V.9.2

THE OUTER SCHOOL

LAYOUT & MEANING OF EXPLANATORY TITLES

The Outer School of the Plan (fig. 407) is surrounded by a

fence which is designated with the hexameter:

Haec quoq. septa premunt, discentis uota iuuentae

These fences enclose the endeavor of the

learning youth

Measuring 70 feet in length and 55 feet in width, its surface

area exceeds that of the House for the Distinguished Guests

by a slight margin. The building consists of a large rectangular

hall, inscribed with the title domus communis

scolae id÷ uacationis. The interpretation of this title is

controversial. Keller, Willis, Campion, Leclercq, and Reinhardt

transcribed the abbreviation id÷ wrongly as idem

and interpreted the term uacatio as "recreation," thus translating

the line as "the common-room of the school and

place for recreation."[358]

Meier transcribed id÷ correctly as

id est[359]

and proposed uacatio is simply a Latinization of the

Greek word σχολή, which came into use in the Latin world

in republican times as the designation for higher studies in

literature, grammar and rhetoric.[360]

He interprets the title

accordingly as "the common hall for the school, i.e. the

place of study." The term uacatio is not used in the Rule

of St. Benedict, but to judge by the frequency with which

it appears in Hildemar's commentary to the Rule (written

around 845) it must have been fashionable in the Carolingian

period. Hildemar employs it no fewer than fifteen

times in a single chapter

[361]

and in one of these places pauses

to furnish his readers with a regular dictionary definition:

"

vacare means to relinquish one thing and to replace it

with some other preoccupation; it is in this sense that he

[St. Benedict] insists, in this chapter that, manual work

being set aside, the time thus released be used for study"

(`

Vacare'

est enim aliam rem relinquere et aliis insistere rebus,

sicuti in hoc loco relicta exercitatione manuum jubet insistere

lectioni).

[362]

In accordance with this definition I would translate

the title

domus communis scolae, id ÷ uacationis as "the

common hall for learning, i.e., for the time relinquished

from other obligations for the purpose of study."

[363]

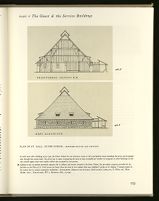

The hall measures 30 feet by 40 feet and is divided in

half crosswise by a median wall. This partition does not run

clear across the room but has wide passages at either end,

suggesting that it was a low freestanding screen rather than

a massive wall and that the large hall, although each of the

two partitions is provided with its own fireplace and louver

(testu), was conceived of as a single space rather than as two

separate rooms. The fact that the inscription that defines

the purpose of this space runs across the wall partition corroborates

this interpretation.

Ranged peripherally around this center space are twelve

"small dwelling rooms for the students" (mansiunculae

scolasticorum hic),[364]

and in the area between them in the

middle of the southern long wall a slightly smaller space

which served as "entrance" (introitus). On the opposite

side a room of like dimensions served as "exit to the outhouse"

(necessarius exitus).

The rooms of the students each measure 12½ feet by 15

feet. They have in the center a small square, which Keller

and Willis interpreted as a table.[365]

I am rather inclined to

think that these squares are the designation for dormer

windows in the lower slope of the roof, of the type shown

in the February representation of the Grimani Breviary

(fig. 367). The two louvers over the center space of the

house, although providing adequate lighting for the two

classrooms directly beneath them, would not have furnished

sufficient light for the pursuit of individual studies in the

student cubicles located in the aisles and lean-to's. Additional

light could, of course, also have been provided by

windows in the outer walls of the house, and with special

ease, if the latter were built in masonry. In our reconstruction

(figs. 408A-E) we have demonstrated both these

possibilities, introducing a volume of light that is probably

in excess of what one would reasonably expect to have been

available in the ninth century. Under no circumstances

should the squares in the students' rooms be interpreted

as fireplaces. Open fires in each of these twelve cubicles

would have constituted a fire hazard of the first degree and

would have been without parallel in any known or excavated

example of this construction type. Moreover, although

many of the students who occupied these rooms may well

have been of noble birth, their status as students was

scarcely of sufficient weight to entitle them to a privilege

otherwise accorded only to the highest ranking dignitaries

of the monastic community.[366]

All of the students' rooms are accessible from the main

hall. The doors are so arranged as to serve as entrance not

for one, but for two cubicles. The existence of these doors

and their carefully planned location leaves no doubt that

the students' rooms were separated from the main hall by

partitions. These partitions, however, could not have run

up to the roof of the house, as the cubicles depended for

their warmth on the open fires that burned in the main hall,

and this, in turn, presupposes a free exchange of air between

the main hall and the students' rooms.

NUMBER OF STUDENTS

The Plan gives no clues as to the number of students to

be housed in these rooms. Each mansiuncula might have

been reserved for a single student. But it could easily have

accommodated two; with less comfort, three. The total

number of students, accordingly, would either have been

twelve, twenty-four, or thirty-six. Since the privy of the

Outer School has fifteen toilet seats, the normal number of

students is likely to have exceeded the minimum number

of twelve.

We have already discussed at sufficient length the fact

that the Plan does not tell us where the students ate their

meals and where their food was cooked.