Layout and function

The general purpose of the House for Distinguished

Guests is defined by a hexameter which reads:

domus

Haec quoque hospitibus parta est quoque suspicientis[311]

This building, too, serves for the reception of guests

The conjunction quoque suggests that the building holds a

position of secondary importance with regard to another

facility for guests, which can only be the Hospice for Pilgrims

and Paupers. The modest slant of this verse is obviously

a reflection of the warning given by St. Benedict

that the hospitality accorded to the poor lies on a higher

plane of religious devotion than that extended to the rich.[312]

But the profuse attention lavished on the internal layout of

the House for Distinguished Guests tends to defy this

thought.

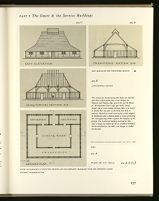

The House is 67½ feet long and 55 feet wide. It has as its

principal room a large rectangular hall, which its explanatory

title defines as the "dining hall of the guests" (domus

hospitū ad prandendum). Access to this is gained through a

"vestibule" (

ingressus) which lies in the middle of the

southern aisle of the house. The dining hall has in its center

a large quadrangular "fireplace" (

locus foci) and in the

corners, ranged all around the circumference, benches and

"tables" (

mensae), plus two "cupboards" (

toregmata[313]

) for

the storage of cups and tableware. Under the lean-to's at

each of the narrow ends of the house there are the "bedrooms"

for the distinguished guests (

caminatae cum lectis),

four in all, each furnished with its own corner fireplace and

its own projecting privy (

necessariü). The rooms to the left

and right of the entrance in the southern aisle of the house

serve as "quarters for the servants" (

cubilia seruitorum),

while two corresponding rooms in the northern aisle are

used as "stables for the horses" (

stabula caballorum). Their

cribs (

praesepia) are arranged against the outer walls. A

small vestibule between the two stables gives access to a

covered passage that leads to a large privy (

exitus neces-

sarius). The latter covers a surface area of 10 by 45 feet and

is furnished with no fewer than eighteen toilet seats—an

indication of the extraordinary sanitary precautions that,

at the time of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious, must have

been taken for the persons who traveled in the emperor's

immediate entourage.

[314]

I have already drawn attention to the fact that the stables

for the horses have no direct access from the exterior. The

entire house has only one entrance, and in order to reach

their stables the horses had to be led through the central

dining hall. This suggests that all the rooms of the house

were on ground level and that the floor of the center room

was made of stamped clay rather than of a boarding of wood.

The large open fireplace in the center of the dining room

makes it unequivocably clear that this house was not a

double-storied structure.[315]

[ILLUSTRATION]

406.B

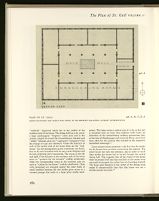

By making the center hall of this building 45 feet wide by 60 feet long, the drafters of the Plan pushed the structural capabilities of the aisled

Germanic all-purpose house to its limits. Spans of 45 feet, rare even in church construction, were unheard-of in domestic architecture. We

know of only one other medieval building of even comparable dimensions: the barn of the abbey grange of Parçay-Meslay, France (figs. 352-355)

at a width of 80 feet. But the vast roof of that barn is supported, not by the traditional two, but by four rows of freestanding inner posts.

We do not believe that the roof of the House for Knights and Vassals could have been supported successfully by less posting and have therefore

introduced in our reconstruction two additional rows of posts, that reduce the center span of the inner hall from 45 to a more conventional

27 feet.

Incorporating the doubled rows of posting is not in conflict with methods of architectural rendering employed by the drafters of the Plan.

They were not concerned with constructional details, but primarily with establishing the boundaries of each building on the site in terms of its

function and its components. The size of a royal retinue—including its servants, grooms, bodyguard, as well as the principals themselves—

justifies the tentative identification of this house.

In this, as in other buildings of the Plan, details of construction engineering were left to be resolved by the ingenuity of a master builder who

would determine in what ways a building conceived for the purpose of housing up to 40 men and 30 horses, and their attendants, could be

realized as functional architecture. The interaction of planners with builders is elsewhere attested on the Plan, wherever features obviously

intended and needed are absent: staircases, doors and windows, and others (see I. 13, 65ff).

The main point of interest, we believe, in our investigation of this particular building is that the prevailing building type of the Plan of St. Gall,

the three-aisled hall—without loss of the essence of its character—adapts with ease and dignity and possibly with some elegance, to a building of

relatively inordinate size through the device of adding an aisle between the central main space of the nave, and each of the lean-to side aisles.

In effect, a five-aisled hall is thus formed (see fig. 354.A, B, Parçay-Meslay, and Les Halles, Côte St. André, Isère, France).