The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V.1.1.. |

JULIUS VON SCHLOSSER, 1889 |

| V.1.2. |

| V.1.3. |

| V.1.4. |

| V. 2. |

| V.2.1. |

| 10. |

| 10. |

| V.2.2. |

| V. 3. |

| V.3.1. |

| V.3.2. |

| V.3.3. |

| V. 4. |

| V.4.1. |

| V.4.2. |

| V.4.3. |

| V. 5. |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

| V. 6. |

| V.6.1. |

| V.6.2. |

| V.6.3. |

| V.6.4. |

| V. 7. |

| V.7.1. |

| V.7.2. |

| V.7.3. |

| V.7.4. |

| V.7.5. |

| V.7.6. |

| V. 8. |

| V.8.1. |

| V.8.2. |

| V.8.3. |

| V.8.4. |

| V.8.5. |

| V.8.6. |

| V.8.7. |

| V.8.8. |

| V. 9. |

| V.9.1. |

| V.9.2. |

| V.9.3. |

| V. 10. |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. |

| V. 11. |

| V.11.1. |

| V.11.2. |

| V.11.3. |

| V. 12. |

| V.12.1. |

| V.12.2. |

| V.12.3. |

| V. 13. |

| V.13.1. |

| V.13.2. |

| V. 14. |

| V.14.1. |

| V.14.2. |

| V. 15. |

| V.15.1. |

| V.15.2. |

| V.15.3. |

| V.15.4. |

| V. 16. |

| V.16.1. |

| V.16.2. |

| V.16.3. |

| V.16.4. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| V.18.1. |

| V.18.2. |

| V.18.3. |

| V.18.4. |

| V.18.5. |

| VI. |

| VI. 1. |

| VI.I.I. |

| VI.1.2. |

| VI.1.3. |

| VI.1.4. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI.2.1. |

| VI.2.2. |

| VI.2.3. |

| VI.2.4. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI.3.1. |

| VI.3.2. |

| VI.3.3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI.4.1. |

| VI.4.2. |

| VI.4.3. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

JULIUS VON SCHLOSSER, 1889

Rahn's reconstruction of the St. Gall house as a basilican

masonry structure with a lantern-surmounted central

hearth had been a purely theoretical venture. He could not

prove—and did not even attempt to prove—that houses of

this description actually existed.

Misconceptions about the "displuviate" and

"testudinate" Roman courtyard house

Julius von Schlosser[10]

tried to overcome this weakness by

demonstrating that Rahn's St. Gall house was historically

the descendant of a once widespread Roman house type to

which the ancients referred with the terms "displuviate"

(displuviatum) and "testudinate" (testudinatum). Schlosser's

theory, unfortunately, was based on two erroneous assumptions

that were current in his day, which imparted to the

discussion of the design of the guest and service structures

of the Plan of St. Gall an element of further confusion.

The first of these misconceptions pertained to the precise

meaning of the terms "displuviate" and "testudinate";

the second concerned the origins and structural evolution

of the Roman atrium house.

To begin with the former: what Vitruvius and Varro

designated by the terms "displuviate" and "testudinate"

can under no circumstances be interpreted as structures

of basilican design. They were atrium houses in the full

constructional sense of the term, i.e., houses in which the

living quarters were ranged around an originally open

center space. The terms "Tuscan", "Corinthian", as well

as "tetrastyle", "displuviate", and "testudinate" (tuscanicum,

corinthium, tetrastylon, displuviatum, and testudinatum)

merely referred to the different degree or manner in which

these inner courtyards were roofed over.[11]

In the Tuscan

atrium house, for instance, the courtyard roof sloped down

toward the center (fig. 265); in the displuviate house it

sloped upward. But in both cases the courtyard roof

encompassed in its center a rainhole (compluvium) that had

under it not a hearth, but a catch basin (impluvium).

Schlosser did not realize that in connecting the St. Gall

house with the displuviate Roman atrium house, he had

actually retrogressed to Lenoir's views (fig. 265), whose

weakness Rahn's reconstruction (fig. 266) had already

successfully overcome.

The same applied to Schlosser's attempt to connect the

St. Gall house with the courtyard house referred to by

Vitruvius and Varro by the term "testudinate." It is an

atrium house like all the others, as must be inferred not

only from the language of the opening sentence with which

ROMAN ATRIUM HOUSE WITH RAIN

CATCH-BASIN

265.B PERSPECTIVE redrawn after Kähler, 1960, suppl. 53, fig. 31

265.C

265.A PLAN, based on Luckenbach, Kunst and Geschichte, I: Altertum,

Munich, 1910, 94

SECTION, authors' interpretation

The plot, 60 feet wide, is 1/2 ACTUS (120 feet)

See remarks on Roman land surveyor's measure, page III. 140

In the form here shown, the Roman atrium house has its open inner

court partially covered by an inward-sloping roof with its center

open to the rain (COMPLUVIUM); beneath this opening in the center

of the court is a collecting basin (IMPLUVIUM). The dining room

(TABLINUM) lies to the rear of the house and opens onto the garden

(HORTUS). The kitchen stove might have been located in any of the

cubicles adjacent to it.

generibus sunt distincta . . ."; "the inner courts of houses

are of five different styles," etc.), but also from the detailed

descriptions that follow ("Testudinata vero ibi fiunt, ubi non

sunt impetus magni et in contignationibus supra spatiosae

redduntur habitationes . . ."; "Testudinate courtyards are

employed when the span is not great, and they furnish

roomy apartments in the story above").[12] In contradistinction

to the other four types in which the courtyard was only

partially roofed over, the testudinate atrium house was a

house in which the inner court was entirely covered. It was

an atrium house in which the courtyard had lost the character

of an open space by being covered over with a second

story, but it was still an atrium house.[13] The Romans used

this type of construction in houses of relatively small

dimensions, as Vitruvius himself suggests, and probably in

response to restricted land conditions prevailing in the

crowded Roman cities.

Vitruvius deals with this subject in De Architectura, Book VI,

chap. 3, par 1; cf. Vitruvii de Architectura Libri Decem, ed. F. Krohn,

1912, 129-30. Varro, in De Lingua Latina, Book V, lines 161ff, ed.

Goetz and Schoell, 1910, 49; ed. Kent, I, 1951, 150-51.

Vitruvius, loc. cit. Varro (ibid.) is even more specific: "Cavum aedium

dictum qui locus tectus intra parietes relinquebatur patulus, qui esset ad

communem omnium usum. In hoc locus si nullus relictus erat, sub divo qui

esset, dicebatur testudo ab testudinis similitudine, ut est in praetorio et

castris. Si relictum erat in medio ut lucem carperet, deorsum quo impluebat,

dictum impluvium, susum qua compluebat, compluvium: utrumque a pluvia,"

i.e., " `Inner Court' is the designation for the roofed part that is left

open within the house walls, for common use by all. If, in this, no place

was left which is open to the sky, it was called a testudo, as it is at the

general's headquarters and in the camps. If some space was left in the

center to get the light, the place into which the rain fell down was called

the impluvium, and the place where it ran together up above was called

the compluvium; both from pluvia, `rain.' "

Frank Granger, in his English version of Vitruvius' De Architectura,

(Vitruvius On Architecture, II, 1934, 25) renders "testudinate," incorrectly

as "vaulted"; Erich Stürzenacker in his German version (Marcus

Vitruvius Pollo, Über Die Baukunst, 1938, no pagination), correctly as

"ganz überdeckte Höfe"; cf. also Pauly-Wissowa, Real-Encyclopädie

der classischen Altertamswissenschaft, IX:1 (1934), col. 1063.

The Roman atrium:

an open yard developing into a covered court

Schlosser's misinterpretation of Vitruvius' and Varro's

definitions of the displuviate and testudinate Roman atrium

house was in itself conditioned by the faulty historical

assumption held by many leading classical archaeologists

at that time, that the Roman atrium was originally not a

court but the principal living room of the house which

gradually developed into an open yard.[14]

This theory was

taken up and widely propagated by one of the greatest

connoisseurs of Roman house construction, August Mau.[15]

But, curiously enough, it had not originated from any

archaeological evidence, which in fact seemed to contradict

it, but from a questionable etymological speculation by

certain Roman authors who believed that atrium came from

ater ("black") and referred to the blackening of the atrium

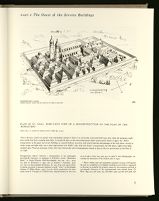

266. PLAN OF ST. GALL. BIRD'S-EYE VIEW OF A RECONSTRUCTION OF THE PLAN OF THE

MONASTERY

MADE FOR J. R. RAHN BY GEORG LASIUS (1876, fig. 12, 91)

This is the first, and for its period, truly outstanding attempt to show in an accurately constructed bird's-eye view, what the monastery might

have looked like had it actually been built. It formed the basis of the three-dimensional model reconstruction shown in figure 267. Rahn's

interpretation of the guest and service buildings as covered basilican structures with central hearths and openings in the roofs above, serving as

smoke escape and light inlet, was a great improvement over Keller's (fig. 264) and Lenoir's interpretation, but like theirs, suffers from being

modeled after Classical prototypes rather than those historically and archaeologically related to those of the era and location of the Plan of

St. Gall.

267. ST. GALL. HISTORICAL MUSEUM OF ST. GALL

ARCHITECTURAL MODEL. A RECONSTRUCTION OF THE BUILDINGS OF THE PLAN

The model was made by the sculptor Jules Leemann of Geneva, in 1877, on the basis of drawings furnished by Georg Lasius and has ever since

been on display in the Historical Museum of the city of St. Gall. It is a masterpiece of its kind, built to scale, and executed with supreme

craftsmanship. Length of base: 70¼ inches (1.78m). Width: 49½ inches (1.25m). The roofs of the houses, as well as the Church, can be lifted,

exposing the furniture on the ground floor levels. The second stories, the Refectory and the Cellar can be lifted out in their entirety. The

reconstruction of Church, Cloister, and Novitiate are essentially correct. The height of the Church (a little over twice the width of the nave) is

excessive for the period. The reconstruction makes no distinction between masonry and timber. Entirely unconvincing is the design of the majority

of the guest and service structures (see caption, figure 266).

of this century, this view has been increasingly challenged

by a trend of thought that holds that, on the contrary,

the Roman atrium was originally an open yard, which

gradually developed into a covered court. The main exponents

of this theory are Antonio Sogliano,[17] Giovanni

Patroni,[18] and Axel Boethius,[19] who believe the Roman

atrium house to be the product of a gradual transformation

of an early Italic farmstead, whose individual buildings

had been scattered loosely around a central open yard, into

an organized architectural system under the hands of the

Etruscan conquerors.

They assume that the principal building of this Italic

farmyard was a prostyle farmhouse with hearth and bedstead.

Through a gradual process of axial co-ordination

of this main house with the subsidiary structures and the

yard enclosure, the Etruscans, according to this theory,

developed the irregular Italic farmstead into the aggregate

depicted in figure 268. Two further developments, in their

opinion, led from this hypothetical prototype form to the

emergence of the classical Roman atrium house, the

"Pompeian primehouse"; the coalescence, namely, of the

roofs of the subsidiary structures with that of the main

house on one hand, and the roofing-over of the courtyard

on the other. As this process unfolds itself, the hearth is

shifted from the original farmhouse (now tablinum) into

one of the adjacent smaller rooms.[20]

Whatever the merits of this theory may be, this much

appears to be certain: we do not know of a single Roman

atrium house, excavated or otherwise attested, that shows

in the center of its covered court either the traces of a

hearth[21]

or any evidence in the roof above it for the existence

of a protective lantern (testudo). In the Roman atrium

house this spot is the traditional place for the catch basin

(impluvium) and directly above it, in the roof, for a rainhole

(compluvium), which also served as air or light source

(fig. 265). The hearth lay, as a rule, in one of the smaller

chambers to the side of the tablinum, or in one of the other

peripheral cubicles, but in any case entirely outside the

atrium space. The testudo of the Roman atrium house, then,

is an altogether different architectural entity from the

device that carries this name on the Plan of St. Gall. The

latter device called testu on the Plan of St. Gall is coextensive

with the hearth site (and could very well be interpreted,

as Rahn suggested, as a protective shield or lantern

that covers an opening in the roof above the hearth); the

testudo of the Roman atrium house by contrast is the designation

for a shielding roof which covers the Roman atrium,

either as a peripheral shed (as in the atrium Tuscanum) or

as a continuous roof (as in the smaller and rarer atrium

testudinatum).

This view, vigorously advanced in Ruge's article "Atrium," in

Pauly-Wissowa, II, 1896, col. 2146ff—"Der Mittelraum des altitalischen

Hauses, welcher ursprünglich den Herd enthielt, und als Speiseraum,

Arbeitsraum der Frauen, überhaupt als gemeinsamer Aufenthalt der

Hausgenossen diente"—became a commonplace in the subsequent

encyclopedic literature. It reappears in Fiechter's article "Römisches

Haus," in Pauly-Wissowa Real-Encyclopädie, 2nd ser., 1A:1, 1914,

col. 983; in Wasmuth, I, 1929, 220; in Schmitt, I Stuttgart, 1937,

col. 1197; in Encyclopedia Britannica, II, 1957, 654; and many others.

A solitary exception is Antonio Sogliano's article "atrio," in Enciclopedia

Italiana, V (Milan-Rome, 1930), 255-56, which summarizes the more

recent views ("Il megaro e il tablino sono, rispettivamente, la vera casa

di cui l'aulé e l'atrio non sono que il cortile") with bibliography concerning

the discussion of this subject prior to 1930.

Mau's widely read and repeatedly reprinted account of Pompeian

life and art, published in an English translation even before it appeared

in German, is probably the primary reason for the tenacious survival in

encyclopedic literature of the superannuated view related above. Cf.

Mau, 1899, 247, and 1904, 253; and idem, 1900, 235-36, and 1908, 258.

The principal source is Servius' Commentaries on Vergil, ed. Thilo

and Hagen, I, 1922, 202: atrium enim erat ex fumo. The derivation of

atrium from ater is only one of several derivations current among Roman

etymologists. Others thought that it came from an Etruscan town, Atria,

where the style of building is supposed to have originated: "alii dicunt

Atriam Etrurii civitatem fuisse, quae domos amplis vestibulis habebant, quae

cum Romani imitarentur, `atria' appellaverant" (ibid.). In modern

etymological literature the term has been connected with Greek αἰθριος

or ὑπαιθρἰος ("under the open sky"), which is more compatible with the

available archaeological evidence, Thesaurus Linguae Latinae, II:1,

1901, col. 1101. But even if it could be demonstrated that ater is the

correct root, we could not infer from this that in the early Roman house

the hearth stood in the atrium, since as long as the open space of the

atrium formed the principal means of escape for the smoke from the

kitchen, the walls and timbers of the court would be blackened even if

the kitchen were located in one of the peripheral chambers.

A great deal of confusion in the discussion of the Roman atrium and

its relation to the hearth has been created by a traditional misinterpretation

of verses 302-3 in book VI of Ovid's Fasti: "at focus a flammis et quod

fovet omnia, dictus; qui tamen in primis aedibus ante fuit." This passage can

under no circumstances be evidence, as Ruge suggests (above, p. 12 n.6),

for the assumption that the hearth stood in the center of the Roman

atrium, and that the latter was in the earlier days the central hearth or

living room of the house. The passage states, "The hearth (focus) is so

named after the flames, and because it warms (fovet) everything; formerly

it stood in the forward part of the house." What Ovid conveys with

this sentence is that, in contradistinction to his own days when the hearth

had no fixed position but could be found in any of the cubicles in the

immediate vicinity of the dining room (tablinum), in the early Roman

house the hearth lay always in the "forward part of the building"—a

statement that would be in full accord with the views expressed by

Sogliani, Patroni, and Boethius—if we were to assume that Ovid's

verses referred to a time in which the roof of the main house had as

yet not coalesced with that of the subsidiary structures into the complex

organism of the Roman atrium house. Cf. Ovidius, ed. Bömer,

I, 1957, 272; and Ovid's Fasti, ed. Frazer, 1951, 340.

That the Roman atrium was at that time thought of as a courtyard

and not as a room, is expressed with unequivocal clarity in Festus'

definition of "atrium": "Atrium proprie est genus aedificii ante aedem

continens aream, in qua collecta ex omni tecto pluvia descendit," i.e., "The

atrium strictly speaking is that part of the building which lies in front of

the dwelling, and contains in its center an area into which the rain

waters fall which are collected by the entire roof." Sexti Pompei Festi

De verborum significatu liber, ed. Wallace M. Lindsay (Leipzig, 1913), 12.

The views of Axel Boethius (ibid.) differ slightly from those of

Sogliano and Patroni. The primary stimulus for the development of the

Roman atrium house, according to Boethius, came from the Orient,

from a type of Near Eastern atrium house of which E. Gjerstad excavated

an excellent specimen at Vouni, Cyprus (Gjerstad, II, 1932). It is from

this type, according to Boethius, that the Etruscans drew the organizing

idea that helped to crystallize the irregular Italic prime forms into an

axially co-ordinated establishment and which, in particular, is responsible

for the tripartite room partition at the head of the atrium, opposite

the entrance (with the tablinum in the center). In essence this arrangement

is identical with that of the Vouni palace, which had three cellae

at the upper end of an open courtyard.

Whatever the differences between Patroni's and Boethius' views may

be, both hold—contrary to the traditional assumption—that the atrium

is by origin an open court that was progressively roofed over, until it

eventually took on the semblance of a room. If this assumption is correct

—and it appears to command wider and wider assent—the rain catch

basin of the Roman atrium house could no longer be considered to be

developmentally the successor of the hearth site of its Italic antecedents.

Even Mau has to admit (1908, 259), "of a hearth in the atrium not

a trace," and from this fact infers that the hearth must have been

"banished from the atrium in a comparatively early date" (idem, 1899,

237; 1904, 254). Of an overwhelming number of excavated Roman

atrium houses only two show traces of a hearth in the inner court of the

house. In one of these the hearth is not part of the original structure

(Nissen, 1877, 448); in the other it stood in one of the corners, not in the

center of the court (ibid., 431).

The ash-urn house of Poggio Gaiella

The same objections have to be raised with regard to Schlosser's

comparison of the St. Gall house with an Etruscan

ash urn from Poggio Gaiella (fig. 269) and other imitations

268. ARCHAIC ETRUSCO-ROMAN HOUSE. RECONSTRUCTION

REDRAWN FROM PATRONI, 1941, 294

Patroni's ideal conception shows the form that the early Italic farmstead had attained after individual buildings, formerly scattered loosely

around an open yard, were axially aligned into an organized architectural scheme by the Etruscan conquerors of the Italian peninsula about the

12th century B.C. The peak of Etruscan culture was achieved during the 6th century B.C.

of some Etruscan tombs. All of these specimens belong

to the courtyard type. They have an opening at the very

spot where the St. Gall house calls for a protective cover,

and there is no suggestion whatsoever that their hearths lay

under this opening or had any functional or developmental

relation to this opening. If the St. Gall house were reconstructed

analogous to the house from Poggio Gaiella, it

would have its hearth on the very spot where every squall

of rain or sleet would kill the fire and drench the occupants

of the adjacent benches and tables. As well as it may have

been adapted to the temperate conditions of a southern

climate, the layout of the house from Poggio Gaiella would

hardly meet the housing requirements of a climate where

heavy downpours and freezing temperatures are matters of

course for periods of considerable duration.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||