The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V.1.1.. |

| V.1.2. |

| V.1.3. |

| V.1.4. |

| V. 2. |

| V.2.1. |

| 10. |

| 10. |

| V.2.2. |

| V. 3. |

| V.3.1. |

| V.3.2. |

| V.3.3. |

| V. 4. |

| V.4.1. |

| V.4.2. |

| V.4.3. |

| V. 5. |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

| V. 6. |

| V.6.1. |

| V.6.2. |

| V.6.3. |

| V.6.4. |

| V. 7. |

| V.7.1. |

| V.7.2. |

| V.7.3. |

| V.7.4. |

| V.7.5. |

| V.7.6. |

| V. 8. | V. 8 |

| V.8.1. |

| V.8.2. |

| V.8.3. |

| V.8.4. |

| V.8.5. |

| V.8.6. |

| V.8.7. |

| V.8.8. |

| V. 9. |

| V.9.1. |

| V.9.2. |

| V.9.3. |

| V. 10. |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. |

| V. 11. |

| V.11.1. |

| V.11.2. |

| V.11.3. |

| V. 12. |

| V.12.1. |

| V.12.2. |

| V.12.3. |

| V. 13. |

| V.13.1. |

| V.13.2. |

| V. 14. |

| V.14.1. |

| V.14.2. |

| V. 15. |

| V.15.1. |

| V.15.2. |

| V.15.3. |

| V.15.4. |

| V. 16. |

| V.16.1. |

| V.16.2. |

| V.16.3. |

| V.16.4. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| V.18.1. |

| V.18.2. |

| V.18.3. |

| V.18.4. |

| V.18.5. |

| VI. |

| VI. 1. |

| VI.I.I. |

| VI.1.2. |

| VI.1.3. |

| VI.1.4. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI.2.1. |

| VI.2.2. |

| VI.2.3. |

| VI.2.4. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI.3.1. |

| VI.3.2. |

| VI.3.3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI.4.1. |

| VI.4.2. |

| VI.4.3. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V. 8

FACILITIES FOR THE RECEPTION

OF VISITORS

V.8.1

THE MULTIFARIOUS ACCOMMODATIONS

The reception and care of guests, wealthy and poor, was

one of the primary duties of a monastic community. About

the proper performance of this service St. Benedict spoke

in emphatic terms: "Let all guests that come be received

like Christ, for he will say I was a stranger and ye took me

in."[278]

He asks that "fitting honors be shown to all," but

especially to churchmen and pilgrims[279]

and demands that

special care be given to the reception of the poor "because

in them is Christ more truly welcomed; for the fear which

the rich inspire is enough in itself to secure them honor."[280]

He rules that the guests be served from a separate kitchen,

"so that the brethren may not be disturbed when guests

arrive at irregular hours,"[281]

and he places the responsibility

for the reception of the visitors in the hands of the Porter.[282]

390. LUTTRELL PSALTER

LONDON, BRITISH MUSEUM. ADD. MS. 42130, fol. 207

[after Millar, 1932, pl. 166]

The open kettles in this margin illumination appear to be supported on stands,

with open fires below them. The arcuated ranges of the Plan were considerably

more sophisticated; the Luttrell Psalter illuminations date to 1340.

The protection of paupers and pilgrims was also a concern

of the secular ruler—a responsibility that the emperor

had taken upon himself through his coronation in Rome,

as the holder of a universal power that obliged him to

protect and promote the Christian faith. It is defined as

such in a capitulary issued by Charlemagne in 802: "That

no one shall presume to rob or do any injury fraudulently

to the churches of God or widows or orphans or pilgrims;

for the lord emperor himself, after God and His saints, has

constituted himself their protector and defender."[283]

On the Plan of St. Gall there are no fewer than seven

separate installations devoted to monastic hospitality and

its administration. Listed in the order of prominence with

which they were associated in the thinking of St. Benedict

they are:

1 The Lodging for Visiting Monks

2 The Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers, with an annex

containing the Kitchen, the Bake and Brew House for the

Pilgrims and Paupers3 The Lodging of the Master of the Hospice for Pilgrims

and Paupers4 The Porter's Lodging

5 The House for Distinguished Guests, with annex

containing the Kitchen, Bake and Brew House for the Distinguished

Guests6 The House for Servants of Outlying Estates and for

Servants Traveling with the Emperor's Court7 The House for the Vassals and Knights who travel in

the Emperor's Following

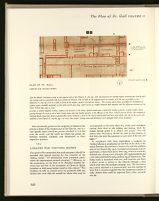

391. PLAN OF ST. GALL

LODGING FOR VISITING MONKS

Like the Monks' Dormitory lying on the opposite side of the Church (I, 260, fig. 208), the quarters for visiting monks communicate directly with

the transept and are accessible only from within the Church. The six beds in the lodging accord in number with the seats available in the

Refectory (I, 263, fig. 211) at a table in front of the reader's lectern reserved for visitors. The visiting monks have available for recreation an

outdoor space, probably gardened, 7½ feet wide and 80 feet long, which serves as a buffer between their quarters and the adjacent enclosure of the

Outer School (fig. 409, p. 174).

In order to attend religious services, students and teachers in the Outer School would have crossed this outdoor area for visiting monks, thence

passing through the eastern end of their living room. Like the nearby quarters of the Master of the Outer School and the Porter, the Lodging of

Visiting Monks must have been at ground-floor level, doubtless a lean-to the roof of which could not have risen above the sills of the north aisle

windows of the Church (I, 165-66, figs 111-112). The visitors' living room and dormitory were equipped with corner fireplaces.

Also intrinsically geared to the reception of visitors is the

atrium in front of the western end of the Church, and in a

very specific sense: the three porches attached to it in the

west, the south, and the north are where the guests are

formally received, screened, and distributed to their

respective quarters.

"Omnes superuenientes hospites tamquam Christus suscipiantur, quia

ipse dicturus est: Hospis fui et suscepistis me." Benedicti Regula, chap. 53,

ed. Hanslik, 1960, 123; McCann, 1952, 118; Steidel, 1952, 257. The

prototypical biblical hospitality is that which Abraham extended to the

Trinity in Genesis XVIII which as Charles W. Jones reminds me, had

a lasting effect on the Palestinian hosts Jerome, Rufinus and others and

through them on the West.

"Et omnibus congruus honor exhibeatur, maxime domesticis fidei et

peregrinis", ed. Hanslik, loc. cit; McCann, loc. cit.; Steidel, loc. cit.

"Pauperum et peregrinorum maxime susceptioni cura sollicite exhibeatur,

quia in ipsis magis Christus suscipitur; nam diuitum terror ipse sibi exigit

honorum" (ibid.). ed. Hanslik, op. cit., 124; McCann, op. cit., 120;

Steidle, op. cit., 258.

"Coquina abbatis et hospitum super se sit, ut incertis horis superuenientes

hospites, qui numquam desunt monasterio, non inquietentur fratres"

(ibid.).

Capitulare missorum generale, 802, chap. 5, Mon. Germ., Legum II,

Capit. I, ed. Boretius, 1883, 93: "Ut sanctis ecclesiis Dei neque viduis

neque orphanis neque peregrinis fraude vel rapinam vel aliquit iniuriae quis

facere presumat: quia ipse domnus imperator, post Domini et sanctis eius,

eorum et protector et defensor esse constitutus est." Cf. Ganshof, 1963, 64,

74, 96. The case for the poor is re-emphasized in a special capitulary of

the same year, see Boretius, op. cit., 99-102, and Eckhardt, 1956. For a

complete English translation of the general capitulary of 802 see "Selections

from the Laws of Charles the Great," ed. Munro, 1900, 16-33.

V.8.2

LODGING FOR VISITING MONKS

The synod of 817 prescribed that each monastery should be

provided with special quarters for the reception of the

visiting monks: "Ut dormitorium iuxta oratorium constituatur

ubi superuenientes monachi dormiant."[284]

Hildemar, in

his commentary on the Rule of St. Benedict (written between

845 and 850 at the monastery of Civate in Italy),

furnishes us with some further detail on this subject.[285]

The

brothers, he tells us, should never be quartered with any

laymen (not even with the vassalli by whom they may be

accompanied) as the latter often stay awake until midnight,

passing their time in idle talking and jesting, while the

monks should spend it in silence and prayer.[286]

For this

reason their Dormitory should be next to the church, so

that they can enter the sanctuary at any time of the day and

night.[287]

In compliance with these stipulations a Lodging for

Visiting Monks is established on the Plan of St. Gall, in the

corner between the northern transept arm and the northern

aisle of the Church (fig. 391). It consists of a long and narrow

apartment, 10 feet wide and 50 feet long, which is internally

divided into a living room (susceptio fr̄m̄ supuenientium) and

a dormitory (dormitoriū eorum), both of equal dimensions. The

living room is furnished with two wall benches and from

it direct access is gained to the Church through a door

which leads into the northern transept arm. The dormitory

has a privy attached to it (necessarium); and the number of

beds that it contains suggests that the maximum number of

daily visitors who could be expected from other convents

was six.

PLAN OF ST. GALL

392.

391.X

HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS

Installation of auxiliary services in annexes to

the main houses characterizes all facilities of

the Plan of St. Gall associated with potential

fire hazards: the tasks of baking, brewing,

cooking, blacksmithing, and goldsmithing (figs

292, 396, 419-421, and 462, below).

The narrow shape of the Lodging for Visiting Monks—

like that of the Lodging of the Master of the Outer School,

which lies next to it, and that of the Porter's Lodging which

follows—suggests that all of these apartments are installed

in a narrow lean-to, built against the northern aisle of the

Church (figs. 108, 112 and 191).

The visiting monks take their meal in the Refectory for

the regular monks, where a table for guests is set aside for

that special purpose.[288]

If one among the visiting brothers

decides to stay longer, or is a familiaris, Hildemar tell us,

he will join into the life of the regular monks, sleep and eat

with them, read in the claustrum, and attend the chapter

meetings in the morning and evening.[289]

The Lodging for

Visiting Monks may also on occasion have been used by

one or the other of the regular monks when, after a long

absence, he returned from a journey or from some other

task that took him away from the mother house.[290]

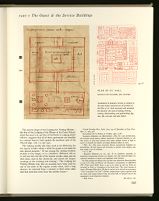

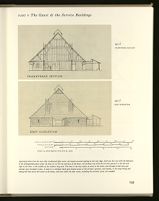

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS

393.B LONGITUDINAL SECTION

The presumption in these reconstructions is

that the roof was supported by a frame of

freestanding inner posts connected lengthwise

by roof plates and crosswise by tie beams

(cf. fig. 393.D). The rafters rise in two tiers,

the lower from wall plates to roof plate, the

upper, at a slightly steeper angle, from the

roof plates to the ridge.

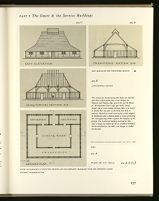

393.A PLAN

For historical justification of the

reconstructions shown in this series of

illustrations we refer to pages 72-82 above,

where it has been shown that the guest and

service buildings of the Plan of St. Gall

belong to a vernacular building tradition

traceable in the Germanic territories of the

Lowlands to the 14th century B.C. The

traditional material for this building type

was timber.

All the guest and service buildings of the Plan

were freestanding; in reconstructing

their plans and elevations, we have used the

simple lines of the Plan as indicating their

interior dimensions. The elevations shown

here are purely conjectural but based on the

assumption of comfortable minimum heights

required by the functions of each component

of the building. Carpentry details derive

from later medieval buildings (see above,

pages 88ff).

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS

393.C EAST ELEVATION

The roof lines might have been straight. We

have chosen to show them broken, because

they thus reflect more clearly in the exterior

appearance of the building the composition

and boundary lines of its inner spaces. To

hip the roof over the narrow ends of the

building is a sound constructional assumption,

since it steadies the roof in the longitudinal

orientation and is a feature archaeologically

well attested as early as the Iron Age.

393.D TRANSVERSE SECTION

393.E NORTH ELEVATION

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

PLAN OF ST. GALL. LODGING OF THE MASTER OF THE HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS & PAUPERS

394.A

394.B

The nature of his duties required that the caretaker of the poor have his own lodging, a

simple rectangular room with corner fireplace installed as a lean-to abutting the south aisle

of the church and about 15 feet from the Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers. The porch

through which pilgrims and paupers entered was an access to be shared by them with the

monastery's workmen and tradesmen, and by other lay visitors such as relatives of the

brothers, who might enter through that porch and then converse with their kin in the Monks'

Parlor next to and east of the Hospice. No outsider went beyond this Parlor without

escort.

The Master of the Hospice was assisted by servants lodged in the eastern aisle of the

Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers. The suggested circulation patterns show with what

relative ease the congress of the monastery with the world might be controlled. Confined on

the east by the Cellar wall and on the south by a (presumptive) fence, travelers could

enter the areas around the Hospice, dine in the house provided for their needs, rest,

exchange news and gossip of the day, and move on, all without disturbing the more orderly

life going forward in the calm heart of the monastery.

1. Church- Ig. Porch of Reception- WP western paradise- I1. Tower of St. Gabriel- Ih.

Porch to Hospice- Ii. Lodging, Master of Hospice for Pilgrims & Paupers- 31. Hospice

for Pilgrims & Paupers- 32. Kitchen, Bake & Brewhouse for Pilgrims & Paupers.

Expositio Hildemari, ed. Mittermüller, 1880, 611: quia dormitorium,

ubi monachi suscipi debent, habetur separatum a laicorum cubiculo, i.e. ubi

laici jacent, eo quod laici possunt stare usque mediam noctem et loqui et

jocari, et monachi non debent, sed magis silentium habere et orare.

Ibid., 612: Ideo juxta oratorium illorum monachorum hospitum est

dormitorium, ubi ipsi jaceant soli reverenter, et possint nocte surgere, qua

hora velint, et ire in ecclesiam.

Expositio Hildemari, ed. cit., 582: Si est familiaris monachus, in

dormitorio monachorum dormit et in claustra cum aliis monachis legit et in

refectorio manducat et mane et ad capitulum venit fratrum.

On Irish monks and abbots who, on their way back from Rome decided

to stay in St. Gall, see Meyer von Knonau's commentary on Ekkeharti

(IV). Casus sancti Galli, chap. 2, pp. 9-10, notes 33 and 34. They are

recorded as Scotti or Scotigenae in the death lists. The most famous of

these is Moengal-Marcellus, (Notker's teacher) who visited the monastery

"of his compatriot St. Gall" (Gallum compatriotam suum) together with

his uncle, and stayed behind when the latter left, to become one of the

monastery's most illustrious teachers.

V.8.3

HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS

THE MAIN HOUSE

The Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers (fig. 392) lies to

the south of the Church and west of the cloister in a yard

that is bounded to the east by the Monks' Cellar and Larder,

to the south and west by fences that separate the pilgrims

and paupers from the houses for the livestock and their

keepers, and to the north by the semicircular atrium of the

Church. Access to this yard is gained by a porch built

against the southern wall of the atrium, which also serves

as entrance for the monastery's servants. The house is

identified by the hexameter, "Here let the throng of pilgrims

find friendly reception" (hic peregrinorum la&etur

turba recepta).

The Hospice is composed of a main house for the reception

of the pilgrims and paupers, and an annex containing

kitchen, bakery, and brewing facilities. The main house

measures 50 by 60 feet. It has in its center a large rectangular

room that is designated as "living room" or "hall for

the pilgrims and paupers" (domus peregrinorum et pauperėm).

This space must also have served as dining room, as may

be gathered from the benches that run all around its circumference.

The draftsman did not enter the tables, but

the meaning of this seating arrangement is clear from the

corresponding space in the House for Distinguished Guests.

The house receives its warmth from a large central fireplace,

and the smoke escapes through a louver (testu) in the roof

above it.[291]

Two rooms on the front side of the house are

used as quarters for the servants (seruientium mansiones),

two corresponding rooms at the rear as "supply room"

(camera) and "cellar" (cellarium). The spaces under the

lean-to's on the narrow sides of the house serve as dormitories

for the pilgrims and paupers (dormitorium and

aliud). The Statutes of Adalhard, written at about the same

time (822) that the Plan of St. Gall was drawn, make it

clear that the normal number of pilgrims expected to spend

the night in the monastery of Corbie was twelve[292]

—this

corresponds quite closely to the number of pilgrims who

could be housed in the rooms which in the Plan of St. Gall

are designated as dormitories for pilgrims. They are capable

of accommodating eight beds each, ranging in a single row

all around the walls of the room. But, in an emergency, of

course, the bedding capacity of the Hospice for the paupers

could be increased by a wide margin, if the benches in the

hall were used as additional facilities for sleeping.

The Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers is wanting of that

other convenience so profusely attached to the houses that

shelter the upper social strata of the monastic community:

the privy. I have already had occasion to remark that I do

not think that this is an oversight.[293]

PLAN OF ST. GALL. LODGING OF THE PORTER

395.A

395.B

The Porter's Lodging, with its corner fireplace, private privy, quarters for as many as five

assistants, and garden, reflects the importance of this official in monastic life; his quarters

were nearly twice the size of those of the Master of the Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers, his

subordinate. St. Benedict stipulated that the Porter be selected with special care, for he was

charged with the reception of all guests and the distribution of food and services to fill all

their needs. His role was diplomat and administrator.

In particular his duties were to identify and greet distinguished guests of the monastery and

their retinues, and then see to their escort through the north reception porch into the grounds

and quarters provided for them in the House for Distinguished Guests and its Annex.

Guests of high social standing might have business with the internal life of the monastery,

but their reception area, though larger and better appointed than that for pilgrims and

paupers, was likewise closed off from any direct access to the inner monastery grounds;

similarly, unnecessary contact of such guests with the less exalted class of traveler lodged

upon the south was by these arrangements largely precluded.

1. Church- Ie. Lodging of the Porter- If. Porch of the Porter- Ig. Porch of Reception-Ik.

Tower of St Michael- 10. Kitchen, Bake & Brewhouse for Distinguished Guests- K.

Kitchen- L. Larder- B. Bakery- BH Brewery- 11. House for Distinguished Guests- DH

Dining Hall.

We have reconstructed the Hospice for Pilgrims and

Paupers as a large rectangular hall with central hearth and

louver in the roof above it, the hall being surrounded on

all four sides by aisles or lean-to's (fig. 393A-E). In view

of the constructional characteristics of the genus of houses

to which the guest and service buildings of the Plan of St.

Gall historically belong, it is reasonable to assume that the

roof of this, as well as of all other related houses of the Plan,

is carried by a frame of timber, consisting of two rows of

posts connected crosswise by tie beams and lengthwise by

post plates. The natural and historical place for alignment

for these two rows of posts are the lines that define the

boundaries between the aisles and the central hall of the

house. Since the Plan does not designate the location of the

structural members in this type of house, but confines

itself merely to delineating the boundaries of its component

spaces, we know nothing about the respective distances of

the roof-supporting posts. Ours are purely conjectural.

There is a variety of other possibilities.

As there is only one source of heat for both the hall and

the peripheral spaces, the latter can only have been partially

boarded off against the center hall. The separating wall

paneling may not have risen much higher than the backrest

of the benches that surround the hall. We have reconstructed

the roof as a simple rafter roof (of the type exemplified

by St. Mary's Hospital in Chichester, figs. 341-343), but

the roof might have belonged as well to the family of purlin

roofs.

We are well informed about the function and management

of the Hospice for Paupers through the Administrative

Directives of Adalhard of Corbie.[294]

The management

of the Hospice for Paupers, we learn from this account, was

in the hands of the Hosteler (hostellarius) who was subject

to the directives of the Porter (portarius). On the Plan of

St. Gall the Hosteler is accommodated in a special apartment

which abuts the southern aisle of the church immediately

to the side of the Hospice for Paupers. The rooms

that are designated camera and cellarium in the Hospice for

Paupers are the Hosteler's food and supply rooms.

Adalhard orders that each pilgrim was to receive, each

day, a loaf of bread, weighing 3½ pounds and made of a

mixture of wheat and rye, and that on his departure he was

to be issued half a loaf of the same kind for his journey.

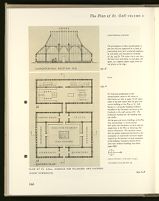

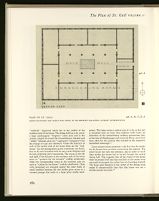

396. PLAN OF ST. GALL

HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS, WITH ANNEX CONTAINING KITCHEN, BAKE & BREWING FACILITIES

The layout of this structure is in its basic dispositions the same as the Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers. It also consists of a main house with

an annex to accommodate services involving fire hazards. Likewise the main house here consists of a central hall for dining and a subsidiary

suite of outer rooms used for sleeping, the accommodation of servants, and when appropriate, even horses. But the layout of the House for

Distinguished Guests is more explicit than its humbler counterpart. Here with great precision is portrayed placement of tables and benches in

the center hall, as well as the furnishings in bedrooms of the Distinguished Guests. These rooms are provided with corner fireplaces, making

their comfort independent of the open fireplace in the middle of the center hall, and thus affording their occupants the luxury of privacy. The

presence of these corner fireplaces induced us to assume that the outer walls of this house were intended to be of masonry.

The use of masonry and timber in a royal Carolingian hall is well attested through an important literary source, the Brevium Exempla

(p. 36ff, above), where the DOMUS REGALIS of an unnamed estate near Annapes is described as being constructed in timber "in the usual

fashion." This remark reveals that wood was the more common and traditional material for this house type. Hipped roofs are attested for the

windswept continental coastlands of the North Sea from the 7th century B.C. onward (figs. 295-297 and 314, above) and became a permanent

trait of rural architecture north of the Alps (figs. 335-336, above).

Windows are not part of the customary design of this house type. They became an indispensable adjunct when its outer rooms were partitioned,

separating them from the only other traditional light source: the lantern-covered opening in the roof ridge. Such was the case with the bedrooms

of the distinguished guests under the lean-to's of the two end bays of the house, and perhaps even with the servants quarters to the left and

right of the door, in the middle of the southern long wall. This door is the only means of access to the house, and through it both men and

animals were intended to pass. It leads to a vestibule which gives lateral access to the servants' quarters, and axially, to the large living and

dining hall that forms the center of the house, and from which all other rooms, including the servants' privy, are reached.

PLAN OF ST. GALL

397.B LONGITUDINAL SECTION

397.A PLAN

HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

PLAN OF ST. GALL

397.C SOUTH ELEVATION

397.D NORTH ELEVATION

HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

397.E TRANSVERSE SECTION

397.F EAST ELEVATION

398. PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

AUTHORS' RECONSTRUCTION

This perspective shows the large center nave of the house, the communal living and dining area, and bedrooms of servants to the left, with

stables to the right. Tables and benches ranged around the walls of the center space presumably could be rearranged to meet particular needs of a

group of guests, or moved back altogether when not in use.

In each building of the Plan housing both animals and men, the layout is similar: servants' quarters flank (or guard) the entrance while

animals pass through the common room to the rear. This disposition may reflect a defensive posture of ancient antecedents. In the House for

Distinguished Guests it had the further convenience of proximity to the privy where, as an amenity afforded guests of high rank, refuse and

manure from the stables might be readily disposed of.

Carpentry details shown here derive from later medieval examples (cf. page 115ff, above); but the concept of a timber-framed roof dividing

the house into nave, aisles, and bays, is clearly in the historical tradition of the Germanic all-purpose house to which the preceding chapters

have been devoted.

This exterior view shows, in the left foreground of the main house, the privy for servants and guards. In the right background lies the annex

containing kitchen, baking, and brewing facilities. Bedrooms for distinguished guests, with individual corner fireplaces and private toilets, are

under the hips of the roof on the two narrow sides of the house. Stables are in the northern aisle parallel to the servants' privy. Bedrooms of

the latter are on the entrance side (not visible here).

399. ST. GALL

HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS; ALSO ITS KITCHEN, BAKE, AND BREW HOUSE

issued a quarter loaf of bread per head.

The daily ration in the Hospice also included two tankards

of beer, but whether or not any wine could be served

was left to the judgment of the prior. Special consideration

was to be given to the sick pilgrims, and to those who came

from distant lands, for whom the Hosteller could draw

additional rations "so that he should not incur any shortages

in his normal allotments." Provisions not spent on the

days when the number of visitors fell below the expected

norm were to be saved and used as a surplus to be drawn

against on days when the norm was exceeded.

Adalhard specifies the source and volume of beans, lard,

and cheese, as well as the amount of eel and meat, and all

of the other indispensible items, not omitting the "old

clothes and shoes of the monks, which the Hosteler receives

from the Chamberlain for distribution to the paupers

as is customary." He lists the amount of money that should

be distributed among the poor, pointing out that no rigidly

binding rules could be established in this delicate matter

where varying needs require varying action, and he terminates

this chapter of his statute with the wistful admonition:

"We therefore beseech all those upon whom this office will

be bestowed in our monastery that, in their generosity and

distribution, they bow to the will of God rather than to their

own parsimoniousness, since everyone is to be rewarded

according to the pattern he has set for himself."[295]

With regard to the meaning of this term, cf. above pp. 117ff. Keller's

(1844, 27) and Willis' (1848, 108-9) assertion that the Hospice of the

Paupers is devoid of a fireplace and a dining room is based on an untenable

interpretation of the square in the center of this house, designated

with the word testu, as a "garden hut," and on a misunderstanding of

the term domus, which does not refer to the whole of the house but

only to the common hall for the pilgrims and paupers in the center of

the house. Cf. above pp. 77-78.

Consuetudines Corbeienses, chap. 2, ed. Semmler, in Corp. Cons.

Mon., I, 1963, 372: duodecim pauperes qui supra noctem ibi manent.

THE KITCHEN, BAKE AND BREW HOUSE FOR

PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS

The Kitchen, Bake and Brew House for Pilgrims and

Paupers lies ten feet west of the Hospice, and covers a

surface area of 22½ feet by 60 feet. Its layout repeats on a

400. PLAN OF ST. GALL

KITCHEN, BAKE AND BREWHOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS. AUTHORS' RECONSTRUCTION OF

ROOF FRAMING, WITH SOME TIMBERS REMOVED

A widened aisle forms an extended lean-to accommodating kitchen and larder on either side of the entrance. The wall plate for the main space

of the house provides footing for rafters over this enlarged lean-to. In the nave space are the oven, kneading troughs, and tables for shaping

loaves. At right are the brewing range and four tubs or cauldrons for steeping brew. The narrow aisle beyond and to the rear (its interior not

visible here) is of conventional width in relation to the main space, and houses at one end containers for cooling beer and at the other, troughs

for leavening dough.

Monks, which shall be discussed later on. But it combines

with the facilities for brewing (bracitoriū) and baking

(pistrinū) a stove for cooking. This is the meaning that must

be attributed to the square in the bakery immediately in

front of the baking oven (fornax), which is internally divided

into four more squares by two lines crossing each other at

right angles. The same symbol is used for the stove in the

Kitchen for the Distinguished Guests.[296] There, in the

center, of a room, explicitly defined as "kitchen" (culina),

its meaning is unequivocal. The facilities for cooling the

beer (ad refrigerandū ceruisā) and for leavening the bread

(locus conspergendi) are installed in the aisle that runs along

the western side of the house. The equipment is identical

with that of the Bake and Brew House of the Monks, and

the design and construction of the house must also have

been very similar.

See below, p. 165. Keller (1844, 27) and Willis (1848, 108-9)

overlooked this fact and based upon this `oversight' the erroneous conclusion

that the Hospice was not furnished with a kitchen.

Charles W. Jones reminds me, in this context, of a passage in the

Directives of Abbot Adalhard of Corbie containing a strong hint that at

Corbie too, the poor had their own kitchen: "According to custom the

porter should provide firewood for the poor, or other things which are not

recorded here, such as the kettle or dishes or other things that are in their

quarters". See III, 106, and Consuetudines Corbeienses, ed. Semmler,

Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963, 374.

V.8.4

LODGING OF THE MASTER OF THE

HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS

The management of the Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers

was the responsibility of a monastic official to whom the

Plan of St. Gall refers as "the caretaker of the poor" (procurator

pauperum).[297]

His lodging (pausatio procuratoris

pauperum) lies immediately to the north of the Hospice for

Pilgrims and Paupers, between the south porch of the

atrium and the Monks' Parlor (fig. 394). It is an oblong

chamber, 10 feet wide and 25 feet long, which is built

against the southern aisle of the Church, doubtless in the

form of a lean-to. It is provided with a corner fireplace and

doors that connect it with both the court and the southern

aisle of the Church. The Master of the Hospice for Pilgrims

and Paupers is a subordinate of the Porter.

The word procurator has faded so severely that it is barely legible.

In the Administrative Directives of Abbot Adalhard of Corbie the same

official is referred to as hospitalarius. See Consuetudines Corbeienses, ed.

cit., 372.

V.8.5

LODGING FOR THE PORTER

At the gate of the monastery let there be placed a wise old man who

understands how to give and receive a message, and whose years

will keep him from leaving his post. This porter should have a room

near the gate, so that those who come may always find someone to

answer them. As soon as anyone knocks, or a poor man hails him,

let him answer Deo gratias or Benedic. Then let him attend to them

promptly, with all the gentleness of the fear of God and with fervent

charity. If the porter needs help, let him have one of the younger

brethren.[298]

The Porter was in charge not only of the reception of the

monastery's guests, but also of providing them with food

and bedding. In order to acquit himself of this obligation,

he was assigned one-tenth of the revenues and produce

from the monastery's outlying estates, as well as one-tenth

of the offerings and gifts received at the gate.[299]

He was in

charge of the collection and transportation of his supplies.

At Corbie, for these multiple tasks he was provided with a

staff of ten assistants (prouendarii).[300]

Originally, according

to Hildemar, the duties of the porter were performed by

the monks who were in charge of the abbot's kitchen.[301]

In

Hildemar's own days this was no longer possible because

of the throng of the guests, which required that two brothers

devote themselves exclusively to the task of receiving the

poor and announcing distinguished guests to the abbot or

prior. While one of the porters attended the divine services

or took his meal, the other tended the gate where visitors

might arrive at any time.[302]

Monastic protocol required that

upon entry kings, bishops, and abbots were received by

prostration, the queen by a bend of the knee, others by a

nod of the head.[303]

After the guests had been received and

greeted, they were led to prayer; then they were given the

kiss of peace, and finally, the abbot presented them with

water for their hands, and both the abbot and the community

washed the feet of the guests.[304]

On the Plan of St. Gall, as St. Benedict had stipulated,

the Porter's dwelling lies near the gate of the abbey, next

to the House for Distinguished Guests, and contiguous to

the Porch through which the distinguished visitors enter

(fig. 395). It consists of a long, narrow apartment that is

built against the northern aisle of the Church, forming a

counterpart to the Lodging of the Master of the House for

Pilgrims and Paupers, but it is twice as large as the latter's

dwelling. Internally, it is subdivided into a living room with

corner fireplace (caminata portarii) and a dormitory (cubilium

eius) with six beds and a projecting privy. One door of

the living room opens directly into the northern aisle of the

Church, the other onto a long, narrow yard that borders on

the yard of the House for Distinguished Guests.

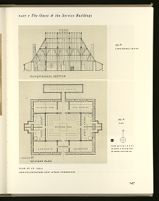

401.A, B, C, D PLAN OF ST. GALL

KITCHEN, BAKE AND BREW HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

The layout of this structure is a striking example of the extraordinary functional flexibility of the building type to which it historically belongs.

The drafters of the Plan found themselves faced with having to enlarge facilities for baking and brewing, installed in the nave of this building,

with a large kitchen and larder. They accomplished this by increasing the width of one of the two aisles of the structure (usually about half that

of the nave) to a ground area equalling the nave, and by accommodating larder and kitchen in this enlarged aisle to either side of an entrance

corridor directly into it. The aisle at the back of the house, used for leavening dough and cooling beer, retained its traditional width.

Benedicti Regula, chap. 66, ed. Hanslik, 1960, 155-57; McCann,

1952, 152-53; Steidle, 1952, 320-21.

Benedicti Regula, chap. 53, ed. Hanslik, 1960, 123-26; McCann,

1952, 118-22; Steidle, 1952, 257-60.

V.8.6

HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

THE KING'S CLAIM ON MONASTIC HOSPITALITY

To the north of the Church in a large enclosure, which

forms the counterpart to the court of the Hospice for

Pilgrims and Paupers, is a house whose elaborate layout

reveals it to be a guesthouse for visitors of unusual stature.

It is here that the traveling emperor or king was received,

his court or his agents (missi), and also, perhaps, the visiting

bishops and abbots.

The king's right to draw on the hospitality of the monasteries

for food and quarters while traveling dates back to

the early days of the introduction of monastic life in transalpine

Europe. But the use that the rulers made of it in the

time of the Carolingians was considerably more burdensome

than it had been under the Merovingians.[305]

Ever-changing

political necessities, the protection of the boundaries, the

maintenance of peace in the interior, prevented the emperor

from establishing a permanent residence. "Performing his

high craft by constantly shifting around,"[306]

he moved from

one of his royal estates to the other—making full use of the

obligations of the abbots and bishops to provide him with

lodging—according to the circumstances that his itinerary

imposed upon him, or simply in response to the necessity

of finding additional subsistance for himself and his court.

The primary motivations for such visits were not always of

an economic or military nature. Gauert's analysis of

Charlemagne's itinerary has shown that the emperor's general

travel schedule often had embedded in it a special

"Gebetsitinerar," at times involving lengthy detours for

visits to religious places where the emperor went primarily

for the purpose of prayer, to participate in important religious

festivals, or to venerate the local saints.[307]

The heaviness

of the economic obligations that a monastery took upon

itself on such occasions depended on the frequency of the

visits, the length of the emperor's stay, and the size of his

retinue. Charlemagne and Louis the Pious availed themselves

of monastic hospitality with discretion; under the

later Carolingian kings the burden became heavier.[308]

But

even as early as the second decade of the ninth century the

sum of monastic obligations in hospitality had reached proportions

so heavy as to drive the witty abbot Theodulf,

Bishop of Orléans, to remark desperately that had St.

Benedict known how many would come, "he would have

locked the doors before them."[309]

To use a phrase coined by Schulte, 1935, 132. For the ambulatory

life of medieval kings in general, see Peyer, 1964.

For more details cf. Lesne's informative chapter on monastic

hospitality extended to kings and their representatives, (Lesne, II,

1922, 287ff.) and Voigt's remarks on the increasingly intolerable economic

burden royal visits imposed upon the abbeys, bishoprics and counties

under the reign of Charles the Bald and Louis the German (Voigt,

1965, 27ff). When Louis the German invaded the empire of the West-Franks

in 858, the bishops, in a petition drafted by Hincmar of Reims,

beseeched the emperor to bolster his economic capabilities through

more efficient management of the crown estates, rather than by depleting

the resources of the abbots, bishops and counts for the sustenance of his

traveling court. They made a plea that their contribution to the maintenance

of the emperor's train be reduced to the share customary during

the reign of his father, Louis the Pious. (Epistola synodi Cariasiacensis

ad Hludowicum regem Germaniae directa, chap. 14, ed. Krause, Mon.

Germ. Hist. Legum Sec. II, Capit. Reg. Franc., II, Hannover, 1897,

437). In a subsequent letter written to Charles the Bald, Hincmar informed

the latter that the substance of his petition to Louis the German

was, in an even more urgent sense, addressed to him (ibid., 428).

Expositio Hildemari, ed. Mittermüller, 1880, 501: "Per Deum, si

nunc adesset S. Benedictus, claudere illis ostium fecisset".

THEIR MAGNITUDE: A REFLECTION OF THE CLOSE

ALLIANCE OF CHURCH AND STATE

The Plan of St. Gall provides for four separate houses

for the reception of royal visitors: 1, a house for the emperor

and his immediate entourage; 2, an ancillary building

containing the kitchen, bake, and brewing facilities pertaining

to this house; 3, a House for Visiting Servants; and,

if my interpretation is correct, 4, a house for the emperor's

vassals and others of knightly rank traveling in the emperor's

train. Plans, sections, reconstructions, and authors'

interpretations for these facilities are shown in figures

396-406.

The total surface area taken up by these houses and their

surrounding courts amounted to 1,360 square feet, or a

little over one-fifth of the surface area of the entire monastery

complex.

The presence of obligatory royal quarters of such magnitude

within the precincts of the monastery is a reflection of

the close alliance that had been struck in the kingdom of the

Franks between the concepts of regnum and sacerdotium, a

development that started with the sanctioning of the Carolingian

house by Pope Zacharias in 751 and reached its

apex with the coronation of Charlemagne in the year 800.

As the appointed successor of the emperors of Rome,

Charlemagne had taken upon himself not only the duty of

protecting the Church in a physical sense, but also the

obligation of safe-guarding its institutions, regulating the

life and education of the clergy, and even ruling in questions

of liturgy and dogma.[310]

It is fully understandable that

within the context of a political philosophy so replete with

religious overtones the emperor's presence in the monastery

was as yet not considered a worldly infraction on

monastic peace and seclusion.

On this aspect of the emperor's responsibilities, see A. Schmidt,

1956, 348; Ganshof, 1960, 96 and Ganshof, 1962, 92.

THE MAIN HOUSE

Layout and function

The general purpose of the House for Distinguished

Guests is defined by a hexameter which reads:

domus

Haec quoque hospitibus parta est quoque suspicientis[311]

This building, too, serves for the reception of guests

The conjunction quoque suggests that the building holds a

position of secondary importance with regard to another

facility for guests, which can only be the Hospice for Pilgrims

and Paupers. The modest slant of this verse is obviously

a reflection of the warning given by St. Benedict

that the hospitality accorded to the poor lies on a higher

plane of religious devotion than that extended to the rich.[312]

But the profuse attention lavished on the internal layout of

the House for Distinguished Guests tends to defy this

thought.

The House is 67½ feet long and 55 feet wide. It has as its

principal room a large rectangular hall, which its explanatory

title defines as the "dining hall of the guests" (domus

hospitū ad prandendum). Access to this is gained through a

402. PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR SERVANTS OF OUTLYING ESTATES AND FOR SERVANTS

TRAVELING WITH THE EMPEROR'S COURT (NOT CERTAIN: cf. BUILDING 34)

The house is one of four identical buildings located to the right of the entrance

road where most of the monastery's livestock is kept. Its large central hall, like

those of many other buildings of this group, is referred to as DOMUS, a term used

by the drafters of the Plan not to designate the entire house (as its classical usage

would prescribe), but as a name for the common living room where men gather

around the open fireplace for conversation and meals. The spaces in the aisles

and under the lean-to's are used for sleeping and for the stabling of livestock.

PLAN OF ST. GALL

403.C

403.D EAST ELEVATION AND TRANSVERSE SECTION

403.B LONGITUDINAL SECTION

The criteria for reconstructing this house are identical

with those which guided that of the Hospice for

Pilgrims and Paupers (figs. 393.A-E) and the House

for Distinguished Guests (figs. 397.A-F). Being

smaller and of more modest purpose, there is no reason

to assume that any part of the house was built in

masonry, beyond (as sound construction would suggest)

its foundation and a shallow plinth of stones protecting

the roof-supporting timbers against the dampness of the

ground. The traditional building material for this

type of house was timber for all its structural members,

wattle-and-daub for the walls, and shingles or shakes

for the roof.

403.A PLAN

HOUSE FOR SERVANTS OF OUTLYING ESTATES AND FOR SERVANTS TRAVELING WITH THE EMPEROR'S COURT

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

404. PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR KNIGHTS AND VASSALS IN THE EMPEROR'S FOLLOWING

Its identification must remain tentative, for the lines and titles of this building were erased in the 12th century by a monk who wrote a Life

of St. Martin on the verso of the Plan, spilling the last 22 lines of text onto the plan of this house. The few fragments of titles that escaped

his knife were obliterated in the 19th century by an attempt to restore them with a chemical substance that left only coarse blotches on the

parchment wherever it was applied.

405. PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR KNIGHTS AND VASSALS IN THE EMPEROR'S FOLLOWING

X-rays revealed the outlines of a colossal variant of the standard house of the Plan, with an entrance in one narrow side. Comparison with

other similar buildings leaves no doubt that the large center room was intended as a common hall for living and dining, with peripheral spaces

serving partly for bedrooms, partly for stables.

406.A PLAN OF ST. GALL

HOUSE FOR KNIGHTS AND VASSALS WHO TRAVEL IN THE EMPEROR'S FOLLOWING. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

southern aisle of the house. The dining hall has in its center

a large quadrangular "fireplace" (locus foci) and in the

corners, ranged all around the circumference, benches and

"tables" (mensae), plus two "cupboards" (toregmata[313] ) for

the storage of cups and tableware. Under the lean-to's at

each of the narrow ends of the house there are the "bedrooms"

for the distinguished guests (caminatae cum lectis),

four in all, each furnished with its own corner fireplace and

its own projecting privy (necessariü). The rooms to the left

and right of the entrance in the southern aisle of the house

serve as "quarters for the servants" (cubilia seruitorum),

while two corresponding rooms in the northern aisle are

used as "stables for the horses" (stabula caballorum). Their

cribs (praesepia) are arranged against the outer walls. A

small vestibule between the two stables gives access to a

covered passage that leads to a large privy (exitus neces-

sarius). The latter covers a surface area of 10 by 45 feet and

is furnished with no fewer than eighteen toilet seats—an

indication of the extraordinary sanitary precautions that,

at the time of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious, must have

been taken for the persons who traveled in the emperor's

immediate entourage.[314]

I have already drawn attention to the fact that the stables

for the horses have no direct access from the exterior. The

entire house has only one entrance, and in order to reach

their stables the horses had to be led through the central

dining hall. This suggests that all the rooms of the house

were on ground level and that the floor of the center room

was made of stamped clay rather than of a boarding of wood.

The large open fireplace in the center of the dining room

makes it unequivocably clear that this house was not a

double-storied structure.[315]

406.B

By making the center hall of this building 45 feet wide by 60 feet long, the drafters of the Plan pushed the structural capabilities of the aisled

Germanic all-purpose house to its limits. Spans of 45 feet, rare even in church construction, were unheard-of in domestic architecture. We

know of only one other medieval building of even comparable dimensions: the barn of the abbey grange of Parçay-Meslay, France (figs. 352-355)

at a width of 80 feet. But the vast roof of that barn is supported, not by the traditional two, but by four rows of freestanding inner posts.

We do not believe that the roof of the House for Knights and Vassals could have been supported successfully by less posting and have therefore

introduced in our reconstruction two additional rows of posts, that reduce the center span of the inner hall from 45 to a more conventional

27 feet.

Incorporating the doubled rows of posting is not in conflict with methods of architectural rendering employed by the drafters of the Plan.

They were not concerned with constructional details, but primarily with establishing the boundaries of each building on the site in terms of its

function and its components. The size of a royal retinue—including its servants, grooms, bodyguard, as well as the principals themselves—

justifies the tentative identification of this house.

In this, as in other buildings of the Plan, details of construction engineering were left to be resolved by the ingenuity of a master builder who

would determine in what ways a building conceived for the purpose of housing up to 40 men and 30 horses, and their attendants, could be

realized as functional architecture. The interaction of planners with builders is elsewhere attested on the Plan, wherever features obviously

intended and needed are absent: staircases, doors and windows, and others (see I. 13, 65ff).

The main point of interest, we believe, in our investigation of this particular building is that the prevailing building type of the Plan of St. Gall,

the three-aisled hall—without loss of the essence of its character—adapts with ease and dignity and possibly with some elegance, to a building of

relatively inordinate size through the device of adding an aisle between the central main space of the nave, and each of the lean-to side aisles.

In effect, a five-aisled hall is thus formed (see fig. 354.A, B, Parçay-Meslay, and Les Halles, Côte St. André, Isère, France).

In writing this line the scribe had started Haec quoque hospitibus . . . ,

but struck out the word quoque and replaced it by domus, when he

discovered that quoque appeared twice in his line. The mistake is interesting,

because it shows how strongly the shaper of this hexameter was

preoccupied with the content attached to the conjunction quoque.

All these features were of primary importance in our analysis of the

building type, cf. above, pp. 82ff and 115ff.

Materials and mode of construction

In contrast to the Abbot's House,[316]

whose typological

roots lie in the South, the House for Distinguished Guests,

as has been demonstrated, is a descendant of a strictly

Northern building type. It may have been built entirely

in wood, or it may have had its circumference walls constructed

in masonry. In our reconstructions (figs. 397-399)

we have chosen this latter solution in order to demonstrate

the possibility of mixed materials on this higher social level

of building. In the interior the roof must have been supported

by two parallel rows of wooden posts, framed into

weight- and thrust-resisting trusses with the aid of tie

beams and post plates. If the roof belonged to the purlin

family of roofs, its basic design cannot have differed greatly

from what we have suggested in figures 397 and 398. For

the thirteenth century this type of roof is well attested, at

least on the Continent, as has been demonstrated by the

examples discussed above on pages 88ff. It may have been

as common in Carolingian times.

That royal timber houses with masonry walls existed in

Carolingian times is known through the Brevium exempla,

for it is doubtlessly to this mixture of materials that the

author of this work refers, when describing the domus

regalis of one of his anonymous crown estates as a house that

was "externally built in stone, and inside all in timber"

(exterius ex lapide et interius ex ligno bene constructam).[317]

PLAN OF ST. GALL

406.C

NORTH ELEVATION

HOUSE FOR KNIGHTS AND VASSALS WHO TRAVEL IN THE EMPEROR'S FOLLOWING

Separation of common & private rooms

The internal layout of the House for Distinguished

Guests (fig. 398) is historically of particular interest, as it

shows that at the beginning of the ninth century the timbered

royal hall was sufficiently partitioned internally to

allow the lord to withdraw from the ranks of his followers

to the privacy of separate bedrooms. Dining was still a

communal function. But the establishment of individual

fireplaces with chimneys in the lord's private chambers

made the latter independent from the open fire in the floor

of the hall. Architecturally speaking, this means that the

private bedrooms under the lean-to's at each end of the

hall could have been screened off from the rest of the

building, not only by vertical wall partitions (as they most

certainly were), but also by their own individual ceilings.

If ceilings were installed, the walls required windows,

since ceilings would have deprived the bedrooms of the

principal source of light for the house—the louver over the

fireplace in the ridge of the roof of the hall. The quarters

of the servants, on the other hand, cannot have been provided

with ceilings, since they depended for warmth on the

heat furnished by the communal fire in the center hall.

Housing capacity

The House for Distinguished Guests can accommodate

eight visitors of rank in four separate rooms, each of which

is furnished with two beds, two benches, and a corner

fireplace.[318]

These are the rooms for the emperor, the empress,

or any other members of the imperial family who

accompanied the emperor on his travels, and some of the

highest ranking ministers and councilors who were part of

the emperor's permanent staff. The rooms for the servants

in the southern aisle of the house have a bedding capacity

for eighteen men. This is the number of beds of standard

size that could be set up for the servants if they were ranged

peripherally along the walls of their rooms (nine in each).

Eighteen also happens to be the number of toilet seats

available in the servant's privy. The two stables in the

northern aisle of the house can accommodate four horses

406.D

TRANSVERSE SECTION

HOUSE FOR KNIGHTS AND VASSALS WHO TRAVEL IN THE EMPEROR'S FOLLOWING

7½ feet long). These must have been the mounts of the distinguished

guests, since their number corresponds exactly

to the number of beds available in the latter's private

chambers.

Even the seating capacity of the dining room is closely

correlated with the total number of men who can be accommodated

in the House for Distinguished Guests. The

eastern or upper end of the hall is furnished with two short

straight tables, each capable of seating four of the eight

distinguished guests (if we attribute to each of them a sitting

area 2½ feet wide). The western or lower end has longer,

L-shaped tables with sufficient sitting space to take care of

the eighteen servants.

Stephani's account of the bedding capacity of the private rooms for

the distinguished guests is wrong ("Jedes Schlafzimmer sieht sechs

Schlafbänke und ein zu wenigstens noch zwei weiteren Personen Raum

bietendes Doppelbett vor, will also zumindest acht Personen Aufnahme

gewähren"); see Stephani, II, 1903, 32-33. The benches on either side

of the corner fireplace are for sitting, not for sleeping. They are too short

to be interpreted as beds.

Number and composition of officers of state

in the emperor's train

There are no conclusive studies on the number or composition

of the officers of state who accompanied the emperor

on his travels.[319]

From Hincmar's account of Adalhard

of Corbie's De Ordine Imperii,[320]

it appears that the central

administrative body of the Carolingian court consisted of a

staff of six leading functionaries, who by the very definition

of their office were part and parcel of the emperor's personal

entourage, viz., the Seneschal (senescalcus, literally,

"the old servant") who was in charge of provisions and

especially those of the royal table; the Butler (buticularius),

406.E PLAN OF ST. GALL

EAST ELEVATION

HOUSE FOR KNIGHTS AND VASSALS WHO TRAVEL IN THE EMPEROR'S FOLLOWING

charge of lodging and the royal treasury; the Constable

(comes stabuli) in charge of horses and all other means of

transportation; the Count Palatine (comes palatinus), the

primary officer in charge of the empire's judiciary administration;

and last but not least, the Arch Chaplain (summus

capellanus), the emperor's primary advisor in ecclesiastical

and educational matters, whose office later became absorbed

in that of the Chancellor (summus sacri palatii cancellarius).[321]

Readiness for action involving the state and the imperial

household in its entirety would have required the presence

of all these men. But it is well known that the holders of

these offices were often away from the court in the summer

on special missions.[322] The House for Distinguished Guests,

nevertheless, would have been equipped to accommodate

all these men besides the emperor himself, plus his wife or

one of his children. How many members of his family he

was wont to have with him when traveling is another

question for which we have no ready answer. "Charlemagne,"

we are told by Einhard, "cared so deeply for the

training of his children that he never took his meal without

them when he was at home, and never made a journey

without them."[323] Although this could scarcely have applied

to all the seven sons and daughters[324] that Einhard ascribes

to Charlemagne, it would still suggest that the traveling

emperor was frequently accompanied by one or another of

his sons and daughters.[325] When Louis the Pious stayed in

St. Gall in 857, his sons Karlmann and Karl III were with

him.[326] This is about all that seems to be known on this

subject.

The Plan of St. Gall may actually help us here to close a

gap of knowledge. It discloses that at the time of Louis the

Pious a monastery was expected to be capable of taking care

of a royal party consisting of eight dignitaries of state or

members of the imperial family, their mounts, and eighteen

of their personal servants. In later centuries the figure may

have been considerably larger. The Consuetudinary of

Farfa—in reality the customs of Cluny (written between

house for forty male and thirty female members of the

emperor's train, plus a stable capable of sheltering some

150 horses.[327] Yet conditions at Cluny were probably

unusual. A fulcrum of revival and reform among the

monasteries of France and unbelievably rich, the abbey

was already well on its way toward wedging itself as an

arbitrating spiritual force into the interplay between the

secular and the ecclesiastical powers of the period.

A systematical study of the signatures attached to imperial deeds,

issued as the emperor moved from place to place, may help to clarify

this problem.

Cf. Ganshof's remarks on the "aulic" nature of this staff of officers

and their respective duties, Ganshof, 1958, 47-48; 1962, 99-100; 1965,

361ff. On the ambivalence of the offices of the summus capellanus and

summus cancellarius, see Klewitz, 1937, 52-55.

For a recent study on the court of Charlemagne and its fluctuating

composition, see Fleckenstein, 1965.

Einhard's Life of Charlemagne, ed. Garrod and Mowat, 1915,

23-25; Éginhard, Vie de Charlemagne, ed. Halphen, 1923, 60-61; The

Life of Charlemagne by Einhard, ed. Painter, 1960, 48. The phrase is

fashioned after a passage in Suetonius' Life of the Emperor Augustus.

On the veracity of Einhard's testimony even where it is couched

in literary imagery borrowed from Suetonius, see Beumann, 1951,

1962; and Fleckenstein, 1965, 24ff.

Notkeri Gesta Karoli, Book I, chap. 34, ed. Rau, in Quellen zur

Karolingischen Reichsgeschichte, III, 1960, 374-75.

Consuetudines Farfenses, Book II, chap. 1, ed. Albers, in Cons. Mon.,

I, 1900, 138. Cf. below, pp. 277, 306. The stable for the horses was

280 feet long and 25 feet wide. Counting a standing area of 5 by 7½ feet

per horse, this house would shelter 152 horses stabled in opposite rows

along the two long walls of the structure. From this figure, of course,

one would have to subtract a certain number, as some of the space in the

walls must have been taken up by entrances. The second story of this

stable house contained the eating and sleeping quarters of the riding

members of the emperor's train, who could not be accommodated in the

house of the noblemen and their ladies. In addition to the mounted

following there was also a train of unmounted men.

Other supporting forces

Even in the ninth century, nevertheless, a guest house

with a bedding capacity of eight distinguished guests, their

horses, and eighteen of their servants, is not likely to have

been capable of accommodating the whole of the emperor's

permanent train. To be protected, the king needed a bodyguard.

Such a guard of mounted knights would not necessarily

have had to be very large, yet it is unlikely to have

consisted of fewer than twenty or thirty men. They, too, and

their horses would have to be provided with quarters. One

would have to expect, additionally, a small train of wagons

with emergency rations, kitchens, tents, and other equipment

indispensable to the movement of the court. This

involved another troup of servants who would also have to

be sheltered. The Plan of St. Gall shows two buildings that

may have performed that function, located at the gate of the

monastery in the immediate vicinity of the House for Distinguished

Guests. But before we turn to them, some attention

must be paid to the kitchen, bake, and brewing facilities

of the House for Distinguished Guests.

KITCHEN, BAKE AND BREW HOUSE FOR

THE DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

The main portion of this structure, which covers an area

roughly 50 by 55 feet (figs. 396, 400-401), is identical

with that of the Bake and Brew House for Pilgrims and

Paupers (fig. 392). But its outside appearance must have

been quite different, as it had attached to it on the side facing

the House for Distinguished Guests, two large rectangular

rooms (17½ feet by 22½ feet); one of which served as the

guests' kitchen (culina hospitū), the other as "larder"

(promptuariū). The kitchen stove, a square of 5 by 5 feet, is

subdivided into four cooking areas by two median lines that

bisect it at right angles. The principal space of the house,

measuring 20 by 55 feet, contains in its southern half the

"bakery" (pistrinum) with its "oven" (fornax), two kneading

troughs (not designated as such by inscriptions), and

all around the periphery of the room, the indispensable

tables for the shaping and laying out of the loaves. The

northern half contains the brew house (domus conficiendae

celiae) with fires and coppers for malting the grain (fig.

401A). The aisle in the rear of the house is subdivided into

two equal parts, each serving as an accessory to the work

carried on in the corresponding portion of the principal

space of the house. The room near the bakery is designated

as "the place where dough is made [by mingling flour with

water]" (interndae pastae locus) and for that purpose it is

furnished with a long trough and a circular vat. The other

near the brewery, is described as the place where the brew is

"cooled" (hic refrigeratur ceruisa). It is equipped with two

smaller troughs that stand on either side of a circular vat.

V.8.7

HOUSE FOR SERVANTS OF OUTLYING

ESTATES & SERVANTS TRAVELING

WITH THE EMPEROR'S COURT

This house measures 47½ feet by 60 feet (figs. 402-403)

and lies to the right of the entrance road in a tract entirely

reserved for the raising of livestock; and it is the only one

among the buildings in this sector which is inhabited by

people alone. Its general purpose is described in a hexameter

which reads:

Hic requiem inueniat famulantum turba uicissim

Here, from time to time, let the throng of the

servants find rest

Its layout is a classical example of what in an earlier phase

of this study we referred to as the "standard house" of the

Plan of St. Gall; a house consisting of a central hall with

open fireplace and aisles and lean-to's all around the hall.

The entrance, like those of all the other houses in this tract,

either side of the entrance serve as quarters for the guardians

(cubiʈ custodientiū). The great hall in the center carries the

inscription, "the hall of the serfs who come with the

service" (domƆ famuliae quae cum seruitio aduenerit). Keller,

Willis, Bikel, Leclercq, and Reinhardt[328] interpreted this to

refer to the serfs who live on outlying estates (familia foris)

and come to the monastery in the pursuit of their obligatory

services, delivery of produce, tithe, or harvest; Bischoff

thinks that the house was for the accommodation of servants

who traveled in the following of a visiting ruler.[329] Both

views may be correct, since the seruitium mentioned in the

explanatory title may refer to either or both: the service

due the king or the service due the monastery.[330] The

monastery needed lodgings for the serfs who came with

deliveries from places too distant to allow them to return

to their base on the same day. It also needed lodgings for

the servants who traveled in the king's train. As both of

these potential occupants arrived only intermittently

(uicissim, "as the case may be"), the house may have performed

the double task of giving shelter to both.

With regard to servitium regis, cf. Heusinger, 1923. On the familia

foris and the monastery's relation to outlying estates, see I, 341.

V.8.8

HOUSE FOR KNIGHTS AND VASSALS

WHO TRAVEL IN THE EMPEROR'S

FOLLOWING

ERASURE OF OUTLINES AND DESTRUCTION OF

EXPLANATORY TITLE

The large anonymous building in the northwestern corner

of the monastery remains enigmatic. Its lines and all its

explanatory titles were erased in the twelfth century by the

monk who wrote the Life of St. Martin on the back of the

Plan and spilled his text over onto the front side of the

Plan (fig. 404).[331]

During the nineteenth century an attempt

was made to make the inscription legible with the aid of a

chemical substance, which destroyed it forever.[332]

The chemicals

left strong blue blotches whose distribution reveals

that the house was originally provided with a long title

(unquestionably in metric form), running parallel to the

entrance side of the house, which is east; a shorter title

explaining the function of the large hall in the center; and

other short titles designating the purpose of the rooms in

the aisles and lean-to's. X-ray photographs taken in 1949

by the Schweizerische Landesmuseum at Zurich brought

to light the outlines of the building itself (fig. 405), but

failed to reveal its titles. Ildefons von Arx, in two hand-drawn

annotated copies of the Plan, made around 1827,

remarks, "Von dem Hause sind bloss geringe Spuren übrig

und die angeschriebenen Erklärungen und Bestimmungen

vertilgt. . . . Es scheint aber ebenfalls eine Stallung (vielleicht

für Gastpferde) gewesen zu sein."[333]

Keller apparently could

still read the word cubilia.[334]

This was doubtlessly done by the same hand that tampered with

the titles of the trees in the Monks' Cemetery, fortunately with less

destructive effects. See below, p. 210, fig. 430.

PRESUMPTIVE PURPOSE

I have expressed the view in previous studies that this

building might have been a large barn or wagon shed,[335]

but

I am now inclined to think that it served as quarters for the

emperor's bodyguard. The assumption of a wagon shed is

precluded by the fact—not recognizable to the naked eye

but clearly exposed by the X-rays (fig. 405)—that the only

entrance that gives access to the building is not wide enough

to admit any wagons. Unfortunately, we are not well informed

about the size and composition of the emperor's

bodyguard when he was engaged in travel. In the previously

quoted passage from the Life of Charlemagne, where Einhard

tells that the emperor liked to take his sons and daughters

along on his journeys, Einhard remarks that on such occasions

"his sons would ride at his side and his daughters

follow him, while a number of his bodyguards, detailed for

their protection, brought up the rear."[336]

A hint of the total

number involved in such movements might be contained in

a passage of the Chronicle of Hariulf, where it is said that

the abbot and priors of St.-Riquier, when traveling, enjoyed

the protection of the monastery's entire retinue of

110 mounted knights. As the chronicler proudly adds in

this context, when the knights were gathered at St.-Riquier

during the religious festivals, "their presence lent to the

monastery almost the appearance of a royal court,"[337]

we

must infer that the emperor himself was wont to turn up

with an even larger escort when visiting the abbey.

Heusinger estimates the traveling emperor's court to

have run into the hundreds.[338]

Professor Ganshof would

consider this to be an excessive figure if it were applied to

the Carolingian period.[339]

Obviously, the number of men

who made up such a protective guard must have varied

greatly, depending on the political stability at the time of

travel and the distance involved in the journey,[340]

but one

might safely expect that an elite guard of some twenty to

thirty men accompanied the emperor wherever he went.

The great anonymous building at the northwestern corner

of the monastery site could easily have accommodated a

detachment of this magnitude, and if necessity demanded,

a detachment several times larger. The natural monastic

traffic flow would call for such a barracks to be located in

that corner rather than anywhere else in the rectangular

site into which the monastery is inscribed.

One wonders whether von Arx's conjecture that the

house might have been used for "guest horses," was pure

fantasy or whether his eye could still decipher somewhere

among the obliterated titles the word caballi.

Hariulf, Chronique de l'Abbaye de Saint-Riquier, ed. Lot, 1894,

cf. I, 347. An interesting sidelight on this question is the tabulation

which Meyer von Knonau made in a study of 1872 on the officiales

of the monastery of St. Gall with the aid of the archival resources of this

abbey published by Wartmann. He could establish with certainty that

Abbot Gozbert (816-836) traveled at least on eight different occasions

with his advocatus and five to six further officials, Abbot Bernwick

(837-840) twice with eight officials, and Abbot Grimald (841-872) on

occasion with as many as seven, nine and ten. This information is

gleaned from the signatures attached to deeds which were written in the

course of such travels. The signatures are, of course, confined to those

officials only who by position or rank were qualified to serve as formal

witnesses. The deeds remain silent on the number of servants or knights

who were part of these movements. Ratperti casus s. Galli, ed. Meyer

von Knonau, 1872, Excurs L, 83ff.

Oral communication. I should like to draw attention, in this context,

to an agreement struck in 1056 between the Abbey of Moutier-en-Der

and the Count of Brienne, according to which the abbey was required

to take care of the count, and ten to fifteen knights of his train, when the

count passed through the country: "et si aliquo modo forte ei contigerit

ut per regionem transeat cum decem aut quindecim militibus, ministerialis

Sancti Petri victum ei prebebit;" see Guerard, II, 1844, Appendix XX,

361. In later centuries the traveling train of feudal magnates attained

considerably larger proportions. Sir Thomas of Berkeley II (12811321)

is said to have had a household and a "standing domestic family"

of more than two hundred persons, knights, esquires, serving men and

pages; and Godfrey Giffard, Bishop of Worcester between 1266 and

1302, is reputed to have had a hundred horses in his traveling court.

(I am gleaning this information from Hilton, 1966, 25; for sources see

ibid., 272, notes 1 and 2).

When Charlemagne summoned the young King Louis of Aquitaine

to Paderborn during the Saxon war of 808-809, the latter joined him,

according to a good contemporary source "with his entire military

strength" (cum populo omni militari); and four years later, when Louis

traveled to Aachen, upon the news of his father's death, according to

the same source, "he entered upon his journey with as many people as

the perplexity of the time allowed" (cum quanto passa est angustia temporis

populo), "for it was feared that Wala, possessor of the highest rank

with Charles, might plot something underhanded against the emperor"