The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V.1.1.. |

| V.1.2. |

| V.1.3. |

| V.1.4. |

| V. 2. |

| V.2.1. |

| 10. |

| 10. |

| V.2.2. | V.2.2 |

| V. 3. |

| V.3.1. |

| V.3.2. |

| V.3.3. |

| V. 4. |

| V.4.1. |

| V.4.2. |

| V.4.3. |

| V. 5. |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

| V. 6. |

| V.6.1. |

| V.6.2. |

| V.6.3. |

| V.6.4. |

| V. 7. |

| V.7.1. |

| V.7.2. |

| V.7.3. |

| V.7.4. |

| V.7.5. |

| V.7.6. |

| V. 8. |

| V.8.1. |

| V.8.2. |

| V.8.3. |

| V.8.4. |

| V.8.5. |

| V.8.6. |

| V.8.7. |

| V.8.8. |

| V. 9. |

| V.9.1. |

| V.9.2. |

| V.9.3. |

| V. 10. |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. |

| V. 11. |

| V.11.1. |

| V.11.2. |

| V.11.3. |

| V. 12. |

| V.12.1. |

| V.12.2. |

| V.12.3. |

| V. 13. |

| V.13.1. |

| V.13.2. |

| V. 14. |

| V.14.1. |

| V.14.2. |

| V. 15. |

| V.15.1. |

| V.15.2. |

| V.15.3. |

| V.15.4. |

| V. 16. |

| V.16.1. |

| V.16.2. |

| V.16.3. |

| V.16.4. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| V.18.1. |

| V.18.2. |

| V.18.3. |

| V.18.4. |

| V.18.5. |

| VI. |

| VI. 1. |

| VI.I.I. |

| VI.1.2. |

| VI.1.3. |

| VI.1.4. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI.2.1. |

| VI.2.2. |

| VI.2.3. |

| VI.2.4. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI.3.1. |

| VI.3.2. |

| VI.3.3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI.4.1. |

| VI.4.2. |

| VI.4.3. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V.2.2

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

Until the end of the second decade of this century the

literary sources discussed on the preceding pages were all

that students of early medieval house construction had to

lean on when discussing the question of Northern parallels

for the guest and service structures of the Plan of St. Gall.

To be sure, some isolated excavations had already been

made in Sweden and Iceland,[100]

but this fact was not

widely known; and the procedure for unearthing houses

whose structural members, in many cases, could be identified

only by a shadowy patch of soil discoloration left in

the ground as they rotted away, had as yet not developed

into that highly accomplished technique so successfully

practiced today. But in 1928-1931 this situation began to

change when John and Nils Nihlen laid bare on the island

of Gotland two three-aisles houses of the Migration Period

which looked like physical embodiments of Gudmundsson's

Saga house. In 1930-1934 the Dutch anthropologist Albert

Egges van Giffen initiated a new era of northern house

research with the excavation of an Iron Age dwelling

mound in a hamlet called Ezinge (Groningen) in Holland,

which revealed that a very similar type of dwelling was in

use as early as the fourth century B.C. in the territory of the

Frisians, a West Germanic tribe. In the two following

decades the information gathered from these excavations

was broadened by an increasing number of further discoveries.

At the date of this writing we are able to trace, on

the basis of several hundred excavated dwellings, the

development of the timbered three-aisled house in the

Germanic territories of transalpine Europe from its beginnings

in the Middle Bronze Age through the Iron Age, into

the Early Middle Ages, and through the Middle Ages to

its modern survival form

KÄNNE, BURS, GOTLAND, SWEDEN

The first example of this long line of excavations, as just

remarked, was a three-aisled dwelling, excavated in 1928 by

John and Nils Nihlen, in a place called Känne, in the

parish of Burs, in East Gotland (fig. 290).[101]

It was 33 feet

wide (10 m.) and had the extraordinary length—not as

yet matched by any dwelling subsequently unearthed—of

203 feet (62 m.) A recent review of the site has disclosed

that the hall was constructed in two successive phases, and

in its original state was only half as long.[102]

Its roof was

supported by two rows of freestanding inner posts, rising

in pairs, at intervals of 9 to 13 feet (3 to 4 m.). Each of

these uprights was firmly secured in the ground by a

ring-shaped wrapping of stones. Over fifty charred beams

and numerous fragments of wood were found on the floor;

among these were the remains of two large beams which

were jointed into each other at right angles. The walls

consisted of solid banks of earth heavily interspersed with

small stones and were faced, outwardly and inwardly, with

a strong lining of heavier stones. The roof must have been

covered with sods of turf, as no other material would have

smothered so effectively the fire that destroyed the house

yet preserved so much of the timbered frame of the roof.

The hall received its warmth from two hearths which lay in

the middle of the center aisle, one of them 33 feet (10 m.)

long. "Longfires" of this kind are well attested from the

Sagas, where they are referred to as langeldar or máleldar.[103]

The general character of the accessories found in the house

pointed to about the year A.D. 200 as the approximate

period of construction.

These were the conclusions of Arne Biörnstad as expressed in

Vallhagar, ed. Stenberger and Klindt-Jensen, II, 1955, 886-92.

A typical case in point is to be found in the Njal's Saga: "There

had been much rain that day, and men got wet, so long fires were made"

(Regn hafdi verit mikit um daginn, ok höfdu menn ordit vátir, ok vóru

gorvir máleldar); see Brennu-Njálssaga, ed. Jonsson, 1908, 23. Or, a well

known passage in the Prose Edda, where we are told how Thor, as he

stepped into the hall of Geirrôdr, observed that "there were great fires

down the entire length of the hall" (par voru eldar stórir eptir endilangri

höllini); cf. Edda Snorra Sturlusonar, ed. Legati Arnamagnaeani, I,

1848, 288.

LÖJSTA, GOTLAND, SWEDEN

The second house, a structure of more normal proportions,

85 feet by 33½ feet (26 m. × 10.5 m.), was excavated in

the summer of 1929 in the vicinity of castle Lojsta in

Gotland (fig. 291A-C).[104]

It was the same construction type

except that here the roof-supporting posts were not sunk

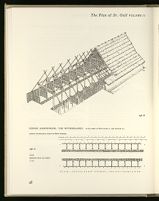

298.B EZINGE (GRONINGEN), THE NETHERLANDS. CATTLE BARN OF Warf-LAYER IV, 2nd CENTURY B.C.

[author's reconstruction, drawn by Walter Schwarz]

298.A PLAN

REDRAWN FROM VAN GIFFEN

1:150

299. EZINGE (GRONINGEN), THE NETHERLANDS. CATTLE BARN OF Warf-LAYER IV, 2nd CENTURY B.C.

[excavation photo by courtesy of A. E. Van Giffen]

This building, like those unearthed above and beneath it, owes its magnificent state of preservation to the fact that each settlement stratum in

which houses were buried in the course of successive inundations was sealed by sterile layers of sand and clay deposited after flooding, sealing

their content against the infiltration of air and thus protecting it from decay. The roof-supporting posts of oak, the braided walls and cross

partitions (wattled saplings of birch) were preserved to a height of 4 feet. The manure mats were found to be in such good condition that they

could be walked upon without breaking. The building was 29 feet wide (7.20m) and over 75 feet long (23m) but was never excavated to its full

length. Its construction was identical with that of the houses found in the earlier Warf layers (figs. 293-297).

The systematic division of the aisles into stalls, together with the absence of any fireplaces, suggests that it was used for the stabling of livestock

exclusively. Since every stall had room for two head of cattle, this barn must have been able to hold at least 48 animals, striking evidence of

the economic wealth of these early shoreland farmers. Livestock entered and left the building through doors in the two narrow ends—a feature

found in many other early Iron Age houses (figs. 304, 310, 312, 315, 316), and today in the Lower Saxon Wohnstallhaus and the Frisian

Los-hus, modern descendants of this building type.

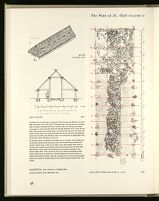

PRE- & PROTOHISTORIC CARPENTRY JOINTS

300.A

300.B

300.C

300.D

[after Zippelius, 1954, figs. 1, 2, & 5]

A. Forked posts (Neolithic)

B. Post with slit head

C. Mortice and tenon joint in post and plate assemblage

(Neolithic)

D. Mortice and tenon joint in post and ground sill assemblage

(Bronze Age)

stones were still in their original position (fig. 291A). The

posts themselves had disappeared. Rising freely from stones

as they did, they could only retain their vertical position by

being framed together at the top by means of cross beams

and long beams. Slight irregularities in the longitudinal

alignment of the posts suggested that the cross beams lay

underneath the long beams. The excavators felt so sure of

their interpretation of these conditions that they undertook

to reconstruct the entire hall on its original site (figs. 291B

and C). Some of the details of this reconstruction have since

been questioned, but the doubts amount basically to no

more than that in the original house the walls were probably

a little higher than they are shown at present.[105] The

pottery found in the house suggests as period of construction

the third century A.D. In the fifth century, for unknown

reasons, the hall appears to have been abandoned.

In the two decades that followed probably more than

sixty houses of the Lojsta type were unearthed on the

islands of Gotland and Öland, on the mainland of Sweden,

in Norway and in Denmark,[106]

and, last but not least, in

Iceland, the country whose literary tradition introduced us

to this type of dwelling.

The Swedish material is surveyed in exemplary publications, such

as the work of Nihlen and Böethius on the Iron Age farmsteads of Gotland,

and the corresponding volume by Stenberger on the Iron Age

farmsteads of Öland (both published in 1933), and the magnificent

collective work on Vallhagar, edited in two volumes by Stenberger and

Klindt-Jensen, 1955.

The Norwegian material excavated prior to 1942 is summarized in

Grieg, 1942.

For the Danish material prior to 1937 see Hatt, 1937. For later material

see Nørlund's splendid account on Trelleborg, published in 1948,

and the excavation reports by Hatt and others listed in Hatt's latest

great work, on the Iron Age village of Nørre Fjand, published in 1957,

as well as a number of articles that have appeared during the last two

decades in the Danish series Fra Nationalmuseets Arbejdsmark (Copenhagen,

Nationalmuseet, 1928ff).

STÖNG, ÞÓRSÁRDALUR VALLEY, ICELAND

Iceland was the subject of an expedition undertaken between

1934 and 1939 by a joint excavation team of Danish,

Swedish, Norwegian, Finnish, and Icelandic archaeologists.[107]

I show as a typical example of the results of this

expedition, the plan and excavation photos of the dwelling

of a farm called Stöng in þórsárdalur Valley (fig. 292A-C)

which was settled during the landnám period at the end of

the ninth century and covered by the ashes of nearby

Mount Hekla in an eruption in the year 1300. The dwelling

unit of this farmstead consisted of a long house 98 feet

long, divided into foreroom, sleeping house, living house

(forstofa, area I; skáli, area II; stofa, area III), milkhouse

(area IV), and cooler (area V). The sleeping hall was

54 feet long and 19 feet wide. Its aisles were raised so

as to form continuous "benches"—the langpallar of

Gudmundsson's Saga house. Inserted into the curbs

of these benches about every 6 feet were large blocks

which served as base stones for the wooden uprights that

once supported the roof of the hall (fig. 292B). The fireplace

lay in the middle of the center floor. Two shallow stone

foundations which bisected the aisles crosswise suggest that

the sleeping hall was subdivided by means of wooden cross

partitions into a sleeping house for men (karlskáli) and

another for women (kvennaskáli)—a distinction also well

known from the Sagas. And judging from the presence of

two rows of stones ranged carefully along the base line of

the two long walls, the hall must have been wainscotted

its entire length (the veggþili or langþili of the Sagas).

There was a "crossbench" (þverpallr) on the entrance

side of the hall, raised like the aisles and screened off by a

wooden cross wall. I am drawing attention to this house not

evidence that established the correctness of Gudmundsson's

literary work, but also because this dwelling may date from

the same century in which the Plan of St. Gall was drawn.

During the Iceland expedition of 1934-39 a total of eight

such houses was unearthed. But by the time these excavations

were conducted, discoveries of even greater significance

were in progress on the Continent.

For Iceland, see the collective report on prehistoric farmsteads

excavated in 1939, ed. Stenberger, 1943.

EZINGE, PROV. GRONINGEN, THE NETHERLANDS

The low-lying coastlands of the Netherlands and northern PLAN [after Bloemen, 1933, 6, fig. 6] These aisled Iron Age houses are sited on a small chain of hills PLAN [after Bloemen, 1933, 6, fig. 7] Alternation of heavy posts with saplings in the outer walls of both

Germany are dotted with man-made circular earthen works

on which the cattle-raising Iron Age settlers of this territory

erected their dwellings in order to protect themselves from

the heavy tides that flooded the surrounding flatlands

during the storms that lashed the shores of the North Sea

in the winter and spring. These dwelling mounds, called

Warfen or Wurten in German,[108]

terpen in Dutch,[109]

are

the product of the struggle of man against a geophysical

event of major importance which started some ten thousand

years ago, has as yet not subsided, and is even today only

temporarily checked by an elaborate system of dikes. Since

the retreat of the last great glacial cap of ice the shorelands

of Holland and northwestern Germany have gradually

sunk away in the course of a geological action in which long

periods of sinking alternated with shorter and less effective

periods of uplift.[110]

The last of these cycles of sinking

started in the centuries immediately preceding the birth

of Christ and is still in progress. Prior to its inception the

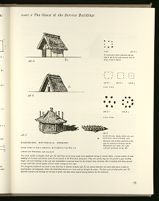

301. WIJCHEN (GELDERLAND), THE NETHERLANDS

flanking a depression that may once have formed an outer arm of the

river Maas. Impressions of poles in the axis of both buildings (see

fig. 302) suggest they carried ridge purlins as did the house of the

Lex Bajuvariorum (figs. 289.A-B).302. WIJCHEN (GELDERLAND), THE NETHERLANDS

houses reveals that the braided wattle walls did not form an

independent envelope, as with the Ezinge houses, but stood in line

with the outer posts.

303.A FOCHTELOO (FRIESLAND), THE NETHERLANDS

HOUSES OF A WEALTHY WEST GERMANIC FARMER AND HIS FOLLOWERS, 1ST-4TH CENTURIES A.D.

303.A VIEW FROM THE AIR LOOKING NORTHWARD. RECONSTRUCTION BY A. E. VAN GIFFEN, 1954, fig. 85 [drawing based on a sketch by L. Posterna]

303.B PLAN OF SETTLEMENT SHOWN IN AIRVIEW

303.B

This large dwelling was associated with a hamlet of three

similar houses approximately the same width, but only half

its length. It was excavated in 1938 on a sandy elevation

of the Dutch Geest. The presence of roof-supporting timbers

was determined by discoloration in the ground from where

they had rotted away. By this evidence it was ascertained

that the roof of the main house was supported by two rows

of free-standing inner posts, ten in each row, and that they

were of quarter-split oak sunk, rounded side inward, 0.75m

into the earth. This building was buttressed by a large

number of exterior posts set at an angle to help neutralize

the outward thrust of the roof. The walls were of wattle-daubed

clay; the rounded corners and absence of any timbers

capable of supporting a gable suggest that the building's

roof was hipped over its narrow ends. Both main house and

adjacent hamlet were protected by a pallisaded fence, and

the main house additionally by a ditch.

Holland lay level with the flat land; but as the land began

to sink away, the water of the North Sea rushed in with

steadily increasing frequency and furor, and forced the

settlers to remove their dwellings to successively higher

levels. This they did by packing the floor level of their

houses with thick layers of turves and animal manure and

by re-erecting new dwellings on these mounds above the

inundation level of the heavy winter tides. As this process

continued century by century, it gave rise to a landscape of

man-made dwelling mounds attaining in their ultimate

stage a diameter of twelve or fifteen hundred feet and a

maximum inner height above the surrounding land of as

much as twelve to eighteen feet.

The effects, although not the cause, of this peculiar

geological phenomenon were known to Pliny the Elder,

who visited this territory probably in A.D. 47 and transmitted

his observations to posterity in a derisive yet

highly descriptive passage of his Historia Naturalis:

There, in a region of which one may wonder whether it belongs to

the sea or to the land, a miserable race of people dwell on elevated

mounds or platforms, thrown up by hand [tumulos optinent altos

aut tribunalia extructa manibus], in houses erected above the level

of the highest tide, resembling men who travel in ships, when the

water floods the surrounding land, and shipwrecked people when

the waters have dispersed.[111]

A vertical profile cut through such a tumulus or Warf

shows as a rule a sequence of several convex layers of soil

in different coloration; the cultural remains reveal layer by

layer the story of the settlement as it was abandoned and

re-erected on each successive level. The physical composition

of these mounds offers unusually favorable conditions

for the preservation of organic materials, such as wooden

uprights, wattled fences or walls, or even objects made of

leather, since each abandoned settlement was covered by a

solid layer of clay which sealed its contents against the

corrosive action of the air.

In 1930 Albert Egges van Giffen dug a trial ditch through

a mound of this type at Ezinge (Groningen), Holland, and

the ensuing excavation (1932-34)—a landmark in the history

of European house research—enabled him to trace the

development of a West-Germanic settlement from its

beginnings in the fourth century B.C. to its end in the third

century A.D.[112]

The earliest settlement of this site (layer VI) was a

single farmstead (figs. 293 and 294), erected early in the

fourth century B.C. on the natural ground of the flatland. It

consisted of a three-aisled house with walls of wattlework,

and a vast enclosure almost entirely taken up by a platform

for the storage of hay or harvest. The timbers of the roof of

the house had disappeared, but the roof-supporting posts

and the braided walls of the house were preserved to a height

of almost a feet (fig. 293). They consisted of five pairs of

freestandings inner posts and a perimeter of thinner outer

posts. The wattle walls ran independently of this system,

slightly inside the ring of outer posts.

FOCHTELOO (FRIESLAND),

THE NETHERLANDS

304.A

304.B

HOUSE OF A WEALTHY GERMANIC FARMER

1ST-4TH CENTURIES A.D.

PLAN AT LARGE SCALE (A. E. VAN GIFFEN)

Plan of the main house (A) shows that aisles of the six westermost bays are cross

partitioned into stalls for 24 cattle. Entrances in the middle of each long wall lead to a

center bay that separates stock from the dwelling (four eastern bays). B and C: Plans

of the main house, final condition.

305.A LEENS (GRONINGEN), THE NETHERLANDS

AISLED HOUSE WITH TURF WALLS, A.D. 700-1000

PLAN [after A. E. Van Giffen, 1935-40, fig. 16]

The plan above is at level B noted on the transverse section below

306.A) with horizontal fold shading. Shown at right (306.B) is another

building.

305.B SECTION, EXCAVATION,

scale horizontally & vertically, 1:150

Ground penetration at right is about 3.5m = 11.5 ft.

LEENS (GRONINGEN), THE NETHERLANDS

306.A

306.B

AISLED HOUSE WITH WALLS, A.D. 700-1000

TRANSVERSE SECTION [after Zippellius, 1953, 32, fig. 5f]

Dwellings excavated at Leens were of great historical importance since they offered the

first archaeological proof that the aisled Germanic Wohnstallhaus continued to be built

in the Middle Ages. Fig. 306.A shows a house of Warf layer B of seven strata

spanning roughly 3 centuries. The structure was 38 feet long, 16 wide (11.5 × 4.8m).

Layer B also held a house with wattlework walls, the soil structure of which indicated

it was almost 72 feet long.

When the water level of the North Sea had risen high

enough to make living on the flatland intolerable, the

single family dwelling of layer VI was buried under a

man-made mound of sods and turves (layer V) which,

after having reached a height of roughly 4 feet and a diameter

of approximately 90 feet, gave birth to a hamlet that

now comprised a total of five houses (figs. 295-297). These

houses belonged to the same construction type as did the

preceding settlement and were equally well preserved.

Three of them were provided with hearths, and hence

must have served as dwellings for people; one was inhabited

by both men and animals, evidenced by the

presence of both a hearth and two narrow strips of wattle-work

in front of the roof posts, which the excavator

interpreted as fodder mats, but which later excavations

proved to be dung mats.[113]

The same condition appears to

have existed in the large house in the center, if this house,

as seems likely, had a hearth in its unexcavated eastern

section. Another smaller house, built at right angles against

this dwelling, had neither hearth nor dung mats, and hence

may have served as barn or general storage area. In the

houses that accommodated livestock the aisles were subdivided

into bays, or stalls, by means of braided cross

partitions, each of the thus-created boxes yielding sufficient

space for the stabling of two heads of cattle, facing the

outer wall perimeter of the house. Three of the houses had

their entrance broadside, two were entered axially. Pottery

shards and other cultural accessories associated with this

settlement permit a rough dating of the third century B.C.

In the second century B.C. the hamlet of layer V was

abandoned and the mound on which it stood was enlarged

to more than twice its original diameter and raised to a

level of 6 feet above the natural ground. On top of this

elevation a new village was built in a circle around an

open yard with the longitudinal axes of the house pointing

radially to the center of the Warf (layer IV).

The houses of this layer were of the same construction as

those of the preceding layers, but in general considerably

more spacious, as one may gather by glancing at the

extraordinary cattle barn reproduced in figures 298-299.

It had a length of over 75 feet (23 m.) even in its uncompleted

state of excavation. The posts and carefully

braided walls of this structure (twigs of birch daubed with

cow manure) were preserved in almost original freshness,

in spots to hip and even shoulder height. The building

contained no hearth, but dung mats ran along the inner

roof supports along the entire length of the structure, and

the aisles were systematically subdivided into stalls by

braided cross partitions.

The circular village to which this barn belonged was in

use from the second century B.C. to the first century A.D.,

but the life span of its houses was found to be considerably

shorter than that of the preceding layers. In certain sectors

van Giffen found that five to ten houses had been superimposed

upon one another in rapid succession; and intermittent

stratification of this settlement horizon with sterile

307. HODORF (HOLSTEIN), GERMANY

AISLED FARM HOUSE, 1st-2nd CENT. A.D.

PLAN [by W. Haarnagel; after Schwantes, 1939, 272, fig. 10]

At the lowest level of the Hodorf WARF lay a flatland farm consisting of a

three-aisled main house divided into living and livestock areas, and an unaisled

barn built in axial prolongation of the house. In the layout of the plan two

measures are clearly discernible, the longitudinal measure of column interval A

and its half measure A/2. This measure and submeasure make up the length of

the house and its AMBAU (= 111 feet). The width of the house (17 feet) appears

to be uniformly twice that of the center aisle. While the observation is simple and

even superficial, it hints, at this period and in this region, of an emerging

awareness of systematic measure in simple building practice and agriculture. All

trace of bulging curvature of wall line, or boat-like plan, has disappeared in

favor of a rather uniform rectangular geometry. Discipline of measure prevails

over scattered spacing and casual positioning of posts. A knot tied midway

between the ends of a braided rope could graphically solve the problem of

division by 2 for men unversed in the mystery of abstract arithmetic. It would,

too, lead to successive halving in series.

initial stages at least, was still dangerously exposed to the

destructive action of the heavy winter tides.

In the centuries that followed, the second and third

centuries A.D., the Warf had to be raised again on two

successive occasions (layer IV-III). The house type remained

the same, except that in the later stages the wattle

walls were frequently reinforced externally by heavy layers

of turf. Toward the close of the third century, finally, the

village perished in a fire—an event that van Giffen connected

with the intrusion into the Frisian territory of the

first westward-moving Anglo-Saxons. The spacious three-aisled

houses were now superseded by small rectangular

huts which are of no interest to this study.

The excavation photos shown in figures 293 and 299 convey

in persuasive terms the unusual state of preservation in

which the Ezinge houses were found. They furnished

conclusive evidence about the construction of the walls and

the nature of the principal roof-supporting members (in

places preserved to a height of 4 feet above the ground),

but they told us nothing about the manner in which these

members were framed together at the top into a stable

roof-supporting system, nor how the roof itself was constructed.

There are, nevertheless, a few inferences that can be

made with relative safety from the conditions of the walls

and the placement of the posts. One of these is that the

roof must have been hipped over the narrow ends of the

house. This must be inferred from the fact that the two

end-walls of the house are not provided with posts that

could have carried a gable. The reconstruction of the roof

shapes shown in figures 295 and 297 render this condition

correctly.[114]

Second, the principal posts must have been

framed together lengthwise by long beams which were

needed for the support of the rafters. There is no unity of

opinion, however, on whether the posts were in addition

connected transversely by crossbeams. Van Giffen felt

that, provided the posts were set sufficiently deep into the

ground, no such cross-connections were needed; and this

was also, in part at least, the opinion of Joseph Schepers.[115]

The technical soundness of this view, however, was questioned

308. HODORF (HOLSTEIN), GERMANY

EXTERIOR VIEW, AISLED HOUSE

1st-3rd CENTURIES A.D.

[by courtesy of W. Haarnagel]

Although conjectural in many details, this model in the

Niedersachsische Landesstelle für Marschen- und Wurtenforschung,

Wilhelmshaven, is nevertheless a very convincing reconstruction of

the main house of the flatland farm of Hodorf unearthed in 1936-37.

It demonstrates that the Lower Saxon Wohnstallhaus,

surviving examples of which date only to the 15th century, is in fact

a modern derivative of a prehistoric building type.

As in the similar Ezinge houses, the rafters of the roof were carried

by a row of posts placed slightly outside the independent wattle

walls. The rounded corners of these walls, and the absence of any

strong support at the building's narrow ends, suggest that its roof

was hipped. Four round posts around the hearth (fig. 307) and

unaligned with the principal posts, are correctly interpreted as

supports for a canopy raised slightly above the main roof with lateral

openings for light, and smoke escape—a device well known through

the Sagas (see p. 23ff) and crucial for interpretation of the guest

and service buildings of the Plan of St. Gall (see below, pp. 117ff).

pointed out that if the posts were only connected by long

beams, the roof-supporting frame would still be exposed

to the danger of bending and buckling under the strain of

heavy loads of snow or the thrust of the wind during

storms. Moreover, cross connection is suggested by the

extremely accurate transverse alignment of the post, as it is

found in all of the Ezinge houses, as well as in the majority

of Warf dwellings subsequently unearthed. Whether the

cross beams lay beneath the longitudinal timbers, or above

them, must remain an open question.

There appears to be general agreement that the peripheral

row of posts—standing either within the walls of the house

or at a slight distance away from them—consisted of

short uprights terminating in a fork and carrying in that

fork a course of horizontal timbers which served as footing

for the rafters. The wattle walls themselves would have

been too weak to carry the roof. In some of the Ezinge

houses the outer posts were found to lean inward in close

adjustment to the angle of the roof thrust—a feature that

was encountered again in many houses subsequently

unearthed.[117]

The construction of the roof itself has been the subject

of some penetrating, yet careful and equally cautious,

observations made by Adelhart Zippelius.[118]

Zippelius feels

that the layout of the Ezinge houses suggests that they were

covered by a continuous sequence of coupled rafters

(Sparrendach). The absence of any trace of posts along the

central axis of the house precludes the assumption of a

ridge pole. In primitive ridge-pole construction the two

sides of the roof were, in general, formed by means of

poles (in German called Rofe) which were hooked into the

ridge piece with their heavy ends upward and suspended

in the pole by a hook formed by the stub of a former

branch. This type of roof construction (Rofenkonstruktion),

ideal for houses of relatively smaller dimensions, could also

be employed in connection with aisled houses, but only if

the width of the nave was not much greater than the width

of the aisles.[119]

Zippelius contends that in the Ezinge houses,

where the nave is generally twice the width of the aisles,

this system would not have worked, since the overhanging

portions of the roof poles (over the nave) would have outweighed

the lower portion of the roof, which covered the

aisles. The structural stability of the Ezinge houses required

that the roof poles were laid upon the supporting frame

with their light ends upward. Conjectural as all this may

be, it is based on sound speculation, and in the absence of

more tangible archaeological evidence provides us with as

good a working hypothesis as can be found at present.

Zippelius made some further, no less persuasive, assumptions

about the manner in which these timbers might have

been jointed. The easiest, simplest, and oldest method of

carrying a horizontal log is to lay it upon a row of timbers

terminating in a natural fork (fig. 300A)—a method that

continued to be employed long after more sophisticated

forms of joining had come into use, and is practiced even

EINSWARDEN (NORDENHEIM), GERMANY

309.B

309.A

POST AND WATTLE HOUSE, around the birth of Christ

PLAN AND RECONSTRUCTION [after Zippellius, 1953, 38, fig. 8]

The site is on the estuary of the river Weser. The construction of

this house is virtually identical in all respects with the houses of the

cluster settlement of Layer V of the Ezinge Warf (figs. 295-97 and

fig. 327). Like most of those, as well as the chieftains's house at

Fochteloo (fig. 304), its living quarters (two westernmost bays) are

separated from the stables (two easternmost bays) by a center bay

entered through a door in the middle of the southern long wall,

while the cattle enter through a door in the eastern end wall. The

house is 33 feet long and 16½ feet wide.

natural forks of the desired height could not be found

among the available logs, the fork had to be shaped with

tools. The closest man-made imitation of the natural fork—

and here again I think Zippelius is correct—is a joint to

which he refers as Pfostenzange and which is obtained by

simply cogging the notched portion of a large beam into a

corresponding slit in the head of the upright beneath it

(fig. 300B). Another way of locking posts into horizontal

timbers (either at the top, bottom, or in-between) is by

means of mortice and tenon joints (Verzapfung), as shown

in figure 300C and D, or by halving them into one another.

Halving would also appear to be the most sensible joint for

the tips of the rafters, the connections being given additional

strength at this point, perhaps, by some braided strands of

willow. The reconstructions shown in figures 297 and 298

attempt to conform with this thinking.[120]

Warf: Old Frisian: warf, werf; New High German: werfen, "to

throw," but originally perhaps in the sense of "to whirl" ("a circular

mound created by the whirling action of the sand"); cf. Grimm, XIII,

1910, cols. 2012ff. Wurt: Old Frisian wort, related to Middle High

German worfen; cf. Heyse, 1849, 1990.

terp: Old Frisian thorp; New High German: Dorf; related to Greek

τύρβη; Latin: turba, "a gathering of small people in the open field," and

hence "a rural settlement;" cf. Franck's Etymologisch Woordenboek,

1929, 695 and 127, where it is related to the Indo-European word

*tereb- "to cut, to hoe;" cf. also Grimm, II, 1860, cols. 1276ff, under

"Dorf."

Plinius, Historia naturalis, Book XVI, chap. 1; cf. Pliny, Natural

History, ed. Rackham, 1952, 387, 389. (The English translation, here

quoted, is my own).

Van Giffen's interpretation of these mats as "fodder mats" was

questioned by Helmers, 1943, who interpreted them as "manure" mats,

in analogy with the later Frisian farmhouse, where the cattle invariably

stood with the head to the wall of the house. His interpretation was

confirmed when, in subsequent excavations, sewage trenches were

discovered in the place of, or running parallel to, the wattlework mats

(Wilhelmshaven-Hessens, Elisenhof; see below, p. 59, n.85 and p. 69.

The reconstruction shown in fig. 295 is taken from Reinerth, I,

1940, 88, fig. 25. The others are my own.

Van Giffen, "Der Warf . . . ," 1936; and idem, "Die Siedlunge . . . ,"

1936, 191: "Ankerbalken dürfen noch nicht angenommen werden,

Kehlbalken mögen dagewesen sein." Schepers, 1943 (Plate 9, fig. 58)

published a reconstruction of one of the Ezinge houses which shows the

terminal pairs of posts connected by tie beams, the ones farther inward

not so connected.

Most markedly so on the Elisenhof near Tönning (figs. 319 and 320

below, and Bantelmann, 1964, 233, as well as plate 62, figs. 1 and 2);

but also in Einswarden (fig. 309 below) and Haarnagel, 1939, 269; and in

Warendorf (see Winkelmann, 1954; and idem,).

A typical example of a house making use of this type of construction,

according to Zippelius, is house 22 of a Celtic Hallstatt settlement on

the Goldberg, dating from about 800 B.C. (Zippelius, 1953, 19, fig. 2).

Both reconstructions were made before I had an opportunity to

familiarize myself with Dr. Zippelius' thinking. Fig. 298 is a revision of

and supersedes, an earlier reconstruction of this cattle barn which I

had published in an article dealing with the origins of the medieval bay

system (see Horn, 1958, 6, fig. 9).

WIJCHEN, MAAS ESTUARY, THE NETHERLANDS

When the Ezinge houses were discovered in 1930-34 they

were a new and entirely isolated phenomenon on the

Continent. But in the five years that followed, before the

outbreak of World War II, every subsequent summer

brought new results. While van Giffen was still at work at

Ezinge, F. Bloemen unearthed under less favorable soil

conditions another group of aisled houses of the first

century B.C. on a mountain range near the estuary of the

river Maas, near Wijchen.[121]

The ground plans showed the

transverse alignment of inner and outer posts, which was

typical of the houses of layer V and IV of the Ezinge Warf.

The outer walls consisted of an alternating sequence of one

heavy and two lighter posts; the heavy posts stood in line

with the principal posts (figs. 301, 302). In other aspects,

however, the construction differed. The houses had posts

along their central axes, an arrangement that is in general

interpreted as an indication of the presence of a ridge pole.

The excavation showed that ridge-pole construction, although

unusual, was nevertheless not absent in this territory,

an observation that was confirmed by later finds in

other places.[122]

310.X ISOMETRIC VIEW

310. CROSS SECTION

The house was 102 feet long, 29 feet wide. The nave and one aisle were 10½ feet

wide, the narrow aisle 8 feet wide. The distribution of stones—some for pavement

some for lining or packing of wall-post sockets, others for footing of principal

roof supports—reveals that the house was divided lengthwise into a nave and two

aisles, and crosswise into fourteen bays. In the first ten, only the center floor was

paved, and the aisles were strewn with sand. In the last four bays the pavement

ran across the width of the dwelling. This is the well-known T-shaped floor plan

of the Lower Saxon Wohnstallhaus.

In the house above, bay depth in the stable was 6½ to 8¼ feet. In the living area

the distance between trusses increased, and in the terminal bay containing the

hearth is almost twice as deep as the others. Since the principal inner posts of

the house were footed on stone blocks rather than in post holes, they must have

been framed at their heads by long beams and cross beams somewhat in the

manner shown above. The ANKERBALKEN (cross beams terminating in long

tenons morticed into the main posts a few feet below the tie beams) shown in

Rieck's reconstruction (Reick, 1942, fig. 2) appeared to us to be an anachronistic

feature for so early a structure and for that reason has been omitted in our cross

section.

AALBURG, near BEFORT, LUXEMBOURG

AISLED HOUSE, 5TH CENTURY B.C.

311. PLAN [after G. Rieck, 1942, 27, fig. 1] 1:125

On the Warf Feddersen Wierde, see below, pp. 59ff and Haarnagel,

1963, 288; on Warendorf, see below, pp. 76ff and Winkelmann, 1954,

211, fig. 3; and on the Elisenhof, see below, pp. 69ff and Bantelmann,

1964, 233.

FOCHTELOO, RHEE, SLEEN, AND LEENS,

THE NETHERLANDS

Bloemen's excavation was followed with the discovery by

van Giffen in 1935, 1936, and 1937 of a group of settlements

of the first and second centuries A.D. near the

villages of Fochteloo, Rhee, and Sleen; and in 1938, again

near Fochteloo,[123]

of a settlement of the same period which

van Giffen believed to be the farm and residence of a

chieftain (figs. 303-304). This settlement comprised a long

house, protected by fence and ditch, and a nearby hamlet,

likewise fenced in, consisting of three smaller houses and

a couple of open barns. All of these houses were aisled and

were entered broadside by two entrances lying opposite

one another in the middle of the long walls and giving access

to a median crosswalk that separated the stables for the cattle

from the living quarters of the people. The long house of

the chieftain had a third additional entrance at the rear of

the stables, primarily for the use of livestock. This house

was 70 feet long and 21 feet wide (21·40 m. × 6·50 m.).

The great significance of van Giffen's excavations of

Ezinge was that they solved an enigma that had puzzled

students of European house construction for over a century.

They brought to light the prehistoric prototypes of two well-known

and closely related modern house types, namely

that of the Lower Saxon "Wohnstallhaus" and of the

Frisian "los-hus." The oldest surviving specimens of these

two widespread house types date from the early sixteenth

or, at the most, from the end of the fifteenth century.[124]

Van Giffen's excavations demonstrated that this type

was infinitely older than anybody had heretofore presumed

it to be, and their immediate prototypes could now be

traced back as far as the fourth century B.C. It was clearly

only a matter of time for the connecting medieval links to

be found. Once more it fell to van Giffen to lead the way

in this search. A trial ditch run through a Warf in the

vicinity of the village of Leens (Groningen), Holland,

revealed the profiles of a settlement whose life span started

approximately at the point where that of Ezinge ended.

And in a systematic excavation of this Warf conducted in

the subsequent year, van Giffen[125]

could trace his aisled

Iron Age house through seven successive layers from the

end of the seventh century A.D. to the beginning of the

eleventh. Altogether some twenty-three houses came to

light: some of them built with wattle walls, others with

walls of turves; but all of them had their roofs supported by

two rows of freestanding inner posts. I reproduce as a

typical example the plan of a house of Layer B (fig. 305),

after van Giffen, and a cross section of this house (fig. 306),

as suggested by Zippelius.[126]

For Fochteloo, see van Giffen, 1954. For Rhee, Zeijen, and Sleen,

see van Giffen, "Omheinde . . ," 1938; and idem, "Woningsporen . . .,"

1938.

For quick information on these two important house types, see

Hekker, 1957, 216ff, and Haarnagel, 1939.

In the ensuing discussions the basic similarities between van Giffen's

Iron Age houses, on one hand, and that of the Lower Saxon or Frisian

farmhouse on the other, have sometimes been forgotten. Surely enough,

there are distinctive constructional differences, which need not be

dwelt upon here, yet the basic layout and functional use of the house is

identical: three aisles, the center aisle being used as a passage and hearth

place, the aisles serving as shelter for the livestock and sleeping quarters

for the farmer and his family.

HODORF, SCHLESWIG-HOLSTEIN, GERMANY

Van Giffen's work in Holland was only a beginning. In

1936 Werner Haarnagel launched the first of an equally

exciting series of excavations in the adjacent coastlands of

northern Germany, where he discovered a Germanic flatland

farm of the first and second century, near the village

of Hodorf, Schleswig-Holstein, on the banks of the river

Stör, not far from its confluence with the river Elbe.[127]

It

consisted of a three-aisled dwelling with hearth, to which a

one-aisled barn was added axially at a slightly later date

(fig. 307). The construction method employed in this dwelling

was identical, in all details, with those of van Giffen's

houses at Ezinge: six pairs of inner posts serving as principal

roof supports, an outer perimeter of wall posts serving

as footing for the rafters, plus the customary envelope of

wattle walls running in total independence of the supporting

members. The aisles were divided into cattle stalls in the

rearward part of the house, as in Ezinge, except that in

Hodorf this area was entirely matted with wattlework. A

distinctive feature of the Hodorf farm was that its hearth

was framed by four posts which were out of line with the

principal roof supports and also differed from the latter by

being round. They were obviously not part of the regular

structural system. Haarnagel thought that they might have

carried a smoke flue, or that they belonged to a separate

inner armature of poles which carried an elevated section

of the main roof over an opening in the ridge above the

hearth site, serving as light source and as smoke outlet. A

similar arrangement of poles ranged in a square around the

hearth had been observed in other Iron Age houses in

vastly distant places.[128]

Haarnagel has reconstructed the Hodorf house in a handsome

model which is displayed at the Niedersächsische

Landesstelle für Marschen- und Wurtenforschung in the

city of Wilhelmshaven (fig. 308). While many of the details

in the roof section of this model must by necessity remain

conjectural, the concept of the house as a whole is unquestionably

sound. The pottery found in the Hodorf house

indicated as time of occupancy the first and second century

A.D. Toward the close of the second century the site was

imperiled by tidal inundations. Its inhabitants made an

attempt to save the house by filling it up inside with sand,

312. WILHELMSHAVEN-HESSE, GERMANY

EXTERIOR VIEW, AISLED HOUSE, 6TH-9TH CENTURIES

MODEL IN THE NIEDERSÄCHSISCHES LANDESINSTITUT FÜR

MARSCHEN- UND WURTENFORSCHUNG

[after Haarnagel]

The excavation of Warf of Wilhelmshaven-Hesse (trial ditch in

1939 disrupted by World War II, resumed in 1949, continued in

1950) offered the first evidence that the aisled and timbered Iron

Age hall known through the excavations of Hodorf (figs. 307-308)

and Einswarden (fig. 309) continued to be used in the coastlands of

northern Germany in early medieval times. As it was excavated the

Warf revealed, in settlement horizons extending from the 7th through

10th centuries A.D., aisled and bay-divided houses ranging in

length from 39½ to 59 feet, and in width, 17½ to 21 feet.

The house model shown here is a reconstruction of one of the larger

houses of the Warf. Like those of Fochteloo and Einswarden, it had

an axial entrance for cattle in one of the narrow walls and a lateral

entrance to the living area close to the opposite end of the house.

number of posts were reset on this occasion, and the roof

may have been replaced entirely, but in all other respects

the house remained the same, except that now it was used

exclusively as a dwelling. It continued to be used in this

form until the end of the third century when it made room

for a new but smaller house of the same construction type.

As early as 1928 by Gudmund Hatt in an Iron Age house at Kraghede,

Denmark, see Hatt, 1928, 254; in 1932 by F. Bloemen at Wijchen,

Holland, see Bloemen, 1933; and in 1935 by Otto Doppelfeld in NauenBärhorst,

see Doppelfeld, 1937/38, 312. Also see below, 119ff.

EINSWARDEN, GERMANY

The operations at Hodorf had barely been completed, when

in the winter of 1937/38 Haarnagel was called to a site in

the vicinity of the village of Einswarden,[129]

on the left bank

of the estuary of the Weser river, where the heavy machinery

of a modern land improvement project had edged into the

core of an ancient dwelling mound. Systematic excavations

were undertaken in the summer of 1938 but remained confined

to only a small sector of this large mound.

They brought to light three post-and-wattle houses of

the period around the birth of Christ and below these

dwellings, in an even earlier settlement horizon which

reached back to the second and third centuries B.C., four

additional houses of the same type. The largest of the

upper settlement measured 56 feet by 21 feet (17 m. ×

6·5 m.); the smallest, 33 feet by 16 feet (10 m. × 5 m.).

The latter, having its wood work practically intact to a

height of 16 inches (40 cm.), was especially well preserved.

Haarnagel could observe that the outer posts of house II

leaned inward. He assumed that the posts that he found

were the lower portions of rafters that rose from the ground

directly, and reconstructed the house accordingly.[130]

Albert

Genrich[131]

and Zippelius[132]

consider it more likely that these

oblique outer posts were short, that they carried an outer

frame of horizontal poles that served as footing for the

rafters, and leaned inward in order to counteract the outward

thrust of the roof, as shown in figure 309 B.

The excavations of Einswarden are summarized briefly in Haarnagel's

article on the origins of the Lower Saxon farmhouse (1939,

267-71). A systematic excavation report has not come out.

Model reconstruction in the exhibition rooms of the Niedersächsische

Landesstelle für Marschen- und Wurtenforschung in Wilhelmshaven,

Germany. In another reconstruction published in Haarnagel's essay

on the northwest European aisled hall and its development in the North

Sea coastland ("Das nordwesteuropäische . . . ," 1950, 84, fig. 3), Haarnagel

reconstructs the outer posts as long oblique forks that buttress the long

beams that rest on the principal uprights.

AALBURG, NEAR BEFORT, LUXEMBOURG

With the outbreak of World War II, all of this excavation

ceased. Save for an isolated excavation conducted by Gustav

Rieck during the German occupation of Luxembourg at

Aalburg, near Befort,[133]

nothing new was added to our

knowledge of the early history of the three-aisled timber

house. Rieck uncovered the foundations of an aisled timber

hall of extraordinary dimensions (102 feet long and 29 feet

broad [31 m. × 8·8 m.]) which antedated even the earliest

Ezinge houses (figs. 310, 311). Here, it seems, in a dwelling

that had been constructed as early as 500 B.C., in territory

where Celtic and Germanic influences intermingled, the

excavator had come upon a floor plan that anticipated by

one millennium the T-shaped Flet and Dele arrangement

of the Lower Saxon farmhouse. The roof-supporting posts

of this house were not sunk into holes but rose freely from

base blocks above the ground, attesting overhead a solid

frame of cross and long beams. This site raised the interesting

question, whether the aisled West-Germanic timber

house might not have been adopted at a very early date in

the territory of the neighboring Celts.

WILHELMSHAVEN-HESSE, GERMANY

When excavation work could be resumed after the war had

ended, Haarnagel added a number of excavations to his

preceding work, which enabled him to trace the history of

the aisled timber house both further back and further

forward in time. A trial ditch dug in 1939, just as the war

broke out, in Hesse, one of the suburbs of the city of

Wilhelmshaven, had suggested the presence, in a settlement

stratum of the seventh century A.D., of aisled houses of

the Hodorf-Einswarden type, such as he had previously

been able to assert only for the span of 300 B.C. to A.D. 200.

Systematic excavations undertaken in 1949 and continued

in 1950[134]

surpassed all expectations by establishing the

existence of this house type in settlement layers not only of

the seventh, but also of the eighth and ninth centuries A.D.

And in 1951-53 this span was further extended into the

eleventh, the twelfth, and thirteenth centuries through the

excavation of a medieval trading settlement in the city of

Emden.[135]

The result of these excavations is visually summarized

in a reconstruction model of one of the houses of

Wilhelmshaven-Hesse, here shown as figure 312.

JEMGUM, NEAR LEER, GERMANY

Conversely, in an excavation conducted in 1954 Haarnagel

had the good fortune of unearthing in a place called Jemgum

near Leer,[136]

on the left bank of the river Ems, an

aisled house with pottery shards and artifacts ranging from

the beginning of the seventh to the end of the fifth century

B.C. (transition from Bronze Age to Early Iron Age.) The

walls of the Jemgum house (figs. 313-314) were a different

construction type from those of the previously discovered

houses. They were built of horizontal logs of ash, squared

off, and held in place by vertical ash saplings. In the middle

of each long wall there was an entrance protected by a

projecting porch. The roof was carried by four freestanding

inner posts of a diameter of eight inches (20 cm.), dug

sixteen inches (40 cm.) into the ground. The hearth lay in

the middle of the center aisle, in the northeastern half of the

house. On the opposite side of the house the ground was

covered by a wooden floor covering of alder planks, which

suggests that this section of the house was used as a living

and sleeping unit.

On Jemgum, see Haarnagel, 1957, 1-44. The house of Jemgum was

inhabited only by human beings. Other houses of the same construction

type and the same period accommodating men and cattle under the

same roof have in the meantime been unearthed a little farther downstream

on the same bank of the river Ems, in a place called Boomborg/Hatzum;

for a preliminary report on this, see Haarnagel, 1965, 132-64.

FEDDERSEN-WIERDE, NEAR BREMERHAVEN,

GERMANY

Haarnagel's most successful excavation—begun in 1955,

continued every subsequent summer, and still in progress

at the time of this writing—was undertaken on an Iron Age

Warf called Feddersen-Wierde on the right bank of the

river Weser not far from Bremerhaven. As this dwelling

mound was peeled off, layer by layer, it released the remains

of forty-eight houses; the majority were in excellent condition,

reflecting the various stages of growth of a settlement

that had started as a flatland farm at about the time

Christ was born, and was subsequently raised, in seven

stages, to successively higher levels, until around the year

400 it had reached an ultimate height of 13 feet (4 m.)

above its original starting point and a diameter of about

656 feet (200 m.). The results of this extraordinary excavation

are known so far through preliminary reports only.[137]

In figure 315 I reproduce a plan of settlement period IIB,

which shows the Warf in the stage it had reached sometime

during the first century. At this time the settlement consisted

of a principal Warf and a secondary smaller Warf,

both protected by a peripheral ditch. The principal Warf,

some 295 feet long and 98 feet wide (90 m. × 30 m.),

accommodated a cluster of four houses; the smaller, a

cluster of only two. The houses varied considerably in

size, the largest measuring 97 feet by 21 feet (29·50 m. ×

6·75 m.); the smallest, 33 feet by 16 feet (10·00 m. ×

5·00 m.) Each house formed a self-sufficient agricultural

entity, combining under one roof the living quarters of its

owner and the stables for his livestock (fig. 316). The hay

and harvest was stored in separate open sheds to the side of

the house. The layout of the main houses is identical with

that of the contemporaneous houses that van Giffen had

encountered at Fochteloo (figs. 303-304). Like them, the

houses of the Feddersen-Wierde had their principal entrance

arranged in opposite pairs in the long walls, giving

access to a crosswalk which separated the quarters of the

humans from those of the animals. In the smaller houses

where the areas of living quarters of the owner and the

stables for his livestock were more or less equal, this led to

a fairly balanced arrangement with the entrances often

exactly in the center. But in the houses of the leading

families, superior wealth in cattle led to an elongation of the

stables and to the addition in the latter of a subsidiary

C. ELEVATION

principal members only, shown; for more complete

assembly see exterior view on next page.

B. CROSS SECTION

A. PLAN

detail of plan at jamb of doorway

313.A. B, C

JEMGUM, LEER, GERMANY

AISLED HOUSE, 7TH-5TH CENTURIES B.C.

[redrawn from W. Haarnagel, 1957, 21, Plan. No. 7]

The site is on the left bank of the estuary of the river Ems. The house was small, no more than 15 feet wide and 25 feet long. It was used

exclusively as a dwelling and gave no evidence of ever having sheltered animals. In the middle of each long wall, slightly off center, were

opposing entrances protected by projecting porches.

The roof was carried by two pair of inner posts (unscantled oak trunks, dia. 20cm) dividing the house into a central area of roughly 6½ × 13

feet asymmetrically placed, and with aisles all round it. The hearth lay in the axis of this center space, in the western half of the house which

had a simple clay floor and must have served as kitchen.

The floor of the space between the eastern pair of posts and the eastern end wall was covered with wooden planks cut from alder trees; this

area, better insulated from dampness than any other in the house, must have served as living and sleeping quarters. All structural members of

the dwelling that were posted into the ground, or that lay atop the ground, were found to be in good condition, many of the boards forming the

wooden floor of the presumed sleeping area were still in place.

314. EXTERIOR VIEW

JEMGUM, LEER, GERMANY

AISLED HOUSE, 7TH-5TH CENTURIES B.C. [redrawn from W. Haarnagel]

Drawings and models are in the Niedersächsisches Landesinstitut für Marschen- und Wurtenforschung

The walls of the house were made of squared ash logs, of which the bottom course was still well preserved. They were held in place at distances

varying between 5 and 6½ feet, by paired saplings pointed and driven into the ground to a depth of about 2 feet, with five pairs in each long

wall, and three in each end wall. At their meeting points in the corners of the house, the ash logs had rotted away, and for that reason, it could

not be ascertained in what manner they were jointed. It seems reasonable to assume that they were notched into each other at right angles,

since otherwise these timbers would have been subject to displacement from the thrust of the rafters.

Since the free-standing inner posts were only set 15¾ inches into the ground, they must have been framed crosswise at their heads by tie beams,

and lengthwise by longitudinal plates serving as footing for the rafters, or supporting them in midspan. There were no roof-supporting posts in

the end walls, indicating that the roof was probably hipped over the building's narrow ends. The construction of the walls, although common in

heavily wooded areas of Scandinavia and Alpine regions, is atypical for this part of Europe.

315. FEDDERSEN-WIERDE. PLAN [after Haarnagel, 1957, fig. 2]

AISLED HOUSES OF WARF-LAYER II B, 1ST-2ND CENTURIES

Haarnagel's exploration of this Warf, conducted from 1955 onward under the auspices of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, was the

German counterpart to van Giffen's excavation of the Warf of Ezinge (figs. 292-99). The site, on the right bank of the estuary of the Weser,

was carefully selected after many sample drillings from a chain of nine dwelling mounds running in an almost straight line south to north over a

distance of 15 kilometers. The Warf encompassed seven settlement horizons, a new one every 50-80 years, to compensate for the steadily rising

innundation level.

The earliest settlement was a flatland farm built around the birth of Christ. The Warf was abandoned around 400 A.D. when it had reached

a height of about 13 feet (4m). The dwellings buried in its various layers were as well preserved as those of Ezinge and for the same reasons

(see caption, fig. 299); and were of the same construction type. The plan above shows the Warf in the stage it had reached toward the end of

the first century A.D.

FEDDERSEN-WIERDE, NEAR BREMERHAVEN, GERMANY

316.B AUTHORS' RECONSTRUCTION (DRAWN BY WALTER SCHWARZ)

SEE FIGURE 175. PAGE 216, VOL. 1, FOR A LARGER INTERPRETATION OF THIS DRAWING

316.A PLAN [after Haarnagel, 1956, Pl. 3]

AISLED HOUSE OF A CHIEFTAIN, Warf-LAYER II B, 1ST-2ND CENTURIES

With the cattle barn of Ezinge (figs. 298-99) this is one of the finest examples of a house type widely diffused in the Germanic territories of

Holland and Northern Germany during the first millenium B.C. and throughout the entire Middle Ages. The house was 97 feet long (28.50m)

and 21 feet wide (6.75m). It combined under one roof the owner's living quarters and the stables for his livestock. In the area used by animals

(eastern 52½ feet of the house) the roof-supporting trusses were more narrowly spaced, leaving in the aisles between each pair of posts a stall

for two head of cattle (32 head altogether).

As in the chieftain's house at Fochteloo (fig. 304) stables and living area were separated by an entrance bay accessible through doors in the long

walls, while animals entered through a gate in the eastern end wall. The walls and all the internal cross partitions were done in wattlework,

daubed with manure. The stable area had the traditional mats of wattlework on which the manure was gathered, with cess trenches beneath to

allow for drainage. The walk between these mats was paved with turves laid between floor beams running parallel with the trenches.

318.A, C, D. NAUEN-BÄRHORST[138]

, MIGRATION PERIOD VILLAGE, 2ND-3RD CENTURIES A.D. [redrawn freely

after Doppelfeld, 1937-38, 297, fig. 10].

318.B. LEIGH COURT[139]

, about 1325 ± 30 years

318.C WOVEN WATTLEWORK. INFILL BETWEEN POSTS

INFILL BETWEEN SLOTTED POSTS

318.A VERTICAL BOARDS

BETWEEN SLOTTED POSTS

318.D HORIZONTAL BOARDS. LOWER EDGE SLOTTED

SET BETWEEN SLOTTED POSTS

318.B WOVEN WATTLEWORK. MEDIEVAL

CLEFT STAVES & SLITHERS (SLATS)

VARIOUS TYPES OF WALL CONSTRUCTION

Imprints of rods and boards in lumps of clay that were part of the original daubing of the walls offered evidence for the existence of several types of wall

construction. Wattlework was in the minority, generally used as infilling between posts (as in figs. 301-302); it was not a load-bearing structural feature.

Of the boards above, it is not certain whether A was set horizontally or vertically; D would have been used only horizontally, with the groove downward.

Braiding walls from thin strips of oak (B) is a technique well known from later medieval buildings (see Charles and Horn, 1973, 20-21, figs. 21 and 23).

317. FEDDERSEN-WIERDE, NEAR BREMERHAVEN, GERMANY

HOUSE OF THE EARLIEST SETTLEMENT HORIZON. DETAIL

[photograph by courtesy of W. Haarnagel]

These are remains of two of the principal roof-supporting posts of the house, for which the builder used the round trunks of relatively young

and slender oaks without debarking them. The superb state of preservation of both timbers and the wattlework of which the walls and cross

partitions in the aisles were formed owes to the fact that whenever a house was abandoned because of floods and then rebuilt on higher ground,

its remains were soon covered by layers of fine silt deposited during floods, thus sealing its contents against air and bacterial decay.

attained the distinctive T-shaped floor plan which later

became the hallmark of the Lower Saxon farmhouse. The

long house in the northwest corner of the main Warf of

settlement period II-B of the Feddersen-Wierde is one of

the finest of this type of Iron Age house known to date. In

figure 316A I reproduce its plan, after Haarnagel, and in

figure 316B a tentative reconstruction of my own. The excavation

photo shown in figure 317 of one of the cattle boxes

of house I of the oldest settlement horizon of Feddersen-Wierde,

gives an idea of the magnificent state of preservation

in which the walls and roof-supporting posts of some

of the older houses of this site were found.

The occupants of settlement-horizon II of the Warf

Feddersen-Wierde were field-ploughing and cattle-raising

farmers. In settlement-horizon III (first to second century

A.D.) the economy, and with it the entire social structure of

the village, begins to change. The dominant architectural

feature now, as well as in all the subsequent horizons (IV,

V, VI, and VII, ranging from the third into the fifth

century A.D.), is a large aisled hall (without stalls for cattle

and carefully fenced in), used as the residence of a person

of conspicuous wealth and prominence. Next to this hall is

a second hall (likewise without cattle stalls) which Haarnagel

believes was used as an assembly place for the entire

community. Animal husbandry and agriculture give way

to industry and trade, and the growth of a new class of

workmen who lived in smaller houses and worked in the

service of their trading chieftain.

ELISENHOF, NEAR TÖNNING, SCHLESWIG, GERMANY

319.

320.

AISLED HOUSE, 9TH CENTURY A.D. [excavation photos courtesy of A. Bantelmann]

The overview (fig. 319) of the Warf shows the remains of the houses; below (fig. 320), the detail shows a portion of the wattled walls of the

house with inclined posts carrying a peripheral course of poles on which the rafters were footed.

The great historical significance of the excavation of this Warf is that it closed the gap between the Iron Age and Migration Period houses

(shown in figs. 293-318) and their medieval derivatives (figs. 339-354). The settlement was started on flatland in the 7th century; its subsequent

development could be traced clear into the 11th century. In layout and construction its houses were virtually identical with those of Ezinge

(figs. 293-299), and Feddersen-Wierde (figs. 316-317). They were in some places preserved to a height of 7 feet.

321. ANTWERP, BELGIUM. UNAISLED AND AISLED HOUSES

PLANS, EARLY 11TH CENTURY A.D.

[after A. Van de Walle, 1961, 128, fig. 35]

The house plans and reconstruction shown here and in fig. 322 are in themselves of no particular architectural distinction. But they do mark the

historical point at which the aisled and bay-divided timber house, the premedieval history of which has been briefly traced in these pages,

attempted to gain a hold in the new and rapidly developing medieval cities.

Excavations conducted in 1955-1957, in what was then the old city of Antwerp (and is now the center of the modern town) brought to light

three medieval habitation levels in an average depth of 5 to 7 feet (1.50-3.50m) beneath the present street level. By pottery and other artifacts

these strata could be dated: the lowest to about 850-976, the middle to about 976-1063, and the top level to 1063-1225. On each horizon the

excavator found three houses in a row, side by side, gable walls facing the street. The houses shown here belong to the middle level. The larger

one to the right is aisled; the others, narrower and shorter, are unaisled. These two are divided internally into a main hall with hearth, and with

one or more partitions to the rear perhaps serving as private or storage rooms.

Aisled houses were well suited to the open terrain of the nonurban countryside. But in the densely built cities, with open land at a premium, the

aisled structure of one story had limited utility and future. Some wealthy individuals or institutions could, to be sure, acquire enough urban land

upon which to build expansive aisled houses on one level, and could afford the expense of their maintenance. Such was the case with ecclesiastical

overlords (see figs. 339-340) or corporate bodies such as the Church (figs. 341-343) or the guilds. But for the most part, aisled dwellings were

impractical in, and proved antithetical to the function of the city. The type came to be replaced by narrower structures of multiple stories

providing space above ground level, set with gable walls toward the street and side walls almost touching, a picturesque and early characteristic

of new urban architecture.

322. ANTWERP, BELGIUM

AISLED HOUSE, EARLY 11TH CENTURY

[the reconstruction illustrated is redrawn from A. van de Walle, 1961, 129, FIG. 36]

This isometric rendering, conjectural in detail yet fairly

certain in general lines, illustrates more persuasively than

the plans of the preceding figure why it was that aisled

houses could not survive the pressures of dense urban

development. The low, aisled house of the open country, in

the struggle to adapt it to urban row-house conditions,

soon proved to be a wasteful use of costly and limited

city space. Therefore this house type was, in the cities

quickly discarded.

In process of adaptation, the remaining nave (after

aisles were eliminated) could, to be sure, have been raised;

but the skeletal construction of the old northwest European

all-purpose house was never intended to bear the load

of superincumbent stories. A new type of timber framing

with strong load-bearing walls evolved to make timber

framing possible in construction of narrow urban houses.

But because of its total vulnerability to fire, the timber

house eventually came to give way, as the cities grew, to

masonry houses.

BÄRHORST, NEAR NAUEN, GERMANY

To the successful excavation work by van Giffen and

Haarnagel in the coastlands of Holland and northwestern

Germany, one has to add the work of others. As early as

1935-37 Otto Doppelfeld had unearthed a palisaded village

of an estimated fifty aisled houses, on the Bärhorst,[140]

a

shallow, sandy plateau in a marshy swale near Nauen

(Berlin). The site had been discovered in the course of

trenching operations undertaken before the installation of

a giant sewage disposal plant. Remnants of pottery and

other cultural accessories showed that the village was

constructed around A.D. 250 and that it was held in occupancy

for about a century. Since it lay in an environment

that was utterly unsuited for successful agricultural exploitation

and perished in a fire that seems to have been

associated with a planned and systematic abandonment (no

objects of any use were left), Doppelfeld concluded that it

might have been the temporary site of a wandering Germanic

tribe who discarded the site when they found prospects

for the conquest of more suitable land. While basically

adhering to the same construction type, the Bärhorst houses

showed a great variability in the treatment of their walls

(fig. 318). Some of the houses had simple wattle walls; in

others the walls were formed by boards mounted horizontally

or vertically between the wall posts. Still others

were braided from thin split pieces of straight wood (leftovers

from the hewing of the structural timbers). The

Bärhorst village showed that the aisled pre-medieval timber

house extended into the third and fourth century A.D. eastward

as far as the longitude of the modern city of Berlin.

TOFTING AND ELISENHOF, NEAR TÖNNING,

SCHLESWIG-HOLSTEIN, GERMANY

Albert Bantelmann, on the other hand, pressed the search

northward by excavating, in the summers of 1949 and 1950,

a dwelling mound at Tofting (Schleswig-Holstein)[141]

at the

mouth of the river Eider, close by the Danish border. His

excavations showed that conditions in the homeland of the

Anglo-Saxons were identical with those which van Giffen

and Haarnagel had found prevalent in the adjacent territories

of the Frisians.

Tofting was a relatively modest site; but from 1957

onward, in annual excavations as yet not terminated,

Bantelmann peeled off, layer by layer, in the Warf Elisenhof,[142]

near the town of Tönning at the mouth of the

river Eider in Schleswig, the remains of a village that was

founded in the seventh or eighth century A.D. and remained

in continuous occupation deep into the High Middle Ages.

The earliest settlement, which is so far known only AISLED LONG HOUSE OF A BRONZE AGE SETTLEMENT PLAN [after H. T. Waterbolk, 1964, fig. 5] Entered through two transeptal porches leading to a central entry way, this dwelling From the outside this house must have been very similar in appearance to the two

through a preliminary report, was built on natural ground

on one of the banks of the river Eider. Later the site was

raised and peripherally expanded by heavy deposits of

manure and clay, until it finally comprised an area of

roughly seven hectares. The occupants of the earliest settlement

were cattle-raising farmers, which is attested by the

323. ELP, PARISH OF WESTERBORK

DRENTHE, THE NETHERLANDS

ABOUT 1250 B.C.

was divided by it into halves, one for dwelling and the other for stabling livestock, a

distinction that became traditional.

longhouses of Warendorf (figs. 326. E-F), nearly 2,000 years its junior. In the

dwelling portion, inner and outer posts were carefully aligned to form a widely spaced,

strong sequence of roof-supporting trusses. In the stable half posting was lighter,

closer, and the posts probably served as dividers for the stalls.

CHEDDAR, SOMERSET, ENGLAND

AISLED PALACE HALLS, 12TH & 13TH CENT.

[courtesy of P. Rahtz, and Ministry of Building and Works, Crown

Copyright]

324.A

The composite plan shows the layout of East Halls I, II, and III. The original ten-bay

building dates to the early 12th century. It was replaced 100 years later by a smaller

six-bay hall 71 feet by 48 feet. At this time the roof supports were set into new square

post holes, some of which overlapped the round ones of the original hall. Toward the

end of the 13th century the second hall was replaced by a third of yet smaller size

66 by 42 feet) and without aisles.

324.B

At the time of Henry I (1100-1135) the hall was an aisled, ten-bay structure, 110 feet

long and 54 feet wide. The course of the outer walls could be identified by large post

holes, at 8-foot intervals, linked by ground timbers. The roof-supporting posts were

apparently rough-scantled logs over 15 inches in diameter, set into round post holes

packed with gravel.

in, respectively, decreasing magnitude. The predominant