The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| II. |

| V. |

| V. 1. |

| V.1.1.. |

| V.1.2. |

| V.1.3. |

| V.1.4. |

| V. 2. |

| V.2.1. |

| 10. |

| 10. |

| V.2.2. |

| V. 3. |

| V.3.1. |

| V.3.2. |

| V.3.3. |

| V. 4. |

| V.4.1. |

| V.4.2. |

| V.4.3. |

| V. 5. |

| V.5.1. |

| V.5.2. |

| V. 6. |

| V.6.1. |

| V.6.2. |

| V.6.3. |

| V.6.4. |

| V. 7. |

| V.7.1. |

| V.7.2. |

| V.7.3. |

| V.7.4. |

| V.7.5. |

| V.7.6. |

| V. 8. |

| V.8.1. |

| V.8.2. |

| V.8.3. | V.8.3 |

| V.8.4. |

| V.8.5. |

| V.8.6. |

| V.8.7. |

| V.8.8. |

| V. 9. |

| V.9.1. |

| V.9.2. |

| V.9.3. |

| V. 10. |

| V.10.1. |

| V.10.2. |

| V.10.3. |

| V.10.4. |

| V. 11. |

| V.11.1. |

| V.11.2. |

| V.11.3. |

| V. 12. |

| V.12.1. |

| V.12.2. |

| V.12.3. |

| V. 13. |

| V.13.1. |

| V.13.2. |

| V. 14. |

| V.14.1. |

| V.14.2. |

| V. 15. |

| V.15.1. |

| V.15.2. |

| V.15.3. |

| V.15.4. |

| V. 16. |

| V.16.1. |

| V.16.2. |

| V.16.3. |

| V.16.4. |

| V. 17. |

| V.17.1. |

| V.17.2. |

| V.17.3. |

| V.17.4. |

| V.17.5. |

| V.17.6. |

| V.17.7. |

| V.17.8. |

| V. 18. |

| V.18.1. |

| V.18.2. |

| V.18.3. |

| V.18.4. |

| V.18.5. |

| VI. |

| VI. 1. |

| VI.I.I. |

| VI.1.2. |

| VI.1.3. |

| VI.1.4. |

| VI. 2. |

| VI.2.1. |

| VI.2.2. |

| VI.2.3. |

| VI.2.4. |

| VI. 3. |

| VI.3.1. |

| VI.3.2. |

| VI.3.3. |

| VI. 4. |

| VI.4.1. |

| VI.4.2. |

| VI.4.3. |

| VI. 5. |

| VI.6. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

V.8.3

HOSPICE FOR PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS

THE MAIN HOUSE

The Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers (fig. 392) lies to

the south of the Church and west of the cloister in a yard

that is bounded to the east by the Monks' Cellar and Larder,

to the south and west by fences that separate the pilgrims

and paupers from the houses for the livestock and their

keepers, and to the north by the semicircular atrium of the

Church. Access to this yard is gained by a porch built

against the southern wall of the atrium, which also serves

as entrance for the monastery's servants. The house is

identified by the hexameter, "Here let the throng of pilgrims

find friendly reception" (hic peregrinorum la&etur

turba recepta).

The Hospice is composed of a main house for the reception

of the pilgrims and paupers, and an annex containing

kitchen, bakery, and brewing facilities. The main house

measures 50 by 60 feet. It has in its center a large rectangular

room that is designated as "living room" or "hall for

the pilgrims and paupers" (domus peregrinorum et pauperėm).

This space must also have served as dining room, as may

be gathered from the benches that run all around its circumference.

The draftsman did not enter the tables, but

the meaning of this seating arrangement is clear from the

corresponding space in the House for Distinguished Guests.

The house receives its warmth from a large central fireplace,

and the smoke escapes through a louver (testu) in the roof

above it.[291]

Two rooms on the front side of the house are

used as quarters for the servants (seruientium mansiones),

two corresponding rooms at the rear as "supply room"

(camera) and "cellar" (cellarium). The spaces under the

lean-to's on the narrow sides of the house serve as dormitories

for the pilgrims and paupers (dormitorium and

aliud). The Statutes of Adalhard, written at about the same

time (822) that the Plan of St. Gall was drawn, make it

clear that the normal number of pilgrims expected to spend

the night in the monastery of Corbie was twelve[292]

—this

corresponds quite closely to the number of pilgrims who

could be housed in the rooms which in the Plan of St. Gall

are designated as dormitories for pilgrims. They are capable

of accommodating eight beds each, ranging in a single row

all around the walls of the room. But, in an emergency, of

course, the bedding capacity of the Hospice for the paupers

could be increased by a wide margin, if the benches in the

hall were used as additional facilities for sleeping.

The Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers is wanting of that

other convenience so profusely attached to the houses that

shelter the upper social strata of the monastic community:

the privy. I have already had occasion to remark that I do

not think that this is an oversight.[293]

PLAN OF ST. GALL. LODGING OF THE PORTER

395.A

395.B

The Porter's Lodging, with its corner fireplace, private privy, quarters for as many as five

assistants, and garden, reflects the importance of this official in monastic life; his quarters

were nearly twice the size of those of the Master of the Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers, his

subordinate. St. Benedict stipulated that the Porter be selected with special care, for he was

charged with the reception of all guests and the distribution of food and services to fill all

their needs. His role was diplomat and administrator.

In particular his duties were to identify and greet distinguished guests of the monastery and

their retinues, and then see to their escort through the north reception porch into the grounds

and quarters provided for them in the House for Distinguished Guests and its Annex.

Guests of high social standing might have business with the internal life of the monastery,

but their reception area, though larger and better appointed than that for pilgrims and

paupers, was likewise closed off from any direct access to the inner monastery grounds;

similarly, unnecessary contact of such guests with the less exalted class of traveler lodged

upon the south was by these arrangements largely precluded.

1. Church- Ie. Lodging of the Porter- If. Porch of the Porter- Ig. Porch of Reception-Ik.

Tower of St Michael- 10. Kitchen, Bake & Brewhouse for Distinguished Guests- K.

Kitchen- L. Larder- B. Bakery- BH Brewery- 11. House for Distinguished Guests- DH

Dining Hall.

We have reconstructed the Hospice for Pilgrims and

Paupers as a large rectangular hall with central hearth and

louver in the roof above it, the hall being surrounded on

all four sides by aisles or lean-to's (fig. 393A-E). In view

of the constructional characteristics of the genus of houses

to which the guest and service buildings of the Plan of St.

Gall historically belong, it is reasonable to assume that the

roof of this, as well as of all other related houses of the Plan,

is carried by a frame of timber, consisting of two rows of

posts connected crosswise by tie beams and lengthwise by

post plates. The natural and historical place for alignment

for these two rows of posts are the lines that define the

boundaries between the aisles and the central hall of the

house. Since the Plan does not designate the location of the

structural members in this type of house, but confines

itself merely to delineating the boundaries of its component

spaces, we know nothing about the respective distances of

the roof-supporting posts. Ours are purely conjectural.

There is a variety of other possibilities.

As there is only one source of heat for both the hall and

the peripheral spaces, the latter can only have been partially

boarded off against the center hall. The separating wall

paneling may not have risen much higher than the backrest

of the benches that surround the hall. We have reconstructed

the roof as a simple rafter roof (of the type exemplified

by St. Mary's Hospital in Chichester, figs. 341-343), but

the roof might have belonged as well to the family of purlin

roofs.

We are well informed about the function and management

of the Hospice for Paupers through the Administrative

Directives of Adalhard of Corbie.[294]

The management

of the Hospice for Paupers, we learn from this account, was

in the hands of the Hosteler (hostellarius) who was subject

to the directives of the Porter (portarius). On the Plan of

St. Gall the Hosteler is accommodated in a special apartment

which abuts the southern aisle of the church immediately

to the side of the Hospice for Paupers. The rooms

that are designated camera and cellarium in the Hospice for

Paupers are the Hosteler's food and supply rooms.

Adalhard orders that each pilgrim was to receive, each

day, a loaf of bread, weighing 3½ pounds and made of a

mixture of wheat and rye, and that on his departure he was

to be issued half a loaf of the same kind for his journey.

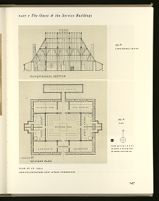

396. PLAN OF ST. GALL

HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS, WITH ANNEX CONTAINING KITCHEN, BAKE & BREWING FACILITIES

The layout of this structure is in its basic dispositions the same as the Hospice for Pilgrims and Paupers. It also consists of a main house with

an annex to accommodate services involving fire hazards. Likewise the main house here consists of a central hall for dining and a subsidiary

suite of outer rooms used for sleeping, the accommodation of servants, and when appropriate, even horses. But the layout of the House for

Distinguished Guests is more explicit than its humbler counterpart. Here with great precision is portrayed placement of tables and benches in

the center hall, as well as the furnishings in bedrooms of the Distinguished Guests. These rooms are provided with corner fireplaces, making

their comfort independent of the open fireplace in the middle of the center hall, and thus affording their occupants the luxury of privacy. The

presence of these corner fireplaces induced us to assume that the outer walls of this house were intended to be of masonry.

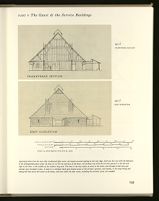

The use of masonry and timber in a royal Carolingian hall is well attested through an important literary source, the Brevium Exempla

(p. 36ff, above), where the DOMUS REGALIS of an unnamed estate near Annapes is described as being constructed in timber "in the usual

fashion." This remark reveals that wood was the more common and traditional material for this house type. Hipped roofs are attested for the

windswept continental coastlands of the North Sea from the 7th century B.C. onward (figs. 295-297 and 314, above) and became a permanent

trait of rural architecture north of the Alps (figs. 335-336, above).

Windows are not part of the customary design of this house type. They became an indispensable adjunct when its outer rooms were partitioned,

separating them from the only other traditional light source: the lantern-covered opening in the roof ridge. Such was the case with the bedrooms

of the distinguished guests under the lean-to's of the two end bays of the house, and perhaps even with the servants quarters to the left and

right of the door, in the middle of the southern long wall. This door is the only means of access to the house, and through it both men and

animals were intended to pass. It leads to a vestibule which gives lateral access to the servants' quarters, and axially, to the large living and

dining hall that forms the center of the house, and from which all other rooms, including the servants' privy, are reached.

PLAN OF ST. GALL

397.B LONGITUDINAL SECTION

397.A PLAN

HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

PLAN OF ST. GALL

397.C SOUTH ELEVATION

397.D NORTH ELEVATION

HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

397.E TRANSVERSE SECTION

397.F EAST ELEVATION

398. PLAN OF ST. GALL. HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS

AUTHORS' RECONSTRUCTION

This perspective shows the large center nave of the house, the communal living and dining area, and bedrooms of servants to the left, with

stables to the right. Tables and benches ranged around the walls of the center space presumably could be rearranged to meet particular needs of a

group of guests, or moved back altogether when not in use.

In each building of the Plan housing both animals and men, the layout is similar: servants' quarters flank (or guard) the entrance while

animals pass through the common room to the rear. This disposition may reflect a defensive posture of ancient antecedents. In the House for

Distinguished Guests it had the further convenience of proximity to the privy where, as an amenity afforded guests of high rank, refuse and

manure from the stables might be readily disposed of.

Carpentry details shown here derive from later medieval examples (cf. page 115ff, above); but the concept of a timber-framed roof dividing

the house into nave, aisles, and bays, is clearly in the historical tradition of the Germanic all-purpose house to which the preceding chapters

have been devoted.

This exterior view shows, in the left foreground of the main house, the privy for servants and guards. In the right background lies the annex

containing kitchen, baking, and brewing facilities. Bedrooms for distinguished guests, with individual corner fireplaces and private toilets, are

under the hips of the roof on the two narrow sides of the house. Stables are in the northern aisle parallel to the servants' privy. Bedrooms of

the latter are on the entrance side (not visible here).

399. ST. GALL

HOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS; ALSO ITS KITCHEN, BAKE, AND BREW HOUSE

issued a quarter loaf of bread per head.

The daily ration in the Hospice also included two tankards

of beer, but whether or not any wine could be served

was left to the judgment of the prior. Special consideration

was to be given to the sick pilgrims, and to those who came

from distant lands, for whom the Hosteller could draw

additional rations "so that he should not incur any shortages

in his normal allotments." Provisions not spent on the

days when the number of visitors fell below the expected

norm were to be saved and used as a surplus to be drawn

against on days when the norm was exceeded.

Adalhard specifies the source and volume of beans, lard,

and cheese, as well as the amount of eel and meat, and all

of the other indispensible items, not omitting the "old

clothes and shoes of the monks, which the Hosteler receives

from the Chamberlain for distribution to the paupers

as is customary." He lists the amount of money that should

be distributed among the poor, pointing out that no rigidly

binding rules could be established in this delicate matter

where varying needs require varying action, and he terminates

this chapter of his statute with the wistful admonition:

"We therefore beseech all those upon whom this office will

be bestowed in our monastery that, in their generosity and

distribution, they bow to the will of God rather than to their

own parsimoniousness, since everyone is to be rewarded

according to the pattern he has set for himself."[295]

With regard to the meaning of this term, cf. above pp. 117ff. Keller's

(1844, 27) and Willis' (1848, 108-9) assertion that the Hospice of the

Paupers is devoid of a fireplace and a dining room is based on an untenable

interpretation of the square in the center of this house, designated

with the word testu, as a "garden hut," and on a misunderstanding of

the term domus, which does not refer to the whole of the house but

only to the common hall for the pilgrims and paupers in the center of

the house. Cf. above pp. 77-78.

Consuetudines Corbeienses, chap. 2, ed. Semmler, in Corp. Cons.

Mon., I, 1963, 372: duodecim pauperes qui supra noctem ibi manent.

THE KITCHEN, BAKE AND BREW HOUSE FOR

PILGRIMS AND PAUPERS

The Kitchen, Bake and Brew House for Pilgrims and

Paupers lies ten feet west of the Hospice, and covers a

surface area of 22½ feet by 60 feet. Its layout repeats on a

400. PLAN OF ST. GALL

KITCHEN, BAKE AND BREWHOUSE FOR DISTINGUISHED GUESTS. AUTHORS' RECONSTRUCTION OF

ROOF FRAMING, WITH SOME TIMBERS REMOVED

A widened aisle forms an extended lean-to accommodating kitchen and larder on either side of the entrance. The wall plate for the main space

of the house provides footing for rafters over this enlarged lean-to. In the nave space are the oven, kneading troughs, and tables for shaping

loaves. At right are the brewing range and four tubs or cauldrons for steeping brew. The narrow aisle beyond and to the rear (its interior not

visible here) is of conventional width in relation to the main space, and houses at one end containers for cooling beer and at the other, troughs

for leavening dough.

Monks, which shall be discussed later on. But it combines

with the facilities for brewing (bracitoriū) and baking

(pistrinū) a stove for cooking. This is the meaning that must

be attributed to the square in the bakery immediately in

front of the baking oven (fornax), which is internally divided

into four more squares by two lines crossing each other at

right angles. The same symbol is used for the stove in the

Kitchen for the Distinguished Guests.[296] There, in the

center, of a room, explicitly defined as "kitchen" (culina),

its meaning is unequivocal. The facilities for cooling the

beer (ad refrigerandū ceruisā) and for leavening the bread

(locus conspergendi) are installed in the aisle that runs along

the western side of the house. The equipment is identical

with that of the Bake and Brew House of the Monks, and

the design and construction of the house must also have

been very similar.

See below, p. 165. Keller (1844, 27) and Willis (1848, 108-9)

overlooked this fact and based upon this `oversight' the erroneous conclusion

that the Hospice was not furnished with a kitchen.

Charles W. Jones reminds me, in this context, of a passage in the

Directives of Abbot Adalhard of Corbie containing a strong hint that at

Corbie too, the poor had their own kitchen: "According to custom the

porter should provide firewood for the poor, or other things which are not

recorded here, such as the kettle or dishes or other things that are in their

quarters". See III, 106, and Consuetudines Corbeienses, ed. Semmler,

Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963, 374.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||