The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V.1.1.. |

| V.1.2. |

| V.1.3. |

| V.1.4. |

| V. 2. |

| V.2.1. |

| 10. |

| 10. |

| V.2.2. |

| V. 3. |

| V.3.1. |

| V.3.2. |

| V.3.3. |

| V. 4. |

| V.4.1. |

| V.4.2. |

| V.4.3. |

| V. 5. |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

| V. 6. |

| V.6.1. |

| V.6.2. |

| V.6.3. |

| V.6.4. |

| V. 7. |

| V.7.1. |

| V.7.2. |

| V.7.3. |

| V.7.4. |

| V.7.5. |

| V.7.6. |

| V. 8. |

| V.8.1. |

| V.8.2. |

| V.8.3. |

| V.8.4. |

| V.8.5. |

| V.8.6. |

| V.8.7. |

| V.8.8. |

| V. 9. |

| V.9.1. | V.9.1 |

| V.9.2. |

| V.9.3. |

| V. 10. |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. |

| V. 11. |

| V.11.1. |

| V.11.2. |

| V.11.3. |

| V. 12. |

| V.12.1. |

| V.12.2. |

| V.12.3. |

| V. 13. |

| V.13.1. |

| V.13.2. |

| V. 14. |

| V.14.1. |

| V.14.2. |

| V. 15. |

| V.15.1. |

| V.15.2. |

| V.15.3. |

| V.15.4. |

| V. 16. |

| V.16.1. |

| V.16.2. |

| V.16.3. |

| V.16.4. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| V.18.1. |

| V.18.2. |

| V.18.3. |

| V.18.4. |

| V.18.5. |

| VI. |

| VI. 1. |

| VI.I.I. |

| VI.1.2. |

| VI.1.3. |

| VI.1.4. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI.2.1. |

| VI.2.2. |

| VI.2.3. |

| VI.2.4. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI.3.1. |

| VI.3.2. |

| VI.3.3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI.4.1. |

| VI.4.2. |

| VI.4.3. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V.9.1

THE MONASTERY'S EDUCATIONAL

TASKS

ROYAL DIRECTIVES

Be it known, therefore, to your devotion pleasing to God, that we,

together with our faithful, have considered it to be useful that the

bishoprics and monasteries entrusted by the favor of Christ to our

control, in addition to the order of monastic life and the intercourse

of holy religion, in the culture of letters also ought to be zealous

in teaching those who by the gift of God are able to learn, according

to the capacity of each individual, so that just as the observance of

the rule imparts order and grace to honesty of morals, so also zeal

in teaching and learning may do the same for sentences, so that

those who desire to please God by living rightly should not neglect

Him also by speaking correctly.[346]

Thus wrote Charlemagne to Abbot Baugulf of Fulda in

a letter drafted by Alcuin, probably in 784 or 785. In a

second issue of the same letter, made out to Archbishop

Angilram of Metz, the emperor adds the admonition:

Do not neglect, therefore, if you wish to have our favor, to send

copies of this letter to all your suffragans and fellow bishops and to

all the monasteries.

The letter from which these sentences are quoted,

Charlemagne's famous epistola de litteris collendis,[347]

is one

of the first of a series of royal directives assigning to the

episcopal and monastic schools of the Frankish kingdom

an active role in education. It is one of the cornerstones of

that programmatic revival of both theological and classical

studies in which Charles took an intense personal interest

and which ushered in the Carolingian Renascence. One of

Charles's specific concerns was the intellectual formation of

the youth who were to form the core of the coming generation

of priests and clerics. In a great circular directive of

789, the admonitio generalis,[348]

he ruled that the children of

free laymen be admitted to the monastic schools, and that

reading classes be established for the young (scolae legentium

puerorum) in which the psalms, music, chant, the calendar

of the religious festivals, grammar, and the creeds of the

faith be taught.[349]

In the pursuit of these as well as the

more general aims of his educational reform, the emperor

systematically enlarged the body of his personal entourage

by adding to the old nucleus of administrative officers of

the Palace distinguished scholars from England, Ireland,

Italy, and Spain, thus setting up at the court itself a school

of learning that could be used as a model for the other

schools in his realm.[350]

The close relationship that existed between so many

medieval rulers and their leading bishops and abbots was

due in no small measure to friendships struck up between

these rulers and their former fellow students and teachers

during their education in monastic schools.[351]

Some monasteries

were understandably proud of these connections, as

may be gathered from a boastful passage in Hariulf's

Chronicle of St.-Riquier:

And as we are speaking of noblemen, never did anyone seek for

anything more distinguished, if he had knowledge of the nobility of

the monks of St.-Riquier: for in this monastery were educated

dukes, counts, the sons of dukes, and even the sons of kings. Every

higher dignitary, wherever located in the kingdom of the Franks,

boasted of having a relative in the abbey of St.-Riquier.[352]

For the original text see Capitulare de litteris collendis, in Mon.

Germ. Hist., Legum II, Capit. I, ed. Boretius, 1883, 78-79. A better

edition is the recent one of Stengel, 1958, 246-54, with important

comments on the authorship of Alcuin and on the date of the letter.

To the authorship question, cf. also Wallach, 1951.

Cf. I, p. 24. On the total collapse of the Early Christian episcopal

school system during the havoc caused by the Germanic migrations, and

the foundation of new schools of learning in the monasteries of Merovingian

and Hiberno-Saxon Europe see Charles W. Jones in his preface to

Bede's Didactic Works (Bedae Opera Didascalica, ed. Jones in Corpus

Christianorum, CXXXIII:B, 1970, and "Bede's Place in Medieval

Schools," Jones, 1973. There also the reader will find an analysis of the

early monastic curriculum and Bede's shares in forming a paradigmatic

program of monastic studies as the composer of what became traditional

Carolingian textbooks.

On the systematic nature of this attempt, besides the general literature

quoted in I, 25 note 45, see commentary of Fleckenstein, 1965,

36ff.

Of members of the royal family educated in monastic schools

Mabillon cites Lothar, the son of Charles the Bald (monastery of St.Germain

at Auxerre); Theoderic III (monastery of Chelles); Louis

IV; Pepin (the father of Charlemagne); and Robert II (monastery of

St.-Denis).

Hariulf, ed. Lot, 1894, 118-19: "Nec enim unquam aliquis de nobilibus

loquens aliud nobilius quaesivit, si sancti Richarii monachorum nobilitas

ei nuntiata fuit. In hoc enim coenobio duces, comites, filii ducum, filii etiam

regum educabantur. Omnis sublimior dignitas, quaquaversum per regnum

Francorum posita, in Sancti Richarii monasterio se parentem habere

gaudebat."

STRESSES LEADING TO DIVISION INTO

INNER AND OUTER SCHOOLS

The stresses that these new educational obligations imposed

upon monastic seclusion were great and must have

been in debate at the second synod of Aachen which passed

the perplexing resolution, "There shall be no other school

in the monastery than that which is used for the instruction

of the future monks."[353]

I have already had occasion to point

out that it could not have been the intent of this ruling to

relieve the monasteries entirely from their share in the intellectual

training of the secular youth, which would have

been a complete reversal of the educational policies promoted

by Charlemagne. Rather it was the expression of a

conflict which in practice was settled by the division of the

monastic educational system into an "inner" and an "outer"

school, the former for the training of the future monks, the

latter for the instruction of those who planned to enter upon

the career of the secular clergy and of such laymen, poor

or noble, whose education was entrusted to monastic

teachers. The former was located in the cloister; the latter

outside it, at a place where it would not intrude on monastic

privacy. This is precisely the manner in which this problem

was settled on the Plan of St. Gall. The inner school is in

the cloister of the Novices,[354]

the Outer School lies between

the House for Distinguished Guests and the Abbot's House,

i.e., in a tract which in all other respects held a transitional

position between the monastic and secular world. Unlike

the schola interior, which remained essentially confined to

elementary learning, the schola exterior developed quickly

into a school for advanced study.[355]

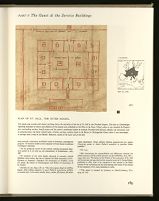

407. PLAN OF ST. GALL. THE OUTER SCHOOL

The simple map reveals with almost startling clarity the centrality of the site of St. Gall in the Frankish Empire. The dicta of Charlemagne

regarding education of clerics and children of free laymen were embodied on the Plan in the Outer School, where it was intended the Empire's

most outstanding teachers should profess and the nation's intellectual leaders be trained. Provided with bedroom cubicles, two classrooms, and

an annexed privy, the Outer School lacks a kitchen; perhaps students dined in the House for Distinguished Guests when it was unoccupied,

or perhaps took a meal in the Monks' Refectory, seated at the lower end of the hall.

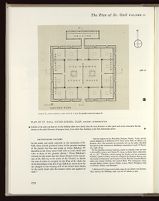

408.A PLAN OF ST. GALL. OUTER SCHOOL. PLAN. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

Cubicles in the aisles and lean-to's of this building reflect more clearly than the room divisions in other guest and service structures the bay

division of the aisled Germanic all-purpose house, from which these buildings of the Plan historically derive.

Explanatory titles identify the cubicles of the Outer School as students' bedrooms, and the large central common hall as the area for teaching

and study. This hall is divided into two classrooms by a freestanding median wall partition. Each is furnished with its own fireplace, and above

these in the roof ridge are lanterns (TESTU) serving as smoke escape and to admit light and air. The small squares in the students' cubicles are

unexplained. It is tempting to interpret them as study tables; but similar squares in the two divisions of the central hall suggest that there

should be openings in the roof to admit light. We have thus reconstructed them in this sense, as dormer windows.

Ibid. Concerning the responsibilities and differences between the

scholae exteriores and the scholae interiores, see Jean Mabillon, Acta, III:1,

1939, xxxiv-xxv. The history of the School of the monastery of St. Gall

and its teachers has been dealt with in a special study by P. Gabriel Meier,

published in 1885. Also to be consulted in this context is De Rijk's

account of the curriculum and the still existing text books of the schools

of the monastery of St. Gall, published in 1963.

DISTINGUISHED TEACHERS

In the ninth and tenth centuries in the monastery of St.

Gall, these schools produced some of the greatest teachers

of the period, the lives and works of whom Ekkehart IV

describes in his Casus sancti Galli with as much detail and

color as those of the greatest abbots.[356]

From Ekkehart's

account we also learn that the Outer School of the monastery

of St. Gall lay to the north of the Church, at almost

the same location it occupies on the Plan of St. Gall; for

in his description of the fire of 937 Ekkehart relates how the

dry shingles of the burning roof of the school were blown

by the north wind onto the church tower and ignited its

roof.[357]

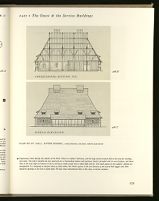

PLAN OF ST. GALL. OUTER SCHOOL. LONGITUDINAL SECTION, NORTH ELEVATION

408.B

408.C

408.D PLAN OF ST. GALL. OUTER SCHOOL. SOUTH ELEVATION

The Outer School could have been built entirely in timber (as was traditional for this type of building) or—because of the high social standing

of many of its occupants, its proximity to the Abbot's House, as well as its need for ample lighting—in the mixed technique which we propose

for the House for Distinguished Guests (figs. 397-399). Masonry would have had the additional advantage of permitting fenestration in the

outer walls of the building.

Adding to this 24-student potential capacity the 12 oblates and novices trained in the Inner School, the 36-student capacity provided for by

facilities on the Plan of St. Gall proves far fewer than the total of 100 students that was Angilbert's pride at St. Riquier ("centum pueros in

hoc sancto loco in scolam congregare studuimus"; Angilberti Abbatis de ecclesia Centulensi Libellus, G. Waitz, ed., Mon.

Germ. hist., Scriptores, XV:1, Hannover 1887, 173-79).

See the chapters on Iso, Marcellus, Radpert, Notker, Tutilo, and the

various Ekkehart's in Ekkeharti (IV.) Casus sancti Galli, ed. Meyer von

Knonau, 1877. The accounts are scattered, but can be easily identified

through the index of persons in Helbling's translation of 1958. Cf. Bruckner,

1938, 28-29.

On the unbroken monastic tradition, master to disciple, from the sixth

to the twelfth century, see Charles W. Jones, in Bedae Opera Didascalia,

ed. cit., 7ff: "Theodore, trained among the Greeks, and his companion

Hadrian, trained in Africa, were led to England by Benedict Biscop, who

was trained at Honoratus' and Cassian's Lerins. Benedict founded Bede's

abbey and trained Ceolfrid, who trained Bede. The subsequent chain,

through Egbert, Albert, Alcuin, Raban, Lupus, Heiric Remigius, leads

to Gerbert, Fulbert, and Berengar."

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||