The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V.1.1.. |

| V.1.2. |

| V.1.3. |

| V.1.4. |

| V. 2. |

| V.2.1. |

| 10. |

| 10. |

| V.2.2. |

| V. 3. |

| V.3.1. |

| V.3.2. |

| V.3.3. |

| V. 4. |

| V.4.1. |

| V.4.2. |

| V.4.3. |

| V. 5. |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

| V. 6. |

| V.6.1. |

| V.6.2. |

| V.6.3. |

| V.6.4. |

| V. 7. |

| V.7.1. |

| V.7.2. |

| V.7.3. |

| V.7.4. |

| V.7.5. |

| V.7.6. |

| V. 8. |

| V.8.1. |

| V.8.2. |

| V.8.3. |

| V.8.4. |

| V.8.5. |

| V.8.6. |

| V.8.7. |

| V.8.8. |

| V. 9. |

| V.9.1. |

| V.9.2. |

| V.9.3. |

| V. 10. |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. |

| V. 11. |

| V.11.1. |

| V.11.2. |

| V.11.3. |

| V. 12. |

| V.12.1. |

| V.12.2. |

| V.12.3. |

| V. 13. |

| V.13.1. |

| V.13.2. |

| V. 14. |

| V.14.1. |

| V.14.2. |

| V. 15. |

| V.15.1. |

| V.15.2. |

| V.15.3. |

| V.15.4. |

| V. 16. |

| V.16.1. |

| V.16.2. |

| V.16.3. |

| V.16.4. |

The daily allowance of bread |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| V.18.1. |

| V.18.2. |

| V.18.3. |

| V.18.4. |

| V.18.5. |

| VI. |

| VI. 1. |

| VI.I.I. |

| VI.1.2. |

| VI.1.3. |

| VI.1.4. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI.2.1. |

| VI.2.2. |

| VI.2.3. |

| VI.2.4. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI.3.1. |

| VI.3.2. |

| VI.3.3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI.4.1. |

| VI.4.2. |

| VI.4.3. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

The daily allowance of bread

The daily ration of bread allowed to each monk was

fixed by St. Benedict:

Let a weighed pound of bread suffice for the day, whether there be

one meal only, or both dinner and supper. . . . But if their work

chance to be heavier, the abbot shall have the choice and power,

should it be expedient, to increase this allowance.[561]

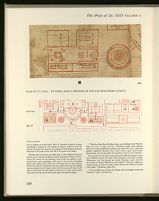

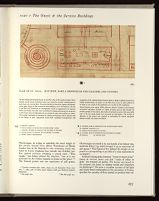

464. PLAN OF ST. GALL. KITCHEN, BAKE & BREWHOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

463.X SITE PLAN

463. PLAN OF ST. GALL. KITCHEN, BAKE & BREWHOUSE FOR PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS

Of three baking and brewing houses on the Plan, that of the monks is largest; but it

includes, besides purely functional space, two rooms for servants' sleeping quarters

and a lean-to for storing flour. Servants attached to houses for pilgrims and distinguished

guests lodged in their respective main buildings, not in the bakeries. The size

of the Bake and Brewhouse for Distinguished Guests is augmented by its separate

larder and kitchen; but when areas used solely for baking and brewing are compared,

it will be seen that the differences in size among the three like facilities are minor.

The essential replication of facilities for baking and brewing, both in function and

in the layout of each, apparently marks both traditional juxtapositions and

recognition of the combined bakery-brewery plan to adapt to efficient service for a

widely varying number of people—on the Plan from as few as twelve pilgrims to

as many as 300 monks if the population ever reached its full complement.

Routes between grain supply (Mills, Mortars, Brewers' Granary) and breweries

of pilgrims' and guests' facilities are highly circuitous and lie right through the

western paradise of the Church. But traffic of burdened servants in this most public

area of the site would hardly have presented an interruption. The sacrifice in

efficiency in this pattern was regained in maintaining the desired segregation

between worldly and claustral activities.

e. PORTER'S LODGING

f. PORCH ACCESS TO HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

i. LODGING, MASTER OF HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS & PAUPERS

h. PORCH ACCESS TO HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS & PAUPERS

9. MONKS' BAKE & BREWHOUSE

10. KITCHEN, BAKE & BREWHOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

30. BREWERS' GRANARY, ETC.

31. HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS & PAUPERS

32. KITCHEN, BAKE & BREWHOUSE FOR PILGRIMS & PAUPERS

28. MORTAR

29. DRYING KILN

Charlemagne, in trying to establish the exact weight of

this pound, learned from Abbot Theodomar of Monte

Cassino that in St. Benedict's own monastery bread was

baked in loaves weighing four pounds and divisible into

four quarter sections, weighing a pound each: "This

weight," the Abbot assures the emperor, "just as it was

instituted by the Father himself, is found at this place."[562]

The Roman pound was the equivalent of 326 grams.

Charlemagne increased it by one fourth of its former size,

sometime before 779, which brought it up an equivalent of

406 grams.[563]

The Synod of 817 defined the weight of one

pound as corresponding to 30 solidi of a value equivalent to

12 denarii.[564]

Adalhard distinguishes between "bread of mixed grain"

(panos de mixtura factos) and that "made of wheat or

spelt" (de frumento uel spelta). The former was issued to

the paupers; the latter, to visiting vassals and clergymen

on pilgrimage.[565]

He gives a complete account of the daily

and yearly bread consumption in the monastery of Corbie,

specifies the quantity of flour needed to produce that volume,

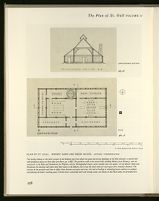

PLAN OF ST. GALL. MONKS' BAKE AND BREW HOUSE. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

465.B LONGITUDINAL SECTION

465.A PLAN

This facility belongs to the third variant of the building type from which the guest and service buildings of the Plan descend: a central hall

with peripheral spaces on three sides (see above, pp. 178ff). The partition wall in the central hall, dividing Bakery from Brewery, was not

structural; in the Bake and Brewhouses for Pilgrims, and for Distinguished Guests, such a divider does not appear. In the Monks' Bake and

Brewhouse the dividing wall allots more floor space to the Bakery, but in fact the work areas for each space were virtually identical. The

location of the partition wall here in effect clears between entryway and oven; the task of loading or unloading loaves could go on without

encumbering the bakers' working space. Certain doors connecting work and storage areas, not shown on the Plan itself, are provided here.

cautions the "keeper of the bread" (custos panis) to make

allowance for the yearly fluctuations in the number of

mouths to be fed by providing for a reasonable surplus of

flour in order not to be caught with a shortage, and he

admonishes him at the same time not to bake more for the

brothers than is needed, "lest what is left over should get

too hard." If this were nevertheless allowed to happen,

the old bread would have to be thrown away, and the

supply of bread replenished.[567]

"Panis libra una propensa sufficiat in die, siue una sit refectio siue

prandii et cenae. . . . Quod si labor forte factus fuerit maior, in arbitrio et

potestate abbatis erit, si expediat, aliquid augere." (Benedicti regula,

chap. 39, ed. Hanslik, 1960, 99-100; ed. McCann, 1952, 94-96; ed.

Steidle, 1952, 234-36).

The qualifying adjective propensa of panis libra una requires comment.

Delatte, 1913, 309 and McCann, 1952, 95 translate "a good pound of

weight;" Steidle, 1952, 234, more convincingly "a well weighed pound

of bread." Hildemar who is closer by eleven hundred years to the source

explains the adjective as follows: Propensa, i.e., praeponderata, i.e.,

mensurata (Expositio Hildemari, ed. Mittermüller, 1880, 437, commentary

to chapter 39 of the Rule). What St. Benedict wished to convey

accordingly—obviously in the interest of equity—would be that the

quantity of dough that went into the making of a loaf of bread should be

measured on the scales rather than left to the guess of the baker.

Whether this was done in the dough stage or after baking will have to

remain a moot question. At Monte Cassino, during the abbacy of Theodomar

(for source see the following note) bread was baked in four-pound

loaves, and accordingly would have to be cut into serviceable

pieces after baking. This could even have been done in the refectory

before the bread was distributed and may indeed have been the simplest

and most logical way of doing it, since even the one-pound loaves would

have to have been cut into smaller portions on the days when several

meals were served, and the bread was eaten in successive stages.

Theodomari epistula ad Karolum, chap. 4, ed. Hallinger and Wegener,

Corp. con. mon., I, 1963, 162-163; "Direximus quoque pondo quattuor

librarum, ad cuius aequalitatem ponderis panis debeat fieri, qui in quaternas

quadras singularum librarum iuxta sacrae textum regule possit diuidi.

Quod pondus, sicut ab ipso padre est institutum, in hoc est loco repertum."

I am puzzled by Semmler's interpreting this difficult passage to mean

that in Monte Cassino, the daily ration of bread, at the time of Abbot

Theodomar, was four pounds per monk (Semmler, 1958, 278). Cf.

the remark of Jacques Winandy on this subject: "Comme il apparait a

simple lecture, le pain de quatre livres devrait être divisé en quatre

parts égales." (Winandy, 1938, 281).

Synodae secundae decr. auth., chap. 22, ed. Semmler, Corp. cons.

mon., I, 1963, 478: Ut libra panis triginta solidis per duodecim denarios

ponderetur.

Consuetudines Corbeienses, chap. 2, ed. Semmler, Corp. con. mon., I,

1963, 372, and translation III, 105.

Ekkehart, in his Benedictiones ad mensas, makes reference to a wide

variety of bread: to "cakes" (torta), "moon-shaped bread" (panem

lunatem), "salted bread" (panem cum sale mixtum), "bread leavened with

egg" (panem per oua leuatum) and "bread leavened with dredge" (panem

de fece leuatum), "bread made of `spelt' " (de spelta), "rye" (triticeum

panem), "wheat" (panem sigalinum), "barley" (ordea panis), "oat"

(panis avena), "fresh bread" and "old bread" (panis noviter cocti and

recens coctus panis), "warm bread" and "cold bread" (calidi panes and

gelidus panis), and lastly, the "morsels and crumbs" (fragmina panum)

left over from each meal. (Benedictiones ad mensas, lines 6-20. See Liber

benedictionum Ekkeharts IV, ed. Egli, 1909, 281-84 and Schulz, 1941.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||