RELATIVE CHRONOLOGY

Unfortunately, we do not know precisely when Hildebold's

church was started; therefore, it was to be expected

that Doppelfeld's view of its priority over the Church of

the Plan of St. Gall should be challenged. Adolph Schmidt

voiced the opinion that both buildings might have a

common root in a prototype plan developed during the

two reform synods of Aachen (816-817).[167]

Irmingard

Achter, Albert Verbeek, and Fried Mühlberg went so far

as to question the Carolingian origin of Cologne Cathedral

altogether and ascribed it to the time of Archbishop

Bruno (953-956).[168]

Doppelfeld never budged from his

original position[169]

and further excavations seemed to

confirm his view. In a careful and exhaustive re-analysis of

the entire archaeological and documentary evidence available,

Otto Weyres[170]

arrived at the conclusion that the

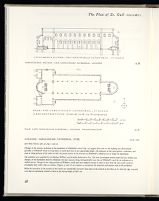

concept of the church, the foundations of which are

shown in figure 14, is essentially that of Archbishop

Hildebold—a concept created on its initiative under the

impact of the enhanced significance that the empire of the

Franks had acquired through the coronation of Charlemagne

at Rome in the year 800—and for that reason

probably put into effect in the years immediately following

this important event. Hildebold, who held the position of

arcicapellanus at the court of Charlemagne, had witnessed

with his own eyes the construction, step by step, of the

Palace Chapel, Aachen (ca. 790-800). His own cathedral at

Cologne with its thin walls, then already 300 years old,

had become outdated. Before the year 800 Hildebold had

already made an attempt to enlarge it westward with a

semicircular atrium (by more than 20 years older than the

semicircular atria of the Plan of St. Gall).[171]

After the

coronation of Charlemagne in Rome, Weyres argues,

Hildebold took the decisive step of tearing down the entire

ancient fabric of the Merovingian cathedral and of laying

the foundations for a new one (fig. 15): an aisled church

with apse and counter apse, a western transept, and an

extended eastern choir. The foundations of this building

(VIIa) are well attested, yet nothing is known about its

elevation. When Hildebold died in 819, the project was not

finished, but it must have been sufficiently advanced at

this time to be identified with him by later generations.

Certain conditions of the masonry and the soil suggest

that after Hildebold's death, construction was disrupted or

moved very slowly. There is good reason to believe that

the building was close to completion when Archbishop

Gunther was deposed in 864, since in the troubled six

years that followed not much could have been done.[172]

The

church was solemnly dedicated by Archbishop Willibert

on September 27, 870 in the presence of the archbishops

of Mainz, Trier, and Salzburg and all of the suffragans.[173]

The imprints of two piers on the foundation of the northern

row of arcades disclose that the nave walls of this building

(VIIb) were supported by piers, 5.67 m. long (15 Roman

feet), at a clear interstice of 4.17 m. (14 Roman feet). A

reconstruction of this church, as proposed by Weyres, is

shown in figures 15 and 16. There is no conclusive evidence

that the elevation of this church was identical with that

which Bishop Hildebold had in mind. The imprints of its

pillars were found on a level of the foundations that seemed

to lie above the fabric completed at the time of Bishop

Hildebold.

Weyres' conclusions about the date and building sequence

of Cologne Cathedral are persuasive and suggest

that if there were any conceptual links between the Church

of the Plan of St. Gall and the Carolingian cathedral of

Cologne, it was the latter that influenced the former, as

Doppelfeld had proposed in the first place, and not the

other way round.