuilt by Abbot Gozbert and his successors.

For a peremptory review of excavations undertaken in 1964 in

connection with the installation of a new heating system in the 18thcentury

church see Sennhauser, 1965. A full report by Sennhauser on

these findings is pending.

VI.1.2

THE CHURCH

The dedicatory inscription of the Plan and the general

historical context in which it was made leave no doubt that

the Plan was drawn upon the request of Abbot Gozbert

(816-836) of St. Gall for the purpose of giving him guidance

in rebuilding his monastery.[4]

Gozbert began this

project in 830 by demolishing the church which Abbot

Otmar had built toward the middle of the preceding

century.[5]

The work on the new church proceeded so

rapidly that it could be dedicated in 837.[6]

Gozbert's church was gutted by fires in 937, 1314, and

1418 but the bulk of the walls, the clerestories of the nave

and their supporting arcades apparently were not signally

affected by these events.[7]

By contrast, the transept and the

choir were completely rebuilt by the Abbots Eglolf and

Ulrich VIII, from 1439-83.[8]

It is in the form it had then

attained that the church is portrayed on the oldest bird's-eye

views of the city: in a woodcut dated 1545 by Heinrich

Vogtherr, in an etching on iron by Melchior Frank, dated

1596 (fig. 507), in an engraving of essentially the same

view by Matthaeus Merian, published in 1638 (fig. 509X),

as well as in several other drawings, the most important of

which are a pen drawing of 1666 and a large drawing on

parchment of 1671.[9]

In 1712 the abbey was ransacked by the Protestants and

the monks were expelled.[10]

When they returned a few

years later it was painfully clear that extensive restorations

would have to be undertaken. In anticipation of that event

some detailed architectural surveys were made. In 1717

architect Johannes Caspar Glattburger surveyed the church

and recorded its dimensions.[11]

Two years later Pater Gabriel

Hecht made a scale-drawn plan of the entire monastery

site, dated September 17, 1719 (fig. 510). In 1725-26 he

added to this a set of no less than fourteen architectural

drawings, in which he set forth how he thought the damaged

church and other monastic buildings should be renovated.[12]

508. ST. GALL. ABBEY AS IT APPEARED ABOUT 1642. BIRD'S-EYE VIEW FROM THE EAST

DETAIL OF A MODEL OF THE CITY OF ST. GALL

ST. GALL, HISTORISCHES MUSEUM [photo: Horn]

render the condition of the still surviving parts of the

medieval church with great precision and show that what

Hecht had in mind was not so much a reconstruction as a

superficial modernization of the then existing work. Hecht

proposed that the gothic choir be retained in its entirety.

He added some baroque touches in surface treatment by

superimposing a new columnar order upon the exterior

elevation of the choir. In the interior he modernized the

Gothic supports but otherwise retained the structure as he

found it, leaving its Gothic vaults and windows wholly

untouched. In the nave, likewise, he does not appear to

have undertaken any radical changes. Hardegger is convinced

that the arcades and the superincumbent clerestories

of the nave which Hecht had before his eyes as he made his

drawings were in essence still those of Abbot Gozbert's

church (compare fig. 511A and B with fig. 512B and C).

He feels that Hecht proposed to retain the intercolumniation

of Gozbert's church and confined himself to simply

increasing the heights in this part of the building. The only

truly new feature in his proposal was the conversion of the

two nave bays lying next to the choir into a pseudotransept

surmounted by a dome, and the introduction on each of

the two long sides of the church of a continuous system of

chapels. For the rest he confined himself to superimposing

upon the existing work a decorative relief of surface

features, designed in the prevailing taste of the period.

This included in the the interior the complete encasing of

Gozbert's arcade columns in baroque shaped piers.

Although Hecht's design proposals had no effect on the

actual course of events, which took a radical turn a quarter

of a century later, they are of incomparable historical

value because they embody with amazing accuracy the

record of what was then still left, or could then be discerned,

of Gozbert's church. In analyzing this material, Hardegger

came to the following conclusions concerning Gozbert's

church and its relation to the Plan of St. Gall:

1. As stipulated in the explanatory legends of the Plan

of St. Gall, Abbot Gozbert assigned to the nave of his

church a width of 40 feet and to each of his aisles a width

of 20 feet—dimensions which also are in conformity with

the manner in which the Church is drawn on the Plan.

2. In full compliance with the intercolumnar titles of

the Plan, but in deviation from the drawing (in which the

509. ST. GALL. ABBEY AS IT APPEARED ABOUT 1642. BIRD'S EYE VIEW FROM THE SOUTHEAST

DETAIL OF A MODEL OF THE CITY OF ST. GALL

ST. GALL HISTORISCHES MUSEUM [photo: Horn]

arcades an intercolumnar span of 12 feet.

3. In full compliance with the great axial title of the

Church of the Plan, but again in deviation from the

drawing (where the church is shown to have a length of

more than 300 feet) he reduced the length of the church to

200 feet. He attained this goal by drastic changes in the

design of the nave of the church, but retained the layout of

transept and choir virtually in the form in which it was

shown on the Plan.

Hardegger's supporting evidence for these conclusions is

presented below.

CONCERNING THE WIDTH AND THE LENGTH

OF GOZBERT'S CHURCH

According to the scale-drawn plan made by Father Gabriel

Hecht, in 1725-26 the nave of the medieval church had a

length of 155 feet. Its clear inner width was 46 feet, that of

the aisles 23 feet. The two clerestories rested on sixteen

piers, each 3 feet square. They were placed at intervals of

17 feet (measured on center) and had between them a clear

arcade span of 14 feet.[13]

Hardegger could establish that

Gabriel Hecht, in measuring the medieval building as well

as in laying out his own drawings availed himself of the

so-called Württemberg foot[14]

which had a unit value of

28.6 cm., and consequently was considerably smaller than

the foot used in drafting the Plan of St. Gall. Hardegger

thought that the architect who drew the Plan of St. Gall

scaled his layout with a foot that formed an equivalent of

33.3 cm.[15]

Converted to this scale, the measurements

recorded by Gabriel Hecht would read as follows: length

of nave: 133 feet; clear width of nave: 40 feet; clear width

of aisles: 20 feet; clear span of the arcade openings: 12 feet.

This in complete harmony with the dimensions stipulated

in the explanatory titles of the Plan of St. Gall, with one

difference only: the builders of Gozbert's church interpreted

509.X MATTHAEUS MERIAN. ABBEY AND CITY OF ST. GALL. BIRD'S-EYE VIEW FROM THE EAST

ETCHING: 20.7 × 31.2cm. FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1638 & BASED ON THE MELCHIOR FRANK ETCHING, FIG. 507

Merian's etching defines with great clarity the tripartite division of the post-medieval city; the abbey, the upper, and the lower town all

separated from one another by high girdle walls. The city by now had grown to more than six times the ground area of the monastery in the

shadow of which it had arisen. The wedge-shaped boundaries of the rise of land on which the monastery was built are distinctive. (For

identification of the parts of the Church with its staggered roof levels, see caption to fig. 513.)

Noteworthy among the medieval buildings east of the Church are: the circular chapel of St. Gallus (built 958-971) and north of it St. Peter's

chapel, the oldest sanctuary on the grounds and dating from before the incumbency of Abbot Gozbert. East of it and in axial prolongation lies

St. Catherine's chapel, where the monk Tutilo was buried in 912, and that served as chapel for the abbot's palace. (The latter, a tall building

north of St. Catherine's, is not identical with the PALATIUM built by Grimoald, abbot from 841-872, and gutted by fire in 1418; it may have

been located further west.

509.Y JOHANNES ZUBER, CADASTRAL PLAN

OF THE CITY OF ST. GALL & ENVIRONS, 1835.

[scale of figure 509.Y as shown, about 1:11,500]

ST. GALL, STADTBIBLIOTHEK, CH 9000. SIZE OF ORIGINAL: 53 × 746m

[By courtesy of the Stadtbibliothek]

The plan carries the title GRUNDRISS DER STADT ST. GALLEN NEBST DER

UMGEBUNG AUFGENOMMEN VON

JOH. ZUBER. LITHOGRAPHIE VON HELM UND SOHN, ST. GALLEN, 1835.

509.Z DETAIL Central portion of St. Gall with the cathedral (shown at about 1:11,500)

source: STADT S. GALLEN, 1964, 1:5000 Art Institut Orell Füssli AG Zurich, 1964

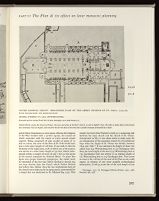

510. PATER GABRIEL HECHT. "ICHNOGRAPHIA"

MEASURED PLAN OF THE MONASTERY OF ST. GALL DATED A.D. SEPTEMBER 1719 ST. GALL, STIFTSARCHIV

KARTEN UND PLÄNE, M.83

[By courtesy of the Stiftsarchiv]

The disposition of church and cloister are basically the same as those shown on the etching of Melchior Frank (fig. 507), except that the church

was enlarged westward in 1623-26 by two bays that absorbed the space formerly occupied by St. Michael's chapel. All of the smaller chapels to

the east of the Church (St. Gall, Holy Sepulchre, St. Peter's, St. Catherine's) were demolished during a building campaign undertaken by

Abbot Gallus II Alt in 1666-1671. He erected a long wing of domestic facilities east of the church (nos. 18-25) including a new dining room

and audience hall for the abbot (no. 18) and a new chapel for St. Gall (no. 19), new lodgings for the porter (no. 20) and beyond the passage

beneath the porter's lodging, servants' quarters, a bakery, and a pharmacy (nos. 21-25). The old but decaying abbot's palace remained at its

original site (no. 48) but the site of St. Peter's and St. Catherine's was now occupied by a carriage house (no. 32).

511.A PATER GABRIEL HECHT. MEASURED PLAN OF THE ABBEY CHURCH OF ST. GALL, 1725-26,

WITH SUGGESTIONS FOR MODIFICATION

ORIGINAL FORMERLY ST. GALL STIFTSBIBLIOTHEK,

Evacuated and lost during World War II [after Hardegger, 1917, plate facing p. 4]

Gabriel Hecht retains the church of Otmar, the nave and aisles of Gozbert's church, as well as Eglolf's choir. He adds on either flank of the church

two continuous rows of chapels, and converts the last two bays of the nave into a pseudo-transept surmounted by a tower.

of the Plan worked with a 40-foot square, the corners of

which coincided with the center of every second arcade

support. Being composed of nine arcades of spans of 12

feet on center, the nave of the Plan of St. Gall would have

had a clear inner length of 108 feet. If one adds to this the

thickness of the eight piers, each of which was 3 feet square,

one arrives at a clear inner length of 132 feet, which corresponds

within a margin of error of only 1 foot to the layout

of the church measured by Gabriel Hecht. To place this

figure into proper historical perspective, the reader must

be reminded of the fact that Abbot Gozbert's church was

two bays shorter than the church which Father Gabriel

had before him. Before 1623 the two westernmost bays of

the church were taken up by an open porch, surmounted by

a chapel that was dedicated to St. Michael (fig. 513). This

chapel was built after Gozbert's death as a connecting link

between the main church and the church of St. Otmar.

Consecrated in 867, it was taken down to make room for

an enlargement of the monastery church by two additional

bays when the chapel of St. Otmar was rebuilt, between

1623 and 1626.[16] If one subtracts the length of these two

added bays (34 Württemberg feet or 23 Carolingian feet)

from the total length of the nave (155 Württemberg feet or

133 Carolingian feet) one arrives at an original length of

121 Württemberg feet or 105 Carolingian feet. This comes

as close to the 108 feet of the nave of the Plan as one could

expect, in absence of any more tangible archaeological

information. It left 95 more feet of the total length of 200

511.B PATER GABRIEL HECHT. LONGITUDINAL SECTION OF ABBEY CHURCH OF ST. GALL, 1725-26,

WITH SUGGESTIONS FOR MODIFICATION. FORMERLY ST. GALL STIFTSBIBLIOTHEK

Evacuated and lost during World War II [after Hardegger, 1917, plate facing p. 5]

apse.[17]

Hardegger, 1917, 47; Poeschel, 1961, 31 accepts this interpretation

of the scale of the Plan. Hardegger's assumption was confirmed by our

own calculations (cf. I, 95-97).

Hardegger's interpretation of the measurements furnished by

Gabriel Hecht find confirmation in the measurements recorded by

Johannes Caspar Glattburger, in 1917, as Erwin Poeschel has pointed

out (Poeschel, 1961, 30ff). As already mentioned, they are, recorded

in Acta monasterii, B. 322 p. 839 and 841. Glattburger, who like Gabriel

Hecht used the Württemberg foot, listed the total length of the church

as 272 feet. If one subtracts from this figure the 34 Württemberg feet of

the two added westernmost bays of the church, one arrives at a total

length of 238 Württemberg feet or the equivalent of 206 Carolingian

feet, again close enough to justify the assumption that Gozbert complied

with the explanatory title of the Plan that stipulated that the church

should only be built to a length of 200 feet.

CONCERNING THE LAYOUT OF THE TRANSEPT

AND THE CHOIR OF GOZBERT'S CHURCH

In examining the drawings of Gabriel Hecht, Hardegger

observed that the dimensions of the choir built by the

abbots Eglolf and Ulrich VIII between 1439 and 1483

corresponded almost precisely to the layout of the eastern

portion of the Church of the Plan.[18]

He felt convinced

that the masonry of Eglolf's choir followed the lines of the

Carolingian work (figure 512A-C). Eglolf apparently had

simply merged the space of the crossing of Gozbert's church

with that of its presbytery, converting them into the nave

of a choir whose aisles extended to the eastern end of the

church, but did not project laterally beyond the body of

Gozbert's church. The new choir absorbed in its mass

the subsidiary spaces which in the church of the Plan

accommodated Scriptorium and Library.

Hardegger's observations were keen and his argument

is persuasive. One fails to understand why he had so little

influence on the controversy generated by those who tried

to resolve, in retrospect, what a Carolingian architect might

have done had he redrawn the Church of the Plan in the

light of the corrective measurements given in its explanatory

titles.[19]

To leave choir and transept intact made sense

in functional terms: it was here that the monks were

stationed during their religious services for a total of four

hours each day.[20]

To effect the required reduction of

space by changing the dispositions of the nave also made

sense, for here the loss of space was incurred not by the

monks, but by the laymen, who attended only a fraction of

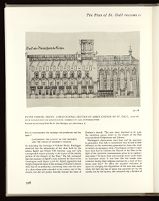

511.C PATER GABRIEL HECHT. EXTERIOR ELEVATION OF THE ABBEY CHURCH OF ST. GALL, 1725-26,

WITH SUGGESTIONS FOR MODIFICATION. FORMERLY ST. GALL STIFTSBIBLIOTHEK

Evacuated and lost during World War II [after Hardegger, 1917, plate facing p. 18]

not on a regular schedule.

Otmar, a man of noble Alemannic birth, raised in the episcopal city

of Chur in Raetia, became abbot of the monastery of St. Gall in 719

and died in exile on the island of Werd in the Rhine River in 759. For

these and other bibliographical details and sources see Duft, 1959, 17.

The most recent review of what is known about Otmar's Church is in

Poeschel, 1961, 7-9.

See Poeschel, 1961, 41ff; Hardegger, 1917, passim; idem in Hardegger-Schlatter-Schiess,

1922, passim.

For descriptions and reproductions of these drawings, see Poeschel,

1957, 38-39 and ibid., fig. 46 (Heinrich Vogtherr), figs. 53 and 54

Melchior Frank), fig. 56 (pen drawing of 1666) and fig. 57 (bird's-eye view

on parchment of 1671).

On the Protestant upheaval of 1712, see Hardegger, 1917, 1ff;

Hardegger-Schlatter-Schiess, 1922, 168ff; Poeschel, 1961, 65ff.

Before World War II, these drawings, bound into a fascicule, were

in the Stiftsarchiv of St. Gall (cf. Hardegger-Schlatter-Schiess, 1922,

173 note 1). After their evacuation during the war, their whereabouts

were no longer traceable (cf. Poeschel, 1961, 45, note 4).

VI.1.3

THE CLOISTER

It is clear that the cloister lay to the south of the church

where it still is today (although completely rebuilt), and it

is equally clear that the dormitory occupied the upper level

of the eastern range which adjoined the southern transept

arm precisely as on the Plan of St. Gall. This can be

inferred from Ekkehart's account of the ignominous visit

which Abbot Ruodman of Reichenau paid to the monastery

of St. Gall under the cover of night and the description

of the complicated route which he had to take in order to

get from the cloister to the monks' privy.[21]

From the same

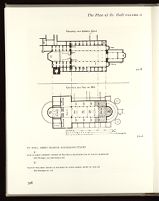

ST. GALL. ABBEY CHURCH. SUCCESSIVE STAGES

512.B

512.A

A.

PLAN OF ABBOT GOZBERT'S CHURCH OF 830-837 AS RECONSTRUCTED BY AUGUST HARDEGGER

[after Hardegger, 1917, plate facing p. 521]

B.

PLAN OF THE ABBEY CHURCH AS RECORDED BY PATER GABRIEL HECHT IN 1725-26

[after Hardegger, loc. cit.]

512.C ST. GALL. ABBEY CHURCH. LONGITUDINAL SECTION OF 1626-1756 AS RECONSTRUCTED BY

AUGUST HARDEGGER ON THE BASIS OF GABRIEL HECHT'S DRAWINGS OF 1725-26 (FIGS. 511.A-C)

[after Hardegger, 1922, 139]

FIGURES 512. A, B, C ARE SAME SCALE (CA.1:700)

Bays 3-9 of the nave and aisles were built by Gozbert and are the oldest parts, dating from 830-837. Otmar's church, dedicated 24

September 867, located west of Gozbert's church was originally separated from it by an entrance hall surmounted by St. Michael's chapel

which was dedicated 25 September 867 (cf. figs. 513.A-B, and figs. 507-509). The choir was entirely built by Eglolf, 1439-1483, on a ground

area co-extensive with the transept and choir of Gozbert's church that had been damaged by fire in 1418. In 1623-26 St. Michael's chapel

was demolished and Gozbert's church was enlarged westward by two bays, thus extending it all the way to Otmar's church.

the entrance of the church, as we would expect it to be in

the light of the Plan of St. Gall. Ekkehart IV mentions a

warming room (pyrale) in a context which suggests that in

the tenth and early eleventh century it was used for disciplinary

actions traditionally undertaken during chapter

meetings.[22] In the same chapter he also implies that the

washhouse (lavatorium) was reached from the warming

room; in fact the text seems to suggest that it was part of

this room. In departure from the Plan of St. Gall, however,

the Scriptorium was not on the north side of the church

but next to the pyrale.[23]

We know nothing about the location of the refectory

or the cellar but there is no reason to presume that they

were laid out in a manner other than that proposed on the

Plan. The Carolingian refectory and dormitory perished

in the great fire of 1418 and were completely rebuilt by

Abbot Eglolf (1427-1442).[24]

Ekkeharti (IV.) Casus sancti Galli, chap. 112; ed. Meyer von

Knonau, 1877, 379ff; ed. Helbling, 1958, 192-93.

VI.1.4

EXTRA-CLAUSTRAL BUILDINGS

Ekkehart's account of the fire of 937[25]

discloses that the

Outer School was located north of the church on a lot

which corresponded closely to the site it occupies on the

Plan of St Gall. The fire was set by a vindictive student in

the attic of the schoolhouse and was carried by the north

wind on to the roofs of the church and of the cloister.

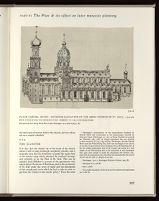

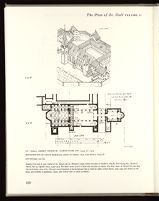

ST. GALL ABBEY CHURCH. CONDITION OF 1439 TO 1525

513.B

513.A

RECONSTRUCTION BY AUGUST HARDEGGER, BASED ON FRANK, 1507, AND HECHT, 1725-26

[after Hardegger, 1922, 69]

Reading from west to east: church of St. Otmar and St. Michael's chapel (above entrance to Gozbert's church), both dating 867; Gozbert's

church, 830-37; Eglolf's choir, 1439-1483; Hartmut's tower (SCHULTURM) near entrance to church, 872-883; tower of Ulrich (VI) von Sax

(FESTERTURM), 1204-1220. The four-storied building in the background (HELL) built by Abbot Ulrich Rösch, 1463-1491 (not shown on the

plan), was probably a guesthouse. (Dates after Otmar refer to tenure of abbots.)

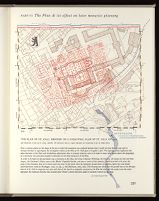

514. THE PLAN OF ST. GALL IMPOSED ON A CADASTRAL PLAN OF ST. GALL OF 1965

RED DRAWING, PLAN OF ST. GALL, SHOWN 1/8 ORIGINAL SIZE (1:1536) IMPOSED ON CADASTRAL PLAN AT SAME SCALE

Even a cursory glance at the shape of the site to which the monastery was confined discloses that it could not have been an easy task to

attempt literally to superimpose the rectangular scheme of the Plan of St. Gall upon so irregular a plot. The superimposition emphazises the

ideal character of the Plan and foreshadows adjustments that, in ensuing centuries, were to be made in many other places where the topography

of a particular site prevented complete realization of the ideal monastery of the Plan.

In order to be built on this particular site, as foreseen on the Plan, the Great Collective Workshop, the Granary, the houses for fowl and their

keepers, the Gardener's House, most of the Monks' Vegetable Garden, and even a corner of the cemetery, would have had to lie across the

gorge of the Steinach, that at its lowest point lay some 50 feet lower than the monastery ground level. (cf. caption, figure 505, and similar

superimpositions made by Hardegger, 1922, 22, fig. 3; and Edelmann, 1962, 289.) This drawing also shows that the ground area of the Baroque

church of St. Gall is congruent not only with that of the church as originally conceived on the Plan but also with the surface area the entire

aggregate the medieval churches had attained after Otmar's church had been added to Gozbert's church (cf. fig. 513).

On the Plan of St. Gall the Abbot's House is located

east of the Outer School in axial prolongation of the northern

transept arm of the Church. The palace (palatium),

built by Abbot Grimoald (841-847) with the aid of masons

from the imperial court (palatini magistri) was also to the

north of the church although further eastward. A deed

of 1414 reveals that it was furnished with a solarium; as is

stipulated on the Plan of St. Gall. Like most of the other

buildings it was gutted by the fire of 1418 and subsequently

completely reroofed as well as rebuilt internally by Abbot

Henry IV and his successor Eglolf (1427-43).[26]

On the

Ichnographia drawn by Gabriel Hecht in 1719, (fig. 510),

and in the bird's-eye view of the city of St. Gall issued by

Melchior Frank in 1595 (fig. 507), as well as on the anonymous

city view of 1666,[27]

this rebuilt variant of the

Carolingian palace is truthfully portrayed.

The original cemetery of the monks was east of the

monastery church between the chapel of St. Peter's and

the Steinach River[28]

on precisely the same location in

which it was shown on the Plan of St. Gall; and St.

Peter's itself[29]

(perhaps in conjunction with St. Catherine's

chapel) lay on the site that on the Plan is occupied by a

double chapel that served as oratories for the novices and

the sick. It consisted, as can be inferred from the city view

of Melchior Frank (fig. 507) and several other drawings, of

three contiguous building masses of varying width and

height arranged along the same axis.

Here our knowledge of the position of the offices of the

Carolingian monastery ends. Whatever evidence survives

of their original disposition is hidden in the ground. The

city and the canton of St. Gall, not to speak of the Confederation

of Switzerland, whose support would be needed

in a project of this magnitude, have not faced as yet the

challenge of clarifying this important historical problem

through a program (long overdue) of systematic excavations.

In the meantime it must be underscored that in those

cases for which historical evidence is available, the layout

of Gozbert's monastery appears to have conformed with

the scheme of the Plan. This condition may even have

applied to most of the unknown sectors of the site, except

for the Hen and Goose Houses in the southeastern corner

of the Plan. Their location is in conflict with the relief of

the actual plateau on which the abbey rose. Here the steep

embankment of the Steinach River, that swings sharply

toward the north, would have called for adjustments that

might also have affected some of the neighboring buildings.

A glance at the city view of Melchior Frank (fig. 507) and

the photographs of the monastery site, forming part of the

magnificent model reconstruction of the city of St. Gall,

made in 1919-22 by architect Salomon Schlatter (figs. 508

and 509) reveals this condition with great clarity. In

figure 514 we have superimposed the course of the river

and other boundaries of the monastery site upon the scheme

of the Plan. The axis of the church is given by its still-existing

crypt. The superimposition shows that between

the church and the Steinach there is sufficient room for all

of the buildings that on the Plan are located to the south of

the Church. The houses for the animals and their keepers to

the west of the Church, could easily have been accommodated

in the great area that now is occupied by the St.

Gallus Platz.[30]

The original entrance to the monastery was

in the west, as it is on the Plan of St. Gall, through the

Gallustor (later: Grüner Turm).[31]

The only truly distinctive

difference between the scheme of the Plan and the actual

monastery was that Gozbert's church did not terminate

with an apse in the west—understandably so because in

St. Gall, St. Peter, to whom this apse is dedicated on the

Plan, had already a sanctuary of his own.[32]

In the Abbey of

St. Gall, instead, this area was occupied by a chapel

dedicated to St. Otmar and connected with the church by

an open porch that was surmounted by an oratory dedicated

to St. Michael (fig. 513). St. Otmar's chapel was built by

Abbot Grimald and consecrated on September 24, 867 by

Bishop Salomon.[33]

It rose on the space that was released on

the actual building site by the reduction of the church as

originally drawn on the Plan from 300 to 200 feet. The only

point in which Hardegger failed was that in his reconstruction

drawings of Gozbert's church (fig. 512A) he did not

remain faithful to his own argument but allowed the two

transept arms to project beyond the masonry of the Gothic

choir (obviously in the desire to make them more fully

conform with the Plan). H. R. Sennhauser informs me that

this was not borne out by excavations conducted under the

pavement of the present church, which showed that the

circumference walls of the Gothic choir rose indeed, as

Hardegger had postulated, on the foundations of the

corresponding Carolingian work (see below, pp. 358-59).

FRANCISC (FRANZISKA, FRANSISQUE)

A favorite weapon of the Franks, wielded with great dexterity as a battle axe, often hurled.

Ekkeharti (IV.) Casus sancti Galli, chap. 67; ed. Meyer von Knonau,

1877, 240-43; ed. Helbling, 1958, 127-28.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||