V. 4

CRITERIA OF RECONSTRUCTION

I

V.4.1

GENERAL SPATIAL COMPOSITION,

Having identified the historical building tradition to which

the guest and service buildings of the Plan of St. Gall

belong, we can now designate as a central hall the large

rectangular center space, which is common to all of its

variants and which is open to the roof and furnished with a

fireplace supplying the house with its warmth. The subsidiary

outer spaces, on the other hand, must be interpreted

as aisles or lean-to's added peripherally to one, two, three,

or all four sides of the hall. This suggests a variety of

elevations, the basic possibilities of which are illustrated in

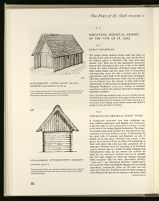

figures 329-334.

In its simplest form the house is covered by a pitched

roof with gable walls on the narrow sides. Typical examples

of this basic form are the bath and kitchen houses of the

Novitiate and the Infirmary (fig. 329), consisting really of

two such spaces added one to the other. In the next stage,

an aisle is added to one side, necessitating a roof extension

over the aisle addition, as in the Annex to the Great Collective

Workshop (fig. 330). In the third stage, a second aisle

is added to the opposite side, requiring a roof extension

over this second aisle, as in the House of the Fowlkeeper

(fig. 331). In the fourth stage, the main space is surrounded

on three sides by peripheral spaces. This permits two

variants: in one of these one of the narrow sides of the

center space remains exposed and contains the entrance, as

in the House of the Physicians (fig. 332); in the other, this

function is performed by one of the long sides, as in the

Gardener's House (fig. 333). The roof over the lean-to, on

the narrow side of these houses, could either be a simple

extension of the aisle roofs with the upper portion of the

gable walls exposed, or it could be slanted up to the ridge

of the roof in the form of a hip, a constructionally superior

form (and in the case of larger houses almost a necessity)

because the rafters of the lean-to act as buttresses protecting

the main roof against longitudinal displacement. We have

demonstrated the first possibility in some of the smaller

houses, such as the House of the Physicians (fig. 332) and

the Gardener's House (fig. 333), but have adopted the

latter version for all of the larger houses of the Plan.

The range of the variants is complete with the addition

of another aisle or lean-to on the fourth side of the center

space (fig. 334). Thus the house attained the distinctive

silhouette so well known from drawings and engravings

of rural landscapes by Albrecht Dürer (fig. 335) and Peter

Bruegel the Elder (fig. 336).

V.4.2

SUPPORTING FRAME OF TIMBER

AND WALLS

The crucial constructional trait of the building tradition

to which the guest and service structures of the Plan of

St. Gall belong is that in this family of houses the roof

received its main support from two rows of freestanding

wooden posts, which divided the building lengthwise into

a nave and two accompanying aisles. The rafters of the

roof had their footing in a course of horizontal logs (plates)

which were held in place by a peripheral row of outer posts,

shorter and not as sturdy as the principal posts. The walls

had, in general, no load-bearing function, and were often

entirely independent from the outer posts. The predominant

material was wattlework, daubed with clay or animal

manure, but there is also clear evidence for vertical and

horizontal weatherboarding. We show as a typical example

of the former a reconstruction of House III of the ninth-century

fortified settlement of Husterknupp in the lower

reaches of the river Rhine (fig. 337),[183]

and as an example of

the second, a reconstruction of a house of the Stellerburg

in Dithmarschen, Germany (fig. 338)[184]

—both dating from

the ninth century. Walls built of earth or turves, as they were

sporadically encountered by van Giffen both in Iron Age

houses and in the early Middle Ages,[185]

are possible, yet not

very likely, in the sophisticated context of a paradigmatic

Carolingian monastery. Log construction is rare, practically

nonexistent, in the time and the territories with which we

are concerned.

[186]

If in our reconstruction of the guest and

service buildings of the Plan of St. Gall we have decided

on daubed wattlework in preference to other solutions, we

have done so not only because the excavations show it to

be the most common method of building walls in early

medieval and protohistoric times—(it might be recalled in

this context that the German word for wall,

Wand, comes

from

winden, "to wind" or "to braid")—but also because

it is still today in vast areas of central and western Europe

the preferred method of constructing infillings for the walls

of timber framed houses.

Since in the majority of the St. Gall houses the central

hearth is the only available source of heat for the entire

building, the peripheral spaces cannot have been completely

screened off from the central hall of the house. Like the

Bajuvarian standard house (fig. 289),[187]

the St. Gall house

was still essentially a unitary structure. In some houses,

however, where there are special corner fireplaces installed

in peripheral rooms the separation could have been more

rigid.[188]

While the literary and archaeological parallels adduced

in the preceding chapter leave no doubt that the traditional

material used in the family of houses to which the guest and

service structures of the Plan of St. Gall belong was timber,

masonry construction cannot be entirely excluded. The

foundations from which the timbers rose, and in certain

cases even the walls or certain component parts of the walls,

may have been built in stone. This would have been

especially desirable for the sake of fire protection in houses

which, in addition to the central hearth, had corner fireplaces

in some of their peripheral rooms. The House for

Distinguished Guests and the House for Bloodletting with

four corner fireplaces each are first in line for such consideration

(see below, figs. 397 and 416). Other houses may

have been built in a mixed technique, such as the House of

the Physicians (fig. 410), where the safety of the rooms with

corner fireplaces may have called for masonry walls, while

the gable wall on the entrance side of the house could have

been timber-framed. We have reconstructed the House of

the Physicians in this manner in order to demonstrate this

possibility (figs. 413A-F). By no means, however, should

masonry walls be taken as a precondition for the presence

of corner fireplaces. Central and Northern Europe, as well

as England, are dotted even today with houses built entirely

of timber and yet equipped with wall and corner fireplaces

built in masonry. A striking historical example of this

combination is found in the February page of the Très

Riches Heures of the Duc de Berry (fig. 378). We demonstrate

this possibility in our reconstruction of the Gardener's

House (fig. 427). For the remainder, and this holds

true especially for all the houses that shelter animals and

their keepers, there is no need to consider anything else but

timber. The

Brevium exempla have taught us

[189]

that even

on the highest social level in the emperor's residencies on

his various estates, stone was the exceptional, timber the

commonly used, material.

V.4.3

UNCERTAINTIES ABOUT THE ROOF

Up to this point, we are on relatively safe ground. The

problem becomes more delicate as we turn from the supporting

members of the roof to the design of the roof itself.

Admittedly all the material evidence that has been brought

to light so far remains confined to those portions of the

building which stuck in the ground or reached vertically

from the floor level of the excavated house to an optimal

height of about 5 to 6 feet—as much as was buried in the

mound of earth and manure that was heaped upon the floor

of an abandoned house when a settlement had to be reconstructed

on higher ground because of the rising water

level. The roofs that lay above this survival level have

vanished entirely and so far no one has been lucky enough

to find a portion sufficiently large and sufficiently well

preserved to obtain some real assurance of the detail of its

constructional make-up. It is quite obvious that the two

rows of freestanding inner posts must have been connected

lengthwise and crosswise by means of plates and tie beams.

Without such connections the supporting frame could not

have withstood the load and thrust of the roof, and especially

not in those cases where the post stood not in the ground

but on stones or masonry bases[190]

—but whether the crossbeams

lay beneath the longitudinal timbers or above them

must remain conjecture. Wholly inexplicable, on the basis

of the archaeological material available at this date, is the

design of the roof itself.

Fortunately, however, this gap in the surviving body of

material evidence can be closed by the architectural historian

of the Middle Ages, who can adduce as supplementary

evidence the record of a group of aisled medieval halls

and barns in timber whose roofs survive.

[ILLUSTRATION]

335. ALBRECHT DÜRER. THE VILLAGE OF KALKREUTH

WATERCOLOR. CA. 1500, KUNSTHALLE, BREMEN BY COURTESY OF THE KUNSTHALLE, BREMEN

ORIGINAL 31.4CM WIDE, 21.6 CM HIGH

Most of the rural architecture of medieval Germany and the medieval Lowlands was destroyed in the ravages of the Thirty Years' War

(1618-1648) but its visual likeness and setting was recorded before that holocaust with great descriptive accuracy in superb watercolors by Dürer

(1471-1528), and in engravings after Peter Breugel the Elder (1525?-1569).

Settlements such as Kalkreuth, and the unnamed Dutch village shown at the right were, as architectural concepts and by their practical function

of virtually the same cast as the hamlet of Ezinge, itself some 1800-1900 years their elder, a reconstruction of which is shown in figure 295.

In all these settlements some of the houses were used to store the harvest, others for the accommodation under one roof of man and beasts.

The earliest surviving structures of this type date from the end of the fifteenth century, but the tradition remained unbroken. The Dutch and

German Lowlands are replete with buildings dating from the 17th and 18th centuries in which the former and his family live and sleep, even

today, under the same roof with the cattle and the harvest—hardly differing in some respects from the way their ancestors had done in the

medieval and protohistoric buildings discussed on p. 23ff.

Jan Jans's Landelijke Bouwkunst in Oost-Nederland, Enschede, 1967, is a fine record of this building tradition and a masterpiece of

architectural drafting. Das Bauernhaus im Deutschen Reich und seinem Grenzgebiete, 1906 (Verband Deutscher Architekten

und Ingenieurvereine) is a primary source for study of rural architecture in Germany. Helm, Das Bauernhaus im Gebiet der freien

Reichstadt Nurnberg, Berlin, 1940, has good architectural analysis of the south German material.