VI. 3

LAYOUT OF THE BENEDICTINE

MONASTERY FROM

THE LATE ELEVENTH TO THE

THIRTEENTH CENTURY

VI.3.1

ENGLISH SOURCES

All of the monasteries discussed on the pages which

follow are English, because in England the archaeological

record is more reliable and richer than elsewhere in

Europe. The suppression of monastic life by Henry VIII

from 1538 onward halted rebuilding; and the existing or

excavated remains reflect the original dispositions more

closely than do the Continental monasteries, most of which

were extensively renovated from the fifteenth century onward

and remained in continuous use up to the French

Revolution. No claim for completeness is made. The observations

set forth are based on a survey of the remains of

not more than twenty-one Cluniac and autonomous

Benedictine monasteries of the eleventh and twelfth

centuries. The Clunaic abbeys are Lewes, Castle Acre,

Thetford, and Much Wenlock; the autonomous abbeys:

Battle, Bardney, Christchurch, Canterbury, Gloucester,

St. Albans, Ely, St. Augustine's Canterbury, Westminster,

Rochester, Durham, Bury St. Edmunds, Peterborough,

Norwich, Winchester, Reading, Worcester, and Finchale.[93]

This sampling, admittedly, is small when viewed against

the total of Benedictine monasteries flourishing at this time.

Yet their comparison conveys a surprisingly uniform picture.

They disclose that the layout adopted at Cluny was

transmitted to the English houses and became traditional.

* * * * * * * * * *

VI.3.2

TRADITION

Many autonomous Benedictine monasteries adopted the

customs of Cluny. Christchurch, Canterbury, for instance,

was built by Lanfranc, who was previously prior of the

Abbey of Bec in Normandy. The customs of Bec are true

to the earlier customs of Cluny which William of Volpiano

brought to Fécamp and other northern monasteries at the

beginning of the eleventh century. The monastic constitutions

which Lanfranc later wrote are similar to the customs

composed under Odilo between 1030 and 1048.[94]

There was

continual interaction between Cluny and the autonomous

English houses and in many cases Cluny must have transmitted

the reform ideas promulgated at Aachen.

Earlier ties, however, also connect the English monasteries

with the synods of Aachen. The monastic revival

begun by Dunstan in the second half of the tenth century

was based on the continental monastic tradition of Benedict

of Aniane.[95]

While in exile Dunstan took refuge in the monastery

of Blandium at Ghent in 954. Around 970 a synod

under Dunstan's guidance was called at Winchester to

establish a common way of life for English monasteries

under the patronage of King Edgar. The procedure and

provisions of the meeting consciously imitated those of the

synod at Aachen, directed by Benedict of Aniane in 817

under the auspices of Louis the Pious. In the presence of

monks from Fleury and Ghent the Regularis Concordia, a

code based on the Ordo Qualiter and the Rule for Canons

and Capitula of Aachen, was drawn up.[96]

About forty monasteries

were founded under this revival between 957 and

the Conquest, but no architectural remains seem to indicate

the arrangement of the conventual buildings before the last

phase of this revival during the reign of Edward the Confessor.

At this time both the style of Norman architecture

(exemplified by Westminster Abbey, consecrated in 1065)

as well as the typical institutions of Norman monasticism,

that clearly characterize post-Conquest England, were

already established.[97]

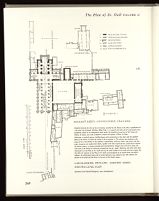

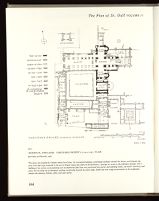

In the Post-Conquest English Benedictine monasteries

of the eleventh and twelfth century, the east range of the

cloister contains the dormitory; the south range, the refectory;

and the west range, the cellar, as on the Plan of St.

Gall and at Cluny II.

These relationships have become traditional and binding.

Whenever the site permitted in the few examples that

remain the peripheral houses and workshops were arranged

as they were on the Plan of St. Gall. The entrance to the

monastery is usually to the west of church and cloister. The

mill and bake house are adjacent to the kitchen, as on the

plan of the waterworks of Christchurch, Canterbury (Kent),

shown above in figure 52. The infirmary, its chapel and

cemetery are to the east of the cloister, as can be seen at

Christchurch and at Bardney Abbey, Lincolnshire, (fig.

516).

In some particulars the English plans reflect the arrangement

on the Plan of St. Gall even more closely than Cluny

II. In all of these monasteries the east range of the cloister

is aligned with the southern transept-arm and the cloister

forms a regular square. Whenever the location of the

twelfth century kitchen is known, as on the Canterbury

plan (fig. 52), it is isolated from the refectory and connected

with the south range by passageways, as it was on the

Plan of St. Gall; while at Cluny II it may have been part

of that range. As at St. Gall, there is only one kitchen;

Cluny had two.

Other aspects seem closer to the Plan of St. Gall, but

they are not well enough established to allow generalization.

In some English monasteries such as Thetford (fig. 517),

part of the undercroft of the dormitory may still have served

as the warming room, but it is considerably reduced

in area and pushed to the southern part of the range.

There is some indication that in later English monasteries

night stairs connected the dormitory with the southern

transept arm of the church, as it did on the Plan of St. Gall.

In Cluny (fig. 515) such a connection probably would not

have existed if the east range, as Conant assumes, was

severed from the transept. In Cistercian planning the night

stairs reappear in the place where they were indicated on

the Plan of St. Gall. Since the elements that Cistercian

planning have in common with the Plan of St. Gall could

only have been transmitted by later Benedictine monasteries,

they must have been more common in Benedictine

planning than present remains indicate.[98]

Our survey of English monastery plans also reveals that

the dimensions of the cloister square comply with the standards

set by the Plan of St. Gall and with the stipulation

made by Hildemar of Corbie (ca. 845) that a cloister yard

should never be less than 100 feet square.[99]

In the Benedictine

and Cluniac English monasteries the cloister yard, as a

rule, is not smaller than this, though it is sometimes larger.[100]

These basic similarities between the English monasteries

and the Plan of St. Gall remain constant wherever the

natural conditions of the site permit. When exceptions occur

they can be explained either by the topography or by restrictions

imposed by the architectural surroundings.[101]

In

England such irregularities are more common in Benedictine

than in Cistercian monasteries because the Benedictines

rarely had a virgin site on which to build and were

often settled near cities, while the Cistercians chose isolated

areas, a fact which may be primarily responsible for

what, in contrast to Cistercian conformism, appears to be

a lack of uniformity in Benedictine planning.

VI.3.3

INNOVATIONS

CHAPTER HOUSE

Certain innovations made at Cluny became an integral part

of the later Benedictine tradition and remained in permanent

departure from the solution set forth on the Plan of

St. Gall. The most notable of these is the inclusion in the

east range of a separate chapter house.[102]

Once conceived, the

separate chapter house could not be abandoned because of

its functional advantages. To place the chapter house at the

northern end of the east range, however, brought with it

certain complications. As long as it remained confined to

the ground floor, the dormitory overhead could still be

connected directly with the transept by means of night

stairs. But if the space of the chapter house extended upwards

through the entire height of the east range, arrangements

had to be made to connect the dormitory with the

church by special passageways; or the night stairs had to be

abandoned altogether.[103]

INNER PARLOR

A second permanent innovation adopted by the Benedictine

monasteries was the inclusion of an inner parlor in

the east range, directly adjacent to the chapter house. Although

this inner parlor is referred to by name in several

Benedictine and Cluniac customs, its function is not stated.[104]

An auditorium is first mentioned in the Farfa description

of 1043.[105]

Later in the eleventh century it is mentioned in

the tours of the claustral prior at Cluny and Hirsau.

Bernard's account of the claustral prior's tour at Cluny in

his Ordo Cluniacensis refers to a parlatorium in the same

context that the otherwise similar tour in the Consuetudines

of Hirsau refers to the auditorium.[106]

This designates the

inner parlor in the east range as a place for talking and

listening.

Twelfth-century customs outside the Benedictine order

further explain the exact use of the auditorium. Cistercian

customs describe the auditorium as the place where monastic

officials could converse privately with one or two monks,

where the prior made work assignments, and handed out

tools for the day's work after the chapter meeting, and

where the master of the novices could instruct new novices.[107]

The Liber Ordinis S. Victoris Parisiensis further specifies

that in this order of canons the auditorium or locutorium,

as it is called in this text, was particularly used for briefly

talking about any business that could neither be signified

(probably referring to sign language) nor put off until the

time of the locutio, but the Liber emphasizes that no one

could talk there without permission from a high member of

the order.[108]

It explicitly states that no stranger may be led

into this "regular locutorium" and also mentions rules for

the "other locutorium," thus distinguishing between the

locutorium or auditorium in the east range and the auditorium

in the west range, which, as on the Plan of St. Gall, served

as reception room for visitors. The auditorium in the east

range of the twelfth-century cloister is thus defined as a

place where claustral silence could be broken to discuss

necessary business. This had probably been its role since

its beginning.

Although silence was at all times considered a basic

monastic virtue it had not always been as severely enforced

as it was by the Cluniacs, the later autonomous Benedictines,

and the Cistercians. St. Benedict, in dealing with this

problem, referred to it as taciturnitas rather than silentium.[109]

He designated three regular periods of absolute silence; but

for the rest of the time only excessive loquacity was forbidden.

The same relative freedom of speech, except at

certain regulated periods, is evident in the monastic customs

of the eighth and ninth centuries. The rule of ordinary

silence is in fact so relaxed that a consuetudinary from

Corbie of around 826 permits conversation during the midday

rest in the summer, provided that it does not bother

those who sit and read in bed; should there be any need for

sustained talk the monks must simply go outside and conduct

their business there. In the same text they are instructed

not to yell from a distance because of the noise.[110]

Under

relaxed conditions like these there was no need for a special

room in which the ordinary claustral silence could be

broken. No such area, consequently, is set aside on the Plan

of St. Gall.

Joseph Semmler has pointed out that it was not until the

tenth century that the monks began to practice strict silence

during the days of the great religious festivals. This trend

toward increased enforcement of silence is true of the reformed

German monasteries, the English monasteries that

adopted the reform of Dunstan, and it is also true in particular

for Cluny.[111]

In the eleventh century men like Peter Damian (9881072),

inspired by the same ideals of reform as Cluny,

wrote impassioned letters against unnecessary talking and

forcefully recommended greater silence.[112]

At Cluny, as the

number and length of the breaks in silence were progressively

reduced, as absolute silence was required even in the

workshops, a sign language was developed to maintain the

necessary communication.[113]

The auditorium in the east

range, first mentioned in the Farfa description, provided an

area for talking aloud and may well owe its existence to the

pressure of increasing claustral silence. Like the sign language

it might also have originated at Cluny. Just as the

sign language was adopted by nearly all the later medieval

monasteries, the auditorium in the east range became an

integral part of all later Benedictine and Cistercian planning.[114]

NOVITIATE

Another innovation made at Cluny that seems to have been

permanently adopted in later monastic planning was the

transfer of the novitiate to a location more closely related to

the quarters of the regular monks. The Constitutions of

Lanfranc reflect a growing tendency to integrate the novices

with the regular monks in the eleventh century English

Benedictine monasteries: "The novice shall sleep in the

cell of the novices, or, if the monastery have no such special

cell, in the dormitory.[115]

"He shall be taken into the church

and a place assigned to him. From the church he shall be

taken to the dormitory and the place shown him where he

is to rest, and he shall be taken beyond the dormitory, and

the cells shown him to which he is to repair when nature's

ways demand it . . . on that day the novice shall follow, and

a seat in the refectory shall be assigned."[116]

These passages

by Lanfranc suggest that in the late eleventh and twelfth

century there was not always a separate building for the

novices and that they often shared the buildings of the

regular monks. In the English plans there is no indication

of a special court of building set aside for novices.

The novices were probably often integrated with the

monks for economic reasons and perhaps also because there

were not as many oblati in the eleventh and twelfth centuries

as there were in the ninth century. According to

David Knowles, despite Lanfranc's attempts to perpetuate

the age-old institution of child oblation, it was everywhere

on the decline fifty years after his death.[117]

ABBOT'S HOUSE

As at Cluny, so in the autonomous English Benedictine

houses: a change in customs was responsible for the disappearance

of a separate house for the abbot. But this issue

remained controversial, as it had been in the days of St.

Benedict of Aniane.[118]

Like the Customs of Udalric, the

Constitutions of Lanfranc[119]

reveal that the abbot slept in the

dormitory: "In the early morning no one shall dare to make

a sound as long as (the abbot) is in bed asleep."[120]

Yet by

1150 all but a very few abbots in England had removed to

quarters of their own.

[121]

Brakspear, in his survey of English

abbots' houses, discloses that by the thirteenth century the

abbot, as on the Plan of St. Gall, is once more provided

with a separate building, usually connected to the outer

parlor with guest houses next to it. This is the case at

Battle and Castle Acre (fig. 518).

[122]

WARMING ROOM

Other changes made at Cluny, like the moving of the

warming room from the east range to the south range, may

have also occurred in some English Cluniac and autonomous

Benedictine houses, but in other cases the warming room

may have remained in the east range as on the Plan of St.

Gall, although it was reduced in size. In the Cluniac priory

of Thetford, indications of a fireplace suggest that the

warming room may have been located in the southern half

of the east range.[123]

But in many other Benedictine monasteries

an area in the east range is designated as the warming

room solely by analogy with a passage in the Rites of Durham

of 1593 indicating that the warming room was located

in the east range at that time.[124]

Although the sixteenth-century

location might reflect an earlier arrangement, this

source cannot be used as compelling proof that the warming

room occupied this position in the twelfth century.

Bernard's description of the course followed by the

claustral prior in the Ordo Cluniacensis of 1086 indicates

that the warming room in the eastern extremity of the south

range at Cluny also served as a passage to the novitiate

which was located to the south of the cloister.[125]

In most

English plans this area between the east range and the

refectory in the south range also forms a passage between

the cloister yard and the area to the south. In cases like

Finchale, where the area is only 5 feet wide, it could have

served only as a passage, but in others, such as Lewes or

Castle Acre, where it is 25 feet wide, it could have served

the additional function of warming room as did the 25-foot

space in the same position at Cluny.[126]

If this area at Castle

Acre had been intended solely as a passage, it probably

would have been made no more than 10 feet wide, as the

passage in the east range was. It can, however, only be

concluded that insufficient evidence makes it impossible to

determine with certainty the location of the warming room

in eleventh- and twelfth-century English monasteries. It is

possible that the location varied from place to place.

Whether the warming room was in the south range as at

Cluny (fig. 515) or in the southern half of the east range, as

it may have been at Thetford (fig. 517), its area is greatly

reduced in size from the area of the warming room which

covered the entire ground floor of the east range on the

Plan of St. Gall. At Thetford it would have occupied an

area of no more than three bays. A comparison of the relative

areas of the warming rooms of St. Gall (7), Cluny (1.3),

Thetford (2.5), and Castle Acre (1.2) shows that St. Gall

is two and one-half to five times larger.[127]

Mettler suggested that the reduction in size met the new

demands of asceticism of the Cluniac reform.[128]

Although

the smaller area could have been due to a change in ideals,

it may also simply have resulted from changes in other

parts of the east range. In the ninth century, according to

Adalhard, the warming room served as a place where the

monks could meet for conversation at certain hours.[129]

Passages

in Ekkehardus IV, as has been previously pointed

out, indicate that in the early eleventh century the warming

room, at least at St. Gall, served also as a chapter house.[130]

After separate rooms (the new chapter house and an inner

auditorium) had been provided for these functions, it may

have seemed that a large room was no longer necessary.

A change in the heating methods between the ninth and

the eleventh century also may have influenced the reduction

in size. Harold Brakspear suggested that the scarcity of

fireplaces in English monasteries is due to the fact "that in

Benedictine houses there was no fireplace in the commonhouse,

but that in cold weather it was lighted on the floor

or in a brazier and the smoke was allowed to find its way

out of the windows, as was usual in domestic halls."[131]

The

hypocaust system seen on the Plan of St. Gall could heat a

large area; an open fire on the floor could not.[132]

With the

method that Brakspear suggests a smaller room could be

more easily heated. This method of heating might also

explain why in some cases, as at Cluny II, the warming

room was moved from the east to the south range. There

was usually no upper story in the southern range so nothing

prevented the smoke from escaping directly through an

opening or louver in the roof. Such a louver would not have

been possible if the warming room were beneath the dormitory.

Moving the warming room to the south range may

have also reduced the chance of the dormitory catching fire.

At any rate, the arrangement set forth on the Plan of St.

Gall was altered, and the new position of the warming

room at Cluny and in some English monasteries was also

adopted in Cistercian monasteries.