THE SPARRENDACH

The Sparrendach is a roof in which a continuous sequence

of coupled rafters of relatively light scantling discharge the

load and thrust of the roof at close intervals and in equal

increments upon the walls or beams on which the rafters

were footed. The most widely known house type employing

this system is the Lower Saxon farmhouse. A closely related

variant of this roof is common in the south and southeast of

England. Zippelius has advanced some cogent arguments

in favor of the assumption that the roofs of the Iron Age

houses of the type of Ezinge, Leens, and Fochteloo belonged

to the family of the Sparrendach,[200]

and this suggests the

possibility that both the German and English variant of

this roof may have a common root in the Continental

homelands of the Saxons and their neighbors, the Frisians.

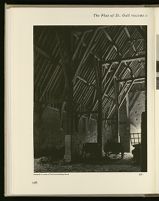

The earliest surviving domestic roof of this construction

type is, to the best of my knowledge, that of the aisled

Infirmary Hall of St. Mary's in Chichester, Sussex, which

dates from the close of the thirteenth century (figs. 341343).[201]

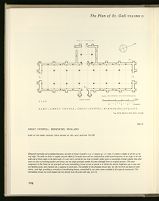

Although this hospital was a private foundation, its

layout follows a pattern that had been established in the

Anglo-Norman monasteries of the two preceding centuries.[202]

It consists of an oblong Infirmary Hall, originally

of six bays but now reduced to four bays, with its entrance

in the middle of the western gable wall. The eastern gable

wall opens into a masonry chapel with richly molded

Early English arches. The Hall itself is 45 feet wide, 43

feet high (clear inner measurements), and originally had a

length of 120 feet. Its roof is sustained by two rows of

wooden posts, framed together, at a height of 21 feet,

lengthwise by means of arcade plates and crosswise by

means of tie beams. The arcade plates are tenoned into a

recess in the head of the principal posts, and the tie beams

are locked into the arcade plates by means of dovetail

joints (fig. 356). The angles between the posts and their

superincumbent long and cross beams are strengthened by a

magnificent set of three-way double bracing struts of

heavy scantling which reduce the free span of the latter to

only a fraction of their total length. The rafters rise in two

flights, at the same angle, first from the wall plates to the

arcade plates, then from the arcade plates to the ridge of

the hall; those of the main roof are restrained from moving

longitudinally by a center purlin pegged into collar beams

and sustained by king posts rising from the center of each

alternate tie beam (figs. 341-342).

St. Mary's Hospital was founded as a temporary home

for the sick and the infirm who were tended by a privately

endowed community of thirteen permanent attendants

under the guidance of a prior and warden. Its elongated

shape is determined by its use as a building for attending

to the needs of a considerable number of people, including

wandering pilgrims and paupers who sought refuge for a

night only.[203]

The contemporary palace and manor halls

were shorter. A typical example of the latter with a classical

Sparrendach was the manor hall of Nurstead Court, Kent

(figs. 344-346). Judging by its architectural style, this hall

must have been built during the period when the manor of

Nurstede was in possession of the Gravensend family and

its construction is generally ascribed to Stephen de Gravensend,

who inherited the manor from his father in 1303,

became Bishop of London in 1318, and died in 1338.[204]

The

hall remained essentially unaltered until around 1837 when

in response to a need for greater comfort in living one half

of it was demolished to make room for a double-storied

structure built in the prevailing taste of the period. The

other half, likewise, was subdivided into several levels and

a variety of rooms, but here the newly inserted walls and

ceilings were suspended in the original frame of timber,

which is intact although no single part of it can be seen in

its entire height. From these remaining parts of the original

fabric and several extraordinary sets of drawings made just

before the hall was altered, by the superb architectural

draftsmen Edward Blore, William Twopeny, and Ambrose

Poynter, the original design of the hall can be reconstructed.

The hall was 34 feet wide and 79 feet long externally.

Its walls were built in flint and rose to a height of 11½ feet

With its ridge the roof reached a height of 36 feet. It was

hipped on both ends and had small triangular gables at the

peak of each hip. The supporting frame of the roof consisted

of three powerful trusses, resting on wooden columns

with molded bases and capitals and arched braces, rising

from the top of the capitals lengthwise to the arcade

plates and crosswise to the tie beams. The latter met in the

center, forming forcefully pointed arches. The tie beams

(like the other principal members, richly molded) are of

unusually heavy scantling and have sharp and elegant

camber. The roof itself is a classical example of the southern

and southeastern English Sparrendach: a continuous sequence

of paired rafters with collar beams pegged to a

center purlin by crown posts that rise from the middle of

each tie beam.

The westernmost bay of the hall was of two stories,

screened off against the two center bays on the ground

floor by timber screens; higher up, by a wall of plaster

reaching all the way up to the ridge of the roof. This end

served as the private quarters for the lord of the manor. The

opposite end of the hall was screened off in a similar manner

by a low timber screen with three doorways; the middle one

opened into a passage that led outside; the two outer ones,

into two rooms which could either have served as quarters

for the servants or as buttery and pantry. The kitchen was in

a separate building to the north of the hall and could be

reached from the latter through a door in the northern long

wall.

The hall of the manor of Nurstead is one of the last

examples of the traditional open hall where the lord and the

servants still lived and ate under the same roof in opposite

ends of the building—an arrangement that is very similar

to, although not identical in all details with that of the

House for Distinguished Guests of the Plan of St. Gall

(fig. 396). The two center bays of the hall were communal

space, which on festive occasions was the stage for banquets

with the open fire burning in the middle of the center

floor, as can be inferred from the smoke blackened beams

and rafters.

At the very same time England had already developed a

new plan, which provided for two double-storied cross

wings at the end of the hall, one of which served as the

private dwelling of the lord and his family; the other, as

quarters for the servants (including space for kitchen,

buttery, and pantry.) A typical example of this new arrangement

is the manor hall of Little Chesterford, Essex, a

plan and perspective reconstruction of which are shown in

figures 347-348. The hall has been ascribed by its earlier

students to about 1275[205]

and by J. T. Smith to about

1320-30.[206]

One of its aisles has been dismantled. Originally

the hall was 27 feet wide and 37 feet long. It was of three

bays with the one near the entrance serving as a narrow

screen-bay. The walls were timber framed, but all other

details were very similar to those of the hall of Nurstead

Court—less forceful and elegant, yet still of genuine refinement.

In the fourteenth century the English lowlands must

have been dotted with countless variants of this type of

hall.[207]