The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V.1.1.. |

| V.1.2. |

| V.1.3. |

| V.1.4. |

| V. 2. |

| V.2.1. |

| 10. |

| 10. |

| V.2.2. |

| V. 3. |

| V.3.1. |

| V.3.2. |

| V.3.3. |

| V. 4. |

| V.4.1. |

| V.4.2. |

| V.4.3. |

| V. 5. |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

THE PFETTENDACH |

| V. 6. |

| V.6.1. |

| V.6.2. |

| V.6.3. |

| V.6.4. |

| V. 7. |

| V.7.1. |

| V.7.2. |

| V.7.3. |

| V.7.4. |

| V.7.5. |

| V.7.6. |

| V. 8. |

| V.8.1. |

| V.8.2. |

| V.8.3. |

| V.8.4. |

| V.8.5. |

| V.8.6. |

| V.8.7. |

| V.8.8. |

| V. 9. |

| V.9.1. |

| V.9.2. |

| V.9.3. |

| V. 10. |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. |

| V. 11. |

| V.11.1. |

| V.11.2. |

| V.11.3. |

| V. 12. |

| V.12.1. |

| V.12.2. |

| V.12.3. |

| V. 13. |

| V.13.1. |

| V.13.2. |

| V. 14. |

| V.14.1. |

| V.14.2. |

| V. 15. |

| V.15.1. |

| V.15.2. |

| V.15.3. |

| V.15.4. |

| V. 16. |

| V.16.1. |

| V.16.2. |

| V.16.3. |

| V.16.4. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| V.18.1. |

| V.18.2. |

| V.18.3. |

| V.18.4. |

| V.18.5. |

| VI. |

| VI. 1. |

| VI.I.I. |

| VI.1.2. |

| VI.1.3. |

| VI.1.4. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI.2.1. |

| VI.2.2. |

| VI.2.3. |

| VI.2.4. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI.3.1. |

| VI.3.2. |

| VI.3.3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI.4.1. |

| VI.4.2. |

| VI.4.3. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

THE PFETTENDACH

The Sparrendach works with only one kind of rafter; the

Pfettendach differs from it in employing two kinds—one

of light, the other of heavy, scantling. The heavy, or

principal, rafters rise from the ends of the tie beams to the

ridge of the roof, forming powerful trusses that carry

purlins and, as a rule, a ridge piece; and it is upon these

longitudinal timbers (purlins and ridge piece) that the

lighter common rafters of the roof are mounted. In the

Pfettendach the major burden of the roof is transmitted

by the purlins to the principal trusses which discharge it

upon the walls at the beginning and at the end of each bay,

to points which, if the walls are built in masonry, are usually

reinforced by buttresses.

The best known variant of the Pfettendach is the roof of

the Early Christian basilica[208]

and all its Mediterranean

medieval derivatives. But the Pfettendach is also, as we

have seen, the standard roof in the North Germanic

territories of Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Iceland.[209]

The two earliest surviving examples of a vernacular

medieval Pfettendach are the roofs of the barn of the abbey

grange of Great Coxwell in Berkshire, a dependency of the

Cistercian Abbey of Beaulieu in Hampshire (figs. 349-354)

and the barn of the abbey grange of Parçay-Meslay, near

Tours, in France, a dependency of the monastery of Marmoutier

(figs. 352-355). The former dates from the first

decade of the fourteenth century;[210]

the latter belongs to a

group of buildings that tradition ascribes to Abbot Hugue

de Rochecorbon (1211-27).[211]

The barn of Great Coxwell (figs. 349-351) is 152 feet

long and 44 feet wide (external measurements not counting

buttresses) and reaches a height of 48 feet at the ridge. Its

vast roof rests on purlins which are held in place by

seven principal trusses sustained by posts, and six intermediate

trusses in cruck construction rising directly from

the aisle walls. The uprights of the principal trusses rest on

tall bases of stone almost seven feet high, and are framed

together 30 feet above the floor of the barn, first crosswise

by means of tie beams, then lengthwise by means of

arcade plates—a reversal of the normal and more common

procedure of housing the plates beneath the tie beams in

a recess cut into the head of the supporting posts (fig. 357).

The tall, narrow proportions of these trusses are exciting.

354.A PARÇAY-MESLAY, NEAR TOURS (INDRE-ET-LOIRE), FRANCE

BARN OF ABBEY GRANGE, 1211-1227. PLAN

The twelve roof-supporting trusses of the barn are not in alignment with the buttresses of the two long walls. This could be interpreted to mean

that the present frame of timber is not the original one, if this conclusion were not invalidated by the even more startling observation that the

buttresses of the two long walls fail to align with one another. An oral tradition, the precise sources of which we have not been able to identify,

claims that the original roof of the barn was destroyed by a fire in 1437 during the war with the English. Radiocarbon measurements taken of

samples extracted from two different posts did not confirm this tradition (see Horn, 1970, 28; and Berger, 1970, 111-112).

It is possible that the craftsman who built the masonry shell of the structure did not know what the carpenter had in mind; and even the

carpenter, in many cases might not have known of what number of trusses his roof-supporting frame of timber would be composed until he was

apprised of the length and strength of the available timbers. In its ultimate form the roof was composed of twelve trusses dividing the space

internally into thirteen bays each of a depth of 13 feet. The location of the buttresses would have suggested a barn of seven bays, each of a depth

of 24 feet, which is possible but structurally more risky.

354.B PARÇAY-MESLAY, NEAR TOURS (INDRE-ET-LOIRE), FRANCE

BARN OF ABBEY GRANGE, 1211-1227. TRANSVERSE SECTION

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the only surviving five-aisled medieval barn of transalpine Europe. There were others. The plan of the

abbey of Clairvaux and its grange of Ultra Alba (a short distance away on the opposite bank of the river Aube) records, besides two five-aisled

structures of this type, two barns that even had seven aisles. The largest among these was 210 feet long and 120 feet wide; 40 feet longer and

wider than Parçay-Meslay (for a plan and bird's-eye view see Horn and Born, 1968, Pl. XIX, figs. 10 and 11).

Since most Cistercian monasteries possessed between ten and fifteen outlying granges, the number of buildings of this kind must have been legion.

Clairvaux and Morimond counted twelve; the Abbey of Foigny fourteen; the Abbey of Fontmorigny seven; and the Abbey of Chaalis, fifteen.

On many granges, as in Ultra Alba, there were not one but two or even more such structures. Since at the beginning of the 13th century there

existed in France some 500 Cistercian monasteries, the total number of barns of this order only, and in France only, must have ranged

between 5,000 and 10,000.

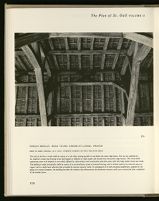

355. PARÇAY-MESLAY, NEAR TOURS (INDRE-ET-LOIRE), FRANCE

BARN OF ABBEY GRANGE, 1211-1227. INTERIOR LOOKING UP INTO THE ROOF RIDGE

The roof of the barn is made stable by means of a sub ridge running parallel to and below the main ridge beam. The two are stiffened by

St. Andrew's crosses (two bracing struts half-lapped at midpoint at right angles and tenoned into the paired ridge beams). This remarkable

engineering came to be adopted in and widely diffused by 19th-century steel construction some 600 years after this huge timber frame was made.

The building is made structurally stable by means of its extraordinary system of internal bracing, and is without need of an external source of

support such as might have otherwise been provided by massive masonry walls. In consequence of its self-contained equilibrium, supplied by the

genius of a master carpenter, the building provides the evidence that demonstrates the handsome masonry walls were constructed after completion

of the wooden frame.

which rise from the main posts to their connecting long

and cross beams. By reducing the unsupported length of

the beams that they brace to less than one third of their

total length, they prevent them from sagging under the

weight of the superincumbent rafters, while at the same

time protecting the frame from rocking and swerving. The

walls are built in roughly coursed rubble with buttresses of

high quality ashlar masonry. The two large doors in the

gable walls are modern. In the Middle Ages the barn was

entered broadside through two transeptal porches, one of

which had on its upper level the office of the supervising

monastic granger.

The barn of Parçay-Meslay (figs. 352-355) is quite

as impressive. It lacks the breathtaking steepness of

Great Coxwell, but its space is of a vastness that can only

be compared to that of an Early Christian basilica or of a

modern airplane hangar. It has a clear inner length of 170

feet, and a clear inner width of 80 feet. From floor to

ridge it measures 44 feet. Its vast tile-covered roof is

supported by twelve aisled trusses which divide the space

lengthwise into a nave and four aisles. The barn of ParçayMeslay

is the only example of this type to have survived

the French Revolution; but the existence of other barns

of similar design and even larger dimensions, dating from

the twelfth century, is attested by Dom Milley's engravings

of the Abbey of Clairvaux, published in 1708.[212]

It is a

purlin roof like Great Coxwell, and similar in many other

respects, but the trusses of Parçay-Meslay are more closely

spaced and are all of the same design. The assemblage of

arcade plate and post follows the more common pattern of

housing the plates in the head of the posts and locking the

tie beams into both of these members simultaneously from

above by means of dovetail joints and mortice-and-tenon

joints. The bracing struts are short and sturdy, and the

posts throughout have joweled heads.

As in Great Coxwell the purlins ride on the back of

principal rafters that run parallel to the common rafters,

a short distance farther inward (figs. 353-354). As in Great

Coxwell these inner rafters are braced by diagonal struts

that rise from the top of the tie beam. In Great Coxwell

the principal rafters over the nave terminated in the ends of

a collar beam that stiffened the corresponding pair of outer

rafters some distance below the ridge of the roof (fig. 350).

In Parçay-Meslay they are buttressed against a king post

that reaches all the way up to the ridge of the roof (fig. 354).

There are other differences. Unlike Great Coxwell, Parçay-Meslay

has no gable trusses. Instead, all longitudinal

members (plates and purlins) terminate in sockets built

into the masonry walls. A more important difference, however,

is that while in Great Coxwell a major portion of the

roof load is transmitted to the masonry of the long walls,

in Parçay-Meslay it is almost entirely absorbed in the

timber frame. The walls, of course, contribute their share

in steadying the work, but there is a complete set of outer

posts addorsed to the walls on either side of the barn, making

the timber frame virtually autonomous. In Great Coxwell

the buttresses of the masonry walls are in careful alignment

with the timber frame. In Parçay-Meslay carpenter and

mason went separate ways. No single buttress is in line

with any of the timber trusses.

One of the most remarkable features of the carpentry of

Parçay-Meslay is the measure taken, both in the lower and

upper stage of the trusses, to restrain the frame from moving

longitudinally. In the lower stage this is accomplished by

straining beams running parallel to the arcade plates, some

12 feet beneath them. They are tenoned into the posts just

below the springing of the main braces and are braced in

turn by short angle struts (fig. 353). In the upper stage of

the trusses the same task is performed by the introduction

of a sub-ridge running parallel to the main ridge, some 9

feet beneath it, and stiffened in its relation to the main

ridge by means of St. Andrew crosses (fig. 355)—a notable

piece of engineering.

The roof of Parçay-Meslay is a typical Continental purlin

roof, of a kind that is well attested through many other

Continental barns of the thirteenth century.[213]

This type

was still in use in the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth

centuries as the standard form for the roof of market halls.[214]

The grange lies 9 km. northeast of Tours and ca. 1 km. north of the village of ParçayMeslay.

Marmoutier, its mother house, lay on the outshirts of Tours and slightly

upstream, on the Loire's north bank; nationalized in 1818, the abbey was then razed.

The grange at Parçay-Meslay stands as a solitary reminder of the former grandeur of

this abbey, once among the most powerful houses of Christendom.

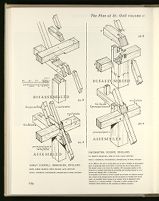

GREAT COXWELL, BERKSHIRE, ENGLAND

357.B

357.A

BARN, ABBEY GRANGE, FIRST DECADE 14TH CENTURY

DETAIL: ASSEMBLED, DISASSEMBLED, principal post, tie beam, roof plate

CHICHESTER, SUSSEX, ENGLAND

356.B

356.A

ST. MARY'S HOSPITAL, END OF THE 13TH CENTURY

DETAIL: ASSEMBLED, DISASSEMBLED, principal post, tie beam, roof plate

At St. Mary's, the roof or arcade plates are set into a shoulder of the principal

posts. A projecting tenon of the latter is mortised into the tie beam which in

this manner comes to rest above the roofplate. All converging members of the

frame are so carefully interlocked by protruding and receding elements so as to

prevent any slipping, shift, or dislocation.

In the joinery of the Barn of Great Coxwell the tie beams are likewise mortised

into a tenon of the principal posts, but the roof plates are notched over the tie

beam—an assembly which, because of its relative rarity in England is there

referred to as "reversed assembly". The latter is rather common on the

Continent. Both methods are fine examples of medieval carpentry.

Cf. above, pp. 45ff. and M. Wood, "13th-century Domestic Architecture

in England;" 1950, 1-150.

For this date see Siebenlist-Kerner, Schove, and Fletcher, "The

Barn at Great Coxwell," in Dendrochronology in Europe (forthcoming)

that supplants radiocarbon dating by Horn and Born, 1965; Horn and

Berger, 1970.

The general character of the masonry work of the barn is in full

accord with this date. There is some question, however, of whether the

present timbers of the barn of Parçay-Meslay are the original ones.

Aymar Verdier, who discussed this building in his Architecture civile et

domestique (Verdier, 1864, 37-35), reports that M. Drouet, who acquired

the barn after the French Revolution and saved it from demolition, was

of the opinion that the original frame of timber had caught fire during

the invasion of the Touraine by the English in 1437. I have no means of

judging whether this view is based on any valid historical evidence. But

even if the present timbers were proved to date from the fifteenth

century, this would have little bearing on our argument since a sufficient

number of other thirteenth-century barns survive to indicate that the

type of carpentry employed in Parçay-Meslay was widely used in the

thirteenth century; cf. Horn, 1958, 12-14.

For a good sampling of these buildings (with which Ernest Born

and I shall deal extensively in a separate study) see Horn, 1958, 13ff.

Other French thirteenth-century barns with purlin roofs are: Ardennes

(Calvados), Beauvais St.-Lazare (Oise), Canteloup (Eure), Cire-les-Mello

(Oise), Fay-les Etangs (Oise), Maubuisson (Seine-et-Oise),

Perrières (Calvados), Troussure (Oise), Vaumoise (Oise), Vaulerand

(Seine-et-Oise).

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||