V.1.2

THE NORTHERN SCHOOL

All the theories heretofore reviewed have in common the

fact that they attempted to explain the guest and service

structures of the Plan of St. Gall in the light of house types

presumed to have existed in Etruscan, Roman, and Gallo-Roman

times. The most ardent exponent of this school,

Franz Oelmann, expressed himself in no uncertain terms

when he summarized his views with the phrase, "The Plan

of St. Gall, then, must be derived in its entirety from the

Classical tradition, i.e., from Roman architecture, and of

Northern influences . . . there can be no question whatsoever."[35]

The uncompromising fervor of this assertion is

clear evidence that at the time these lines were written, the

issue had already entered a highly controversial phase.

And indeed, as early as the last two decades of the nineteenth

century, the views of the classicists had begun to be

progressively challenged by the speculation of an opposing

school that proposed to reconstruct the guest and service

structures of the Plan of St. Gall in the light of northern

rather than classical building traditions. The seeds of this

theory may actually be discovered in the writings of some

of the exponents of the classical school. When Rahn, in

1876, interpreted the testu[do] squares as symbols for a

lantern-surmounted opening in the roof above the hearth,

he breached the thinking of the classicists, since this was a

solution suggested by analogy with northern rather than

with southern building types. Yet, apart from this "intrusive"

detail, Rahn's reconstruction was essentially a product

of the classical school. A square attack on the theories

of the latter, however, was launched in 1882 by Rudolf

Henning.

RUDOLF HENNING, 1882

In a study entitled "Das Deutsche Haus in seiner historischen

Entwickelung,"[36]

Rudolf Henning stressed the resemblance

of the plan of the St. Gall house to certain

house types still used in Upper Germany and in Switzerland,

in territories once occupied by Frankish, Alamannic,

and Bajuvarian tribes. In dwellings of this type (fig. 275)

such as is exemplified by a house from the Engadin in

Switzerland, the hearth is, as a rule, located in a common

center room (Eren) from which access is gained to all the

subsidiary outer rooms. It is surmounted by a wooden

smoke flue of pyramidal shape which projects beyond the

roof like a chimney and can be closed and opened by an

adjustable lid. A similar arrangement is found even today

in old farmhouses of Denmark (fig. 276). Henning did not

propose that the St. Gall house was equipped with such a

smoke flue. He believed, on the contrary, that it had an

open hearth and, in the roof above the hearth, a lantern-surmounted

opening that served as a smoke outlet and as a

light source. He imagined the St. Gall house to have been a

spacious, steep-roofed structure with inner wall partitions

that did not obstruct the view of its enclosing walls and

rafters. He felt supported in this assumption by a passage

in the Lex Alamannorum which makes the paternal right

of inheritance dependent on the ability of the newborn

child to encompass the roof and the four corners of the

house as he opens his eyes.[37]

The existence of a house of

this description, Henning felt, must be postulated as the

medieval prototype form of the modern Swiss and Upper

German farmhouses with central hearth and central accessibility

of the subsidiary outer rooms; and, in the houses of

the Plan of St. Gall, he believed to have discovered the

first pictorial evidence of this prototype form. The development

that leads from this archetype to its modern derivative,

Henning assumed, was characterized by the gradual

substitution of a stone-built stove with smoke flue for the

originally open fireplace, and by the removal of the light

source from the ridge of the roof to the walls, which became

necessary when the opening in the ridge was obstructed by

the installation of a central smoke stack.

The beginnings of this displacement of the open fireplace

by stone-built stoves, Henning suggested, may already be

observed in some of the more distinguished structures of

the Plan of St. Gall, such as the House for Distinguished

Guests, where the common central fireplace is already

supplemented by stone-built corner fireplaces.

KARL GUSTAV STEPHANI, 1902-1903, AND

CHRISTIAN RANCK, 1907

Henning refrained from embodying his ideas about the

St. Gall house in a visual form, and in the fifty years that

followed, this theory found neither support nor acceptance.

The views expressed in Karl Gustav Stephani's encyclopedic

work on the early German dwelling and its furnishings,[38]

as well as those in Christian Ranck's percursory but

widely read cultural history of the German farmhouse,[39]

are literal repetitions of Julius von Schlosser and show that

the work of even those who specialized in the history of the

German house was still entirely under the spell of the

thinking of the classicist. But in the third decade of this

century, the method that Henning had initiated, namely,

that of attempting to reconstruct the St. Gall house in the

light of its modern derivatives rather than of its historical

prototypes, found a sudden revival in a number of visual

reconstructions that marked a complete departure from

the thinking of the classical school. These reconstructions

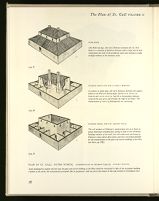

(figs. 277-281) came from the hands of men who were not

primarily historians but professional architects, and they

were the product of intuitive speculation rather than of

documentative historical study. The first of these was made

by H. Fiechter-Zollikofer in 1936.

H. FIECHTER-ZOLLIKOFER, 1936

Mr. Fiechter-Zollikofer, a Swiss engineer, wrote an article

entitled "Etwas vom St. Galler Klosterplan aus der Zeit

um 820," which was published in the Schweizerische Technische

Zeitschrift,[40]

a journal not normally read by the

architectural historian of the Middle Ages. In this article

Fiechter-Zollikofer reproduced not only an over-all reconstruction

of the entire monastery shown on the Plan of St.

Gall, in bird's-eye view (fig. 277), but also a separate reconstruction

of the exterior of the Outer School (fig. 278), the

exterior of the Abbot's House (fig. 254), as well as a number

of perspectives and cuts of the church and the claustral

structures.

Fiechter-Zollikofer was convinced that the traditional

concept of the St. Gall house as a dwelling that received

its light in the Italian manner through windows in its

clerestory walls was incompatible with the climatical conditions

prevailing in transalpine Europe, and that a solution

infinitely better adapted to the rain and snowswept foothills

of the Alps could be found if the St. Gall house were

reconstructed in the light of certain rural timber dwellings

still used in many districts of Switzerland.

Accordingly, he reconstructs the St. Gall house as a

low-roofed, low-walled gable house of logs with corner-timbered

protruding beams (fig. 278). The center room

of this house receives its light through a large tapering

shaft mounted upon the ridge of the roof which could be

opened and closed through an adjustable lid (fig. 279); the

outer rooms were lighted through windows in the peripheral

log walls. Fiechter-Zollikofer's reconstruction is the first

attempt to interpret the guest and service structures of

the Plan of St. Gall in the light of an actually existing

vernacular house type. It is a handsome reconstruction,

but the prototype after which it is modeled, the Alpine

log house, is too closely associated with local conditions to

have been adopted in a master plan that was drawn up for

the whole of the Frankish empire. Log construction depends

on abundant stands of fir trees, such as are available in the

Alps, the Black Forest, and the mountain ranges of Scandinavia;

but in the lowlands this material was lacking.

Moreover, Fiechter-Zollikofer did not enter into any

detailed analysis of the internal layout of these houses. He

did not support his reconstructions with any specific parallels

with comparable structures still in existence, or attempt

to trace this house type to its historical past.

OTTO VÖLCKERS, 1937

Fiechter-Zollikofer's article had barely been published when

the German architect, Otto Völckers, touched upon the

problem of the St. Gall house in a small, handsomely

illustrated book in which he reviewed the history of the

European house from the Stone Age to the present.[41]

Völckers exemplified his views with a reconstruction of

St. Gall's House for Distinguished Guests (fig. 280). This

he imagines to have been a steep-roofed structure, hipped-over

on the narrow ends of the building. The walls are low

and masonry-built with windows giving light to the external

rooms. The center room is lighted by an opening in the

ridge above the hearth site, which also serves as a smoke

outlet and is surmounted by a small protective roof that

shields the opening against any downpour. The heating

units in the bedrooms of the distinguished guests are

interpreted as corner fireplaces with masonry stacks protruding

through the roof above them. Völckers did not discuss

the structure in any further detail, but judging from an

interior view of the dining room (fig. 281) which he published

in a subsequent book,

[42]

he appears to think of the

inner wall partitions as likewise being built as solid masonry

walls.

KARL GRUBER, 1937

The same year that Völckers published his pictorial review

of the history of the German house, and probably independent

of both Völckers' and Fiechter-Zollikofer's proposal,

Karl Gruber published still another reconstruction of the

Plan, in bird's-eye view, in a superbly illustrated book,

entitled Die Gestalt der deutschen Stadt (fig. 282).[43]

Like

Fiechter-Zollikofer, Gruber reconstructs the St. Gall house

as a house with low pitched roof and straight gable walls on

the narrow sides. It receives its light from windows in the

supporting walls and emits the smoke of its hearth through

a louver in the ridge of the roof. The latter, as in Völckers'

reconstruction, is rendered as a miniature roof, raised above

the level of the main roof to protect the opening over the

hearth site. Gruber is not specific about the material used

in the construction of his houses. The uniform mode of the

rendering of the walls suggests that he thought of them as

being built in masonry.