V.7.5

BAKING OVENS

On the Plan of St. Gall there are three baking ovens (fig.

382A-C): one in the Monks' Bake and Brew House

(caminus); one in the Bake and Brew House for Distinguished

Guests (fornax); and one in the Bake and Brew

House for Pilgrims and Paupers (fornax). They have diameters,

respectively, of 10 feet, 7½ feet, and 7½ feet.

The baking of bread is one of the most ancient of human

arts. Calcined remains of unleavened bread made from

crushed grain were found in Swiss lake dwellings that date

from the early Stone Age.[265]

Reference by implication to the

custom of leavening (i.e., admixing to the dough a substance

that produces gases, thus causing the bread to rise)

is made in Genesis, where it is said of Lot that "he made

them a feast, and did bake unleavened bread."[266]

One very

early baking method, perhaps the first devised, was that of

placing the dough on a heated flat or convex stone and

covering it with hot ashes.[267]

The size and number of loaves

that could be baked in this manner was limited by the shape

of the stone. To bake in quantity required the invention of

the oven, a round or ovoid chamber that held the heat and

allowed it to be distributed over a wider surface. One of the

earliest Central European ovens was excavated in the Stone

Age settlement of Taubried, on Lake Federsee, Germany

(fig. 383).[268]

The walls of the baking chamber were made of

daubed wattle. The opening in front was covered with a

removable shutter, probably of wood and cloth.

Between the third millennium B.C. and the middle of the

nineteenth century A.D., neither the shape of the oven nor

the method of baking changed significantly. A circular oven

of baked brick, dating from the beginning of the second

millennium B.C., was found by André Parrot[269]

during his

excavation of the Palace of Mari, Mesopotamia, (fig. 386)

in a bathroom of the quarters of the superintendent of

the palace (cf. fig. 372). A Roman oven shaped exactly like

this one is shown on a frieze of the monument of the baker

Eurysaces at Rome, dating from the first century B.C. (fig.

385).[270]

On the left, the baker is placing the loaves in the

oven. On the right, four men are kneading dough on a table.

Primitive clay ovens of the Taubried type (fig. 383) are

still in use today

[271]

and were unquestionably common in

medieval times. Figure 384 shows the reconstruction of a

Langobardic oven of this type from the first century A.D.

[272]

A handsome illustration in the Behaim Codex in Krakow

(fig. 387)

[273]

shows the baker placing the loaves in the oven,

his helper shaping them, and a woman throwing some salt

or herbs into the dough rising in a kettle on the floor in

front of the oven. The oven is built into the corner of this

copper-roofed shed. The smoke rises from a round hole in

the top of the oven and passes through a dormer window

in the roof out into the open. Figure 388 shows a baking

scene that occurs among the representations of the planet

children of Saturn in a manuscript in the University Library

at Tübingen.

[274]

Here again the smoke escapes through circular

openings in the top of the baking chamber. Ovens of

this same design are found in other medieval illuminations.

[275]

[ILLUSTRATION]

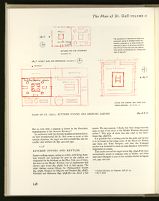

389. E, F, G PLAN OF ST. GALL. KITCHEN STOVES AND BREWING RANGES

But an oven with a chimney is shown in the December

representation of the Grimani Breviary.

[276]

In conformity with the pictorial tradition reviewed above,

we have reconstructed the St. Gall ovens as more or less

circular chambers, the larger one with a smoke flue, the two

smaller ones without (cf. figs. 402 and 394).