The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V.1.1.. |

| V.1.2. |

| V.1.3. |

| V.1.4. |

| V. 2. |

| V.2.1. |

| 10. |

| 10. |

| V.2.2. |

| V. 3. |

| V.3.1. |

| V.3.2. |

| V.3.3. |

| V. 4. |

| V.4.1. |

| V.4.2. |

| V.4.3. |

| V. 5. |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

| V. 6. |

| V.6.1. |

| V.6.2. |

| V.6.3. |

| V.6.4. |

| V. 7. |

| V.7.1. |

| V.7.2. |

| V.7.3. |

| V.7.4. |

| V.7.5. |

| V.7.6. |

| V. 8. |

| V.8.1. |

| V.8.2. | V.8.2 |

| V.8.3. |

| V.8.4. |

| V.8.5. |

| V.8.6. |

| V.8.7. |

| V.8.8. |

| V. 9. |

| V.9.1. |

| V.9.2. |

| V.9.3. |

| V. 10. |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. |

| V. 11. |

| V.11.1. |

| V.11.2. |

| V.11.3. |

| V. 12. |

| V.12.1. |

| V.12.2. |

| V.12.3. |

| V. 13. |

| V.13.1. |

| V.13.2. |

| V. 14. |

| V.14.1. |

| V.14.2. |

| V. 15. |

| V.15.1. |

| V.15.2. |

| V.15.3. |

| V.15.4. |

| V. 16. |

| V.16.1. |

| V.16.2. |

| V.16.3. |

| V.16.4. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| V.18.1. |

| V.18.2. |

| V.18.3. |

| V.18.4. |

| V.18.5. |

| VI. |

| VI. 1. |

| VI.I.I. |

| VI.1.2. |

| VI.1.3. |

| VI.1.4. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI.2.1. |

| VI.2.2. |

| VI.2.3. |

| VI.2.4. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI.3.1. |

| VI.3.2. |

| VI.3.3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI.4.1. |

| VI.4.2. |

| VI.4.3. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

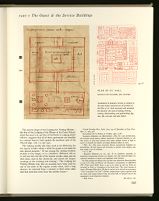

V.8.2

LODGING FOR VISITING MONKS

The synod of 817 prescribed that each monastery should be

provided with special quarters for the reception of the

visiting monks: "Ut dormitorium iuxta oratorium constituatur

ubi superuenientes monachi dormiant."[284]

Hildemar, in

his commentary on the Rule of St. Benedict (written between

845 and 850 at the monastery of Civate in Italy),

furnishes us with some further detail on this subject.[285]

The

brothers, he tells us, should never be quartered with any

laymen (not even with the vassalli by whom they may be

accompanied) as the latter often stay awake until midnight,

passing their time in idle talking and jesting, while the

monks should spend it in silence and prayer.[286]

For this

reason their Dormitory should be next to the church, so

that they can enter the sanctuary at any time of the day and

night.[287]

In compliance with these stipulations a Lodging for

Visiting Monks is established on the Plan of St. Gall, in the

corner between the northern transept arm and the northern

aisle of the Church (fig. 391). It consists of a long and narrow

apartment, 10 feet wide and 50 feet long, which is internally

divided into a living room (susceptio fr̄m̄ supuenientium) and

a dormitory (dormitoriū eorum), both of equal dimensions. The

living room is furnished with two wall benches and from

it direct access is gained to the Church through a door

which leads into the northern transept arm. The dormitory

has a privy attached to it (necessarium); and the number of

beds that it contains suggests that the maximum number of

daily visitors who could be expected from other convents

was six.

PLAN OF ST. GALL

392.

391.X

HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS

Installation of auxiliary services in annexes to

the main houses characterizes all facilities of

the Plan of St. Gall associated with potential

fire hazards: the tasks of baking, brewing,

cooking, blacksmithing, and goldsmithing (figs

292, 396, 419-421, and 462, below).

The narrow shape of the Lodging for Visiting Monks—

like that of the Lodging of the Master of the Outer School,

which lies next to it, and that of the Porter's Lodging which

follows—suggests that all of these apartments are installed

in a narrow lean-to, built against the northern aisle of the

Church (figs. 108, 112 and 191).

The visiting monks take their meal in the Refectory for

the regular monks, where a table for guests is set aside for

that special purpose.[288]

If one among the visiting brothers

decides to stay longer, or is a familiaris, Hildemar tell us,

he will join into the life of the regular monks, sleep and eat

with them, read in the claustrum, and attend the chapter

meetings in the morning and evening.[289]

The Lodging for

Visiting Monks may also on occasion have been used by

one or the other of the regular monks when, after a long

absence, he returned from a journey or from some other

task that took him away from the mother house.[290]

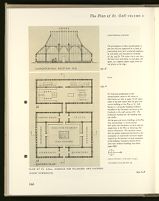

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS

393.B LONGITUDINAL SECTION

The presumption in these reconstructions is

that the roof was supported by a frame of

freestanding inner posts connected lengthwise

by roof plates and crosswise by tie beams

(cf. fig. 393.D). The rafters rise in two tiers,

the lower from wall plates to roof plate, the

upper, at a slightly steeper angle, from the

roof plates to the ridge.

393.A PLAN

For historical justification of the

reconstructions shown in this series of

illustrations we refer to pages 72-82 above,

where it has been shown that the guest and

service buildings of the Plan of St. Gall

belong to a vernacular building tradition

traceable in the Germanic territories of the

Lowlands to the 14th century B.C. The

traditional material for this building type

was timber.

All the guest and service buildings of the Plan

were freestanding; in reconstructing

their plans and elevations, we have used the

simple lines of the Plan as indicating their

interior dimensions. The elevations shown

here are purely conjectural but based on the

assumption of comfortable minimum heights

required by the functions of each component

of the building. Carpentry details derive

from later medieval buildings (see above,

pages 88ff).

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS

393.C EAST ELEVATION

The roof lines might have been straight. We

have chosen to show them broken, because

they thus reflect more clearly in the exterior

appearance of the building the composition

and boundary lines of its inner spaces. To

hip the roof over the narrow ends of the

building is a sound constructional assumption,

since it steadies the roof in the longitudinal

orientation and is a feature archaeologically

well attested as early as the Iron Age.

393.D TRANSVERSE SECTION

393.E NORTH ELEVATION

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

PLAN OF ST. GALL. LODGING OF THE MASTER OF THE HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS & PAUPERS

394.A

394.B

The nature of his duties required that the caretaker of the poor have his own lodging, a

simple rectangular room with corner fireplace installed as a lean-to abutting the south aisle

of the church and about 15 feet from the Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers. The porch

through which pilgrims and paupers entered was an access to be shared by them with the

monastery's workmen and tradesmen, and by other lay visitors such as relatives of the

brothers, who might enter through that porch and then converse with their kin in the Monks'

Parlor next to and east of the Hospice. No outsider went beyond this Parlor without

escort.

The Master of the Hospice was assisted by servants lodged in the eastern aisle of the

Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers. The suggested circulation patterns show with what

relative ease the congress of the monastery with the world might be controlled. Confined on

the east by the Cellar wall and on the south by a (presumptive) fence, travelers could

enter the areas around the Hospice, dine in the house provided for their needs, rest,

exchange news and gossip of the day, and move on, all without disturbing the more orderly

life going forward in the calm heart of the monastery.

1. Church- Ig. Porch of Reception- WP western paradise- I1. Tower of St. Gabriel- Ih.

Porch to Hospice- Ii. Lodging, Master of Hospice for Pilgrims & Paupers- 31. Hospice

for Pilgrims & Paupers- 32. Kitchen, Bake & Brewhouse for Pilgrims & Paupers.

Expositio Hildemari, ed. Mittermüller, 1880, 611: quia dormitorium,

ubi monachi suscipi debent, habetur separatum a laicorum cubiculo, i.e. ubi

laici jacent, eo quod laici possunt stare usque mediam noctem et loqui et

jocari, et monachi non debent, sed magis silentium habere et orare.

Ibid., 612: Ideo juxta oratorium illorum monachorum hospitum est

dormitorium, ubi ipsi jaceant soli reverenter, et possint nocte surgere, qua

hora velint, et ire in ecclesiam.

Expositio Hildemari, ed. cit., 582: Si est familiaris monachus, in

dormitorio monachorum dormit et in claustra cum aliis monachis legit et in

refectorio manducat et mane et ad capitulum venit fratrum.

On Irish monks and abbots who, on their way back from Rome decided

to stay in St. Gall, see Meyer von Knonau's commentary on Ekkeharti

(IV). Casus sancti Galli, chap. 2, pp. 9-10, notes 33 and 34. They are

recorded as Scotti or Scotigenae in the death lists. The most famous of

these is Moengal-Marcellus, (Notker's teacher) who visited the monastery

"of his compatriot St. Gall" (Gallum compatriotam suum) together with

his uncle, and stayed behind when the latter left, to become one of the

monastery's most illustrious teachers.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||