The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V.1.1.. |

| V.1.2. |

| V.1.3. |

| V.1.4. |

| V. 2. |

| V.2.1. |

| 10. |

| 10. |

| V.2.2. |

| V. 3. |

| V.3.1. |

| V.3.2. |

| V.3.3. |

| V. 4. |

| V.4.1. |

| V.4.2. |

| V.4.3. |

| V. 5. |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

| V. 6. |

| V.6.1. |

| V.6.2. |

| V.6.3. |

| V.6.4. |

| V. 7. |

| V.7.1. |

| V.7.2. |

| V.7.3. |

| V.7.4. |

| V.7.5. |

| V.7.6. |

| V. 8. |

| V.8.1. |

| V.8.2. |

| V.8.3. |

| V.8.4. |

| V.8.5. |

| V.8.6. |

| V.8.7. |

| V.8.8. |

| V. 9. |

| V.9.1. |

| V.9.2. |

| V.9.3. |

| V. 10. |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. |

| V. 11. |

| V.11.1. |

| V.11.2. |

| V.11.3. |

| V. 12. |

| V.12.1. |

| V.12.2. |

| V.12.3. |

| V. 13. |

| V.13.1. |

| V.13.2. |

| V. 14. |

| V.14.1. |

| V.14.2. |

| V. 15. |

| V.15.1. |

| V.15.2. |

| V.15.3. |

| V.15.4. |

| V. 16. | V. 16 |

| V.16.1. |

| V.16.2. |

| V.16.3. |

| V.16.4. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| V.18.1. |

| V.18.2. |

| V.18.3. |

| V.18.4. |

| V.18.5. |

| VI. |

| VI. 1. |

| VI.I.I. |

| VI.1.2. |

| VI.1.3. |

| VI.1.4. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI.2.1. |

| VI.2.2. |

| VI.2.3. |

| VI.2.4. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI.3.1. |

| VI.3.2. |

| VI.3.3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI.4.1. |

| VI.4.2. |

| VI.4.3. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V. 16

FACILITIES FOR BAKING

AND BREWING[543]

V.16.1

SYMBIOSIS OF BAKING & BREWING

In large medieval monasteries, the community's baking

and brewing facilities were almost without exception installed

in the same building. This is an intrinsically medieval

arrangement that has no parallels in Greco-Roman life.

Up to the time of the second Macedonian War (200 B.C.197

B.C.), Pliny informs us, the women of Rome used to

bake their bread themselves in their homes,[544]

as had been

customary in the country since the remotest times, and

continued to be among the peasants for ages to come. The

flour was ground in mills operated by mules or by slaves.[545]

From 180 B.C. onward, however, as Rome began to develop

into a megalopolis with multistory apartment houses, the

millers began to usurp the task of baking, because the

architecture of the city and the social conditions of their

inhabitants no longer permitted each family to operate its

own oven. Baking became a professional activity and its

association with milling gave rise to the appearance of

shops, where both of these operations were combined.[546]

A

typical example of this industrial symbiosis is a house in

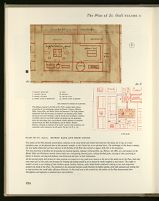

Pompeii, the plan of which is shown in fig. 460. The forward

half of this establishment, facing the street, is a typical

Roman atrium house (1) with the rooms ranged peripherally

around a central court. The rearward part consists

of a court with millstones and baking troughs (2); a baking

oven (3); a room for storing flour (4); a room for kneading

and leavening dough (5); a shop for selling the finished

product (6). This tradition of combining milling and baking

in one and the same shop was not adopted by the Middle

460.X ROME. MUSEO CHIARAMONTI. MONUMENT OF P. NONIUS ZETHUS, OSTIA (LATE IST CENT.)

[courtesy of the Archivo Fotografica dei Musei Vaticani]

This large slab of marble (1.37 × .46 × .75m) imitates the form of a sarcophagus with two rows of conical sockets in the upper surface to receive

incinerary urns. Reliefs illustrate the symbiosis of the trades of milling and baking in Roman life. In the center of a framed panel, the inscription,

resolved of its abbreviations, reads:

PUBLIUS NONIUS ZETHUS AUGUSTALIS

FECIT SIBI ET

NONIAE HILARAE CONLIBERTAE

NONIAE PUBLI LIBERTAE PELAGIAE CONJUGI

PUBLIUS NONIUS HERECLIO

My colleague, Arthur E. Gordon, translates:

Publius Nonius Zethus, an Augustalis, has made [this monument] for himself and nonia hilaria

his fellow freedwoman, [and] Nonia Pelagia, freedwoman of Publius, his wife.—Publius Nonius Hereclio

The donkey in the lyre-shaped wooden trace, the hourglass-shaped mill and its meta and catillus are typical in form (cf. figs. 441. B, 442); an

assortment of standing containers of different capacities are doubtless measures for grain and flour, with additional containers hung on the wall.

A sieve is also depicted, and two or three wooden battens used to level flour or grain to the rim of the container into which it was poured.

The dating of the monument to the end of the 1st century A.D., Gordon informs me, is suggested by both style of writing and Zethus's title,

"AUGUSTALIS," which in the late 1st or early 2nd century was changed to "SEXVIR" or "SEVIR AUGUSTALIS" (see Russel Meiggs,

Roman Ostia, 1960, p. 217, and Wolfgang Helbig's Führer durch die öffentlichen Sammlungen Klassischer Altertümer

in Rom, I, 1963, 245, No. 316.)

power, became a highly specialized professional function

and a privilege jealously guarded by the feudatory who

owned the land and the stream over which the mill was

raised.[547] Baking was dissociated from this craft and entered

instead into a symbiosis with brewing—at least in all those

cases where there was a need for the production of bread

and beer in quantities that required using industrial

techniques, as inevitably was so in a monastic community—

and this association lead to the creation of a new architectural

entity: the monastic bake and brew house.

An impressive example of such a dual-purpose structure,

dating from the end of the eleventh century, is portrayed

on the plan of the waterworks of Christchurch Monastery

(fig. 461), drawn up by the engineer Wibert around 1165.[548]

Measuring approximately 40 by 170 feet (its foundations

can still be traced[549]

), this installation was more than twice

the length of the Monks' Bake and Brew House on the

Plan of St. Gall (fig. 462). Inscriptions tell us that half of

the building was used for brewing (bracium) and the other

half for baking (pistrinum). Precisely when the association

of these two crafts came about historically I do not know.

On the Plan of St. Gall it is an accomplished fact. The

paradigmatic character of the Plan may well have contributed

greatly to the adoption and continuance of this

architectural solution in later monastic planning.

Pliny, Hist. Nat., book XVIII, chap 28, ed. Rackham, V, 1950, 107108:

Pistores Romae non fuere ad Persicum usque bellum annis ab urbe

condita super DLXXX. ipsi panem faciebant Quirites, mulierumque id opus

maxime erat, sicut etiam nunc in plurimis gentium.

This has interesting etymological implications. The term pistrinum

in Classical Latin a designation for mill (from pinsere = to crush),

became in Middle Latin the common term for bakery: cf. below, p. 253.

For a reproduction of the entire plan of Wibert, see I, 70, fig. 52;

for the history of the plan, the literature quoted above, I, 69, notes 16-17.

See Willis, 1868, 149-52; and especially the plan of Christchurch

Monastery as reconstructed by Willis, reproduced between pages 198

and 199.

V.16.2

THE NEED TO MAINTAIN AN ACTIVE

YEAST CULTURE

There are some functional requirements shared by brewing

and baking that could readily dictate that facilities

for the two tasks be installed beneath the same roof.

Both processes depend on the maintenance of an active

yeast culture and the successful completion of a yeast

cycle, each of which requires a temperature that can be

held above 75°F and by consequence, an architectural

ambient capable of furnishing this condition. Yeast is the

indispensable ingredient without which the bread could not

rise nor the beer ferment. The genesis and maintenance of

a yeast culture, or "sponge," must have been a primary

consideration and cause for concern among those whose

duty it was to furnish the daily bread requirements of the

monastery. When the monastery population of St. Gall

was at full complement, nearly 300 loaves daily were to be

produced by the monks' bakery.[550]

In today's terms, the

amount of yeast required to cause such a bulk of flour to

rise must have been considerable—the monks did not have

modern dried yeast, but must have had to maintain and

daily replenish a potent yeast culture and reserve in a good-sized

crock, cauldron or bin, to assure the rising of the new

bread from one day to the next.

The life of a yeast culture is tenacious enough, for the

organism survives even long-term freezing, but it is

quiescent below lukewarm temperatures, and will not instigate

fermentation in beer, nor cause bread to rise steadily

at temperatures much below 80°F. The oven in the bake

house provided that continuance of temperature. Its temperature

rose and declined with the rhythm of the baking

cycle but it was never cold so long as the requirements of

the full community demanded fresh bread daily. For this

reason, the Bake and Brew House maintained a rather

predictable range of temperature throughout the year and

thus afforded a basic precondition for the production of

both bread and beer. To effectively use a large oven such

as the one in the monks' bakery presupposes that it was

warmed, even between firings, by a small banked fire in

its interior. Were it allowed to cool completely and then be

reheated rapidly in daily succession, only a short time would

pass before the oven and its chimney stack would crack

and disintegrate from the effects of too-rapid expansion

and contraction (thermal shock). On the other hand, by

being prewarmed the oven could be heated to temperatures

high enough to bake bread in a relatively short time (at a

probable internal loading-time heat of 700°F) without

straining its thermal tolerance. Keeping the fire alive from

one baking to the next would have made it possible to

"control" the air temperature of the Monks' Bake and

Brew House merely as a side effect of properly tending a

large oven in daily use, thus maintaining an ambient in

which a successful brewing fermentation cycle could be

virtually assured all year round.

V.16.3

DUPLICATION OF DESIGN

AND EQUIPMENT

SUBTLE DIFFERENTIATIONS IN DESIGN

In the monastery shown on the Plan of St. Gall there are

three bake and brew houses, one for the Monks, one for

the House for Distinguished Guests and one for the House

for Pilgrims and Paupers (figs. 462-464). The maker of

the Plan was sensitive to varying demands upon the baking

and brewing facilities in the St. Gall community. While

the layout, design, and equipment of the three bake and

brew houses of the Plan are virtually identical, planned

variations exist in both size and details, in order to accommodate

different traffic through each installation.

The differences are subtle yet persuasively illustrate the

compositional flexibility of this house type and its ability

to adapt with ease to specific needs by an addition to the

principal space of one or several peripheral rooms. The

Bake and Brew House of the Pilgrims and Paupers, with

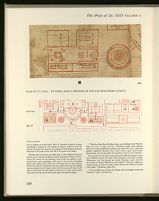

461. CANTERBURY. PLAN OF WATERWORKS FOR CHRISTCHURCH MONASTERY

DRAWN ABOUT 1165

DETAIL SHOWING MONKS' BAKE AND BREW HOUSE

[by courtesy of the Trustees of Trinity College Library, Cambridge University]

The drafters of the Plan of St. Gall considered the association of the crafts of baking and brewing to be both ideal and a practical necessity.

The Christchurch drawing demonstrates, together with many other documentary and archaeological sources, that this association became a

standard trait of monastic architecture in the ensuing two centuries. The plan of the waterworks of Christchurch, Canterbury, shows the

conventual buildings in the state they attained under Bishop Lanfranc (d. 1089), after the Saxon church and monastery were destroyed by fire

in 1067.

The bake and brewhouse of this new monastery was built in the large open court (CURIA), to the north of the claustral compound. It was a

large rectangular building, 40 feet wide and 170 feet long, running with axis parallel to the precinct and city walls bounding the monastery to

the north at a distance of 70 and 100 feet respectively. The building was divided transversely by an internal wall into two unequal sections; the

western and larger of these, covering a surface area of 40 by 110 feet served as Brewhouse (BRACINUM), the eastern and smaller one, measuring

40 by 60 feet, as Bakery (PISTRINUM). A few feet to the east and co-axial with the bake and brewhouse, stood a granary (GRANARIUM)

which, because of its small dimensions, (40 by 40 feet) can only have been a brewers' granary; it is in fact thus referred to in documents of 1803

and 1313 (granarium in bracino, pro novo bracino cum granario; cf. Willis, 1968, 150). Christchurch Monastery had only one bake and

brewhouse. The Plan of St. Gall shows three (figs. 461-463) but the surface area of the Canterbury facility (6,800 square feet) almost equals

the combined surface area of the brewhouses of the Plan (7,120 square feet).

* The entire plan of Canterbury is shown in vol. I, 70, fig. 52.A.

square feet (figs. 463 and 392-393) the smallest of the

installations, serving a constant but modest number of

travellers who received from the monks a fare almost as

simple as their own. On the other hand, the Bake and

Brew House for Distinguished Guests (figs. 396, 400, and

464), although only used occasionally, was at 2,636 square

feet the same size as the Bake and Brew House of the

Monks. This provision of a seemingly too-large space may

be accounted for by the recognition that a large progress

of nobles and their retainers might at times approach the

number of resident monks, with the added complication

of more sophisticated dietary demands of the worldly.

The baking and brewing facilities of the two guest

houses, for example, include cooking facilities, an acknowledgement

of the differing dietary requirements for guests

and monks. Thus, it is seen that the need for three separate

bake and brew houses in the monastery was unavoidable,

because of the different diets involved for the three classes

of men—fuedal lords, paupers and monks—who were to

be served by these separate facilities. Differentiation in the

type and quality of bread is well attested.[551]

It is not unreasonable

to assume that similar distinctions entailed the

production of different types and qualities of beer. In an

article dealing with hops and its history Charles Dimont

points out that "it was the monks who began the classification

of beer by its strength into prima, secunda, and

tertia (which simplified into the categories `X', `XX'

and `XXX', are used even today) and that this tradition

of producing different qualities of beer was carried on in

the universities and colleges which brewed their own

specialities such as `Chancellor', `Audit', and `Archdeacon'."[552]

The Bake and Brew House for Distinguished Guests is

provided with additional space, apparently for storage, in

the form of two lean-to's on the entrance side. Despite the

larger numbers it served, the oven of this installation is

no larger than that in the Bake and Brew House for Pilgrims

and Paupers; at 7½ feet it is smaller in diameter by

one fourth than the monks' oven (dia. = 10 feet), but

therefore more quickly and easily brought to baking heat

after standing cold during periods of disuse. The relation

in the subordinate installations of baking to brewing

facilities is such that the ovens could have served to control

the temperatures for successful brewing, as was likely done

in the Monks' Bake and Brew House, a discussion of which

follows.

See Abbot Adalhard's directives concerning the various types of

bread, below, pp. 257-58. For other dietary distinctions, especially, concerning

the consumption of meat, see I, 275-79; and below, p. 264.

Dimont, 1954, 470; (unfortunately without reference to any historical

sources); the article was brought to my attention by Lynn White.

V.16.4

THE MONKS' BAKE AND BREW HOUSE

We have already dealt with the bake and brew houses for

the pilgrims and paupers and for the distinguished guests

in connection with the two houses to which they are

attached.[553]

The Monks' Bake and Brew House, largest of

the three, remains to be discussed (fig. 462).

The Monks' Bake and Brew House lies south of the

Monks' Kitchen and is connected to the latter by a covered

passageway that allowed the monks to go back and forth

between these two installations without violating the terms

of claustral seclusion. The House is 42½ feet wide and 75

feet long. It has an aisle on each long side and a narrow

lean-to at the east end. The general purpose of the building

is explained, surprisingly in unspecific terms, by a hexameter

running parallel to the entrance side: Here the

brothers' viands shall be taken care of with thoughtful

concern (hic uictus fr̄m̄ cura tract & tur honesta).

The aisle that faces the Kitchen contains two "bedrooms

for the servants" (uernarum repausationes). Uerna, a

term that appears only in this place on the Plan, is probably,

as Leclercq suggests,[554]

the name for a serf, who because he

was born on the monastic domain and had been attached

to the monastery since birth, was treated, if not as a monk,

at least as a brother of inferior rank rather than as a

domestic.

THE BAKERY

The term PISTRINUM

A small vestibule left between the two bedrooms of the

servants gives access to the "brothers' bakery" (pistrinū

fr̄m̄). It occupies the eastern half of the house and its center

space forms an area 22½ feet wide and 32½ feet long.

It should be mentioned in this context that the term

pistrinum is used exclusively as a designation for "bakery"

on the Plan of St. Gall, and never in the sense of "mill,"

its original classical meaning.[555]

The equipment with which

the spaces that carry this designation on the Plan are

furnished offers the proof (figs. 462-464). Hildemar, who

touches on the matter of bake houses in his commentary

of chapter 66 of the Rule, makes some interesting etymological

comments about this term: "Pistrinum," he says,

"is the equivalent of pilistrinum, because in the early days

people used to crush grain with the aid of a pestle (pilo)

for which reason the ancients did not call them grinders

(molitores) but crushers (pistores), i.e., people engaged in

the crushing of grain (pinsores) for there were no mill stones

(molae) in use at that time, but grain was crushed with

pestles."[556]

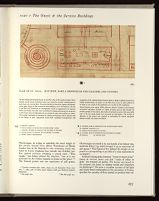

PLAN OF ST. GALL. MONKS' BAKE AND BREW HOUSE

462.X

THE SYMBIOTIC SCHEME IN PLANNING

The efficiency internal to the Plan of St. Gall is nowhere better demonstrated

than in the relationships among the Brewers' Granary, Mortars,

Mills, Drying Kiln, and Monks' Bake and Brewhouse. The traffic patterns

demonstrate with what economy of movement raw material, grain—bulky

and heavy even after threshing—could be moved from the Brewers' Granary

to facilities where it was further refined, and finally into the Brewhouse

where the end product, beer, was produced. Similar efficiency of movement

existed between the Mill, the Bakehouse, and the Monks' Kitchen.

However, planning for isolation of the monks' sanctum takes precedence over

convenience where monastery met the world. See fig. 463.X, p. 256.

SITE PLAN

The makers of the Plan devoted extraordinary attention to the visual detail and verbal instruction for this house, for it lay, in a most

immediate sense, at the physical heart of the monastic complex, as the Church lay at its spiritual heart. The technology of this house is among

the most highly elaborated and least abstract of all facilities of the Plan that existed to support daily life in the monastery.

The close proximity of facilities for processing raw material (grain), refining it (Drying Kiln, 29; Mortar; 28; Mill, 27), and using it in the

Monks' Bake and Brewhouse assumes intense daily use—transporting sheaved grain, sacking threshed grain, carrying it after processing to

bakery or brewery, carrying end products, new bread and new beer, to their destinations.

All the starting points and termini for these processes are found in a very small area relative to the size of the whole site of the Plan. Each day

some major part of the cycles and processes for brewing and baking would be set in motion by monks assigned to such chores. The traffic in

numbers of men, to say nothing of their burdens—grain, buckets, barrows, sacks, baked bread—achieved a density of use and compaction

nowhere else found in the Plan. The planning of the associated facilities would therefore be highly specific, with little assumed and nothing left

to improvisation that would affect efficiency adversely. In this small area of the overall site, the makers of the Plan demonstrated their

thoroughness and ingenuity as administrators and architects.

The term is fascinating, since its shifting values reflect

the entire history of grain preparation from the mortar-and-pestle

stage to the milling stage, and thence by an associative

leap (because bread was often baked near the mill)

from the building in which grain was ground into flour to

the facility where bread was baked.

"Pistrinum quasi pilistrinum, quia pilo antea tundebant granum; unde

et apud veteres non molitores sed pistores dicti sunt; quasi pinsores a pinsendis

granis frumenti; molae enim usus nondum erat, sed granum pilo pinsebant,"

(Expositio Hildemari, ed. Mittermüller, 1880, 607-608).

Layout and equipment

The principal piece of equipment in the Bake House is

the large oven (caminus) which is installed in the southern

aisle of the house directly opposite the entrance. The oven

has a diameter of 10 feet, and is serviced from the main

room of the bakery. This room is furnished with a continuous

course of tables or shelves running in a U-formation

around three of its four walls. The total linear length of

this shelf is 62½ feet. Its depth is 2½ feet. Thus it provides

an ample general work space that could have been used

variously for any number of purposes in the course of

breadmaking.

Next to the oven and in the same aisle with it there is

a trough (alueolus) 12½ feet long and 2½ feet wide. The

space under the lean-to at the east end of the house serves

as a "storage bin for flour" (repositio farinae); this area is

7½ feet wide and 30 feet long. The Plan shows no doors

giving access either to the flour bin or to the room with the

kneading trough—one of the few genuine oversights on

the Plan.[557]

In the axis of the center space, and almost equidistant

from their edges to the shelves that line the room on three

sides, are two rectangles that together form an area 6¼ feet

wide and 10 feet long. A similar but smaller object is found

in the corresponding space in the bakery of the House for

Distinguished Guests. In the bakery of the Hospice for

Pilgrims and Paupers, however, this space is occupied by

the kitchen stove[558]

that seemingly displaces to the brew

house an oblong surface that probably corresponds to the

same pieces found in the center of the bakeries of the other

two houses. Unfortunately the Plan does not provide any

explanatory titles that would enable us to identify the

nature, construction, or function of the objects designated

by these rectangles. This is somewhat surprising because

similar objects situated in the outer aisles are clearly identified

with titles that not only explain their shape or form

(alueolus, trough) but also their function (locus conspergendi,

the place where the dough is mixed; and ineruendae

pastae locus, the place where flour is mingled [with water].)

There is no doubt that the large rectangles in the side

aisles of the bake house were the troughs in which the

dough was first mixed. Good baking practice would require

that the yeast sponge be added to the dough at this beginning

stage, and it is quite possible that after being vigorously

mixed, it was likewise here that the dough was allowed to

enter its first stage of rising. The warmth of the enclosure

near the oven, already fired by a considerable heat, would

significantly aid the rising process in the large mass of

dough.

To convert the bulk of dough into a multitude of loaves

required a different setting: large surfaces sprinkled with

flour where the mass could be broken up, kneaded, divided

and weighed into uniform batches, and shaped into loaves.

All these purposes could have been served by the large

rectangular surfaces in the center of the bakery, or, if these

rectangles were actually troughs, the work could have been

done on the shelves that lined the central space on three

sides. After the loaves were shaped and before they were

placed in the oven for baking, they probably went through

a second stage of rising.[559]

The reconstruction of the equipment used in baking

poses no problem. We have already discussed the oven

together with other heating units shown on the Plan.[560]

Their form was established early and until very recent times

did not undergo any significant changes. The same can

also probably be said about bakers' troughs, a good medieval

example of which is shown in figure 388.

I am inclined to believe that in medieval ovens, the

firing and baking chamber were one and the same unit—as

they were still in the earlier decades of this century in the

bakeries of the German village where I spent my childhood.

There the ovens were heated by wood, as was done

in the Middle Ages. When the right temperature was

reached, the coals were raked out to make room for the

loaves, and the bread was baked as the oven temperature

entered its descending cycle.

While it may not be possible to reconstruct exactly the techniques

the monks used in baking, their methods can have varied but slightly

from those still in use today. For instance, bread baked in small batches

is commonly kneaded after the dough is mixed, but a vigorous mixing

can replace that initial kneading. It is not even necessary that vigorously

mixed dough rise twice, although allowing it to do so assures a finertextured

bread. Any basic variations in the monks' baking methods

probably arose from considerations due to the quantity of bread they

made, rather than from any special mysteries inherent in breadmaking.

The daily allowance of bread

The daily ration of bread allowed to each monk was

fixed by St. Benedict:

Let a weighed pound of bread suffice for the day, whether there be

one meal only, or both dinner and supper. . . . But if their work

chance to be heavier, the abbot shall have the choice and power,

should it be expedient, to increase this allowance.[561]

464. PLAN OF ST. GALL. KITCHEN, BAKE & BREWHOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

463.X SITE PLAN

463. PLAN OF ST. GALL. KITCHEN, BAKE & BREWHOUSE FOR PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS

Of three baking and brewing houses on the Plan, that of the monks is largest; but it

includes, besides purely functional space, two rooms for servants' sleeping quarters

and a lean-to for storing flour. Servants attached to houses for pilgrims and distinguished

guests lodged in their respective main buildings, not in the bakeries. The size

of the Bake and Brewhouse for Distinguished Guests is augmented by its separate

larder and kitchen; but when areas used solely for baking and brewing are compared,

it will be seen that the differences in size among the three like facilities are minor.

The essential replication of facilities for baking and brewing, both in function and

in the layout of each, apparently marks both traditional juxtapositions and

recognition of the combined bakery-brewery plan to adapt to efficient service for a

widely varying number of people—on the Plan from as few as twelve pilgrims to

as many as 300 monks if the population ever reached its full complement.

Routes between grain supply (Mills, Mortars, Brewers' Granary) and breweries

of pilgrims' and guests' facilities are highly circuitous and lie right through the

western paradise of the Church. But traffic of burdened servants in this most public

area of the site would hardly have presented an interruption. The sacrifice in

efficiency in this pattern was regained in maintaining the desired segregation

between worldly and claustral activities.

e. PORTER'S LODGING

f. PORCH ACCESS TO HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

i. LODGING, MASTER OF HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS & PAUPERS

h. PORCH ACCESS TO HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS & PAUPERS

9. MONKS' BAKE & BREWHOUSE

10. KITCHEN, BAKE & BREWHOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

30. BREWERS' GRANARY, ETC.

31. HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS & PAUPERS

32. KITCHEN, BAKE & BREWHOUSE FOR PILGRIMS & PAUPERS

28. MORTAR

29. DRYING KILN

Charlemagne, in trying to establish the exact weight of

this pound, learned from Abbot Theodomar of Monte

Cassino that in St. Benedict's own monastery bread was

baked in loaves weighing four pounds and divisible into

four quarter sections, weighing a pound each: "This

weight," the Abbot assures the emperor, "just as it was

instituted by the Father himself, is found at this place."[562]

The Roman pound was the equivalent of 326 grams.

Charlemagne increased it by one fourth of its former size,

sometime before 779, which brought it up an equivalent of

406 grams.[563]

The Synod of 817 defined the weight of one

pound as corresponding to 30 solidi of a value equivalent to

12 denarii.[564]

Adalhard distinguishes between "bread of mixed grain"

(panos de mixtura factos) and that "made of wheat or

spelt" (de frumento uel spelta). The former was issued to

the paupers; the latter, to visiting vassals and clergymen

on pilgrimage.[565]

He gives a complete account of the daily

and yearly bread consumption in the monastery of Corbie,

specifies the quantity of flour needed to produce that volume,

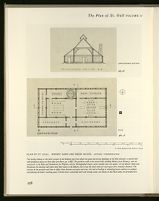

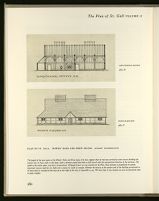

PLAN OF ST. GALL. MONKS' BAKE AND BREW HOUSE. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

465.B LONGITUDINAL SECTION

465.A PLAN

This facility belongs to the third variant of the building type from which the guest and service buildings of the Plan descend: a central hall

with peripheral spaces on three sides (see above, pp. 178ff). The partition wall in the central hall, dividing Bakery from Brewery, was not

structural; in the Bake and Brewhouses for Pilgrims, and for Distinguished Guests, such a divider does not appear. In the Monks' Bake and

Brewhouse the dividing wall allots more floor space to the Bakery, but in fact the work areas for each space were virtually identical. The

location of the partition wall here in effect clears between entryway and oven; the task of loading or unloading loaves could go on without

encumbering the bakers' working space. Certain doors connecting work and storage areas, not shown on the Plan itself, are provided here.

cautions the "keeper of the bread" (custos panis) to make

allowance for the yearly fluctuations in the number of

mouths to be fed by providing for a reasonable surplus of

flour in order not to be caught with a shortage, and he

admonishes him at the same time not to bake more for the

brothers than is needed, "lest what is left over should get

too hard." If this were nevertheless allowed to happen,

the old bread would have to be thrown away, and the

supply of bread replenished.[567]

"Panis libra una propensa sufficiat in die, siue una sit refectio siue

prandii et cenae. . . . Quod si labor forte factus fuerit maior, in arbitrio et

potestate abbatis erit, si expediat, aliquid augere." (Benedicti regula,

chap. 39, ed. Hanslik, 1960, 99-100; ed. McCann, 1952, 94-96; ed.

Steidle, 1952, 234-36).

The qualifying adjective propensa of panis libra una requires comment.

Delatte, 1913, 309 and McCann, 1952, 95 translate "a good pound of

weight;" Steidle, 1952, 234, more convincingly "a well weighed pound

of bread." Hildemar who is closer by eleven hundred years to the source

explains the adjective as follows: Propensa, i.e., praeponderata, i.e.,

mensurata (Expositio Hildemari, ed. Mittermüller, 1880, 437, commentary

to chapter 39 of the Rule). What St. Benedict wished to convey

accordingly—obviously in the interest of equity—would be that the

quantity of dough that went into the making of a loaf of bread should be

measured on the scales rather than left to the guess of the baker.

Whether this was done in the dough stage or after baking will have to

remain a moot question. At Monte Cassino, during the abbacy of Theodomar

(for source see the following note) bread was baked in four-pound

loaves, and accordingly would have to be cut into serviceable

pieces after baking. This could even have been done in the refectory

before the bread was distributed and may indeed have been the simplest

and most logical way of doing it, since even the one-pound loaves would

have to have been cut into smaller portions on the days when several

meals were served, and the bread was eaten in successive stages.

Theodomari epistula ad Karolum, chap. 4, ed. Hallinger and Wegener,

Corp. con. mon., I, 1963, 162-163; "Direximus quoque pondo quattuor

librarum, ad cuius aequalitatem ponderis panis debeat fieri, qui in quaternas

quadras singularum librarum iuxta sacrae textum regule possit diuidi.

Quod pondus, sicut ab ipso padre est institutum, in hoc est loco repertum."

I am puzzled by Semmler's interpreting this difficult passage to mean

that in Monte Cassino, the daily ration of bread, at the time of Abbot

Theodomar, was four pounds per monk (Semmler, 1958, 278). Cf.

the remark of Jacques Winandy on this subject: "Comme il apparait a

simple lecture, le pain de quatre livres devrait être divisé en quatre

parts égales." (Winandy, 1938, 281).

Synodae secundae decr. auth., chap. 22, ed. Semmler, Corp. cons.

mon., I, 1963, 478: Ut libra panis triginta solidis per duodecim denarios

ponderetur.

Consuetudines Corbeienses, chap. 2, ed. Semmler, Corp. con. mon., I,

1963, 372, and translation III, 105.

Ekkehart, in his Benedictiones ad mensas, makes reference to a wide

variety of bread: to "cakes" (torta), "moon-shaped bread" (panem

lunatem), "salted bread" (panem cum sale mixtum), "bread leavened with

egg" (panem per oua leuatum) and "bread leavened with dredge" (panem

de fece leuatum), "bread made of `spelt' " (de spelta), "rye" (triticeum

panem), "wheat" (panem sigalinum), "barley" (ordea panis), "oat"

(panis avena), "fresh bread" and "old bread" (panis noviter cocti and

recens coctus panis), "warm bread" and "cold bread" (calidi panes and

gelidus panis), and lastly, the "morsels and crumbs" (fragmina panum)

left over from each meal. (Benedictiones ad mensas, lines 6-20. See Liber

benedictionum Ekkeharts IV, ed. Egli, 1909, 281-84 and Schulz, 1941.

A single cycle of firing and baking

If we presume that St. Benedict's allowance of a daily

pound of bread for each monk applied to the monastery's

serfs as well, the monks' bakery on the Plan of St. Gall

would have to have been capable of producing 250 to 270

pounds of bread per day.[568]

An analysis of the dimensions

of its oven and the amount of space required for this output

discloses that this volume of bread could be produced in a

single cycle of firing and baking.[569]

A passage in Ekkehart's Casus sancti Galli, which has

consistently been misconstrued, reads that the monastery

of St. Gall had an oven (clibanum) capable of baking a

thousand loaves of bread at once and a bronze kettle

(lebete eneo) and drying kiln (tarra avenis) capable of

holding one hundred bushels of oats.[570]

This is not a

statement of fact, but a passage in a speech by Abbot

Solomon III, which Ekkehart himself refers to as "boastful"

and "fraudulent."[571]

I am relying on the calculation of my friend Thomas Tedrick who

assures me that an oven 10 feet in diameter on the inside is capable of

baking 356 loaves of bread, each weighing one pound, in a single process

of baking if all available space is utilized and the loaves, after their

expansion during baking, are allowed to touch each other. After some of

the oven's space has been subtracted for wall thickness and more for a

narrow margin of space to be allowed between the loaves to prevent them

from sticking together, the dimensions of this oven turn out to have been

planned to meet exactly the daily baking requirements of the monks and

serfs of the monastery shown on the Plan of St. Gall.

First quoted as a fact by Keller (1844, 14), but without exact

reference to the place and context in which this statement occurred,

and subsequently repeated by scholars who failed to look up the original

source. Even Bikel (1914, 119) is guilty of that error by omission.

See Ekkeharti (IV.) Casus sancti Galli, chap. 13, ed. Meyer von

Knonau, 1877, 51-54; ed. Helbling, 1958, 40.

THE BREWERY

From Babylon and Egypt to St. Columban

Beer is a malted beverage that was brewed in Babylon and

Egypt from primordial times[572]

but it was held in low esteem

by the wine-loving Greeks and Romans, and because of

this deeply rooted cultural aversion made no imprint whatsoever

on early monastic life, from the literature of which

the terms cerevisa or celia are wholly absent. The drink

acquired significance, however, as monachism spread into

the north and west of Europe where beer has been a

traditional beverage since the remotest times and where wine

was as yet not made in sufficient quantities to take care of

all of the needs of the monks.

Pliny describes caelia, cerea and cerevisia as words of

Celtic origin denoting beverages drunk in his days in

Spain and in Gaul and remarks that its froth was used by

the women of these countries as a cosmetic for the face.[573]

The terms do not occur at any place in the Rule of St.

Benedict. The earliest evidence of the consumption of beer

in a monastic context, to the best of my knowledge, is a

passage in the Life of St. Columban, (543-615) written by

the monk Jonas of Bobbio (ca. 665) which relates that in the

days of Columban, beer was served in the refectory of the

monastery of Luxeuil (founded by St. Columban ca. 590).

In this account cervisia is referred to as a beverage "which

is boiled down from the juice of corn or barley, and which

is used in preference to other beverages by all the nations

in the world—except the Scottish and barbarian nations who

inhabit the ocean—that is in Gaul, Britain, Ireland, Germany

and the other nations, who do not deviate from the

custom of the above."[574]

PLAN OF ST. GALL. MONKS' BAKE AND BREW HOUSE. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

465.D LONGITUDINAL SECTION

465.C NORTH ELEVATION

The length of the main space of the Monks' Bake and Brew house, 67½ feet, suggests that its roof was carried by seven trusses dividing the

interior into six bays, each 11 feet deep. Such a division would have been in full accord with the asymmetrical location of the entrance. The

width of the center space, 22½ feet is conventional. Although louvers are not marked on the Plan, their presence is postulated for purely

functional reasons (need for air, light and a means for smoke to escape). Whether the lean-to at the eastern end of the building terminated on

tie beam level or reached all the way up to the ridge of the roof, is impossible to say. We have kept it low, because we saw no functional need

to take it higher.

For brewing in the ancient Near East and in Egypt, see Arnold,

1911; Lutz, 1922; Huber, 1926, and Bücheler, 1934. For brewing in the

early Middle Ages, see Heyne, II, 1901, 334. For brewing in St. Gall, see

Knoblauch, 1926; and Joseph Müller, 1941. An informative article on

domestic brewing and brewing utensils in English, by Allan Jobson, will

be found in Country Life, March 4, 1949; for pictures of a reconstructed

medieval brewhouse and its equipment, see G. Bernard Wood in

Country Life, July 2, 1953.

Of great interest in this context is the ancient Brewery of Queen's

College Oxford, a description of which will be found in the article

"Brewing" of the Encyclopedia Britannica.

Pliny, Hist. Nat., Book XXII, chap. 82; ed. W. H. S. Jones (The

Loeb Classical Library), VI London-Harvard, 1951, 408-411.

Vita Sancti Columbani Abbatis, auctore Jona Monacho Bobiensi, ed.

Jean Mabillon, Acta Sanctorum Ordinis S. Benedicti, 3rd ed., Paris, 1935,

16: "Cum hora refectionis appropinquaret, & minister Refectorii cervisiam

administrare conaretur (quae ex frumenti vel hordei succo excoquitur,

quamque prae ceteris in orbe terrarum gentibus praeter Scoticas & Barbaras

gentes quae Oceanum involunt usituntur, idest Gallia, Britannia, Hibernia,

Germania, caeteraeque qua ab eorum moribus non desciscunt) vas quod

tybrum nuncupant, minister ad cellarium deportat, & ante was quo cervisia

condita erat apponit . . ."

Basic procedures in the making of beer

Beer is brewed in a number of different ways, resulting

in a variety of different brews. The manufacture of all of

them has certain basic steps in common:

1. First, grain, usually barley, is "malted," i.e., allowed

to steep in water until it begins to germinate, and starches

in the grain undergo chemical changes that produce

sugars.

2. Then the malted grain is mashed and infused in

gradually heated water, the temperatures of which are

raised in stages to 165° or 175°F. This heating arrests the

germination of the malted grain and results in a liquid

known as wort (sweet wort) which retains the natural

sugars and enzymes generated by infusion.

3. After completion of the infusion process the wort is

transferred to a kettle and to it is added the blossoms of

hops that give beer its characteristic aroma and flavor. This

mixture of wort and hops (hopped wort) is boiled for about

two hours.

4. After this operation is completed the liquid is

cleansed by straining out the hops and sediments, and

filtered into a cask or trough for cooling. At this point

the yeast is added to the wort and fermentation begins.

Beer may be fermented in a variety of ways, but until

relatively recently, the process favored on the Continent

was that of top fermentation, in which the yeast rises to

the top of the fermentation vat and is there skimmed off

when fermentation is complete. Some beers can be drunk

immediately after fermentation is complete. Others, particularly

those made by top fermentation are stored in

casks from two or three weeks to six months. During the

storage period the beer brightens and becomes charged

with carbon dioxide. Beer fermented in this way is stored

in an ambient of 58°-70°F, a condition entirely consonant

with temperatures that could be maintained both in the

Monks' Brew House where fermentation of the beer was

instigated, and in the great cellar used for wine and beer

storage (see I, 292-307).

Layout and equipment

On the Plan of St. Gall, the monks' brewery lies in the

western half of the Monks' Bake and Brew House (fig.

462). It covers the same area as the bakery, but has no

lean-to on the narrow end of the building. The space in

which it is accommodated is marked by the title "Here let

the beer for the brothers be brewed" (hic fr̄ībus conficiat

ceruisa). It is reached from the monks' bakery and has no

separate access from the outside. The monks' brewery is

furnished with all the equipment needed in brewing: a

stove with four ranges for heating water and boiling wort

with hops. The stove is identical in design with the large

stove in the Monks' Kitchen.[575]

Around that stove four

round objects are shown—vats or cauldrons, no doubt,

wherein the grain was steeped for malting, and infusion

was done. These could have consisted either of simple

wooden tubs, or of heatable cauldrons or of a combination

of both, and may have been in shape or construction like

any of those shown in figure 387 and 390. The south

aisle of the brew house serves as a cooler. It is furnished

with two troughs and a vat, explained by the inscription

"Here let beer be cooled" (hic col&ur celia). Here the

yeast was added to the worted liquid and fermentation

began. From the cooling troughs unquestionably the beer

was moved to casks in the cellar, and allowed to finish

fermenting and clearing, before it was brought to the table.

Replacement of wine by beer in ratio of 1:2

We have already drawn attention to the fact that wine was

the traditional monastic beverage, beer only a substitute,

and that a ruling of the Synod of 816 directed that if

shortages in wine had to be made up for by beer, this should

be done in the ratio of 1:2.[576]

Therefore, if such an emergency

arose, beer would have had to be available in considerable

quantities. Abbot Adalhard of Corbie allows each

visiting pauper a ration of 1.4 liters of beer per day.[577]

If

this same amount were issued to the monks and the serfs

of the monastery, this would mean that the monastery

shown on the Plan of St. Gall issued 350 to 400 liters a

day. Over a period of time, this practice would have required

storing a considerable volume of beer. Unlike wine,

beer is not a seasonal product, but can be manufactured

continuously, and in the monastery it probably was manufactured

continuously, like the bread in the nearby bakery.

Today the brewing of beer is almost exclusively in the

hands of commercial firms. Throughout the major part of

the Middle Ages it was a small-scale domestic operation.

Before the twelfth and thirteenth centuries when brewing

first emerged as a commercial venture, the monastery was

probably the only institution where beer was manufactured

on anything like a commercial scale.

Use of hops as a flavoring agent

The explanatory titles of the various bake and brew

houses of the Plan of St. Gall contain no direct reference to

the use of hops as a flavoring agent in the production of

beer, but it is quite possible that a tacit allusion to this

plant is hidden in the second half of the title which defines

the Brewers' Granary as the place "where the cleansed

grain is kept and where what goes to make beer is prepared"

(granarium ubi mandatū frumentum seru&ur & qd ad

ceruisā praeparatur).[578]

This granary is ideally located, in

the middle between the Monk's Brewhouse and their

Drying Kiln—which in addition to serving as a facility for

parching fruit and grapes, could also have performed the

function of a monastic oast house.[579]

PLAN OF ST. GALL. MONKS' BAKE AND BREW HOUSE. AUTHORS' RECONSTRUCTION

465.F WEST ELEVATION

465.E EAST ELEVATION

At the western end of the building the aisles and the center space terminated in a straight line. Under such conditions, the design of the

terminal truss, together with all of its secondary members and infillings, would have been visible for the entire width and height of the structure.

At the opposite end, because of the presence of a lean-to, only the triangular wall section above tie beams could have been exposed to the

exterior. The design of these two sides of the building has a close parallel in the Physicians' House (figs. 413.C and D) except for the different

placement of the entrance.

There is sufficient evidence to make it clear that the

hopping of beer was in the early Middle Ages a widespread

monastic practice north of the Alps. In his Administrative

Directives of A.D. 822 Abbot Adalhard of Corbie addresses

himself in detail to the procedures that should control the

tithing of hops and their distribution among the various

monastic officials placed in charge of brewing.[580]

He makes

it a point to exempt the miller from making malt or from

growing hops (nec braces faciendo nec humulonem) because

of the weight of his other duties.[581]

Consuetudines Corbeienses, chap. 5, 25; ed. Semmler, Corp. Cons.

mon., I, 1963, 400 and translation, III, 117.

Ural-Altaic origins

The origins of the use of hops as a constituent ingredient

in brewing is an intriguing literary and linguistic subject.

E. L. Davis, and others before him, have drawn attention

to the importance given to hops in the folklore of Finland

and the Caucasus region and believed to reflect a cultural

heritage of great antiquity. They thus inferred that hops

were used as an ingredient for beer in the northeast and

east of Europe long before this practice was introduced in

western Europe.[582]

In a more recent study, Arnald Steiger

traced the origin of the custom even further eastward.

The earliest word forms for hops (best reflected in Old

Turkish qumlaq), Steiger contends are found in a variety of

Ural-Altaic languages of great antiquity. From there the

term migrated west into the orbit of the Slavic languages

(Old Slavic chǔmelǐ and through the latter into the North

Germanic language groups (Old West Nordic humili) which

transmitted it to the Salian and Ripuarian Franks (Middle

Latin humelo . . . leading to Modern French houblon). This

evidence, Steiger argues, suggests that the practice of

hopping beer originated in Central Asia and was transmitted

from there to Northern and Western Europe by the

Slavs along the linguistic channels indicated by the

migration of the word for hops.[583]

The Greeks knew the plant only in its uncultivated state

(and under a different name), but the Romans grew it in

their vegetable gardens and used it as a flavoring agent for

salads.[584]

E. L. Davis, 1956, unpublished thesis, Dept. of Botany, Washington

University. Numerous references to the use of hops in brewing beer are

found in the Finnish epic poem Kalevala, a typical example of which, as

rendered in the prose edition by Francis Peabody Magoun, Jr., 1963, 137,

reads as follows:

"Then the mistress of North Farm, when she heard about the origin of

beer, got a big tub of water, a new wooden tub half full, with barley

enough in it and a lot of hop pods. She began to boil the beer, to prepare

the strong liquor in the new wooden cask, in the birchwood keg."

The Kalevala, song 20, lines 421-26

(The Finnish word for "hops" used in the Kalevala is humala).

On the early west European history of hop cultivation, its diffusion

from the territory of the Franks to the territory of the Bajuvarians and

other Germanic tribes, see Victor Hehn, 1874, 411ff (or any of the many

later editions of this important work). The subject is also discussed in

Heyne, II, 1901, 72, and 341. To the kindness of Lynn White I owe the

knowledge of the following more recent literature: Steiger, 1954 (a well-documented

linguistic study); Ditmond, 1954 (good, but exasperating

reading since its author, obviously well-informed, takes as much pain in

hiding the sources of his learning as he must have taken in acquiring it);

Darling, 1961 (deals primarily with conditions in England, but has a good

bibliographical section); Macdonagh, 1964 (stresses the antibiotic effects

of hops permitting preservation and transportation of beer); Birch 1965

(useless).

Earliest medieval mention of hops

Probably the earliest medieval mention of the plant is a

charter of A.D. 768 in which King Pepin the Short deeded

some hop gardens (homularia) to the monastery of St.Denis.[585]

During the reign of Charlemagne and Louis the

Pious the evidence multiplies. Abbot Ansegis (823-833)

lists amongst the annual deliveries to be made to the Abbey

of St.-Wandrille (Fontanella): "beer made from hops, as

much as is needed" (sicera homulone quantum necessitas

exposcit).[586]

Hops were part of the revenues paid to the

Abbey of St.-Germain-des-Prés from several outlying

possessions (The fiscs of Combs-la-Ville, of Marenil and of

Boissy),[587]

and the plant is mentioned in various places in

deeds of the abbey of Freisingen, dating from the reign of

Louis and Pious as well as from later periods.[588]

All of these references to the plant, in conjunction with

the detailed directives issued by Abbot Adalhard on the

tithing and internal distribution of hops leave no doubt

that, at the time of Louis the Pious, hops had become a

customary ingredient of beer produced in the transalpine

monasteries of the Empire.[589]

One of the beneficial effects of its admixture, besides the

distinctive flavor it imparted to the brew, was that owing

to its antibiotic properties it prolonged the life of beer

considerably over that of the older and more perishable

ale.[590]

This was of great importance when storage in bulk

was required and where transportation was involved—as

they inevitably were in the beer economy of a monastic

settlement.

Contemporary sources make it quite clear that not

all the beer consumed by the monks and their serfs

was brewed inside the monastic enclosure. All the larger

outlying agricultural holdings, and many of the smaller

ones, had their own facilities for brewing. The delivery of

a tenth of their home-brewed beer was a standard procedure

in the tithing of tenants. Records of these tithes

appear in the deeds of the monastery of St. Gall from as

early as the middle of the eighth century. Some of the

tenants had licenses to set up taverns, and many of these

continued to pay for their tenancy through the delivery of

beer even later, when all other forms of tithing in naturalia

had been abolished.[591]

Mon. Germ. Hist., Dipl. Karol., I, Hannover 1906, 38-40, No. 28.

Donation, dated Sept. 768, of the forest of Iveline to the Abbey of St.

Denis by Pepin: et in Ulfrisiagas mansos duos et Humlonarias cum integritate.

Uisiniolo Similiter, Ursionevillare similiter.

Constitutio Ansigis Abbatis, in Gesta S.S. Patr. Font. Coen., ed.

Lohier-Laporte, 1936, 121; and trans. by Charles W. Jones, III, 125-26.

In the Polyptych of Abbot Irminon the plant is referred to as humulo,

humelo, umlo, and fumlo. See paragraph HOUBLON by M. B. Guérard,

in Polyptyque de L'Abbé Irminon, I, Paris 1844, 714 and the passages

there referred to.

England resisted its use throughout most of the Middle Ages,

retaining preference for the traditional ale, which was brewed without

hops. Cf. Macdonagh, 1964, 531.

"Ale had to be drunk very soon after brewing; beer did not turn

acid and sour for some while, the length of time depending mainly on

the amount of hops used." Macdonagh, loc. cit.

Work in the bake and brew house:

a privilege of the monks

Working in the Bake and Brew House was one of the

manual labors traditionally required of the brothers, and

so specifically stipulated both in the preliminary and the

final resolutions of the First Synod of Aachen (816).[592]

The

brothers apparently liked this work, since one of the protests

lodged before the emperor in the same year by the

monks of Fulda about the hardships brought upon them

by Abbot Ratger's excessive building program included the

complaint that it deprived them of their traditional right

to work in the Bake and Brew House (pistrinum and brati-

arium).[593]

It does not seem far-fetched to suppose that the

constant warmth of the bakery attracted the brothers to

the chore of breadmaking. During the long northern winters,

when all warmth was leached from the cloister, the

bakery was one of the few places in the community a monk

could work in comfort of body as well as of soul, and

surrounded by the incomparable fragrance of new bread.

Statuta Murbacensia, chap. 4, ed. Semmler, Corp. cons. mon., I,

1963, 443: "Quinto, ut fratres in coquina, in pistrino et ceteris officiis

artium propiis manibus laborent et uestimenta sua lauent." For the full text

of chapter 4 of the Final Resolutions, see I, 23 n.31.

For the Bake and Brew House of the Hospice for Pilgrims and

Paupers, see above, pp. 151-53; for that of the Distinguished Guests,

above pp. 151-53.

In the treatment that follows, I am greatly indebted to my editor,

Lorna Price, whose experience in baking bread has brought substance

and life to the discussion on this subject. Her interesting argument

concerning the functional interdependence of baking and brewing appears

to me a more persuasive explanation of the traditional medieval association

of these two crafts under the same roof than I have found anywhere

else in the literature. I regret that Lorna Price does not have equally rich

experiences in the art of home brewing; otherwise my discussion of the

brewing facilities would be less thin than it is in its present form.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||