The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. | V. 1 |

| V.1.1.. |

| V.1.2. |

| V.1.3. |

| V.1.4. |

| V. 2. |

| V.2.1. |

| 10. |

| 10. |

| V.2.2. |

| V. 3. |

| V.3.1. |

| V.3.2. |

| V.3.3. |

| V. 4. |

| V.4.1. |

| V.4.2. |

| V.4.3. |

| V. 5. |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

| V. 6. |

| V.6.1. |

| V.6.2. |

| V.6.3. |

| V.6.4. |

| V. 7. |

| V.7.1. |

| V.7.2. |

| V.7.3. |

| V.7.4. |

| V.7.5. |

| V.7.6. |

| V. 8. |

| V.8.1. |

| V.8.2. |

| V.8.3. |

| V.8.4. |

| V.8.5. |

| V.8.6. |

| V.8.7. |

| V.8.8. |

| V. 9. |

| V.9.1. |

| V.9.2. |

| V.9.3. |

| V. 10. |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. |

| V. 11. |

| V.11.1. |

| V.11.2. |

| V.11.3. |

| V. 12. |

| V.12.1. |

| V.12.2. |

| V.12.3. |

| V. 13. |

| V.13.1. |

| V.13.2. |

| V. 14. |

| V.14.1. |

| V.14.2. |

| V. 15. |

| V.15.1. |

| V.15.2. |

| V.15.3. |

| V.15.4. |

| V. 16. |

| V.16.1. |

| V.16.2. |

| V.16.3. |

| V.16.4. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| V.18.1. |

| V.18.2. |

| V.18.3. |

| V.18.4. |

| V.18.5. |

| VI. |

| VI. 1. |

| VI.I.I. |

| VI.1.2. |

| VI.1.3. |

| VI.1.4. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI.2.1. |

| VI.2.2. |

| VI.2.3. |

| VI.2.4. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI.3.1. |

| VI.3.2. |

| VI.3.3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI.4.1. |

| VI.4.2. |

| VI.4.3. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V. 1

PREVIOUS INTERPRETATIONS

V.1.1.

THE CLASSICAL SCHOOL

FERDINAND KELLER, 1844

The first to speculate about the design of the guest and

service buildings of the Plan of St. Gall was Ferdinand

Keller. In his "facsimile" edition of the Plan, published

in 1844, Keller described them as structures "of oriental

style in which the living quarters are arranged around an

open central court toward which the roof slopes down from

all four sides of the building."[1]

Keller explained the squares

—which are designated by the term testu[2]

in the explanatory

titles—as "courtyard houses" or "garden huts." He

did not illustrate his views with graphic reconstructions,

but the kind of structures he had in mind must have

resembled the houses sketched in figure 264 A-C. Keller's

interpretation is perplexing because it contradicts the

explanatory titles of the Plan itself, which he had so carefully

transcribed, translated, and annotated. In seven out

of the nine times this house-type appears on the Plan of

St. Gall, the area that Keller interprets as an open inner

court is explicitly designated as the "common" or "principal"

room of the house by inscriptions such as domus

communis (House of the Fowlkeeper), domus ipsa (House for

Sheep and Shepherds), domus familiae (House for Visiting

Servants), domus pauperum et peregrinorum (House for

Pilgrims and Paupers). Keller, however, was not truly

consistent in this matter; for in the case of the House for

Distinguished Guests, where the function of the center

area as an indoor space is visually elaborated by the insertion

of pieces of indoor furniture such as tables (mensae),

benches, and a fireplace (locus foci), he interprets the center

space of the house correctly—and in full accord with its

identifying inscription as "dining room" (domus ad prandendum).

The incompatibility of this interpretation with

that of the other guest and service structures as open courtyard

houses does not appear to have raised any doubts in

his mind of the validity of the latter.

Keller, 1844, 15: "Fast alle grösseren Häuser sind im orientalischen

Stile erbaut, indem sie in ihrer Mitte einen Hof einschliessen, nach

welchem sich von allen vier Seiten die Dächer absenken." The idea is

elaborated further in the chapters that deal with the individual structures.

He remarks, with regard to the Outer School (p. 25): "Sie ist ein weitläuftiges

Gebäude mit einem Hof in der Mitte, welcher durch eine

Mauer in zwei Hälften getheilt ist. In jeder Abtheilung bemerkt man

ein Viereck mit der Bezeichnung testudo, worunter zwei Gartenhäuschen,

oder die ausser allen Verhältnis klein vorgestellten gemeinschaftlichen

Schulzimmer zu verstehen sind"; with regard to the Paupers' Hospice

(p. 27): "Die vier Flügel dieses Gebäudes schliessen einen Hofraum ein

dessen Mitte von einem kleinen Hause, testudo, besetzt ist"; with regard

to the Great Collective Workshop (p. 30): "Es schliesst zwei viereckige

Höfe ein, in deren Mitte zwei kleine, von den Meistern oder Aufsehern

bewohnte Häuschen, domus et officina camerarii, stehen"; with regard to

the six agricultural buildings for livestock and visiting servants (p. 33):

"Jedes dieser sechs Gebäude schliesst einen Hof ein, in welchem ein

kleines, vielleicht von den Aufseher bewohntes oder zum Aufenthalte

der Knechte bestimmtes Häuschen steht."

In the entire literature on the Plan of St. Gall the term testu (literally

"skull" or "lid") has been interpreted, without exception, as standing

for testudo (literally "tortoise," by extension "protective cover,"

"roof" or "vault"). Later on in this study, I give the reasons for which

I think this interpretation is in error (see below, p. 117). In order to keep

the reader apprised of the fact that testudo is improper exegesis, I am

putting the terminal syllable do into brackets (testu[do]), whenever I refer

to the views of other students of the Plan who interpret the term in its

traditional meaning.

ALBERT LENOIR, 1852

We do not know what specific prototypes Keller had in

mind when he explained the St. Gall house as the descendant

of an oriental courtyard house, but once this idea was

suggested it was inevitable that the design of the St. Gall

house should also be connected with that of the Roman

atrium house. This idea was pursued in 1852 by Albert

Lenoir.[3]

Lenoir derived the St. Gall house from a subvariety

of the Roman atrium house that Vitruvius had

called "Tuscan" (tuscanum)—a house with an open inner

court which was partially roofed over (fig. 265), but which

retained in its center a large rectangular "rainhole"

(compluvium) and on the ground below it, the classical

Roman rain catch basin (impluvium).

To the difficulties of Keller's reconstruction, Lenoir

thus added a further one, since testu[do] can be translated

as neither "rainhole" nor "catch basin." Whatever the

specific implications of this term may be, its basic meaning,

"tortoise" or "turtle shell," points in the opposite direction,

namely, to that of a protective shield or cover.[4]

Cf. above p. 2, and below pp. 117ff. Lenoir himself appears to have

entertained some doubt with regard to the suitability of such a reconstruction

for a house in a northern climate when he states (p. 26): "Si,

en raison de la température froide de nos contrées, on suppose cette

ouverture close par des vitres, sa disposition sur l'atrium toscan n'est pas

moins celle de l'antiquité. Dans les bâtiments ruraux on retrouve aussi

ce carré figuré au centre; là, plus qu'ailleurs, il peut figurer un impluvium,

bassin recevant les pluviales par l'ouverture du toit ou compluvium."

J. R. RAHN, 1876

Probably aware of these inconsistencies in Keller's and

Lenoir's interpretations, the Swiss art historian J. R. Rahn

presented a new solution in 1876, which was incorporated

into a graphical reconstruction of the entire settlement in

a bird's-eye view drawn up for him by Georg Lasius

(fig. 266).[5]

Without explicitly refuting or even discussing

Keller's and Lenoir's views, Rahn reconstructed the St.

Gall house as a masonry structure of basilican type with a

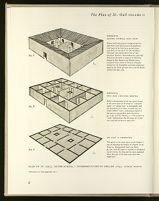

PLAN OF ST. GALL. OUTER SCHOOL.[6] INTERPRETATION OF KELLER (1844). AUTHORS' DRAWING

264.C PERSPECTIVE

SHOWING INTERNAL OPEN COURT

Houses with living quarters ranged around an

open inner court were in use in the Euphrates

river basin in the Isin Larsin period (20241763

B.C.) in the city of Ur (H. Frankfort,

The Art and Architecture of the

Ancient Orient, Harmondsworth, 1958, 66).

They form the point of origin of an illustrious

lineage of Near Eastern and Mediterranean

courtyard houses which in Classical Antiquity

evolved into the beautifully conceived symmetrical

layout of the Greek peristyle house and the Roman

atrium house (fig. 265).

264.B PERSPECTIVE

WITH ROOF STRUCTURE REMOVED

Keller's interpretation of the two squares drawn

in the center space of this house as "courtyard

houses" or "garden huts" is incompatible with

the annotation of the Plan, on which they are

clearly labeled "testu", indicating a feature of

the roof on a ground floor plan. See below,

pp. 117ff, and III, Glossary, s.v. The presence of

"testu" demonstrates that the house was roofed

over, and did not have an open court.

264.A THE PLAN IN PERSPECTIVE

The squares in the center space are the designer's

way of indicating the location of a hearth. In the

House for Distinguished Guests (see below,

pp. 146, 160) this square is explicitly so designated

(LOCUS FOCI). For this and the reason explained

above, this part of the house must have been

roofed over.

rooms and received its light through clerestory windows.

The squares that are inscribed in the Plan alternately as

locus foci and testu[do] Rahn interprets as open fireplaces

surmounted on the level of the main roof by a lantern with

openings for the escape of smoke. This solution was suggested

to him by similar architectural contraptions "still

nowadays in use in certain rural houses of northern

Germany and also occasionally found in England."[7] Rahn's

reconstruction has subsequently found the widest circulation

by being reproduced in Cabrol-Leclercq's Dictionnaire

d'archéologie chrétienne.[8] It also formed the basis for a

masterful three-dimensional model, executed in 1877 by

Julius Lehmann, which found a permanent home in the

Historisches Museum of the city of St. Gall (fig. 267).[9]

The advantages of Rahn's reconstruction over those of

Keller and Lenoir are obvious at first sight. It establishes

correctly, and in accordance with the legends of the Plan,

the large rectangular center space of the house as a covered

room. Second, it associates the term testu[do] with a

device that is compatible with its etymology (protective

shield, or cover). Third, it offers a constructive solution to

the interchangeability of the terms testu[do] and locus foci,

since "hearth" and "lantern," if arranged in the manner

Rahn suggested, would merely be two complementary

aspects of the same device—namely, an open fire with a

smoke hole in the roof surmounted by a lantern.

The statement is not further substantiated. Rahn, however, was not

the first to suggest such a solution. It was considered as early as 1848 by

Robert Willis (1848). Willis' interpretation of the St. Gall house vacillates

between that of Keller, whom he follows closely in his general

description of the Plan, and suggestions that could be called anticipations

of Rahn's and Lenoir's views, as may be gathered from the following

quotations: in connection with the House for Distinguished Guests

(p. 90): "This central room either rose above the roofs of the others,

so as to allow for small open windows like clerestory windows, or else the

central room was so roofed over as to leave a small square opening in the

middle, which admitted light and allowed the smoke of the fire to escape.

In warm southerly climates, as at Pompeii, the opening had a cistern

below to receive rain. But in the north, if a fire-place was below it, the

central opening must have been covered with a sort of turret or lantern,

with open sides, to prevent the rain from pouring down upon the fire";

with regard to the other buildings (p. 91): "I am inclined to think that

. . . the central square in most of the examples . . . represents the central

opening of a roof, which roof may either slope outwards or inwards, as

the case may be"; with regard to the farm buildings (p. 91): "In the

great farm buildings at the south-west part of the establishment the

small central square may indicate that the central space has an overhanging

shed carried round it, leaving the opening in the middle; or if

this appears improbable, we must suppose in this case that it means a pond

for water, or, as Keller seems to think, a little cabin or sentry-box,

which I confess does not appear very likely."

On the history of the construction of this model see Edelmann, in

Studien, 1962, 291-95. The model in turn served as prototype for a

painting made by B. Steiner in 1903 for use in school instruction, which

shows the monastery from the south east. This painting has never been

published, so far as I have been able to determine. It places the settlement

shown on the Plan of St. Gall into the topographic relief of the

site on which the monastery of the Abbey of St. Gall rose. Since it adds

nothing to the concept of the buildings established by Rahn and Lasius,

I pass over it.

JULIUS VON SCHLOSSER, 1889

Rahn's reconstruction of the St. Gall house as a basilican

masonry structure with a lantern-surmounted central

hearth had been a purely theoretical venture. He could not

prove—and did not even attempt to prove—that houses of

this description actually existed.

Misconceptions about the "displuviate" and

"testudinate" Roman courtyard house

Julius von Schlosser[10]

tried to overcome this weakness by

demonstrating that Rahn's St. Gall house was historically

the descendant of a once widespread Roman house type to

which the ancients referred with the terms "displuviate"

(displuviatum) and "testudinate" (testudinatum). Schlosser's

theory, unfortunately, was based on two erroneous assumptions

that were current in his day, which imparted to the

discussion of the design of the guest and service structures

of the Plan of St. Gall an element of further confusion.

The first of these misconceptions pertained to the precise

meaning of the terms "displuviate" and "testudinate";

the second concerned the origins and structural evolution

of the Roman atrium house.

To begin with the former: what Vitruvius and Varro

designated by the terms "displuviate" and "testudinate"

can under no circumstances be interpreted as structures

of basilican design. They were atrium houses in the full

constructional sense of the term, i.e., houses in which the

living quarters were ranged around an originally open

center space. The terms "Tuscan", "Corinthian", as well

as "tetrastyle", "displuviate", and "testudinate" (tuscanicum,

corinthium, tetrastylon, displuviatum, and testudinatum)

merely referred to the different degree or manner in which

these inner courtyards were roofed over.[11]

In the Tuscan

atrium house, for instance, the courtyard roof sloped down

toward the center (fig. 265); in the displuviate house it

sloped upward. But in both cases the courtyard roof

encompassed in its center a rainhole (compluvium) that had

under it not a hearth, but a catch basin (impluvium).

Schlosser did not realize that in connecting the St. Gall

house with the displuviate Roman atrium house, he had

actually retrogressed to Lenoir's views (fig. 265), whose

weakness Rahn's reconstruction (fig. 266) had already

successfully overcome.

The same applied to Schlosser's attempt to connect the

St. Gall house with the courtyard house referred to by

Vitruvius and Varro by the term "testudinate." It is an

atrium house like all the others, as must be inferred not

only from the language of the opening sentence with which

ROMAN ATRIUM HOUSE WITH RAIN

CATCH-BASIN

265.B PERSPECTIVE redrawn after Kähler, 1960, suppl. 53, fig. 31

265.C

265.A PLAN, based on Luckenbach, Kunst and Geschichte, I: Altertum,

Munich, 1910, 94

SECTION, authors' interpretation

The plot, 60 feet wide, is 1/2 ACTUS (120 feet)

See remarks on Roman land surveyor's measure, page III. 140

In the form here shown, the Roman atrium house has its open inner

court partially covered by an inward-sloping roof with its center

open to the rain (COMPLUVIUM); beneath this opening in the center

of the court is a collecting basin (IMPLUVIUM). The dining room

(TABLINUM) lies to the rear of the house and opens onto the garden

(HORTUS). The kitchen stove might have been located in any of the

cubicles adjacent to it.

generibus sunt distincta . . ."; "the inner courts of houses

are of five different styles," etc.), but also from the detailed

descriptions that follow ("Testudinata vero ibi fiunt, ubi non

sunt impetus magni et in contignationibus supra spatiosae

redduntur habitationes . . ."; "Testudinate courtyards are

employed when the span is not great, and they furnish

roomy apartments in the story above").[12] In contradistinction

to the other four types in which the courtyard was only

partially roofed over, the testudinate atrium house was a

house in which the inner court was entirely covered. It was

an atrium house in which the courtyard had lost the character

of an open space by being covered over with a second

story, but it was still an atrium house.[13] The Romans used

this type of construction in houses of relatively small

dimensions, as Vitruvius himself suggests, and probably in

response to restricted land conditions prevailing in the

crowded Roman cities.

Vitruvius deals with this subject in De Architectura, Book VI,

chap. 3, par 1; cf. Vitruvii de Architectura Libri Decem, ed. F. Krohn,

1912, 129-30. Varro, in De Lingua Latina, Book V, lines 161ff, ed.

Goetz and Schoell, 1910, 49; ed. Kent, I, 1951, 150-51.

Vitruvius, loc. cit. Varro (ibid.) is even more specific: "Cavum aedium

dictum qui locus tectus intra parietes relinquebatur patulus, qui esset ad

communem omnium usum. In hoc locus si nullus relictus erat, sub divo qui

esset, dicebatur testudo ab testudinis similitudine, ut est in praetorio et

castris. Si relictum erat in medio ut lucem carperet, deorsum quo impluebat,

dictum impluvium, susum qua compluebat, compluvium: utrumque a pluvia,"

i.e., " `Inner Court' is the designation for the roofed part that is left

open within the house walls, for common use by all. If, in this, no place

was left which is open to the sky, it was called a testudo, as it is at the

general's headquarters and in the camps. If some space was left in the

center to get the light, the place into which the rain fell down was called

the impluvium, and the place where it ran together up above was called

the compluvium; both from pluvia, `rain.' "

Frank Granger, in his English version of Vitruvius' De Architectura,

(Vitruvius On Architecture, II, 1934, 25) renders "testudinate," incorrectly

as "vaulted"; Erich Stürzenacker in his German version (Marcus

Vitruvius Pollo, Über Die Baukunst, 1938, no pagination), correctly as

"ganz überdeckte Höfe"; cf. also Pauly-Wissowa, Real-Encyclopädie

der classischen Altertamswissenschaft, IX:1 (1934), col. 1063.

The Roman atrium:

an open yard developing into a covered court

Schlosser's misinterpretation of Vitruvius' and Varro's

definitions of the displuviate and testudinate Roman atrium

house was in itself conditioned by the faulty historical

assumption held by many leading classical archaeologists

at that time, that the Roman atrium was originally not a

court but the principal living room of the house which

gradually developed into an open yard.[14]

This theory was

taken up and widely propagated by one of the greatest

connoisseurs of Roman house construction, August Mau.[15]

But, curiously enough, it had not originated from any

archaeological evidence, which in fact seemed to contradict

it, but from a questionable etymological speculation by

certain Roman authors who believed that atrium came from

ater ("black") and referred to the blackening of the atrium

266. PLAN OF ST. GALL. BIRD'S-EYE VIEW OF A RECONSTRUCTION OF THE PLAN OF THE

MONASTERY

MADE FOR J. R. RAHN BY GEORG LASIUS (1876, fig. 12, 91)

This is the first, and for its period, truly outstanding attempt to show in an accurately constructed bird's-eye view, what the monastery might

have looked like had it actually been built. It formed the basis of the three-dimensional model reconstruction shown in figure 267. Rahn's

interpretation of the guest and service buildings as covered basilican structures with central hearths and openings in the roofs above, serving as

smoke escape and light inlet, was a great improvement over Keller's (fig. 264) and Lenoir's interpretation, but like theirs, suffers from being

modeled after Classical prototypes rather than those historically and archaeologically related to those of the era and location of the Plan of

St. Gall.

267. ST. GALL. HISTORICAL MUSEUM OF ST. GALL

ARCHITECTURAL MODEL. A RECONSTRUCTION OF THE BUILDINGS OF THE PLAN

The model was made by the sculptor Jules Leemann of Geneva, in 1877, on the basis of drawings furnished by Georg Lasius and has ever since

been on display in the Historical Museum of the city of St. Gall. It is a masterpiece of its kind, built to scale, and executed with supreme

craftsmanship. Length of base: 70¼ inches (1.78m). Width: 49½ inches (1.25m). The roofs of the houses, as well as the Church, can be lifted,

exposing the furniture on the ground floor levels. The second stories, the Refectory and the Cellar can be lifted out in their entirety. The

reconstruction of Church, Cloister, and Novitiate are essentially correct. The height of the Church (a little over twice the width of the nave) is

excessive for the period. The reconstruction makes no distinction between masonry and timber. Entirely unconvincing is the design of the majority

of the guest and service structures (see caption, figure 266).

of this century, this view has been increasingly challenged

by a trend of thought that holds that, on the contrary,

the Roman atrium was originally an open yard, which

gradually developed into a covered court. The main exponents

of this theory are Antonio Sogliano,[17] Giovanni

Patroni,[18] and Axel Boethius,[19] who believe the Roman

atrium house to be the product of a gradual transformation

of an early Italic farmstead, whose individual buildings

had been scattered loosely around a central open yard, into

an organized architectural system under the hands of the

Etruscan conquerors.

They assume that the principal building of this Italic

farmyard was a prostyle farmhouse with hearth and bedstead.

Through a gradual process of axial co-ordination

of this main house with the subsidiary structures and the

yard enclosure, the Etruscans, according to this theory,

developed the irregular Italic farmstead into the aggregate

depicted in figure 268. Two further developments, in their

opinion, led from this hypothetical prototype form to the

emergence of the classical Roman atrium house, the

"Pompeian primehouse"; the coalescence, namely, of the

roofs of the subsidiary structures with that of the main

house on one hand, and the roofing-over of the courtyard

on the other. As this process unfolds itself, the hearth is

shifted from the original farmhouse (now tablinum) into

one of the adjacent smaller rooms.[20]

Whatever the merits of this theory may be, this much

appears to be certain: we do not know of a single Roman

atrium house, excavated or otherwise attested, that shows

in the center of its covered court either the traces of a

hearth[21]

or any evidence in the roof above it for the existence

of a protective lantern (testudo). In the Roman atrium

house this spot is the traditional place for the catch basin

(impluvium) and directly above it, in the roof, for a rainhole

(compluvium), which also served as air or light source

(fig. 265). The hearth lay, as a rule, in one of the smaller

chambers to the side of the tablinum, or in one of the other

peripheral cubicles, but in any case entirely outside the

atrium space. The testudo of the Roman atrium house, then,

is an altogether different architectural entity from the

device that carries this name on the Plan of St. Gall. The

latter device called testu on the Plan of St. Gall is coextensive

with the hearth site (and could very well be interpreted,

as Rahn suggested, as a protective shield or lantern

that covers an opening in the roof above the hearth); the

testudo of the Roman atrium house by contrast is the designation

for a shielding roof which covers the Roman atrium,

either as a peripheral shed (as in the atrium Tuscanum) or

as a continuous roof (as in the smaller and rarer atrium

testudinatum).

This view, vigorously advanced in Ruge's article "Atrium," in

Pauly-Wissowa, II, 1896, col. 2146ff—"Der Mittelraum des altitalischen

Hauses, welcher ursprünglich den Herd enthielt, und als Speiseraum,

Arbeitsraum der Frauen, überhaupt als gemeinsamer Aufenthalt der

Hausgenossen diente"—became a commonplace in the subsequent

encyclopedic literature. It reappears in Fiechter's article "Römisches

Haus," in Pauly-Wissowa Real-Encyclopädie, 2nd ser., 1A:1, 1914,

col. 983; in Wasmuth, I, 1929, 220; in Schmitt, I Stuttgart, 1937,

col. 1197; in Encyclopedia Britannica, II, 1957, 654; and many others.

A solitary exception is Antonio Sogliano's article "atrio," in Enciclopedia

Italiana, V (Milan-Rome, 1930), 255-56, which summarizes the more

recent views ("Il megaro e il tablino sono, rispettivamente, la vera casa

di cui l'aulé e l'atrio non sono que il cortile") with bibliography concerning

the discussion of this subject prior to 1930.

Mau's widely read and repeatedly reprinted account of Pompeian

life and art, published in an English translation even before it appeared

in German, is probably the primary reason for the tenacious survival in

encyclopedic literature of the superannuated view related above. Cf.

Mau, 1899, 247, and 1904, 253; and idem, 1900, 235-36, and 1908, 258.

The principal source is Servius' Commentaries on Vergil, ed. Thilo

and Hagen, I, 1922, 202: atrium enim erat ex fumo. The derivation of

atrium from ater is only one of several derivations current among Roman

etymologists. Others thought that it came from an Etruscan town, Atria,

where the style of building is supposed to have originated: "alii dicunt

Atriam Etrurii civitatem fuisse, quae domos amplis vestibulis habebant, quae

cum Romani imitarentur, `atria' appellaverant" (ibid.). In modern

etymological literature the term has been connected with Greek αἰθριος

or ὑπαιθρἰος ("under the open sky"), which is more compatible with the

available archaeological evidence, Thesaurus Linguae Latinae, II:1,

1901, col. 1101. But even if it could be demonstrated that ater is the

correct root, we could not infer from this that in the early Roman house

the hearth stood in the atrium, since as long as the open space of the

atrium formed the principal means of escape for the smoke from the

kitchen, the walls and timbers of the court would be blackened even if

the kitchen were located in one of the peripheral chambers.

A great deal of confusion in the discussion of the Roman atrium and

its relation to the hearth has been created by a traditional misinterpretation

of verses 302-3 in book VI of Ovid's Fasti: "at focus a flammis et quod

fovet omnia, dictus; qui tamen in primis aedibus ante fuit." This passage can

under no circumstances be evidence, as Ruge suggests (above, p. 12 n.6),

for the assumption that the hearth stood in the center of the Roman

atrium, and that the latter was in the earlier days the central hearth or

living room of the house. The passage states, "The hearth (focus) is so

named after the flames, and because it warms (fovet) everything; formerly

it stood in the forward part of the house." What Ovid conveys with

this sentence is that, in contradistinction to his own days when the hearth

had no fixed position but could be found in any of the cubicles in the

immediate vicinity of the dining room (tablinum), in the early Roman

house the hearth lay always in the "forward part of the building"—a

statement that would be in full accord with the views expressed by

Sogliani, Patroni, and Boethius—if we were to assume that Ovid's

verses referred to a time in which the roof of the main house had as

yet not coalesced with that of the subsidiary structures into the complex

organism of the Roman atrium house. Cf. Ovidius, ed. Bömer,

I, 1957, 272; and Ovid's Fasti, ed. Frazer, 1951, 340.

That the Roman atrium was at that time thought of as a courtyard

and not as a room, is expressed with unequivocal clarity in Festus'

definition of "atrium": "Atrium proprie est genus aedificii ante aedem

continens aream, in qua collecta ex omni tecto pluvia descendit," i.e., "The

atrium strictly speaking is that part of the building which lies in front of

the dwelling, and contains in its center an area into which the rain

waters fall which are collected by the entire roof." Sexti Pompei Festi

De verborum significatu liber, ed. Wallace M. Lindsay (Leipzig, 1913), 12.

The views of Axel Boethius (ibid.) differ slightly from those of

Sogliano and Patroni. The primary stimulus for the development of the

Roman atrium house, according to Boethius, came from the Orient,

from a type of Near Eastern atrium house of which E. Gjerstad excavated

an excellent specimen at Vouni, Cyprus (Gjerstad, II, 1932). It is from

this type, according to Boethius, that the Etruscans drew the organizing

idea that helped to crystallize the irregular Italic prime forms into an

axially co-ordinated establishment and which, in particular, is responsible

for the tripartite room partition at the head of the atrium, opposite

the entrance (with the tablinum in the center). In essence this arrangement

is identical with that of the Vouni palace, which had three cellae

at the upper end of an open courtyard.

Whatever the differences between Patroni's and Boethius' views may

be, both hold—contrary to the traditional assumption—that the atrium

is by origin an open court that was progressively roofed over, until it

eventually took on the semblance of a room. If this assumption is correct

—and it appears to command wider and wider assent—the rain catch

basin of the Roman atrium house could no longer be considered to be

developmentally the successor of the hearth site of its Italic antecedents.

Even Mau has to admit (1908, 259), "of a hearth in the atrium not

a trace," and from this fact infers that the hearth must have been

"banished from the atrium in a comparatively early date" (idem, 1899,

237; 1904, 254). Of an overwhelming number of excavated Roman

atrium houses only two show traces of a hearth in the inner court of the

house. In one of these the hearth is not part of the original structure

(Nissen, 1877, 448); in the other it stood in one of the corners, not in the

center of the court (ibid., 431).

The ash-urn house of Poggio Gaiella

The same objections have to be raised with regard to Schlosser's

comparison of the St. Gall house with an Etruscan

ash urn from Poggio Gaiella (fig. 269) and other imitations

268. ARCHAIC ETRUSCO-ROMAN HOUSE. RECONSTRUCTION

REDRAWN FROM PATRONI, 1941, 294

Patroni's ideal conception shows the form that the early Italic farmstead had attained after individual buildings, formerly scattered loosely

around an open yard, were axially aligned into an organized architectural scheme by the Etruscan conquerors of the Italian peninsula about the

12th century B.C. The peak of Etruscan culture was achieved during the 6th century B.C.

of some Etruscan tombs. All of these specimens belong

to the courtyard type. They have an opening at the very

spot where the St. Gall house calls for a protective cover,

and there is no suggestion whatsoever that their hearths lay

under this opening or had any functional or developmental

relation to this opening. If the St. Gall house were reconstructed

analogous to the house from Poggio Gaiella, it

would have its hearth on the very spot where every squall

of rain or sleet would kill the fire and drench the occupants

of the adjacent benches and tables. As well as it may have

been adapted to the temperate conditions of a southern

climate, the layout of the house from Poggio Gaiella would

hardly meet the housing requirements of a climate where

heavy downpours and freezing temperatures are matters of

course for periods of considerable duration.

FRANZ OELMANN, 1923-1924

A shaky premise

Whatever the merits of Schlosser's theories might have

been—and even if he had been correct in his assumption

that the Etruscan and Roman atrium houses that he discussed

were of truly basilican type—a problem of major

magnitude was still presented by the formidable gap—

chronological, topographical, and cultural—that separated

Rahn's St. Gall house from its presumptive Etruscan and

Early Roman prototypes. To bridge this gap Franz Oelmann,

in 1923/24, attempted to demonstrate that houses

of the Poggio Gaiella type (fig. 269) were common in Roman

imperial times and continued to be in use in the provincial

territories of Germany and Gaul even after they had been

conquered by the Franks.[22]

Oelmann, 1923/24; and idem, 1928. The second article does not

deal with the Plan of St. Gall as such but reiterates the impluviumhearth

controversy (127ff).

A faulty interpretation of the

Gallo-Roman courtyard house

Oelmann subscribed to Rahn's idea about the St. Gall

house and felt convinced that Schlosser was right in

defining it as a descendant of the Etruscan urn house of

Poggio Gaiella, which both he and Schlosser, however,

interpreted wrongly as a structure of basilican type. Oelmann

conceded that the city of Pompeii, with all its wealth

of architectural information, "does not furnish any convincing

parallels,"[23]

then added, "but in the secular architecture,

not so much of Italy as of the Gallo-Germanic

provinces of the North, we can find analogies for practically

each and every subvariety of the houses of the Plan of St.

Gall."[24]

He undertook to support this assertion by assembling

the plans of a considerable number of Gallo-Roman

houses and juxtaposing them, type by type, with what he

believed to be their constructional counterparts on the

Plan of St. Gall. In establishing these parallels, he adopted

a procedure, as unorthodox as it is startling, by simply

reversing the views of the archaeologists by whom these

houses had been excavated. The latter were convinced that

what they had unearthed were the foundations of typical

Roman courtyard houses, i.e., houses in which the rooms

were ranged peripherally around an open central court as

in the Roman atrium house. In two of them, a farmhouse

in the vicinity of the village of Nendeln, Liechtenstein

(fig. 270),[25]

and a Roman villa in Bilsdorf, Luxembourg

(fig. 271),[26]

they had found the remains of a large impluvium,

tangible evidence of the correctness of this interpretation.

Oelmann did not conceal these facts,[27]

but simply

brushed them aside with the contention that what the

excavators declared to be an inner court was in reality a

covered hall, and that the rectangular basins found in the

center of these structures had to be interpreted not as catch

basins—as the excavators thought—but as hearths!

It is difficult for me to see how an experienced excavator [after Oelmann, 1923/24, 215, fig. 5] By von Schlosser and Oelmann misinterpreted as a structure of

would confuse the straight and careful lining of a Roman

impluvium that had never been exposed to fire with the

scorched and blackened remains of a hearth whose rims

were never as regularly set; but what makes Oelmann's

categorical reversal of the thinking of his predecessors even

more perplexing is the fact that in one case at least, namely

that of the villa at Bilsdorf in Luxembourg, the excavator

had unearthed not only the remains of the catch basin

itself, but also a good portion of its drainage ditch. In his

account of the villa of Bilsdorf, Oelmann is guilty both of

factual distortion and of suppression of vital archaeological

evidence. He does not tell us that from the presence of heat

ducts found in the walls of chambers A and J (fig. 272) the

excavators had concluded that at least the avant-corps of

the villa must have been a double-storied structure. He

leaves us in ignorance about the fact that, while many of

the peripheral rooms were carefully paved with tiles (Rooms

B, C, and F) or opus signinum (Rooms A, M, L, K, and J),

the floor of the court consisted of nothing but stamped

clay. And least to be excused, he furnishes us with a plan

269. ETRUSCAN ASH URN. POGGIO GAIELLA

basilican elevation, this house type instead had its rooms ranged

peripherally around an open inner court that was partially roofed

over like the Roman atrium house shown in figure 265.

271. BILSDORF, LUXEMBOURG [after Oelmann, 1928, 127]

270. NENDELN, LIECHTENSTEIN [after Oelmann, 1928, 127]

Oelmann's rendering of the villa at Bilsdorf is a highly simplified version of the very detailed and exemplary plan published in 1910 by its excavators, E. and R.

Malget (fig. 272). It suppresses information (given in our caption to figs. 272-273) that makes incontrovertible the fact that the inner part of the house was an open

court surrounded by a covered walk, with a center opening (IMPLUVIUM) beneath which rain collected in a catch basin (COMPLUVIUM). Thus Oelmann's interpretation

of this villa as a house of basilican design is untenable.

The Bilsdorf villa was destroyed by fire, possibly set by invading Franks, toward the end of the 3rd century A.D. A welter of skeletal remains suggests the house burned

in the course of a violent battle. Both Bilsdorf and Nendeln are typical Roman standard houses with living quarters ranging around an open inner court, of the type

commonplace throughout the length and breadth of the Roman empire. For the original excavation report on Nendeln see S. Jenny, Mitteilungen der K.K.

Central Commission, XXIII, 1897, 121ff.

units (two furnaces, one hypocaust, and one brazier) that

the excavator found in the peripheral chambers (Rooms A,

C, F, and J) and carefully recorded in his own original plan

(fig. 272). All this evidence taken into account suggests

precisely what its excavator thought it to suggest—namely,

that the villa of Bilsdorf was a classical example of the

tetrastyle Roman atrium house, i.e., a house in which a

peripheral suite of rooms, ranged all around a central open

court, was surrounded by a covered walk that had a large

rectangular opening in the middle of the roof through which

the rain drained off into a central basin in the floor beneath

it. The rooms could be heated by classical Roman heating

devices (hypocaust, furnaces, brazier), either in pairs or

individually. In the tetrastyle Roman atrium house, Vitruvius

tells us, the roof of the surrounding gallery of the

court "was supported at the angles by columns."[29] In the

villa of Bilsdorf all of the base blocks of these posts were

found still in their original emplacement. In its vertical

elevation, then, the villa of Bilsdorf bore not the slightest

resemblance to Rahn's St. Gall house, but rather might be

imagined to have looked like the house shown in figure

273.[30]

What I have tried to demonstrate with regard to the villa

of Bilsdorf holds true for all of Oelmann's other comparisons.

In not a single case could he actually demonstrate

on the basis of controllable evidence that his houses looked

as he claimed them to look; and in whatever cases I have

been able to check, his own interpretation of the facts

either contradicted that of the men by whom these houses

had been excavated or were open to at least one other

explanation.

In claiming that Oelmann's attempt to trace the missing

Gallo-Roman prototypes of Rahn's St. Gall house was a

failure, I do not mean to imply that houses of the type that

Oelmann had in mind might not have existed. But as long

as the proof of their existence rests on authoritative assertion

rather than on archaeological demonstration, I cannot

see how such a house type could be used as a prototype

form for the reconstruction of the guest and service structures

of the Plan of St. Gall.

For the farmhouse in Nendeln, cf. Oelmann, 1928, 127. The

original excavation report (Jenny, 1897, 121ff) was not available to me.

Malget, 1909. Malget's interpretation of this house as a courtyard

house was accepted by Swoboda, 1924, 112, but again rejected by Oelmann,

1928, 127.

Although he does not reveal them in each and every instance. Cases

in which he fails to bring to the reader's attention the fact that his

interpretation is in conflict with the views of the excavator are: 1) the

Roman villa near Darenth (Kent) in England, interpreted by its excavator

as belonging to a house with an open inner court (cf. Fox, 1905,

220); 2) a villa in Hagenschiessenwalde near Pforzheim (fig. 11A), also

interpreted by its excavator as a house with an open inner court (cf.

Naeher, 1885, 80); and 3) one of the service structures (No. 58) of the

great Roman villa at Anthée, Belgium (cf. Marmol, 1881, 7). There may

be more. I could not check all of Oelmann's references, since some of

the journals to which they refer are not available in the United States.

Figure 271 is Oelmann's rendering of the plan of the villa at Bilsdorf,

as reproduced in Oelmann, 1928, 127.

"Tetrastyla sunt, quae subiectis sub trabibus angularibus columnis et

utilitatem trabibus et firmitatem praestant, quod neque ipsae magnum

impetum coguntur habere neque ab interprensivis onerantur" (Vitruvii De

Architectura Libri Decem, op. cit., 129). "In the tetrastyle the girders are

supported at the angles by columns, an arrangement which relieves and

strengthens the girders; for thus they have themselves no great span to

support, and they are not loaded down by the crossbeams" (Vitruvius,

The Ten Books on Architecture, tr. Morris Hicky Morgan [Cambridge,

1926], 176).

My own suggested reconstruction. The type is very old; cf. The

Villa of Good Fortune at Olynthos, Robinson and Graham, 1938, frontispiece.

A faulty interpretation of "testu"

While Oelmann agreed with Rahn's interpretation of the

St. Gall house as a structure of basilican type, he took

exception to the latter's explanation of the testu[do] square

as a lantern surmounting a smoke hole in the roof above the

fireplace. Such a device, he claims, is attested to neither by

classical nor by medieval house construction. He suggests,

instead, that what the drafter of the Plan of St. Gall had

in mind is more likely to have been a huge freestanding

chimney stack on pillars or arches, which rose from the

ground to the ridge of the roof, protruding through the

latter, and ejected its smoke into the open air (fig. 274).[31]

But here again the reader is not furnished with any corroborating

historical evidence. That Rahn's testudines have no

equivalents in classical Greek and Roman architecture may

well be the case, but the assertion that they are not attested

Oelmann's own suggestion is concerned, it must be pointed

out that all the presumptive medieval parallels that he

adduces turn out upon inspection to pertain not to houses

but to kitchens.[33] The reader will recall that the squares on

the Plan of St. Gall which are alternately designated as

locus foci and as testu[do] are by no means confined to the

houses for distinguished persons. They are an integral part

of even the humblest among the stables. It is difficult to

imagine that an extremely tall and costly masonry stack

such as Oelmann had in mind should have adorned the

houses of swineherds, shepherds, and goatherds at a period

when such devices were a novel rarity even in the dwellings

of the nobles. Most perplexing of all, however, is

Oelmann's identification of the term testu[do] with "chimney

stack"—an equation that finds no support on any

grounds—since it is neither possible to demonstrate that

the term was ever used in this sense in classical or medieval

Latin, nor reasonable to presume that it might ever have

been used in this manner. Its basic meanings (protective

shield, covering lid, tortoise, turtle shell[34] ) are in outright

conflict with the idea of a hollow flue or duct which underlies

the concept of a smokestack.

Oelmann, 1923/24, 208 note 3; kitchen of the Cistercian monastery

of Villers, Brabant (cf. Clemen-Gurlitt, 1916, plan, fig. 102, description,

112). Oelmann's references to Durham Abbey, Durham Castle, and

Raby Castle (Archaeological Journal, LXV, 1908, 312, 322, and 328) are

so vague that it is hard to determine what he has in mind, but from the

opening words of the sentence that follows, "Über Kloster küchen im

Allgemeinen," etc., it is clear that it is the kitchens of these structures to

which he refers.

V.1.2

THE NORTHERN SCHOOL

All the theories heretofore reviewed have in common the

fact that they attempted to explain the guest and service

structures of the Plan of St. Gall in the light of house types

presumed to have existed in Etruscan, Roman, and Gallo-Roman

times. The most ardent exponent of this school,

Franz Oelmann, expressed himself in no uncertain terms

when he summarized his views with the phrase, "The Plan

of St. Gall, then, must be derived in its entirety from the

Classical tradition, i.e., from Roman architecture, and of

Northern influences . . . there can be no question whatsoever."[35]

The uncompromising fervor of this assertion is

clear evidence that at the time these lines were written, the

issue had already entered a highly controversial phase.

And indeed, as early as the last two decades of the nineteenth

century, the views of the classicists had begun to be

progressively challenged by the speculation of an opposing

school that proposed to reconstruct the guest and service

structures of the Plan of St. Gall in the light of northern

rather than classical building traditions. The seeds of this

theory may actually be discovered in the writings of some

of the exponents of the classical school. When Rahn, in

1876, interpreted the testu[do] squares as symbols for a

lantern-surmounted opening in the roof above the hearth,

he breached the thinking of the classicists, since this was a

solution suggested by analogy with northern rather than

with southern building types. Yet, apart from this "intrusive"

detail, Rahn's reconstruction was essentially a product

of the classical school. A square attack on the theories

of the latter, however, was launched in 1882 by Rudolf

Henning.

RUDOLF HENNING, 1882

In a study entitled "Das Deutsche Haus in seiner historischen

Entwickelung,"[36]

Rudolf Henning stressed the resemblance

of the plan of the St. Gall house to certain

house types still used in Upper Germany and in Switzerland,

in territories once occupied by Frankish, Alamannic,

and Bajuvarian tribes. In dwellings of this type (fig. 275)

such as is exemplified by a house from the Engadin in

Switzerland, the hearth is, as a rule, located in a common

center room (Eren) from which access is gained to all the

subsidiary outer rooms. It is surmounted by a wooden

smoke flue of pyramidal shape which projects beyond the

roof like a chimney and can be closed and opened by an

adjustable lid. A similar arrangement is found even today

in old farmhouses of Denmark (fig. 276). Henning did not

propose that the St. Gall house was equipped with such a

smoke flue. He believed, on the contrary, that it had an

open hearth and, in the roof above the hearth, a lantern-surmounted

opening that served as a smoke outlet and as a

light source. He imagined the St. Gall house to have been a

spacious, steep-roofed structure with inner wall partitions

that did not obstruct the view of its enclosing walls and

rafters. He felt supported in this assumption by a passage

in the Lex Alamannorum which makes the paternal right

of inheritance dependent on the ability of the newborn

child to encompass the roof and the four corners of the

house as he opens his eyes.[37]

The existence of a house of

this description, Henning felt, must be postulated as the

medieval prototype form of the modern Swiss and Upper

BILSDORF (HAUTE SURE), LUXEMBOURG. PLAN OF A ROMAN VILLA

272.A

272.B

[redrawn after Malget, 1909, 354]

Malget describes features of the villa's rooms:

A. Heatable room with brick-column supported, raised floor of limestone-bedded,

crushed rubble. Within it: socle for an altar (a); brick-paved area for the

brazier probably used to heat the room (m); tile smoke flues (d).

B. Room with limestone-bedded crushed rubble floor.

C. Tile-paved room with hypocaust, heated by furnace (e).

D. Room with crushed brick floor.

E. Lodging for slaves (floor material not identified).

F. Room paved with rectangular brick.

G. Unpaved room, probably for slaves assigned to heat F.

H. Room paved with stamped clay; I, room paved with stamped clay, probably,

for slaves heating J.

J. Warming room over hypocaust heated by furnace in I, with raised floor

(unidentified substance) supported on brick columns.

of the subsidiary outer rooms; and, in the houses of

the Plan of St. Gall, he believed to have discovered the

first pictorial evidence of this prototype form. The development

that leads from this archetype to its modern derivative,

Henning assumed, was characterized by the gradual

substitution of a stone-built stove with smoke flue for the

originally open fireplace, and by the removal of the light

source from the ridge of the roof to the walls, which became

necessary when the opening in the ridge was obstructed by

the installation of a central smoke stack.

The beginnings of this displacement of the open fireplace

by stone-built stoves, Henning suggested, may already be

observed in some of the more distinguished structures of

the Plan of St. Gall, such as the House for Distinguished

Guests, where the common central fireplace is already

supplemented by stone-built corner fireplaces.

KARL GUSTAV STEPHANI, 1902-1903, AND

CHRISTIAN RANCK, 1907

Henning refrained from embodying his ideas about the

St. Gall house in a visual form, and in the fifty years that

followed, this theory found neither support nor acceptance.

The views expressed in Karl Gustav Stephani's encyclopedic

work on the early German dwelling and its furnishings,[38]

as well as those in Christian Ranck's percursory but

widely read cultural history of the German farmhouse,[39]

are literal repetitions of Julius von Schlosser and show that

273. BILSDORF (HAUTE SURE), LUXEMBOURG. PERSPECTIVE VIEW

AUTHORS' RECONSTRUCTION

K. Vestibule with damaged crushed rubble floor.

L. Water basin reached from K by steps paved in square brick.

M. Entrance hall with concrete floor of limestone, broken brick, and sand on a

dry-stone bed.

N. Rain catch-basin (impluvium) set in a square of opus signinum; the rest of

the atrium was paved with red clay. (Judging from the many pieces of

slate found scattered through the atrium, we may assume the house was

roofed in slate.)

Figure 273:

Of square plan but for the generous setback of the entrance wing, the villa's

size (over 80 × 80 feet on the ground floor) and its double-storied corner wings

made it a structure of imposing presence. The reconstruction above is based on

Malget's description, which holds a wealth of specific detail.

German house was still entirely under the spell of the

thinking of the classicist. But in the third decade of this

century, the method that Henning had initiated, namely,

that of attempting to reconstruct the St. Gall house in the

light of its modern derivatives rather than of its historical

prototypes, found a sudden revival in a number of visual

reconstructions that marked a complete departure from

the thinking of the classical school. These reconstructions

(figs. 277-281) came from the hands of men who were not

primarily historians but professional architects, and they

were the product of intuitive speculation rather than of

documentative historical study. The first of these was made

by H. Fiechter-Zollikofer in 1936.

H. FIECHTER-ZOLLIKOFER, 1936

Mr. Fiechter-Zollikofer, a Swiss engineer, wrote an article

entitled "Etwas vom St. Galler Klosterplan aus der Zeit

um 820," which was published in the Schweizerische Technische

Zeitschrift,[40]

a journal not normally read by the

architectural historian of the Middle Ages. In this article

Fiechter-Zollikofer reproduced not only an over-all reconstruction

of the entire monastery shown on the Plan of St.

Gall, in bird's-eye view (fig. 277), but also a separate reconstruction

of the exterior of the Outer School (fig. 278), the

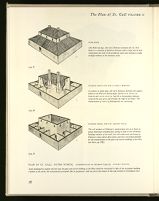

PLAN OF ST. GALL. OUTER SCHOOL. INTERPRETATION OF OELMANN (1923-4). AUTHORS' DRAWING

274.C WITH ROOFS

Like Rahn (see figs. 266-267) Oelmann interprets the St. Gall

house as a structure of basilican elevation with a large central hall

rising above the roofs of the perpheral rooms and receiving its light

through windows in the clerestory walls.

274.B WITHOUT ROOFS AND WALLS PARTLY REMOVED

In contrast to Rahn (figs. 266-267) Oelmann interprets the squares,

which on the Plan are alternatingly referred to as TESTU (i.e.

lantern) and LOCUS FOCI (i.e. hearth) as freestanding chimneys

rising all the way up to and through the ridge of the house. This

interpretation of TESTU is philologically not convincing.

274.A WITHOUT ROOFS, AND FULL HEIGHT WALLS

The real weakness of Oelmann's interpretation lies in its bases on

purely theoretical considerations, giving no heed to the vernacular

building tradition of the north (not well understood and known in

Oelmann's days) which offers better and more convincing parallels

for the interpretation of the guest and service buildings of the Plan

(see below, pp. 88ff).

Until challenged by student who felt that the guest and service buildings of the Plan should be interpreted in light of the vernacular building

tradition of the north, this interpretation prevailed. But its proponents could not prove that houses of this type existed in Carolingian times.

of perspectives and cuts of the church and the claustral

structures.

Fiechter-Zollikofer was convinced that the traditional

concept of the St. Gall house as a dwelling that received

its light in the Italian manner through windows in its

clerestory walls was incompatible with the climatical conditions

prevailing in transalpine Europe, and that a solution

infinitely better adapted to the rain and snowswept foothills

of the Alps could be found if the St. Gall house were

reconstructed in the light of certain rural timber dwellings

still used in many districts of Switzerland.

Accordingly, he reconstructs the St. Gall house as a

low-roofed, low-walled gable house of logs with corner-timbered

protruding beams (fig. 278). The center room

of this house receives its light through a large tapering

shaft mounted upon the ridge of the roof which could be

opened and closed through an adjustable lid (fig. 279); the

outer rooms were lighted through windows in the peripheral

log walls. Fiechter-Zollikofer's reconstruction is the first

attempt to interpret the guest and service structures of

the Plan of St. Gall in the light of an actually existing

vernacular house type. It is a handsome reconstruction,

but the prototype after which it is modeled, the Alpine

log house, is too closely associated with local conditions to

have been adopted in a master plan that was drawn up for

the whole of the Frankish empire. Log construction depends

on abundant stands of fir trees, such as are available in the

Alps, the Black Forest, and the mountain ranges of Scandinavia;

but in the lowlands this material was lacking.

Moreover, Fiechter-Zollikofer did not enter into any

detailed analysis of the internal layout of these houses. He

did not support his reconstructions with any specific parallels

with comparable structures still in existence, or attempt

to trace this house type to its historical past.

OTTO VÖLCKERS, 1937

Fiechter-Zollikofer's article had barely been published when [after Henning, 1882, 150, fig. 62] Plan of a Swiss house of relatively recent date with an open hearth [after Steensberg, 1943, 20, fig. 7] A north European variant of the house type shown in figure 275. A BAKING OVEN B MALT KILN C KETTLE D FIRE RECESS E HEATER F MANTLE

the German architect, Otto Völckers, touched upon the

problem of the St. Gall house in a small, handsomely

illustrated book in which he reviewed the history of the

European house from the Stone Age to the present.[41]

Völckers exemplified his views with a reconstruction of

St. Gall's House for Distinguished Guests (fig. 280). This

he imagines to have been a steep-roofed structure, hipped-over

on the narrow ends of the building. The walls are low

and masonry-built with windows giving light to the external

rooms. The center room is lighted by an opening in the

ridge above the hearth site, which also serves as a smoke

outlet and is surmounted by a small protective roof that

shields the opening against any downpour. The heating

units in the bedrooms of the distinguished guests are

interpreted as corner fireplaces with masonry stacks protruding

through the roof above them. Völckers did not discuss

275. ENGADIN, SWITZERLAND

in a common center room that gives access to all of the outer rooms.

The hearth is surmounted by a wooden smoke flue of pyramidal

shape that projects beyond the roof.276. DANISH FARM HOUSE

Chimney-surmounted hearths of this type work well in relatively

small houses, but would involve constructional hazards of frightening

magnitude in most of the larger houses of the Plan of St. Gall.

277. PLAN OF ST. GALL. BIRD'S-EYE VIEW OF THE MONASTERY

RECONSTRUCTION BY FIECHTER-ZOLLIKOFER [1936, 405, fig. 2]

A great advance over the reconstructions offered by the classicists (figs. 266, 267 and 274) and the first attempt to interpret the guest and

service structures of the Plan of St. Gall in the light of an existing building tradition—wholly workable in structural terms, yet too dependent

on local alpine conditions (log construction) to be applicable to a document worked out in the heart of the Frankish Empire and conceived to

reflect more general conditions.

interior view of the dining room (fig. 281) which he published

in a subsequent book,[42] he appears to think of the

inner wall partitions as likewise being built as solid masonry

walls.

KARL GRUBER, 1937

The same year that Völckers published his pictorial review

of the history of the German house, and probably independent

of both Völckers' and Fiechter-Zollikofer's proposal,

Karl Gruber published still another reconstruction of the

Plan, in bird's-eye view, in a superbly illustrated book,

entitled Die Gestalt der deutschen Stadt (fig. 282).[43]

Like

Fiechter-Zollikofer, Gruber reconstructs the St. Gall house

as a house with low pitched roof and straight gable walls on

the narrow sides. It receives its light from windows in the

supporting walls and emits the smoke of its hearth through

a louver in the ridge of the roof. The latter, as in Völckers'

reconstruction, is rendered as a miniature roof, raised above

the level of the main roof to protect the opening over the

hearth site. Gruber is not specific about the material used

in the construction of his houses. The uniform mode of the

rendering of the walls suggests that he thought of them as

being built in masonry.

V.1.3

A RENASCENCE

OF THE CLASSICAL SCHOOL

ALAN SORRELL, 1966

The interpretations of Fiechter-Zollikofer (1936), Völckers

(1937), and Gruber (1937) represented a radical departure

278. PLAN OF ST. GALL. OUTER SCHOOL

[Interpretation by Fiechter-Zollikofer, 1936, 407, fig. 6]

The St. Gall house is here reconstructed as a low-roofed, low-walled

gable house, of log construction, the center room receiving its light

through a tapering wooden shaft mounted upon the ridge of the

roof (see fig. 279).

to Roman or Gallo-Roman house construction. In 1965

this trend was reversed by a dramatic reconstruction painting

published in a beautifully illustrated book, The Dark

Ages, under the general editorship of a distinguished

Byzantinist, David Talbot Rice.[44] The painting (fig. 283)

carries the signature of Alan Sorrell and is executed in the

flamboyant chiaroscuro that characterizes the hand of this

great interpretive draftsman to whom we owe so many

other impressive reconstructions of medieval and Anglo-Roman

buildings now in ruin.

Unluckily, the scholarship that accompanied this drawing [Redrawn from Fiechter-Zollikofer, 1936, 406, fig. 5] 279.A 279.B Detail of the tapered wooden shaft that serves as light inlet and

is not commensurate with the skill of its draftsmanship.

The Church with its steep proportions and its elaborate

blind relief of pilasters and arches looks more like a

Romanesque cathedral than a Carolingian monastery

SMOKE OUTLET AT RIDGE OF ROOF

smoke escape in the houses shown in the two preceding figures. The

lid that covers the opening can be opened and closed with the aid of

chains.

keepers which occupy the tract to the west of the Church,

conversely, is a return to the superannuated concept of the

courtyard house, proposed by Keller in 1844 and by Lenoir

in 1852. The majority of the guest and service structures

are rendered as buildings of basilican design, in conformity

with the views expressed by Rahn in 1876, Schlosser in

1889, and Oelmann in 1923-4. Sorrell was obviously not

familiar with any of the reconstruction drawings published

by the opposing school (Fiechter-Zollikofer, Völckers, and

Gruber), nor for that matter with a reconstruction of my

own published by Poeschel in 1957 and by myself in 1958.[45]

280. PLAN OF ST. GALL. EXTERIOR PERSPECTIVE

HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

[as interpreted by Völckers, 1949, 34]

Völkers reconstructs the St. Gall house—correctly in our opinion—as a

steep-roofed structure hipped at the narrow ends, its center room lighted

by an opening in the ridge that is surmounted by a small protective roof.

281. PLAN OF ST. GALL. INTERIOR PERSPECTIVE

HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

[as interpreted by Völckers, 1949, 18]

The large center hearth on the Plan is termed "locus foci." Along the

walls are tables and benches where visitors and their servants take meals.

The rooms under the hipped portions of the roof are heated by their own

fireplaces.

the description of the Plan published in 1848 by Robert

Willis, who recognized that Keller's interpretation of the

St. Gall house as a courtyard house conflicted with the

inscriptions of the Plan, but did not relinquish this interpretation

in the case of houses for animals and their keepers.

V.1.4

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Thus, by the sixth decade of this century the discussion

of the guest and service structures of the Plan of St. Gall

still remains stalemated by two opposing schools. The

classicists had tried to explain the St. Gall house in the

light of a presumptive Roman or Romano-Etruscan type

of house that antedated the Plan of St. Gall by over a

millennium, and whose existence they could not really

prove. On the other hand, the house types on which the

reconstructions of the opposing school were based reached

no further back than the sixteenth, or at best, the end of

the fifteenth century. The proponents of neither of these

two contending approaches were able to demonstrate that

the type of building they had in mind was actually in use

at the time the Plan was drawn. And the great cultural

alternative that Henning had raised in 1882—the suggestion

that the guest and service structures of the Plan of

St. Gall should be interpreted in the light of northern

building tradition rather than in the light of classical

Roman architecture—still loomed as an unsolved problem

over the entire controversy.

Oelmann had summarized this condition correctly in

1923-4, by stating, "The entire quibble about the Northern-Germanic

or Southern-Roman derivation will only be

decided once the existence of layouts that correspond

exactly can be proven in either one or the other area."[46]

However, he added to this statement a passage of questionable

validity when he amplified it with the remark, "The

North is totally excluded, for neither are any contemporary

house remains preserved which would be worthy of mention,

nor is it possible to infer from later specimens earlier forms

of an identical type."

Doubtful in 1923-4, Oelmann's latter idea had become

untenable by 1971 (when this chapter was written).

It is true that at the time of Oelmann's writing research

into the problem of the Northern house was still in its

infancy. Nevertheless, some significant discoveries about

transalpine house construction in the Middle Ages had

already been made in Sweden and on the islands of Gotland

and Iceland.[47]

To be sure these were few and scattered;

282. PLAN OF ST. GALL. BIRD'S-EYE VIEW OF THE MONASTERY

RECONSTRUCTION BY KARL GRUBER (1937, 25, fig. 15)

This handsome reconstruction was published in the same year that Otto Völckers published his reconstruction of the St. Gall house (figs. 280-81).

In structural terms Gruber's concept is as workable as that of Völckers and Fiechter-Zollikofer (figs. 277-278), but the conjecture that the guest

and service buildings would all have been constructed in masonry in a part of the world where houses were by tradition built in timber (see

pp. 23ff) is unconvincing.

Very interesting and historically defensible, but not supported by the Plan itself (see I, 163ff) is Gruber's conjecture of a tower over the

intersection of nave and transept. Abbot Haito's church at Reichenau (I, fig. 117) and the abbey church of St. Riquier (I, fig. 196) had such

towers.

283. PLAN OF ST. GALL. BIRD'S-EYE VIEW OF THE MONASTERY

RECONSTRUCTION. PERSPECTIVE BY ALAN SORRELL (Rice, 1965, 279-280)

The design of the houses for animals and their keepers (foreground) is based on the superannuated concept of the courtyard house, proposed by

Keller in 1844 (fig. 264). Most of the other houses are interpreted as basilican structures, in conformity with suggestions made by Rahn in

1876 (fig. 266), Schlosser in 1889, and Oelmann in 1923-24 (fig. 274). Sorrell was not familiar with the writing and reconstructions of scholars

who interpreted the St. Gall house in the light of northern building traditions (fig. 277, 278, 280).

material was made good to a considerable extent by the

availability of a substantial body of literary and textual

references to house construction which had been touched

upon as early as 1882 by Rudolf Henning[48] and was discussed

at length in 1902-3 by Karl Gustav Stephani's

comprehensive treatise on the German dwelling.[49]

During the last three decades this material has been

enriched by a veritable flood of archaeological discoveries

bearing upon the problem. As I propose to deal with this

material at length in a separate study, I shall review it here

only to the extent necessary for the typological identification

of the guest and service structures of the Plan.

I refer to such excavations as had been conducted in Sweden as

early as 1886 by Frederik Nordin ("Gotlands s.k. Kämpagrafvar," in

Mânadsblad, Kungl. vítterhets ok antîkvîtets akademíen [Stockholm,

1886], 145ff; 1888, 49ff; and idem, En svensk Bondgârd for 1500 âr

sedan [Visby, 1891]); in Iceland as early as 1895 (cf. Thorsteinn Erlingsson,

Ruins of the Saga Time [London, 1899]); and during the first two

decades of this century in such places as Augerum in Blekinge, Sweden

(cf. Otto Montelius, Kulturgeschichte Schwedens [Leipzig, 1906], 283,

fig. 451); and Rings in Hejnum, Sweden (on the latter, cf. Vallhagar, ed.

Stenberger and Klindt-Jensen, II, 1955, 864ff).

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||