The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| I. 1. |

| I.1.1. |

| I.1.2. |

| I.1.3. |

| I.1.4. |

| I.1.5. |

| I.1.6. |

| I.1.7. |

| I. 2. |

| I.2.1. |

| I. 3. |

| I.3.1. |

| I.3.2. |

| I.3.3. |

| I. 4. |

| I.4.1. |

| I.4.2. |

| I. 5. |

| I.5.1. |

| I.5.2. |

| I.5.3. |

| I. 6. |

| I.6.1. |

| I. 7. |

| I.7.1. |

| I.7.2. |

| I.7.3. |

| I.7.4. |

| I. 8. |

| I. 9. |

| I.9.1. |

| I. 10. |

| I.10.1. |

| I.10.2. |

| I. 11. |

| I.11.1. |

| I.11.2. |

| I. 12. |

| I.12.1. |

| I.12.2. |

| I.12.3. |

| I.12.4. |

| I.12.5. |

| I.12.6. |

| I.12.7. |

| I. 13. |

| I.13.1. |

| I.13.2. |

| I.13.3. |

| I.13.4. |

| I.13.5. |

| I.13.6. |

| I.13.7. |

| I.13.8. |

| I. 14. |

| I.14.1. |

| I.14.2. |

| I.14.3. |

| I.14.4. |

| I.14.5. |

| I.14.6. |

| I.14.7. |

| I.14.8. |

| I.14.9. |

| I. 15. |

| I.15.1. |

| I. 16. |

| I. 17. |

| II. |

| II. 1. |

| II.1.1. |

| II.1.2. |

| II.1.3. |

| II.1.4. |

| II.1.5. |

| II.1.6. |

| II.1.7. |

| II.1.8. |

| II.1.9. |

| II.1.10. |

| II.1.11. |

| II.1.12. |

| II.1.13. |

| II. 2. |

| II.2.1. |

| II.2.2. |

| II. 3. |

| II.3.1. |

| II.3.2. |

| II.3.3. |

| II.3.4. |

| II.3.5. |

| II.3.6. |

| II.3.7. |

| II.3.8. |

| II.3.9. |

| II.3.10. |

| III. |

| III. 1. |

| III.1.1. |

| III.1.2. |

| III.1.3. |

| III.1.4. |

| III.1.5. |

| III.1.6. |

| III.1.7. |

| III.1.8. |

| III.1.9. |

| III.1.30. |

The probable daily allowance of wine at the time

The Plan of St. Gall was drawn |

| III.1.11. |

| III. 2. |

| III.2.1. |

| III.2.2. |

| III.2.3. |

| III.2.4. |

| III.2.5. |

| III.2.6. |

| III.2.7. |

| III.2.8. |

| III. 3. |

| III.3.1. |

| III.3.2. |

| III.3.3. |

| III.3.4. |

| III.3.5. |

| IV. |

| IV. 1. |

| IV.1.1. |

| IV.1.2. |

| IV.1.3. |

| IV.1.4. |

| IV.1.5. |

| IV.1.6. |

| IV.1.7. |

| IV.1.8. |

| IV.1.9. |

| IV.1.10. |

| IV.1.11. |

| IV.1.12. |

| IV. 2. |

| IV.2.1. |

| IV.2.2. |

| IV.2.3. |

| IV. 3. |

| IV.3.1. |

| IV. 4. |

| IV.4.1. |

| IV.4.2. |

| IV. 5. |

| IV.5.1. |

| IV. 6. |

| IV.6.1. |

| IV. 7. |

| IV.7.1. |

| IV.7.2. |

| IV.7.3. |

| IV.7.4. |

| IV.7.5. |

| IV.7.6. |

| IV.7.7. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

The probable daily allowance of wine at the time

The Plan of St. Gall was drawn

The hemina that St. Benedict had in mind probably

came closer to that which was in use under the Romans in

classical times than to any of the later Frankish measures.

This would have entitled the monks to drink a little over a

fourth and perhaps as much as a third of a liter of wine

per day. Whether taken in the course of a single meal or

spaced out over two meals, this amount could hardly have

had any damaging effects on health or have lead to "surfeit"

or "drunkeness," especially not if these meals were

followed, as they traditionally were, by either a brief

period of rest,[238]

or by sleep.[239]

St. Benedict's assessment

of the quantity of wine that could be safely consumed at

the monks' table was both conservative and judicious. But

in evaluating his ruling historically one must not lose

sight of the fact that when St. Benedict took the epochal

step of sanctioning the consumption of wine for the

monastic community, the issue was as yet a highly controversial

one. Once the decision was made, the frailties of

human nature would tend to push the allowance upward.

From 0.2736 liters to 0.5 liters is not a big step; the less so,

if one considers the great inflation the hemina experienced

as an official capacity measure between the time of St.

Benedict and the time of Louis the Pious. That the daily

monastic allowance would follow this inflationary cycle,

which peaked under Louis the Pious to the impressive

equivalent of 2.12 liters, is impossible to assume. That it

rose to 0.5 liters is probable. There are even some indications

that it might have risen as high as 0.7 liters. A half-liter

of wine per day, if consumed by a healthy man in the

course of two successive meals, could still be interpreted as

lying within the spirit of St. Benedict's ruling; 0.7 liters

would have pushed the Rule to its limit; any amount above

that would have been clearly in violation of the Rule.[240]

My suspicion that the daily allowance of wine might have

risen as high as 0.7 liters at the time of Louis the Pious is

based upon a well known but perhaps not fully explored

passage in the Customs of Corbie, where we are told that in

this monastery each visiting pauper was issued two

245. BOOK OF KELLS. DUBLIN, TRINITY COLLEGE LIBRARY. MS 59, fol. 188r

OPENING WORDS OF ST. MARK GOSPELS

[by courtesy of the Trustees of Trinity College]

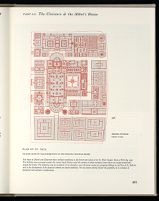

246. PLAN OF ST. GALL

DIAGRAM SHOWING THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE PRINCIPAL BUILDING MASSES

The shape of Church and Claustrum bears striking resemblance to the Quoniam initial of the St. Mark Gospels, Book of Kells (fig. 245).

The building masses grouped around this central motif likewise recall the manner in which secondary letter blocks are ranged peripherally

around the initial. The similarity may be accidental, if not deceptive, since the prime reasons for grouping buildings on the Plan of St. Gall (as

well as the development of the claustral scheme) are clearly funtional. Yet one cannot entirely discard the possibility of an interplay of

functional with aesthetic considerations.

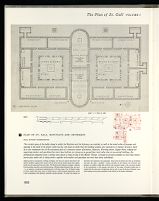

247. PLAN OF ST. GALL. NOVITIATE AND INFIRMARY

PLAN. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

The circular apses of the double chapel to which the Novitiate and the Infirmary are attached, as well as the round arches of passages and

openings in the walls of the cloister walks (see fig. 236) leave no doubt that this building complex was conceived as a masonry structure. Each

of its two components has all the constituent parts of a monastic cloister (Dormitory, Refectory, Warming Room, Supply Room, lodgings for

supervising teachers and guardians) but since these facilities are strung out on ground floor level rather than in two-storied buildings, this

architectural compound covers a surface area almost as large as that of the Monks' Cloister. It housed in practice probably no more than twelve

novices plus twelve sick or dying monks—together with teachers and guardians not more than thirty individuals.

Differing dietary prerogatives, bathing privileges, and need for special educational and

medical facilities, required that novices and the ill not only be housed apart from regular

monks, but also separated from each other. The Novitiate and Infirmary complex—inspired

by the grandiose centrality and axial bisymmetry of Roman imperial palaces (figs. 240-242)

—is an ingenious architectural implementation of all these needs. Two U-shaped ranges

of rooms around open inner courts, on either side of a church halved transversely, served

a dual constituency with identical, mutually isolated facilities. No doubt the location of

Novitiate and Infirmary was purposeful. Away from the bustle and noise of workshops

and near the open, "parklike" eastern paradise of the Church, the Orchard, and

gardens, its residents might find activities and recreation suited to the returning strength

of the convalescent, or the energies and spirits of the young. Proximity might serve to

remind both ill and novices of beginnings and an end, in view of the great Cemetery cross,

while healing and learning continued in the embrace of the larger community.

passage discloses that the "beaker" of Corbie was capable

of holding 1/96 of a modius[241] which in the light of the

values established by M. B. Guérard for capacity measures

in use at the time when this text was written (A.D. 822)

would amount to 0.7 liters.[242] The passage does not refer

to wine but to beer; however, the relative value of wine

and beer had been defined in 816 in the first synod of

Aachen, in a chapter which directed that if a shortage of

wine were to occur in a monastery, the traditional measure

of wine should be replaced by twice that volume of beer:

ubi autem uinum non est unde hemina detur duplicem eminae

mensuram de ceruisa bona . . . accipiant.[243] This directive was

promulgated as an imperial law and must have been known

to everyone in the empire.

Truly enough the Customs of Corbie speak of rations to

be issued to the poor, not to the monks, but since from

another chapter of that same text it can be inferred that

monks and paupers are entitled to the same ration of

bread,[244]

there is more than a high probability that they

were also granted the same ration of wine or beer. Good

monastic custom would require that an equal amount be

also granted to the serfs. The latter might even have been

issued slightly larger rations because of their involvement

in hard physical labor.

After the evening meal, which was succeeded only by a brief period

of reading and by Compline. See Benedicti regula, chap. 42; ed. Hanslik

1960, 104; ed. McCann, 1952, 100-101; ed. Steidle, 1952, 240-41.

The effect of wine or beer on man depends on the concentration of

alcohol in the blood, and this in turn is dependent on the manner in

which the intake is spaced out over the day and to what extent the

alcohol is diluted by food. Dr. Alfred Childs, an expert on alcohol in the

School of Public Health of the University of California at Berkeley,

advises me that half a liter of wine, spaced out over two meals, and

allowing for some rest after the midday meal, would not have any

damaging effects although it might well involve some temporary impairment

of cerebration during earlier phases of the period during which the

alcohol is metabolized. Even 0.7 liters, if spaced out over two meals and

diluted by food, Dr. Childs opines, might still be within the safety limits

set by St. Benedict (i.e., neither lead to "surfeit" nor "drunkeness")

but would be pushing it close to the edge of these limits. For an analysis

of the metabolism of alcohol, the mechanism of its toxic effects and its

rational use by healthy persons, see Childs, 1970.

Consuetudines Corbeienses, chap. 4; ed. Semmler, Corp. con. mon., I

1963, 373; and Jones, III, Appendix II, 105; where it is stipulated that a

quarter of a modius or four sesters of beer be divided daily among twelve

paupers, "so that each will receive two beakers." From this it must be

inferred that there were 96 beakers in a modius (I do not see how Semmler

arrived at the figure of seventy-two. Semmler, 1963, 54). Since in 822

when the Customs of Corbie was written, the official capacity of the

modius was 68 liters, the beaker of Corbie must have been the equivalent

of 0.7 liters. The directive reads as follows: De potu autem detur cotidie

modius dimidius, id sunt sextarii octo, de quibus diuiduntur sextarii quattuor

inter illos duodecim suprasriptos, ita ut unusquisque accipiat calices duos.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||