I.9.1

SOME REFLECTIONS ABOUT IT AND

ITS RELATION TO THE

CAROLINGIAN CATHEDRAL

OF COLOGNE

CONCEPTUAL AFFINITIES WITH

COLOGNE CATHEDRAL

With its emphasis on the monastery as a general cultural

institution[160]

and its generous allotment of space provided

for the reception of secular dignitaries[161]

the layout of the

Plan of St. Gall displays a largesse d'esprit that appears

more akin to the educational and administrative policies

promoted by Charlemagne and his advisors than to the

constrictive atmosphere prevalent in monastic life at the

time of Louis the Pious.

Nowhere is this boldness of approach more clearly

disclosed than in the exuberant dimensions of the Church

of the Plan. Prior to 1948 the idea that an exemplary

Carolingian monastery church could attain a length of 300

feet appeared doubtful to many. The Abbey Church of

Fulda, 321 feet long and 100 feet wide, had always been

considered exceptional, and the rebellion of the monks of

Fulda against its inordinate size appeared to confirm this

view.[162]

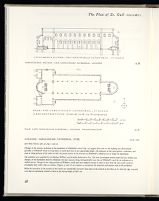

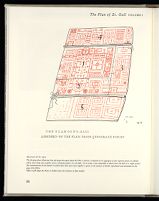

But Otto Doppelfeld's excavation of the foundations

of the Carolingian church of Cologne brought to

light under the pavement of the present Cathedral the

remains of a church that corresponded to the Church of

the Plan of St. Gall not only in size but also in the essentials

of its layout (figs. 14-16).[163]

A late but trustworthy tradition

ascribes the construction of this edifice to Archbishop

Hildebold of Cologne (787-818),[164]

a relative of Charlemagne

and one of his most trusted councilors.[165]

Like the Church of the Plan of St. Gall, the church of

Hildebold was about 300 feet long and about 80 feet wide.

As in the former, the nave in the latter had a width of about

40 feet, and the aisles half of that, about 20 feet. In both

churches the transept arms and the fore choir repeat the

dimensions of the crossing square. Both churches had

apses at either end, a semicircular paradise with a covered

walk in the west and an uncovered paradise in the east.

The similarities are very close and so striking, Doppelfeld

concluded, that one must have served as model for the

other. In the plan of the church of Cologne, he believed,

he had found the prototype for the layout of the Church

of the Plan of St. Gall.[166]

RELATIVE CHRONOLOGY

Unfortunately, we do not know precisely when Hildebold's

church was started; therefore, it was to be expected

that Doppelfeld's view of its priority over the Church of

the Plan of St. Gall should be challenged. Adolph Schmidt

voiced the opinion that both buildings might have a

common root in a prototype plan developed during the

two reform synods of Aachen (816-817).[167]

Irmingard

Achter, Albert Verbeek, and Fried Mühlberg went so far

as to question the Carolingian origin of Cologne Cathedral

altogether and ascribed it to the time of Archbishop

Bruno (953-956).[168]

Doppelfeld never budged from his

original position[169]

and further excavations seemed to

confirm his view. In a careful and exhaustive re-analysis of

the entire archaeological and documentary evidence available,

Otto Weyres[170]

arrived at the conclusion that the

concept of the church, the foundations of which are

shown in figure 14, is essentially that of Archbishop

Hildebold—a concept created on its initiative under the

impact of the enhanced significance that the empire of the

Franks had acquired through the coronation of Charlemagne

at Rome in the year 800—and for that reason

probably put into effect in the years immediately following

this important event. Hildebold, who held the position of

arcicapellanus at the court of Charlemagne, had witnessed

with his own eyes the construction, step by step, of the

Palace Chapel, Aachen (ca. 790-800). His own cathedral at

Cologne with its thin walls, then already 300 years old,

had become outdated. Before the year 800 Hildebold had

already made an attempt to enlarge it westward with a

semicircular atrium (by more than 20 years older than the

semicircular atria of the Plan of St. Gall).[171]

After the

coronation of Charlemagne in Rome, Weyres argues,

Hildebold took the decisive step of tearing down the entire

ancient fabric of the Merovingian cathedral and of laying

the foundations for a new one (fig. 15): an aisled church

with apse and counter apse, a western transept, and an

extended eastern choir. The foundations of this building

(VIIa) are well attested, yet nothing is known about its

elevation. When Hildebold died in 819, the project was not

finished, but it must have been sufficiently advanced at

this time to be identified with him by later generations.

Certain conditions of the masonry and the soil suggest

that after Hildebold's death, construction was disrupted or

moved very slowly. There is good reason to believe that

the building was close to completion when Archbishop

Gunther was deposed in 864, since in the troubled six

years that followed not much could have been done.[172]

The

church was solemnly dedicated by Archbishop Willibert

on September 27, 870 in the presence of the archbishops

of Mainz, Trier, and Salzburg and all of the suffragans.[173]

The imprints of two piers on the foundation of the northern

row of arcades disclose that the nave walls of this building

(VIIb) were supported by piers, 5.67 m. long (15 Roman

feet), at a clear interstice of 4.17 m. (14 Roman feet). A

reconstruction of this church, as proposed by Weyres, is

shown in figures 15 and 16. There is no conclusive evidence

that the elevation of this church was identical with that

which Bishop Hildebold had in mind. The imprints of its

pillars were found on a level of the foundations that seemed

to lie above the fabric completed at the time of Bishop

Hildebold.

Weyres' conclusions about the date and building sequence

of Cologne Cathedral are persuasive and suggest

that if there were any conceptual links between the Church

of the Plan of St. Gall and the Carolingian cathedral of

Cologne, it was the latter that influenced the former, as

Doppelfeld had proposed in the first place, and not the

other way round.

LIKELIHOOD OF HILDEBOLD'S INVOLVEMENT

IN ORIGINAL SCHEME

My own analysis of the Plan of St. Gall and its relation

to the monastic reform movement[174]

has made a good case

for the assumption that someone, or some group, at

Aachen had been charged with the responsibility of working

out a master plan which was to show how the resolutions

taken by the assembled abbots and bishops about monastic

life and ritual reflected themselves in the physical layout

of an exemplary monastery. Bishop Hildebold, or someone

close to him, may have been in charge of this project. The

emphasis that it gives to houses used for the reception of

visitors—and in particular to the reception of the emperor

and his court—[175]

makes one want to assign it conceptually

to a man who grew up in the time of Charlemagne rather

than in the time of Louis the Pious. These facilities are

treated with special care, if not a touch of lavish attention,

and give the impression of being devised by a man who

was not only thoroughly familiar with the architectural

needs of the traveling emperor, but also sufficiently convinced

of the unison of regnum and sacerdotium in the

office of the sovereign to justify the inclusion of that much

space for his reception on the hallowed grounds of a

monastery.

We do not know to what extent the prototype plan was

formally approved at Aachen. It may have been discussed

and endorsed in toto. Or it may have been accepted with

certain specific reservations. Some issues, as we have seen,

were controversial.[176]

It was Boeckelmann who first expressed the intriguing

view that at the two synods of Aachen, two parties were

wrestling about the aims of the future reform of the church:

an "old guard" who had reached the peak of their career

under Charlemagne and were now gradually dying out,

and another group of men who supported St. Benedict of

Aniane in his advocacy of more constrictive reforms.[177]

My

own studies of Bishop Haito's commentary to the preliminary

acts of the first synod[178]

and Semmler's analysis

of the antagonistic views held by such men as Abbot

Adalhard of Corbie (who was put into exile before the

synods started)[179]

have confirmed this view. There is good

cause to believe that among the various topics that were

subject to controversy at Aachen—such as the permissibility

of baths,[180]

the issue of whether there should be a

secular school in the monastery,[181]

and the delicate problem

of where the abbot should sleep and eat—[182]

was also the

question of the optimal length of the church.

In 817 Abbot Ratgar of Fulda was deposed from his

abbacy by Emperor Louis the Pious, apparently on the

ground that Abbot Ratgar, in erecting at Fulda the largest

church then existing north of the Alps (321 feet long and

100 feet wide), had taxed the brothers' physical and mental

resources beyond endurance, ruined the monastery's

economy, and shortened the lectio divina, neglected the

traditional hospitality due pilgrims and other guests, and

forced the monks to violate time-honored customs in

many other ways.[183]

These events show clearly enough that

the issue of what the desirable length of a monastic church

should be was very much alive at the time of the synods.

It is quite possible, therefore, that the reduction of the

length of the Church of the Plan of St. Gall from 300 feet

(shown in the drawing) to 200 feet, as stipulated in one of

its explanatory titles is, as Boeckelmann suggested, not the

expression of a change of spirit that occurred between the

time when an original scheme was drawn (816-817) and

the time when the copy was made (around 820), but a

corrective measure imposed upon the original scheme

when it was discussed and endorsed at Aachen.[184]

In

adopting this change in his copy, Bishop Haito did not

take it upon himself to alter the drawing. He retraced the

layout of the prototype plan as he found it on the original

drawing.

AN ORNAMENTAL DETAIL SUGGESTING THE

COURT SCHOOL AS THE CONCEPTUAL HOME OF

THE PROTOTYPE PLAN

There is an interesting ornamental detail on the Plan of

St. Gall which suggests that the prototype plan might,

indeed, have been drawn by a hand that was trained in the

scriptorium of the court of Charlemagne, namely the

"tendril"-shaped design which designates the trees in

the Monks' Cemetery (fig. 17).[185]

This motif has close

parallels in a group of sumptuously illuminated manuscripts

formerly designated as "Ada School" (after the

legendary donor of one of its principal manuscripts) but now

generally ascribed to the Court School.[186]

The motif appears

first in the Godescalc Gospels, the earliest richly illuminated

manuscript of the group, written and illuminated

by the monk Godescalc (781-783) upon the request of

Charlemagne (fig. 18).[187]

There one also finds its classical

prototype form (fig. 19). It reappears in the canon arches

of the Ada Gospels, written around 800 by a certain "Ada

Ancilla Dei," reputed to have been a sister of Charlemagne

(fig. 20).[188]

It is found again in the canon arches of the

Harley Gospels (fig 21),[189]

and the Gospels of St. Medard de

Soissons,[190]

both from the beginning of the ninth century,

as well as in various places of the Lorsch Gospels (figs. 22

and 23), one of the latest and most illustrious manuscripts

of the Court School, written and illuminated around 810,

presumably upon the request of Charlemagne (now in

part in Alba Julia, Roumania, Bibliotheca Documentara

Batthyaneum; in part in the Vatican Library, Pal. lat. 50).[191]

The motif does not appear to be common to any of the

other major schools of the period.[192]

I am tempted to

ascribe the drawing of the prototype plan to a man who

was trained in the tradition of the Court School. For

reasons already given, this man must have worked in close

association with Bishop Hildebold of Cologne, who as

sacri palatii arcicapellanus (a title which he held from

791 to the day of his death in 819) continued to remain,

even under the reign of Louis the Pious, the highest

ranking churchman in the empire. More evidence in favor

of the supposition that the original scheme of the Plan was

developed by someone close to the imperial court is to be

found in the striking similarities between the geometrical

square-grid pattern used in the dimensional layout of the

Plan with those which were employed, almost two decades

earlier, in the layout of the palace grounds at Aachen.[193]

There is no reason to assume that the scheme of the

prototype plan differed in any appreciable manner from

that of the copy. The very fact that the copy was made by

tracing precludes this. Even the textual annotations must

have been an integral part of the original, since without

them, the purpose of a great number of buildings of

virtually identical design would have remained incomprehensible.[194]

Clearly not part of the original plan, of course,

were the letter of transmission and the inscription of the

main altar of the Church, which relate to the specific

purpose of the copy.[195]

[ILLUSTRATION]

23. LORSCH GOSPELS

BUCHAREST, National Library (formerly Alba Julia, Roumania), fol. 10v

ca. 810

[after Braunfels, 1967, 20]

Detail of the fifth canon arch.

The churchman in charge of the technical and aesthetic execution of the prototype plan (816-817) was trained at the so called "Court

School"—a scriptorium that flourished in the emperor's entourage. It produced a magnificent series of sumptuously illustrated manuscripts in

which decorative motifs of the preceding Hiberno-Saxon school of illumination (7th and 8th centuries) fused with classical tradition under the

influence of a new group of Romano-Christian and Romano-Byzantine manuscripts that must have found their way to the emperor's court.

The Godescalc Gospels is the earliest known manuscript of this school. It was executed between 771 and 773, at Charlemagne's request, by the

scribe Godescalc, a member of the emperor's following.

The illustrious manuscripts produced by the Court School during the next four decades included the Ada Gospels, the Harley Gospels, and the

Gospels of St. Medard. The work of the school reached an aesthetic height in the Lorsch Gospels. Written and illuminated around 810, and

kept during the Middle Ages in the monastery of Lorsch, it was done entirely in gold and includes, besides the twelve canon arches, portraits of

the four evangelists and a striking image of Christ in Majesty at the beginning of Matthew.

At some unknown time after the Middle Ages, the Lorsch Gospels were separated into two parts. The Gospels of Mark and Matthew, were

transmitted to the Biblioteca Documentaria Bathyaneum and were eventually moved to the National Library, Bucharest; the Gospels of Luke

and John came to be held by the Vatican Library.

At the Council of Europe exhibition, KARL DER GROSSE (Aachen, 1965), the two parts of the Lorsch Gospels were re-united for the first time

in centuries, and subsequently published in a superb facsimile edition, under the editorship of Wolfgang Braunfels.

The union between classical illusionism and northern linearism that characterizes the style of Court School manuscripts has its parallel in

architecture in the modular reorganization of the monolithic spaces of the Early Christian basilica, the nature and cultural significance of

which is analyzed below in our discussion of square schematism (pp. 221ff).