The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V.1.1.. |

| V.1.2. |

| V.1.3. |

| V.1.4. |

| V. 2. |

| V.2.1. |

| 10. |

| 10. |

| V.2.2. |

| V. 3. |

| V.3.1. |

| V.3.2. |

| V.3.3. |

| V. 4. |

| V.4.1. |

| V.4.2. |

| V.4.3. |

| V. 5. |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

| V. 6. |

| V.6.1. |

| V.6.2. |

| V.6.3. |

| V.6.4. |

| V. 7. |

| V.7.1. |

| V.7.2. |

| V.7.3. |

| V.7.4. |

| V.7.5. |

| V.7.6. |

| V. 8. |

| V.8.1. |

| V.8.2. |

| V.8.3. |

| V.8.4. |

| V.8.5. |

| V.8.6. |

| V.8.7. |

| V.8.8. |

| V. 9. |

| V.9.1. |

| V.9.2. |

| V.9.3. |

| V. 10. |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. |

| V. 11. |

| V.11.1. |

| V.11.2. |

| V.11.3. |

| V. 12. |

| V.12.1. |

| V.12.2. |

| V.12.3. |

| V. 13. |

| V.13.1. |

| V.13.2. |

| V. 14. |

| V.14.1. |

| V.14.2. |

| V. 15. |

| V.15.1. |

| V.15.2. |

| V.15.3. |

| V.15.4. |

| V. 16. |

| V.16.1. |

| V.16.2. |

| V.16.3. |

| V.16.4. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. | V. 18 |

| V.18.1. |

| V.18.2. |

| V.18.3. |

| V.18.4. |

| V.18.5. |

| VI. |

| VI. 1. |

| VI.I.I. |

| VI.1.2. |

| VI.1.3. |

| VI.1.4. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI.2.1. |

| VI.2.2. |

| VI.2.3. |

| VI.2.4. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI.3.1. |

| VI.3.2. |

| VI.3.3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI.4.1. |

| VI.4.2. |

| VI.4.3. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

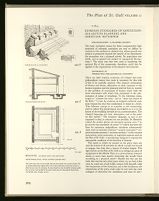

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V. 18

SANITARY FACILITIES

V.18.1

CLEANLINESS AND GODLINESS

A word must be said about the contrivances which in both

medieval and modern Anglo Saxon literature are referred

to with the evasive designations "garderobe," "privy," or

"rere-dorter,"[655]

and in the explanatory titles of the Plan

of St. Gall are varyingly designated as exitus, exitus necessarius,

necessariū, and requisitum naturae. On first inspection

the subject is somewhat bewildering, since in certain areas

of the Plan provisions for this facility are made with a

profuseness that exceeds any comparable modern standards

of hygiene, while in others they appear to be wholly

overlooked.

A more judicious examination discloses that the measure

of attention lavished on the privies by the designer of the

Plan of St. Gall is directly related to the rank or administrative

status that their beneficiaries hold in the monastic

polity. The subject has both social and philosophical implications

and throws some light upon the history of western

hygiene.

V.18.2

TWO BASIC TYPES OF PRIVIES

INDIVIDUAL PRIVIES

Individual privies directly attached to the house or an

apartment, containing either one or more toilet seats, are

at the disposition of visiting noblemen (fig. 495A) and those

monastic functionaries who, because of their specific responsibilities,

must live in separate quarters outside the

claustrum, viz., the Porter (fig. 495B), the master of the

Outer School (fig. 495B), the master of the novices,

(fig. 495C), the chief physician (fig. 495D). They are

also installed for small groups of regular monks who are

not part of the monastic community, such as the visiting

monks (fig. 495E), and those being segregated for health

reasons, such as the sick novices (fig. 495C) or the acutely

ill patients in the House of the Physicians (fig. 495D).

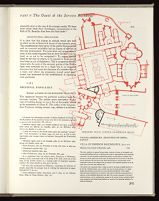

COMMUNAL PRIVIES

Apart from these private toilets directly attached to the

bedrooms of their respective users, there are others installed

in greater quantities in separate outhouses located

directly behind the buildings they serve. The largest

among these is the privy for the servants at the House for

Distinguished Guests (fig. 496A). It is 10 feet wide, 45

feet long, and contains eighteen toilet seats. Next in size

is the privy for the students of the Outer School, which

seats (fig. 496B). Then follows in order of decreasing magnitude:

the privy of the House for Bloodletting, with seven

seats (fig. 496C); the privy of the Abbot's House, with six

seats (fig. 496D); and the privies of the Novitiate and the

Infirmary, each with six seats (fig. 496E). The Monks'

Privy (fig. 497) falls into a category by itself; like the other

collective privies of the Plan, it is a separate house, but it

does not have their narrow, elongated floor plan; instead, it

is almost square. It measures 30 feet by 40 feet, provides

for a total of nine seats (sedilia), a stand for a lantern

(lucerna), and three other facilities of oblong shape, whose

function remains unexplained.

DIFFERENT ORIGINS

The small individual privies of the distinguished guests

and the higher monastic officials (fig. 495, A-E) doubtlessly,

have their prototypes in the vernacular architecture of the

upper strata of Carolingian society. The longhouse for the

servants of the distinguished guests, the students of the

Outer School, and other smaller monastic groups (figs.

496, A-E), I would be inclined to derive from Roman and

medieval military architecture, although I cannot support

this hypothesis with any tangible archaeological evidence.

The square shape of the Monk's Privy is somewhat reminiscent

of that of the Roman public latrine, but may

actually not be in any ancestral relation to the latter, and

may owe its squarish shape to the desire to add to the single

row of toilet seats such other facilities as a urinal or troughs

with water for washing hands.

V.18.3

SANITARY FACILITIES OF THE PLAN

IN THE LIGHT OF ANCIENT

AND MODERN STANDARDS OF HYGIENE

The sanitary installations of the Plan of St. Gall raise the

interesting question of environmental hygiene in a planned

medieval community of men that can be placed into proper

historical perspective only if analyzed in comparison with

ancient and modern facilities of this type.

THE PUBLIC ROMAN LATRINE

The public Roman latrine consisted of a large space, PRIVIES CONSTRUCTED AS SEPARATE HOUSES CONNECTED

usually square (fig. 499) but often trapezoidal or semicircular

(fig. 500A), or a combination of such shapes (fig.

500B). The seats were ranged along the walls all around

the periphery of the building, leaving everyone fully

exposed to the view of the others, with sufficient floor

space in between for people to congregate in amicable

conversation. Channels beneath the seats, flushed by running

water diverted from the aqueducts, drained into the

public sewer system. The seating capacity of these buildings

could attain substantial proportions. The gymnasium of the

city of Philippi had a latrine with fifty seats. In the market

of Miletus there was one with forty (fig. 499A-B); in the

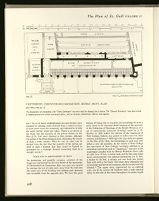

496. PLAN OF ST. GALL

WITH THE BUILDINGS THEY SERVE BY COVERED PASSAGES

497. PLAN OF ST. GALL

MONKS' PRIVY

Comparison with later monastic architecture (figs. 501-503 and 516-520)

suggests that the Monks' Privy was level with the Dormitory, a relationship we

misinterpreted in the Aachen model of the Plan in 1965, and have corrected

here. Waste was either to accumulate in a cesspool at ground level, later to be

used as fertilizer in the garden nearby; or, less likely, flushed away by a water

channel.

The Privy is 30 feet wide, 40 feet long (12 modules wide by 16 long) and has

9 toilet seats and 3 stands serving as urinals or washbasins. In these measurements,

multiples of 3, 4, and 10 may indicate the pervasiveness of the concept of

sacred numbers even in so humble a facility.

had settled this public need with the same flair with

which they engineered a world-wide system of roads, constructed

their aqueducts, and installed grandiose systems

for metropolitan sewage disposal—engineering feats so

great and new in concept that the Greek philosopher

Strabo (b. 63 B.C.) could remark that "if the Greeks had the

repute of aiming most happily in the founding of cities, in

that they aimed at beauty, strength of position, and the

availability of harbours and productive soil, the Romans

had the best foresight in . . . the construction of roads and

aqueducts, and of sewers that could wash out the filth of the

city into the Tiber."[657]

Yet as magnificent as all this appears on first sight, in

terms of effective environmental hygiene, it was far from

providing a satisfactory solution to the sewage disposal

needed in the larger Roman cities. Besides the public

latrines, only the houses of the patricians were linked to the

metropolitan water system. The inhabitants of the tenements,

where the remaining two million Romans lived, had

to carry their domestic ordure in pots to a sewage vat under

the stairwell, bring it to nearby cesspits (with which Rome

was riddled), or take recourse to the even more primitive

method of simply dumping their offal from the windows

into the street. Much of Rome wallowed in filth.[658]

For succinct and colorful reviews of these conditions, see Carcopino,

1960, 39ff; and Mumford, 1961, 214ff.

RATIO OF TOILET SEATS TO NUMBER OF USERS

On the Plan of St. Gall

If one analyzes on the Plan of St. Gall the ratio between

the number of toilet seats provided for the disposal of

human waste and the number of potential users, one

arrives at the startling conclusion that the standards of

sanitary hygiene in a medieval monastery of the time of

Louis the Pious were far advanced not only over those of

any of their classical proto- or antitypes, but—with the

sole exception of modern de luxe hotels—even conspicuously

superior to common standards of modern sanitation.

The House for Distinguished Guests, as we saw, had

bedding facilities for eight noblemen and eighteen servants.

Since the bedrooms for the noblemen were equipped with

their own privies, the eighteen seats of the outhouse must

have been the reserve of the eighteen servants.[659]

They were

set up at a ratio of 1:1. On the level of the court this appears

to have been the norm. The royal guesthouse of the

monastery of Cluny, a facility which was designed for the

accommodation of seventy guests, was furnished with the

same number of toilet seats.[660]

The Outer School of the

Plan of St. Gall, designed for an occupancy of probably

twenty-four students, has an outhouse equipped with fifteen

seats (fig. 496B),[661]

which yields a ratio of 1:1.6. The

House for Bloodletting, probably never occupied simultaneously

by more than twelve monks,[662]

has seven seats (fig.

496C); it therefore had a probable ratio of 1:1.7. The

Abbot's House with a bedding capacity of eight[663]

has six

toilet seats (fig. 496D), yielding a ratio of 1:1.3. And the

dormitories of the Novitiate and the Infirmary, each of

which appear to have been designed for an occupancy of

twelve persons,[664]

are provided with an outhouse equipped

with six seats, corresponding to a ratio of 1:2.

In modern building codes

To place these figures into proper perspective from the

point of view of environmental sanitation, it may be pointed

out that the latest U.S. Army Field Manual 21-10 on

Military Sanitation prescribes eight toilet seats for every

100 men.[665]

In World War II, it was ten seats for every

200 men.[666]

The Uniform Housing Code of 1961 in section

H 505 recommends for hotels one toilet seat per ten

guests;[667]

and the California Administrative Code, Title 17,

as of 1966 stipulates that in camps, toilets should be provided

at the ratio of one toilet seat per fifteen occupants of

the camp.[668]

The luxury of modern hotels, where each

498. OSTIA. ROMAN PUBLIC LATRINE (4TH CENT. A.D.)

This latrine, part of a larger campaign, was built when the forum baths of Ostia were restored in the 4th century. It is among the best preserved

Roman latrines. Facilities of this type, preceded by a vestibule and entered, as here, by a revolving door were by preference built near the forum

or near baths. This latrine had seats of marble over a water-flushed channel.

In private Roman homes the privy was always next to or in the kitchen, making it possible for one drainage ditch to service both, and the bath

as well. Movable receptacles were often installed beneath chairs and placed in the street at night, the waste to be collected by the CONDUCTOR

FORICORUM. Amphoras serving as public urinals were posted by the fullers throughout the streets; their content was used in the process of

cleaning cloth.

toilet, is of relatively recent date. Even today in the majority

of smaller European hotels an entire floor is served by a

single privy at the end of the corridor. The ratio between

available seats and their potential occupants varies anywhere

between 1:10 to 1:30. In the light of these statistics,

the hygiene of the monastery shown on the Plan of St. Gall

must be proclaimed to be superior to that prevailing under

average conditions in most Western countries today. They

fall short only if measured against conditions prevalent in

the most elegant, modern hotels.

The most conservative arrangement on the Plan of St.

Gall is the privy of the regular monks, which is furnished

with nine toilets serving a total of seventy-seven monks,

thus yielding a ratio of 1:8.5. Yet even this is still considerably

more generous than the ratio of 1:12 stipulated today

in the sanitary code of the U.S. Army.

MILETOS, ASIA MINOR, WEST COAST NEAR SAMOS

499.B PERSPECTIVE, CUTAWAY

499.C TRANSVERSE SECTION

499.A PLAN

NORTH MARKET HALL. PUBLIC LATRINE (3rd-4th cent.)

The latrine seats were cut into marble slabs and were placed over a water channel. The

44 keyhole-shaped seats aligned with a slot in the vertical face of the bank of seats to

allow the user access for cleansing. An open channel cut into the slightly slanting marble

floor in front of and parallel to the seats carried water for cleansing the hands (after

von Gerkan, 1922, 18, figs., 20-21).

United States Army, Medical Department, Preventive Medicine

in World War II, II: Environmental Hygiene, Office of the Surgeon

General (Washington, D.C., 1955), 149.

Uniform Housing Code, published by the International Conference

of Building Officials (Los Angeles, 1961), Section H 505.

California Administrative Code, Title 17, Public Health, State of

California Documents Section (Sacramento, 1966), 597.

V.18.4

SUPERIOR STANDARDS OF SANITATION:

COLLECTIVE PLANNING AND

CHRISTIAN RETICENCE

THE MONASTERY: A PLANNED SOCIETY

The basic ecological reason for these comparatively high

standards of monastic sanitation are easy to define: in

contrast to the medieval or classical city, whose growth was

subject to pressures beyond the control of its inhabitants,

the monastery was a planned society. Its population was

stable, and in general not subject to unexpected fluctuations.[669]

The same care that was used in regulating the

spiritual life of the community, therefore, could also be

applied to the organization of its physical environment.

Compare the interesting remarks of Abbot Adalhard of Corbie on

the fluctuation of the number of men to be fed in his monastery, quoted

I, 342-43; and translation, III, 106-107.

DIFFERENCE IN

UNDERLYING PHILOSOPHICAL CONCEPTS

There are other reasons, moreover, of a deeper and more

philosophical nature that made it necessary for this side

of life to be carefully ordered. The classical civilizations

of Greece and Rome, affirmative in their response to the

human organism and the pleasures derived from it, reacted

to the problem of evacuation of human waste with the

same naturalness with which they responded to the phenomenon

of eating or breathing. To the Christian mind,

taught to "chastise the body" and to "deny the desires of

the flesh,"[670]

it was, by contrast, an indignity inflicted upon

man because his soul was condemned to reside in a body.

This different concept is as manifest in the terminology

used to define this physiological inevitability as it is in the

layout of the building devised for its accommodation. The

classical languages are clear, descriptive, and to the point

on this matter.[671]

The monastic language, as one is not

surprised to find, is reticent but not prudish. St. Benedict

coined the evasive phrase ad necessaria naturae exire ("to

go out for the necessities of nature")[672]

which becomes the

base for numerous insignificant variations subsequently

used, such as necessitas fratrum,[673]

corporis necessaria,[674]

corporea

necessitas naturae,[675]

necessitas naturae;[676]

or the variants

necessarium, exitus necessarius, or requisitum naturae used on

the Plan of St. Gall—a terminology designed to express the

inescapable condition of the function it denotes.

The needs to which he attends in the privy were not

only the lowest of all activities in which a monk was bound

to engage, but were also a source of mortal danger. The

light shown on the Plan of St. Gall as an obligatory piece of

equipment in the Monks' Privy is a precautionary measure

aimed at more than merely protecting the monks from

stumbling in a physical sense.[677]

Besides his bed and his

bath, this was the only other place where, by no fault of his

own, he could not avoid bodily contact with himself. Like

the temptations of the dormitory and of the bathhouse, the

temptations of the privy could only be met with the most

stringent of directives for conditions and time of use—

more about these from Carolingian commentaries to the

Rule of St. Benedict than from the Rule itself.[678]

Benedicti regula, chap. 4.11 (corpus castigare) and chap. 4.59 (desideria

carnis non efficere), ed. Hanslik, 1960, 30; ed. McCann, 1963,

26-27; ed. Steidle, 110 and 113.

I refer the reader to the words listed under the headings "urinate"

and "void excrements" in Buck, 1949, 273 and 275, as well as their

equivalents and variants listed in Schmidt, Synonymik der Griechischen

Sprache.

Benedicti regula, chap. 8, ed. Hanslik, 1960, 53; ed. McCann, 1963,

48-49; ed. Steidle, 1945, 145.

It is significant that the reform abbot, Ruodman of Reichenau,

during a secret nocturnal visit to the abbey of St. Gall, chose one of the

seats of the monks' latrine as a vantage point of improper monastic

conduct. For more details on this see I, 261-62.

Cf. the rules mentioned by Hildemar, concerning the behavior of

monks, especially the younger ones, in visiting the necessarium by night,

discussed in I, 252-53.

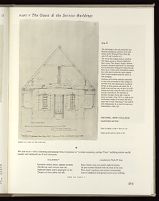

ARCHITECTURAL IMPLICATIONS

It is clear that this change in attitude would also have

its effect on the architectural layout of the monastic privy.

The amphitheater-style layout of the public Roman latrine

with its convivial sociability had no chance of survival in

this new environment. The prescribed and proper deportment

of the monk required that he draw his cowl over his

head, so as not to be recognized.[679]

To expose himself

freely to the view of others, or be exposed to theirs, would

have been an act of blasphemy. This is unquestionably the

reason why the seats of the monastic privies of the Middle

Ages were stretched out in a single line in an elongated

structure that had more the character of a corridor than of

a room, and where any propensity toward social intercourse

was frustrated by the establishment of separating

cross partitions.

Usus antiquiores ordinis cisterciensis, part I, chap. 72, ed. Julianus

Paris, 1664; ed. Hugo Séjalon, 1892, 172.

V.18.5

MEDIEVAL PARALLELS

MONKS' LATRINE IN THE MONASTERY OF CLUNY II

The longhouse became the preferred medieval form for

monastic latrines. The earliest prose description of this

type of building known to me is that of the monks' latrine

in the monastery of Cluny II. The author of the Consuetudines

Farfenses, writing around 1043, defines it as follows:

500. PIAZZA ARMERINA. PROVINCE OF ENNA,

SICILY

VILLA OF EMPEROR MAXIMIANUS, †310 A.D.

[Redrawn from Gentili & Bandinelli, 1956]

1:600

The villa, probably an imperial hunting lodge, consisted of clusters of rectangular and

curved-wall buildings laid out on shifting axes around a large galleried court containing

a fountain. Its most prominent architectural features are the emperor's audience hall

(BASILICA) at the eastern end of the court, his dining hall (TRICLINIUM) to the north,

and an elaborate cold and warm water bath (FRIGIDARIUM, TEPIDARIUM) at the

southeastern corner of the complex near its entrance. The residential quarters lay to the

south side of the court and audience hall.

The latrines were judiciously sited: a large one next to the baths, probably the first to

be used by returning hunters, and a smaller one near the living quarters, in a wedge-shaped

space between QUADRIPORTICUS and thermal installations. Their amphitheatrical

layout allowed users to attend to their needs in full view of everyone else—a

reflection of the unihibited affirmation with which the ancients responded to the body's

natural functions, and an attitude quite opposed to the reticent privacy and hierarchical

social segregation with which these facilities are treated in the repressing ambience of a

medieval monastery.

501. CLUNY II. MONKS' PRIVY (ODILO'S MONASTERY, 994-1049). PLAN

AFTER DESCRIPTION IN THE CONSUETUDINES FARFENSES

The location of the latrine at Cluny is ascertained by excavation of its foundations. It lay at right angles to the monks' dormitory at a distance

of about 1·50m from it, and was accessible through its southern gable wall by a connecting bridge at dormitory level. The dormitory itself

occupied the upper level of a long structure that bounded the claustral complex to the east. For more detail, see Conant's reconstruction of the

layout of Cluny II shown in fig. 515, and his description of Odilo's work in Conant, 1968, 59-67.

"The latrine of the monks is 70 feet long, 23 feet wide. In

the building there have been arranged 45 seats with a small

window above each seat, 2 feet high, 1½ feet wide. Above

these are wooden structures, and above this wooden construction

there are seventeen windows, 3 feet high, 1½ feet

wide" (Latrina LXXta pedes longitudinis, latitudinis XXti et

tres; sellae XL et quinque in ipsa domo ordinatae sunt, et per

unamquamque sellam aptata est fenestrula in muro altitudinis

pedes duo, latitudinis semissem unum, et super ipsas sellulas

compositas strues lignorum, et super ipsas constructionem

lignorum facte sunt fenestrae Xeë et VIItë, altitudinis tres

pedes, latitudinis pedem et semissem).[680]

The specifications for

this building disclose a perspicacious awareness of the need

for light and ventilation: two tiers of windows, sixty-seven

in all. Since each seat is provided with its own window the

latrines must have been ranged along the outer walls of the

building, as shown in figure 501, which is based on the

dimensions recorded in the Farfa text and the assumption

of a surface area 2½ feet square for each seat.

THE MONKS' LATRINE OF CHRISTCHURCH

MONASTERY AT CANTERBURY

An early graphical portrayal of such a latrine is the Norman

necessarium shown on the famous plan of the waterworks

of the monastery of Christchurch, Canterbury

(fig. 502), drawn around 1165 by Wibert or one of his

assistants.[681]

The foundations and lower portions of the

walls of this privy survive (fig. 503). It was 145 feet long

and 25 feet wide (internal measurements) and in its original

form contained fifty-five toilet seats in a single room, at

intervals of 2 feet, 7 inches, measuring the seats on their

centers. The seats were supported by fifty-three transverse

arches which bridged a fosse flushed by running water.[682]

Two plans of the waterworks of the monastery of Christchurch

are inserted into the Canterbury Psalter on fol. 284v and fol. 285; see

James, 1935, last two plates; for more details on these plans see I, 68-70.

For a detailed description of the rere-dorter of Christchurch

monastery, see Willis, 1868, 85ff.

OTHER MONASTIC PRIVIES

AND WATER-FLUSHED CHANNELS FOR WASTE

The remains of many other structures of this kind, dating

from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, may be found

in other English monasteries, such as Kirkstall, Fountains,

Lewes Priory, Rievaulx, Roche, and Byland; an unusually

fine Continental specimen exists in the Abbey of Maubuisson.[683]

502. CHRISTCHURCH, CANTERBURY, ENGLAND, PLAN OF WATERWORKS (CA. 1165)

MONKS' PRIVY (DETAIL, ACTUAL SIZE)

[By courtesy of the Trustees of Trinity College Library, Cambridge University]

The plan, probably drawn by Wibert (d. 1167), who engineered the system, shows the privy lying at the southern side of the CURIA at right

angles to the Norman dormitory (DORMITORIUM). With an external length of 155 feet (more than double the length of the monks' privy at

Cluny), and a height of 35 feet, it was an imposing structure.

The artist took license in portraying the Christchurch privy as a detached building; remaining fragments of the masonry of dormitory and

privy show that in reality a portion of its western gable wall butted against the dormitory and was accessible from it through a connecting

vestibule (fig. 503.A).

The privy was water-flushed down its length by means of a drainage ditch that, on the drawing, is shown to run parallel to and outside the

structure; in actuality this channel passed beneath it (fig. 503. B, C) and emptied into the fosse of the city wall.

After the dissolution of the monasteries in England by Henry VIII, the privy was converted into a common hall for minor canons and officers

of the choir. So it remained with slight modifications until 1850, when it was taken down. Some of the masonry of the fosse and many of the

arches that supported the privy seats (fig. 503.C) are part of the surviving ruins and can still be seen.

The complete plan of the Christchurch waterworks is reproduced in Volume I of this work, pp. 70-71, and is part of a discussion of schematic

waterways as they might apply to Christchurch; the discussion includes a schematic speculation of watercourses that might be applicable to the

St. Gall site (I, 72, and 74, fig. 53).

503.A CANTERBURY, CHRISTCHURCH MONASTERY, MONKS' PRIVY. PLAN

[after Willis, 1868, fig. 12]

The designations are misleading. The "Third Dormitory" was not a hall for sleeping, but a latrine. The "Second Dormitory" may have served

as sleeping quarters for certain conventual officers, such as sacristan, chamberlain, cellerar, and superior.

cleansed by running water diverted from a natural stream

at some point above the monastery and returned to it with

the waste further down the valley. There is no doubt in

my mind that the majority of the privies shown on the

Plan of St. Gall were cleansed in this manner, although

the author of the Plan refrained from delineating the course

of such a water system. What he had in mind can be

elicited from the fact that the majority of his privies are

sited in such a manner that they could be flushed in

succession by a drainage channel connecting them in a

straight course.[684]

For Kirkstall, see St. John Hope and Bilson, 1907, 73ff; for Fountains,

Wainwright, 1962, 47-48; for Lewes Priory, Godfrey, 1933, 23;

for Rievaulx, Peers, 1934, 8; for Roche, Thomson, 1962, 11; for Byland,

Peers, 1952, 9; for Maubuisson, Lenoir, II, 1856, 367.

VARIATION IN ARRANGEMENT OF SEATS

An interesting, and possibly common, variation of the

longhouse represented by the rere-dorter of the monastery

of Christchurch in Canterbury (figs. 502-503) was created

by moving the row of toilet seats away from the wall into

the center axis of the building and making each alternate

seat accessible from the opposite side. We have the good

fortune of being able to visualize the furnishings of such a

privy down to its minutest detail because of the survival,

in the Collection of Drawings of the British Museum, of a

set of meticulously measured drawings made by J. G.

Buckler in 1868, before the interior of the longhouse of

New College, Oxford, was gutted to make room for more

modern installations.[685]

Although this type does not appear

on the Plan of St. Gall, the furnishings as such may well

reflect a very old tradition. In the annals of New College

the rere-dorter of New College, varyingly referred to as

domicilium necessarium and as "longhouse," was part of the

quadrangle complex built by Bishop Wykeham from 1380

to 1386. It is 16 feet, 2 inches wide and 82 feet long (clear

inner measurements; the external dimensions are 22 feet,

9 inches by 89 feet, 4 inches) and was built two stories

high with walls 3 feet thick. The lower story originally had

no openings and served as a cesspool, which was periodically

cleaned.[686]

The upper story, approached by an external

stair, was lit by narrow slit windows with a wide internal

splay. In the axis of the room throughout its entire length

CANTERBURY, CHRISTCHURCH MONASTERY. MONKS' PRIVY

503.B TRANSVERSE SECTION

[after Willis, 1868, fig. 13]

503.C ARCHES SUPPORTING PRIVY SEATS

[after Willis, 1868, fig. 14]

A longitudinal wall separated the lower part of the privy into two portions of unequal width. The southern part, 14 feet wide, was filled with

earth and paved at the top. The northern part, 7 feet wide, formed a fosse bridged over by thin masonry arches, and carried wooden seats and

seat partitions.

rear and to the side, making the seats accessible from

opposite sides in alternate sequence. Figure 504A-D shows

the plan, sections, and exterior view of this structure and a

detailed view of one of the original seats.

The rere-dorters of the monks and lay brothers of Kirkstall

Abbey, Yorkshire, as well as the Monks' privy of the

Abbey of Maubuisson (Seine-et-Oise), had this same axial

arrangement of seats (and there were unquestionably many

others), but unlike the longhouse of New College, Oxford,

these buildings were flushed by running water.[687]

London, British Museum, Collection of Drawings, Add. Ms.

36437. Buckler, Architectural Drawings, Miscellaneous, vol. VIII, fols.

271-86. The existence of these drawings seems to have escaped the

historiographers of Oxford. They are mentioned neither in the chapter

on New College of the Victoria History of the Counties of England,

Oxfordshire, III, 1954, 144-62, nor in A. H. Smith's New College and

its Buildings (Oxford Univ. Press, 1952).

DISPOSAL OF WASTE BY WATER:

AN URBAN, NOT A RURAL PRACTICE

Disposing of human waste by using water power is an idea

monks inherited from the Romans. It was an urban, not a

rural, invention. In a purely agricultural society the nitrogenous

content of this matter was far too valuable a substance

for replenishing the soil to be discarded in a stream.

The monks whose background was rural could not help

being impressed by the skillful engineering that went into

these water systems and lent to a primordial problem of

nature a touch of inventive elegance. Now and then, in

medieval sources, one runs into a passage that seems to

504.A OXFORD UNIVERSITY, NEW COLLEGE

COLLEGE PRIVY BUILT BY BISHOP WYCKHAM BETWEEN 1380 AND 1386

PLAN OF THE UPPER FLOOR. DRAWINGS BY J. G. BUCKLER [504. A, B, C, D, E]

LONDON, BRITISH MUSEUM COLLECTION OF DRAWINGS, ADD. MS. 36437. BY COURTESY OF THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM

Lobbensium which lists the following among the accomplishments

of Abbot Levinus (twelfth century):

He built a new but more elegant room of sewers, joined to the dormitory,

in the place of the old one (literally: from the old one);

which room, below cleansed from filth by incessantly running

water, he made more honorable above for the necessary use with

seats furnished by suitable beauty.[688]

Gesta Abbatum Lobbensium chap. 23, ed. Arndt in Mon. Germ.

Hist., Scriptores, XXI, 1869, 326-27: "Domum cloacarum dormitorio

coniunctam de veteri novam opere elegantiori aedificavit, ut Quam acqua

indeficienter pretercurrens inferius sordibus mundam rederet forma competens

superius aptatis sedibus honestam usui necessario facerit."

PHILOSOPHICAL IMPLICATIONS

In other sources one finds undertones of a feeling that

the currents of water so skillfully channeled through the

monastic workshops cleansed the monastery in a deeper

sense than the purely physical; the impressive, and in

parts truly poetic, thirteenth-century description of the

waterways of the monastery of Clairvaux, after a minute

account of all the services that the water rendered to the

various offices and workshops, terminates with:

Lastly, in order that it may not omit any thanks due to it, nor leave

the catalogue of its services in any way imperfect, it carries away

all dirt and uncleanness and leaves all things clean behind it. Thus

after having accomplished industriously the purpose for which it

came, it returns with rapid current to the stream and renders to it

in the name of Clairvaux thanks for all the services that it has performed,

and replies to its salutation with worthy response.[689]

One of the puzzling aspects of the Plan of St. Gall is

the fact that although its author is scrupulously precise in

the specifications of the privies that answer the needs of

the monks and their noble visitors, the question of privies

is not even raised on the level of the serfs, the workmen,

504.B OXFORD, NEW COLLEGE. LONGITUDINAL SECTION

A strikingly functional and no less sophisticated solution to the problem of monastic sanitation was applied in medieval university life (where

students, while not cloistered, were in minor orders). The carpentry was superb; seats facing opposite sides in alternating sequence offered a

maximum of privacy and comfort without violating the traditional monastic regulation that even while engaged in the most humble of human

pursuits, none may enjoy the privilege of total seclusion.

provision of space for such) is most strongly felt in the

case of the Great Collective Workshop and the Hospice for

Pilgrims and Paupers.[690] This is not an oversight, in my

opinion, but a case of social discrimination. From a certain

level downward the designer of the scheme left the solution

of the individual privy to the ingenuity of the builder. In

the case of those structures housing both humans and

animals this poses no problem, as the sanitation of the

human occupants is subject to the same order of cleanliness

that governs good animal husbandry and can be met with

the greatest of ease by an infinite variety of ingenious

improvisations. But in the case of the Great Collective

Workshop and the Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers, the

absence of privies—or even of the provision of space for

504.C OXFORD, NEW COLLEGE.

EXTERIOR VIEW FROM NEW COLLEGE LANE

to express himself on this issue.

The Consuetudines Farfenses furnishes us with an interesting

literary parallel for this discriminatory planning procedure.

The same text that tells us with firm precision that

the number of toilet seats in the House for Distinguished

Guests should be equal to the number of visitors who can

be bedded in this structure, wastes not a single word on

the subject of privies of the large building—280 feet long

and 25 feet wide—which contains on the ground floor the

stables for the horses of the royal party and on the upper

floor the eating and sleeping quarters of the lower ranking

members of the emperor's train:

Near the Southgate and [extending from there] to the Northgate,

westward, let a house be built, 280 feet long and 25 feet wide. There

establish the stables for the horses, divided into stalls; and above

let there be a solarium where the servants eat and sleep; here tables

should be installed, 80 feet long and 4 feet wide.[691]

504.E DETAIL

504.D OXFORD, NEW COLLEGE

The roof belongs to the same period that produced

the magnificent carpentry of the 14thcentury

hall of Nurstead Court, Kent (fig.

346.A-D) and is similar to it.

The roof of New College privy is carried by

nine trusses, spaced at intervals slightly less

than 10 feet. Their elegant, sharply cambered

tie beams, chamfered underneath, are dovetailed

into the wall plates. King posts rising from mid

beam carry a center purlin surmounted crosswise

by a collar piece bracing the rafters midway.

Short vertical uprights steady the rafters at

their springing.

Outhouses with seating capacities comparable

to that of the necessarium of New College are

recorded in the most distant parts of medieval

Europe, in both monastic and secular life. A

monks' privy with two rows of seats (19 in all)

backing each other along the center axis of the

structure was built for the monastery of

Batalha, Portugal, shortly after 1388 (for

plans, see Lenoir, 1856, VII 6: 2, 366); in the

northernmost fringes of the world, Old Norse

sagas refer to royal "long houses" that could be

used simultaneously by 22 men (for sources see

Gudmundsson, 1899, 247).

TRANSVERSE SECTION

We close PART V with a charming and amusing verse, its presence in "a certain monastery, perhaps Tours" testifying another equally

humble and traditional use of such structures.

IN LATRINO[692]

Luxuriam ventris, lector, cognosce vorantis,Putrida qui sentis stercora nare tuo.

Ingluviem fugito ventris quapropter in ore:

Tempore sit certo sobria vita tibi.

—translation by Charles W. Jones

Here, friend, may you ponder ingluvial excess,

As your nostrils distend with the stink of the cess.

Now avoid crapulence and eschew overchewing

Lest at Judgment intemperance prove your undoing.

END OF PART V

505. ST. GALL. VIEW OF THE CITY FROM THE WEST, IN 1545

HEINRICH VOGTHERR. WOOD ENGRAVING (29.6 × 42cm)

The rendering shows the town and its surroundings from an imagined perspective in the air. Not yet separated, abbey and town are enclosed by a common masonry wall

elaborated by towers, houses, and two main gates. A glimpse of the Bodensee (Lake Constance) orients the view to the northeast.

Dominating the countryside are meadows cleared for bleaching linen, a local industry. The view is crowded with dwellings, farms and outbuildings, an inn, a fort,

barracks and parade ground, an exercise and training yard. The main access road appears smooth and well paved approaching the city's crenellated gate; down the

other, rougher road a carter gallops three span of horses hitched to a drey, laden perhaps with baled linen. A group of buildings amid trees (center, right) suggesting

modest dwellings is situated outside the city walls. By mid-16th century, St. Gall clearly consisted of URBS and SUBURBS, a dichotomy that attested the arrival

of modern times.

The four largest meodows are bisected by the Irabach; its water-course, now underground, formed a natural boundary between town and monastery in the early Middle

Ages. Two mills locate the cascade of the Steinach; its course deflects sharply westward, broken by the escarpment of the monastery site (cf. fig. 514, p. 331.) The

abbey church lies slightly south of the east-west axis of this rise of land, its staggered roofs indicating various steps of construction. Similar views from different angles

(figs. 507, 509.X) confirm the veracity of the rendering.

Photo: Courtesy of Zentralbibliothek, Zürich, Department of Prints and Drawings.

Each of the two extant prints of this subject is somewhat damaged; this image is

made from a photographic composite of them, in order to obtain the best possible

reconstruction.

Migne, Patr. lat, CLXXXV, 1879, col. 571: "Postremo, ne quid ei

desit ad ullam gratiam, et ne ipsius quaquaversum imperfecta sint opera,

asportans immunditias, omnia post se munda relinquit. Et jam peracto

strenue propter quod venerat, rapida celeritate festinat ad fluvium, ut vice

Clarae-Vallis agens ei gratias pro universis beneficiis suis, salutationi ejus

resalutatione condigna respondeat; statimque refundens ei aquas quas nobis

transfuderat, sic de duobus efficit unum ut nullum appareat unionis vestigium;

et quem dicessu suo teneum et pigrum fecerat mistus ei morantem praecipitat."

For

an equally interesting and even earlier description of the same

water-ways, see I, 69.

Consuedutines Farfenses, ed. Bruno Albers in Cons. mon., I, 1900,

139: "A porta meridiana usque ad portam VIIItem trionalem contra occidentem

sit constructa domus longitudinis CCtu LXXXta pedes, latitudinis

XXti et V, et ibi constituantur stabule equorum per mansiunculas partitas,

et desuper sit solarium, ubi famuli aedant atque dormiant, et mensas habeant

ibi ordinatas longitudinis LXXXta pedes, latitudinis vero IIIIor."

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||