The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V.1.1.. |

J. R. RAHN, 1876 |

| V.1.2. |

| V.1.3. |

| V.1.4. |

| V. 2. |

| V.2.1. |

| 10. |

| 10. |

| V.2.2. |

| V. 3. |

| V.3.1. |

| V.3.2. |

| V.3.3. |

| V. 4. |

| V.4.1. |

| V.4.2. |

| V.4.3. |

| V. 5. |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

| V. 6. |

| V.6.1. |

| V.6.2. |

| V.6.3. |

| V.6.4. |

| V. 7. |

| V.7.1. |

| V.7.2. |

| V.7.3. |

| V.7.4. |

| V.7.5. |

| V.7.6. |

| V. 8. |

| V.8.1. |

| V.8.2. |

| V.8.3. |

| V.8.4. |

| V.8.5. |

| V.8.6. |

| V.8.7. |

| V.8.8. |

| V. 9. |

| V.9.1. |

| V.9.2. |

| V.9.3. |

| V. 10. |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. |

| V. 11. |

| V.11.1. |

| V.11.2. |

| V.11.3. |

| V. 12. |

| V.12.1. |

| V.12.2. |

| V.12.3. |

| V. 13. |

| V.13.1. |

| V.13.2. |

| V. 14. |

| V.14.1. |

| V.14.2. |

| V. 15. |

| V.15.1. |

| V.15.2. |

| V.15.3. |

| V.15.4. |

| V. 16. |

| V.16.1. |

| V.16.2. |

| V.16.3. |

| V.16.4. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| V.18.1. |

| V.18.2. |

| V.18.3. |

| V.18.4. |

| V.18.5. |

| VI. |

| VI. 1. |

| VI.I.I. |

| VI.1.2. |

| VI.1.3. |

| VI.1.4. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI.2.1. |

| VI.2.2. |

| VI.2.3. |

| VI.2.4. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI.3.1. |

| VI.3.2. |

| VI.3.3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI.4.1. |

| VI.4.2. |

| VI.4.3. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

J. R. RAHN, 1876

Probably aware of these inconsistencies in Keller's and

Lenoir's interpretations, the Swiss art historian J. R. Rahn

presented a new solution in 1876, which was incorporated

into a graphical reconstruction of the entire settlement in

a bird's-eye view drawn up for him by Georg Lasius

(fig. 266).[5]

Without explicitly refuting or even discussing

Keller's and Lenoir's views, Rahn reconstructed the St.

Gall house as a masonry structure of basilican type with a

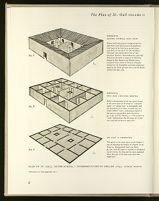

PLAN OF ST. GALL. OUTER SCHOOL.[6] INTERPRETATION OF KELLER (1844). AUTHORS' DRAWING

264.C PERSPECTIVE

SHOWING INTERNAL OPEN COURT

Houses with living quarters ranged around an

open inner court were in use in the Euphrates

river basin in the Isin Larsin period (20241763

B.C.) in the city of Ur (H. Frankfort,

The Art and Architecture of the

Ancient Orient, Harmondsworth, 1958, 66).

They form the point of origin of an illustrious

lineage of Near Eastern and Mediterranean

courtyard houses which in Classical Antiquity

evolved into the beautifully conceived symmetrical

layout of the Greek peristyle house and the Roman

atrium house (fig. 265).

264.B PERSPECTIVE

WITH ROOF STRUCTURE REMOVED

Keller's interpretation of the two squares drawn

in the center space of this house as "courtyard

houses" or "garden huts" is incompatible with

the annotation of the Plan, on which they are

clearly labeled "testu", indicating a feature of

the roof on a ground floor plan. See below,

pp. 117ff, and III, Glossary, s.v. The presence of

"testu" demonstrates that the house was roofed

over, and did not have an open court.

264.A THE PLAN IN PERSPECTIVE

The squares in the center space are the designer's

way of indicating the location of a hearth. In the

House for Distinguished Guests (see below,

pp. 146, 160) this square is explicitly so designated

(LOCUS FOCI). For this and the reason explained

above, this part of the house must have been

roofed over.

rooms and received its light through clerestory windows.

The squares that are inscribed in the Plan alternately as

locus foci and testu[do] Rahn interprets as open fireplaces

surmounted on the level of the main roof by a lantern with

openings for the escape of smoke. This solution was suggested

to him by similar architectural contraptions "still

nowadays in use in certain rural houses of northern

Germany and also occasionally found in England."[7] Rahn's

reconstruction has subsequently found the widest circulation

by being reproduced in Cabrol-Leclercq's Dictionnaire

d'archéologie chrétienne.[8] It also formed the basis for a

masterful three-dimensional model, executed in 1877 by

Julius Lehmann, which found a permanent home in the

Historisches Museum of the city of St. Gall (fig. 267).[9]

The advantages of Rahn's reconstruction over those of

Keller and Lenoir are obvious at first sight. It establishes

correctly, and in accordance with the legends of the Plan,

the large rectangular center space of the house as a covered

room. Second, it associates the term testu[do] with a

device that is compatible with its etymology (protective

shield, or cover). Third, it offers a constructive solution to

the interchangeability of the terms testu[do] and locus foci,

since "hearth" and "lantern," if arranged in the manner

Rahn suggested, would merely be two complementary

aspects of the same device—namely, an open fire with a

smoke hole in the roof surmounted by a lantern.

The statement is not further substantiated. Rahn, however, was not

the first to suggest such a solution. It was considered as early as 1848 by

Robert Willis (1848). Willis' interpretation of the St. Gall house vacillates

between that of Keller, whom he follows closely in his general

description of the Plan, and suggestions that could be called anticipations

of Rahn's and Lenoir's views, as may be gathered from the following

quotations: in connection with the House for Distinguished Guests

(p. 90): "This central room either rose above the roofs of the others,

so as to allow for small open windows like clerestory windows, or else the

central room was so roofed over as to leave a small square opening in the

middle, which admitted light and allowed the smoke of the fire to escape.

In warm southerly climates, as at Pompeii, the opening had a cistern

below to receive rain. But in the north, if a fire-place was below it, the

central opening must have been covered with a sort of turret or lantern,

with open sides, to prevent the rain from pouring down upon the fire";

with regard to the other buildings (p. 91): "I am inclined to think that

. . . the central square in most of the examples . . . represents the central

opening of a roof, which roof may either slope outwards or inwards, as

the case may be"; with regard to the farm buildings (p. 91): "In the

great farm buildings at the south-west part of the establishment the

small central square may indicate that the central space has an overhanging

shed carried round it, leaving the opening in the middle; or if

this appears improbable, we must suppose in this case that it means a pond

for water, or, as Keller seems to think, a little cabin or sentry-box,

which I confess does not appear very likely."

On the history of the construction of this model see Edelmann, in

Studien, 1962, 291-95. The model in turn served as prototype for a

painting made by B. Steiner in 1903 for use in school instruction, which

shows the monastery from the south east. This painting has never been

published, so far as I have been able to determine. It places the settlement

shown on the Plan of St. Gall into the topographic relief of the

site on which the monastery of the Abbey of St. Gall rose. Since it adds

nothing to the concept of the buildings established by Rahn and Lasius,

I pass over it.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||