THE BREWERY

From Babylon and Egypt to St. Columban

Beer is a malted beverage that was brewed in Babylon and

Egypt from primordial times[572]

but it was held in low esteem

by the wine-loving Greeks and Romans, and because of

this deeply rooted cultural aversion made no imprint whatsoever

on early monastic life, from the literature of which

the terms cerevisa or celia are wholly absent. The drink

acquired significance, however, as monachism spread into

the north and west of Europe where beer has been a

traditional beverage since the remotest times and where wine

was as yet not made in sufficient quantities to take care of

all of the needs of the monks.

Pliny describes caelia, cerea and cerevisia as words of

Celtic origin denoting beverages drunk in his days in

Spain and in Gaul and remarks that its froth was used by

the women of these countries as a cosmetic for the face.[573]

The terms do not occur at any place in the Rule of St.

Benedict. The earliest evidence of the consumption of beer

in a monastic context, to the best of my knowledge, is a

passage in the Life of St. Columban, (543-615) written by

the monk Jonas of Bobbio (ca. 665) which relates that in the

days of Columban, beer was served in the refectory of the

monastery of Luxeuil (founded by St. Columban ca. 590).

In this account cervisia is referred to as a beverage "which

is boiled down from the juice of corn or barley, and which

is used in preference to other beverages by all the nations

in the world—except the Scottish and barbarian nations who

inhabit the ocean—that is in Gaul, Britain, Ireland, Germany

and the other nations, who do not deviate from the

custom of the above."[574]

Basic procedures in the making of beer

Beer is brewed in a number of different ways, resulting

in a variety of different brews. The manufacture of all of

them has certain basic steps in common:

1. First, grain, usually barley, is "malted," i.e., allowed

to steep in water until it begins to germinate, and starches

in the grain undergo chemical changes that produce

sugars.

2. Then the malted grain is mashed and infused in

gradually heated water, the temperatures of which are

raised in stages to 165° or 175°F. This heating arrests the

germination of the malted grain and results in a liquid

known as wort (sweet wort) which retains the natural

sugars and enzymes generated by infusion.

3. After completion of the infusion process the wort is

transferred to a kettle and to it is added the blossoms of

hops that give beer its characteristic aroma and flavor. This

mixture of wort and hops (hopped wort) is boiled for about

two hours.

4. After this operation is completed the liquid is

cleansed by straining out the hops and sediments, and

filtered into a cask or trough for cooling. At this point

the yeast is added to the wort and fermentation begins.

Beer may be fermented in a variety of ways, but until

relatively recently, the process favored on the Continent

was that of top fermentation, in which the yeast rises to

the top of the fermentation vat and is there skimmed off

when fermentation is complete. Some beers can be drunk

immediately after fermentation is complete. Others, particularly

those made by top fermentation are stored in

casks from two or three weeks to six months. During the

storage period the beer brightens and becomes charged

with carbon dioxide. Beer fermented in this way is stored

in an ambient of 58°-70°F, a condition entirely consonant

with temperatures that could be maintained both in the

Monks' Brew House where fermentation of the beer was

instigated, and in the great cellar used for wine and beer

storage (see I, 292-307).

Layout and equipment

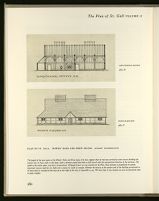

On the Plan of St. Gall, the monks' brewery lies in the

western half of the Monks' Bake and Brew House (fig.

462). It covers the same area as the bakery, but has no

lean-to on the narrow end of the building. The space in

which it is accommodated is marked by the title "Here let

the beer for the brothers be brewed" (hic fr̄ībus conficiat

ceruisa). It is reached from the monks' bakery and has no

separate access from the outside. The monks' brewery is

furnished with all the equipment needed in brewing: a

stove with four ranges for heating water and boiling wort

with hops. The stove is identical in design with the large

stove in the Monks' Kitchen.[575]

Around that stove four

round objects are shown—vats or cauldrons, no doubt,

wherein the grain was steeped for malting, and infusion

was done. These could have consisted either of simple

wooden tubs, or of heatable cauldrons or of a combination

of both, and may have been in shape or construction like

any of those shown in figure 387 and 390. The south

aisle of the brew house serves as a cooler. It is furnished

with two troughs and a vat, explained by the inscription

"Here let beer be cooled" (hic col&ur celia). Here the

yeast was added to the worted liquid and fermentation

began. From the cooling troughs unquestionably the beer

was moved to casks in the cellar, and allowed to finish

fermenting and clearing, before it was brought to the table.

Replacement of wine by beer in ratio of 1:2

We have already drawn attention to the fact that wine was

the traditional monastic beverage, beer only a substitute,

and that a ruling of the Synod of 816 directed that if

shortages in wine had to be made up for by beer, this should

be done in the ratio of 1:2.[576]

Therefore, if such an emergency

arose, beer would have had to be available in considerable

quantities. Abbot Adalhard of Corbie allows each

visiting pauper a ration of 1.4 liters of beer per day.[577]

If

this same amount were issued to the monks and the serfs

of the monastery, this would mean that the monastery

shown on the Plan of St. Gall issued 350 to 400 liters a

day. Over a period of time, this practice would have required

storing a considerable volume of beer. Unlike wine,

beer is not a seasonal product, but can be manufactured

continuously, and in the monastery it probably was manufactured

continuously, like the bread in the nearby bakery.

Today the brewing of beer is almost exclusively in the

hands of commercial firms. Throughout the major part of

the Middle Ages it was a small-scale domestic operation.

Before the twelfth and thirteenth centuries when brewing

first emerged as a commercial venture, the monastery was

probably the only institution where beer was manufactured

on anything like a commercial scale.

Use of hops as a flavoring agent

The explanatory titles of the various bake and brew

houses of the Plan of St. Gall contain no direct reference to

the use of hops as a flavoring agent in the production of

beer, but it is quite possible that a tacit allusion to this

plant is hidden in the second half of the title which defines

the Brewers' Granary as the place "where the cleansed

grain is kept and where what goes to make beer is prepared"

(granarium ubi mandatū frumentum seru&ur & qd ad

ceruisā praeparatur).[578]

This granary is ideally located, in

the middle between the Monk's Brewhouse and their

Drying Kiln—which in addition to serving as a facility for

parching fruit and grapes, could also have performed the

function of a monastic oast house.[579]

There is sufficient evidence to make it clear that the

hopping of beer was in the early Middle Ages a widespread

monastic practice north of the Alps. In his Administrative

Directives of A.D. 822 Abbot Adalhard of Corbie addresses

himself in detail to the procedures that should control the

tithing of hops and their distribution among the various

monastic officials placed in charge of brewing.[580]

He makes

it a point to exempt the miller from making malt or from

growing hops (nec braces faciendo nec humulonem) because

of the weight of his other duties.[581]

Ural-Altaic origins

The origins of the use of hops as a constituent ingredient

in brewing is an intriguing literary and linguistic subject.

E. L. Davis, and others before him, have drawn attention

to the importance given to hops in the folklore of Finland

and the Caucasus region and believed to reflect a cultural

heritage of great antiquity. They thus inferred that hops

were used as an ingredient for beer in the northeast and

east of Europe long before this practice was introduced in

western Europe.[582]

In a more recent study, Arnald Steiger

traced the origin of the custom even further eastward.

The earliest word forms for hops (best reflected in Old

Turkish qumlaq), Steiger contends are found in a variety of

Ural-Altaic languages of great antiquity. From there the

term migrated west into the orbit of the Slavic languages

(Old Slavic chǔmelǐ and through the latter into the North

Germanic language groups (Old West Nordic humili) which

transmitted it to the Salian and Ripuarian Franks (Middle

Latin humelo . . . leading to Modern French houblon). This

evidence, Steiger argues, suggests that the practice of

hopping beer originated in Central Asia and was transmitted

from there to Northern and Western Europe by the

Slavs along the linguistic channels indicated by the

migration of the word for hops.[583]

The Greeks knew the plant only in its uncultivated state

(and under a different name), but the Romans grew it in

their vegetable gardens and used it as a flavoring agent for

salads.[584]

Earliest medieval mention of hops

Probably the earliest medieval mention of the plant is a

charter of A.D. 768 in which King Pepin the Short deeded

some hop gardens (homularia) to the monastery of St.Denis.[585]

During the reign of Charlemagne and Louis the

Pious the evidence multiplies. Abbot Ansegis (823-833)

lists amongst the annual deliveries to be made to the Abbey

of St.-Wandrille (Fontanella): "beer made from hops, as

much as is needed" (sicera homulone quantum necessitas

exposcit).[586]

Hops were part of the revenues paid to the

Abbey of St.-Germain-des-Prés from several outlying

possessions (The fiscs of Combs-la-Ville, of Marenil and of

Boissy),[587]

and the plant is mentioned in various places in

deeds of the abbey of Freisingen, dating from the reign of

Louis and Pious as well as from later periods.[588]

All of these references to the plant, in conjunction with

the detailed directives issued by Abbot Adalhard on the

tithing and internal distribution of hops leave no doubt

that, at the time of Louis the Pious, hops had become a

customary ingredient of beer produced in the transalpine

monasteries of the Empire.[589]

One of the beneficial effects of its admixture, besides the

distinctive flavor it imparted to the brew, was that owing

to its antibiotic properties it prolonged the life of beer

considerably over that of the older and more perishable

ale.[590]

This was of great importance when storage in bulk

was required and where transportation was involved—as

they inevitably were in the beer economy of a monastic

settlement.

Contemporary sources make it quite clear that not

all the beer consumed by the monks and their serfs

was brewed inside the monastic enclosure. All the larger

outlying agricultural holdings, and many of the smaller

ones, had their own facilities for brewing. The delivery of

a tenth of their home-brewed beer was a standard procedure

in the tithing of tenants. Records of these tithes

appear in the deeds of the monastery of St. Gall from as

early as the middle of the eighth century. Some of the

tenants had licenses to set up taverns, and many of these

continued to pay for their tenancy through the delivery of

beer even later, when all other forms of tithing in naturalia

had been abolished.[591]

Work in the bake and brew house:

a privilege of the monks

Working in the Bake and Brew House was one of the

manual labors traditionally required of the brothers, and

so specifically stipulated both in the preliminary and the

final resolutions of the First Synod of Aachen (816).[592]

The

brothers apparently liked this work, since one of the protests

lodged before the emperor in the same year by the

monks of Fulda about the hardships brought upon them

by Abbot Ratger's excessive building program included the

complaint that it deprived them of their traditional right

to work in the Bake and Brew House (pistrinum and brati-

arium).[593]

It does not seem far-fetched to suppose that the

constant warmth of the bakery attracted the brothers to

the chore of breadmaking. During the long northern winters,

when all warmth was leached from the cloister, the

bakery was one of the few places in the community a monk

could work in comfort of body as well as of soul, and

surrounded by the incomparable fragrance of new bread.