The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| I. 1. |

| I.1.1. |

| I.1.2. |

| I.1.3. |

| I.1.4. |

| I.1.5. |

| I.1.6. |

| I.1.7. |

| I. 2. |

| I.2.1. |

| I. 3. |

| I.3.1. |

| I.3.2. |

| I.3.3. |

| I. 4. |

| I.4.1. |

| I.4.2. |

| I. 5. |

| I.5.1. |

| I.5.2. |

| I.5.3. |

| I. 6. |

| I.6.1. |

| I. 7. |

| I.7.1. |

| I.7.2. |

| I.7.3. |

| I.7.4. |

| I. 8. |

| I. 9. |

| I.9.1. |

| I. 10. |

| I.10.1. |

| I.10.2. |

| I. 11. |

| I.11.1. |

| I.11.2. |

| I. 12. |

| I.12.1. |

| I.12.2. |

| I.12.3. |

| I.12.4. |

| I.12.5. |

| I.12.6. |

| I.12.7. |

| I. 13. |

| I.13.1. |

| I.13.2. |

| I.13.3. |

| I.13.4. |

| I.13.5. |

| I.13.6. |

| I.13.7. |

| I.13.8. |

| I. 14. |

| I.14.1. |

| I.14.2. |

| I.14.3. |

| I.14.4. |

| I.14.5. |

| I.14.6. |

| I.14.7. |

| I.14.8. |

| I.14.9. |

| I. 15. |

| I.15.1. |

| I. 16. |

| I. 17. |

| II. |

| II. 1. |

| II.1.1. |

| II.1.2. |

| II.1.3. |

| II.1.4. |

| II.1.5. |

| II.1.6. |

| II.1.7. |

| II.1.8. |

| II.1.9. |

| II.1.10. |

| II.1.11. |

| II.1.12. |

| II.1.13. |

| II. 2. |

| II.2.1. |

| II.2.2. |

| II. 3. |

| II.3.1. |

| II.3.2. |

| II.3.3. |

| II.3.4. |

| II.3.5. |

| II.3.6. | II.3.6 |

| II.3.7. |

| II.3.8. |

| II.3.9. |

| II.3.10. |

| III. |

| III. 1. |

| III.1.1. |

| III.1.2. |

| III.1.3. |

| III.1.4. |

| III.1.5. |

| III.1.6. |

| III.1.7. |

| III.1.8. |

| III.1.9. |

| III.1.30. |

| III.1.11. |

| III. 2. |

| III.2.1. |

| III.2.2. |

| III.2.3. |

| III.2.4. |

| III.2.5. |

| III.2.6. |

| III.2.7. |

| III.2.8. |

| III. 3. |

| III.3.1. |

| III.3.2. |

| III.3.3. |

| III.3.4. |

| III.3.5. |

| IV. |

| IV. 1. |

| IV.1.1. |

| IV.1.2. |

| IV.1.3. |

| IV.1.4. |

| IV.1.5. |

| IV.1.6. |

| IV.1.7. |

| IV.1.8. |

| IV.1.9. |

| IV.1.10. |

| IV.1.11. |

| IV.1.12. |

| IV. 2. |

| IV.2.1. |

| IV.2.2. |

| IV.2.3. |

| IV. 3. |

| IV.3.1. |

| IV. 4. |

| IV.4.1. |

| IV.4.2. |

| IV. 5. |

| IV.5.1. |

| IV. 6. |

| IV.6.1. |

| IV. 7. |

| IV.7.1. |

| IV.7.2. |

| IV.7.3. |

| IV.7.4. |

| IV.7.5. |

| IV.7.6. |

| IV.7.7. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

II.3.6

COUNTER APSE

The counter apse is not a Carolingian invention. Basilicas

with apses at either end of the nave were in use in Early

Christian times,[254]

but appear to have been confined almost

exclusively to the North African provinces of Rome, where

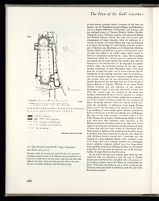

160. ST.-MAURICE-D'AGAUNE, Valais, Switzerland

[after Blondel, 1948, 29, fig. 5]

The plan renders the terminal form (end, 8th cent.) of a succession

of basilicas erected in honor of St. Maurice and his companions in a

monastery founded late in the 4th century under the crag where they

suffered martyrdom. Three preceeding churches, built on the same

site, were of smaller dimensions; each had only one apse.

known: two in Tripolitania (Lepcis Magna and Sabratha);

three in Algeria (Matifou, Orléansville, and Tipasa); and

six, perhaps seven, in Tunisia (Sbeitla, Haïdra, Henchir

Chigarnia, Iunca, Thelepte, and less well-excavated Mididi

and Henchir Goraat ez-Zid). The apse and counter apse

arrangement of these churches owes its existence to a

variety of reasons. At Lepcis Magna (fig. 159) and Sabratha

it is clearly the heritage of a pre-existing judiciary basilica

put to Christian use. Elsewhere, as at Orléansville, Matifou,

Tipasa, Sbeitla and Haïdra, a square or semicircular counter

apse was added to an earlier single apsed church to

serve as a sepulchral martyrion for a saint, whose growing

importance called for a second place of veneration within

the church. In still other places, the counter apse owed its

existence to the reorientation of an originally occidented

church, when the eastward location of the altar space

became mandatory in early Byzantine times. One cause

does not exclude the other and in some churches the reorientation

of the building coincided with the transformation

of the original apse into a funerary chapel, while the

new counter apse and the area immediately in front of it

became the site for the new high altar (as in the church of

Bishop Bellator at Sbeitla). Whether or not these North

African churches had any influence on the medieval

development is hard to say; but that much is sure, that

when the counter apse was adopted in the north and

became a traditional feature, it was in response to a sharply

rising interest in the cult of relics calling for an augmentation

of the number of stations needed for the veneration of

saints. In purely aesthetic terms one cannot entirely preclude

the possibility of influences from pagan Roman

times, even at this late stage of the adoption of the theme.

I am thinking of such double-apsed judiciary basilicas as

those on the forum of the Romano-British city of Silchester

(fig. 202) or the more recently excavated basilica of the

Gallo-Roman city of Augst in Switzerland. Basilicas of this

type must have been infinitely more numerous in the

Roman provincial territories north of the Alps than would

appear in present-day perspective and the remains of many

of them may still have been visible in Carolingian times.

Their power to influence the medieval development would

doubtlessly have been enhanced by the fact that when the

early Christian basilica entered into a symbiosis with the

concept of a large galleried cloister court, attached to one

of its long sides—as it became standard in Carolingian

times—aesthetic emphasis shifted from the longitudinal

directionalism of the early Christian basilica, to a broadside

orientation that had been an essential trait of the judiciary

basilica of pagan Rome in the first place.

In the north the apse and counter apse motif was not

employed with any consistency until the time of Charlemagne

and its introduction coincided with a renaissance of

the basilican design created for Rome by Constantine the

Great. The fusion established a norm which continued into

Ottonian times and lasted in Germany until the end of the

Romanesque period.

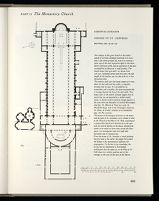

161. CORINTH-LECHAION

CHURCH OF ST. LEONIDAS

[after Pallas, 1962, 142, fig. 142]

The remains of this great church in the harbor

suburb of Corinth, although preserved to no more

than 2 feet above ground are, even in so ruinous a

state, one of the most impressive sights in the entire

Early Christian world, and an expression of the most

accomplished architecture it could produce. The

church dates from 450-460?; its atrium from

518-527. Including atrium and fore court, the full

length of this basilica was 610 feet (186 m. or 600

Byzantine feet).

The basilica itself (450 feet long) consists of a nave

about 60 feet wide and two aisles, a tripartite

transept and an apse. It is preceded by an

exonarthex and a narthex, the latter projecting like

a transept beyond the line of the aisle walls. Four

heavy piers in the eastern transept suggest that its

center bay was surmounted by a timber-roofed

tower—a feature which curiously enough appears at

the same time and thereafter in several Merovingian

churches: St. Martin at Tours (ca. 450), St.

Wandrille (647), and in the Carolingian church of

St. Denis, if Crosby's analysis of its foundations

(fig. 166.X) is correct.

The layout of the liturgical furniture in the BEMA

and the apse of St. Leonidas is very similar to that

in the Church of the Plan of St. Gall, consisting of

a semicircular bench (SYNTHRONON) in the apse

and two lateral benches in the BEMA, allowing the

monks to be seated on three sides around the altar

space—an arrangement that lent itself with

particular ease to monastic use.

From the BEMA of St. Leonidas a raised pathway

(SOLEA) lead to the AMBO, the pulpit from which

the bishop or his representative addresses the

congregation. To the best of my knowledge, the

SOLEA has no counterpart in Carolingian

architecture, but the AMBO is, on the Plan of St.

Gall shown in a similar position west of the

transept, in the axis of the nave of the church.

162. RAVENNA. CHURCH OF SAN VITALE

[after Encyclopedia dell' Arte Antiqua IV, Rome, 1965, 630, fig. 730]

San Vitale dates ca. 532-546. The two detached circular towers are

entered from the narthex. They give access to the gallery of the

church, an area reserved for women attending religious services.

Despite their clearly functional role, even at this early period they

may have had strong symbolic overtones as towers of the fortress of

God. At what point in history they came to be used as bell towers

is not easily ascertained (see above, pp. 129ff).

Probably because of their failure to fill practical needs, the detached

towers of the Church of the Plan of St. Gall had no consequence for

later medieval planning. Single detached towers, associated with

buildings of basilican plan may have been in use in the Exarchate of

Ravenna as early as the 8th century and became a common mark

of the Italian Romanesque and Gothic. North of the Alps, the

preferred solution was to incorporate the towers in the body of the

church—a process beginning with the invention of the Carolingian

Westwork (cf. pp. 206-208) and culminating in the medieval twin

tower façade. Even centrally planned buildings were affected by this

change, as witness the Palace Chapel at Aachen with its towers set

into an avant-corps with raised tribune from which the emperor

attended divine services (for changing stylistic concepts see caption to

Fig. 71.Z).

The oldest transalpine example known to date is the

basilica of St.-Maurice of Agaune, which dates from the

end of the eighth century (fig. 160). Then follow in

chronological order the abbey churches of Fulda, 802-819

(fig. 138); Paderborn, after 799; St. Willibrord in Echternach,

at the beginning of the ninth century; the Carolingian

cathedral of Cologne, traditionally ascribed to Archbishop

Hildebold, who died in 819 (fig. 139); St Remi, at Reims,

consecrated in 852; Auxerre Cathedral, 857-873; and the

Abbey Church at Oberzell on Reichenau, ca. 890.[255]

Liturgically, the counter apse provided a new sanctuary

for the founding saint of the monastery, who had in many

instances become more important in the ritual of the

church than its patron saint. In Fulda (fig. 138), we learn

from the Vita Eigilis the monumental west choir was added

under Abbot Ratger (802-819) to the church of Abbot

Baugulf (790/92-802) as a shrine to St. Boniface because of

the heightened veneration for the relics of the founding

saint.[256]

Louis Blondel's excavations of the monastery of

St.-Maurice of Agaune (fig. 160) have shown how a new

church with a counter apse allowed the relics of saints

previously venerated in separate buildings to be housed

together in one church.[257]

In churches with west-works, the

monumental western avant-corps of the church served the

same purpose.[258]

The western counter apse had the further advantage of

establishing a close liturgical tie with Rome, as the creation

of a sanctuary at the western end of the church was in

imitation of Old St. Peter's in Rome (figs. 104, 141).

Further, the adoption of this motif marked a decisive

step in the breaking away of Carolingian architecture from

the directional layout of the Early Christian basilica.

Because it was built onto what had formerly served as

the principal entrance to the church, the counter apse

completely eliminated the concept of the traditional

basilican facade. The nave had previously been a great

congregational longhouse designed to channel the worshiping

crowd toward the altar (fig. 81). With the introduction of

the counter apse, the nave became rather a connecting spatial

link between two terminal masses, both of which drew the

worshiper's attention (figs. 55, 107, 109, 111, 112). The

purpose of the nave was changed further by the railing-off

163. WERDEN CASKET (FRAGMENT). LONDON, VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM.

[by courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum]

A reliquary chest of carved ivory, the so-called Werden Casket, formerly believed to date to the beginning of the 5th century, was recently declared

a Carolingian copy (Beckwith, 1958, 1-11). The detail here shows Mary and Anne in the Visitation scene, and to their side the city of Judah,

represented by a building terminating in an apse and flanked by two detached circular towers.

If the Early Christian model of this carving reflects actual building practice, the ivory would bear witness to the existence in Late Antiquity of

detached circular towers flanking a church. So far, there appears to be no tangible archaeological evidence to confirm this conjecture except for the

staircase towers of the church of San Vitale, Ravenna (fig. 162).

164. PLAN OF ST. GALL. ALTAR ARRANGEMENT

| 1. | SS Mary and Gall |

| 2. | Holy Cross |

| 3. | SS John the Baptist and John the Evangelist |

| 4. | St. Paul |

| 5. | St. Peter |

| 6. | SS Philip and James |

| 7. | St. Andrew |

| 8. | St. Benedict |

| 9. | St. Columba |

| 10. | St. Stephen |

| 11. | St. Lawrence |

| 12. | St. Martin |

| 13. | St. Mauritius |

| 14. | Holy Innocents |

| 15. | St. Sebastian |

| 16. | SS Lucia and Cecilia |

| 17. | SS Agatha and Agnes |

| 18. | St. Gabriel |

| 19. | St. Michael |

For a descriptive analysis of the altars and their identifying titles, see pp.

129-44. The schema shown above does not include altars in the chapels of the

Novitiate and Infirmary, whose patronage is not designated on the Plan (see

fig. 247, p. 302 and p. 311). A total of twenty-one altars is shown on the Plan.

On the number symbolism embedded in this figure and the distribution of altars

within the church see fig. 80.X, p. 124. On the importance of the layout of the

altars in reflecting and stimulating the emergence within the Church of a new

principle of spatial division distinctly different from the spatial directionalism of

Early Christian churches, see pp. 127-28 and caption to fig. 165.

leaving only the center of the nave accessible to laymen (figs.

82 and 110). This was the monastic Carolingian response

to the large congregational halls of the age of Constantine.

This architectural change reflects a liturgical one. The

great basilican churches of Constantine had been designed

for large crowds of worshipers, most of whom had only

recently been converted to the new faith. By contrast, the

Carolingian monastery church was designed for the worship

of a small community of men who lived in seclusion. In the

Early Christian basilica the body of officiating priests was

relatively small, the size of the attending crowd, colossal.

In the Carolingian monastery church, the number of

worshiping monks was relatively large (an average of 100 to

150; 300 to 400 in unusual cases), that of the attending

laymen not significantly larger. During the great religious

festivals, and in particular the feast of the patron saint, the

throng of pilgrims could rise to enormous numbers; but for

the rest of the year the lay attendance in the church remained

confined to the serfs who worked within the

monastic enclosure (in general outnumbering the monks

by not more than 30 per cent)[259]

plus the tenants who lived

in cottages or on farms immediately around the abbey.

An excellent recent summary of the history of the counter apse will

be found in Thümmler, 1960, col. 93. Of earlier literature to be consulted

on this problem, see Dehio and von Bezold, I, 1892, 167ff;

Effmann, 1912, 153ff; Braun, I 1924, 388ff; Arens, 1938, 61, n. 89;

Doppelfeld, 1954, 50ff; Schmidt, 1956, 403ff. On Early Christian

basilicas with apse and counter apse in Tunisia, see Lapeyre, 1940,

180-81; in Tripolitania see Romanelli, 1940, 246; in Spain see Durliat,

1966, 42 fig. 9, and Hubert, 1966, 42 fig. 9.

Brief summaries on North African churches of the fifth and sixth

centuries with apse and counter apse will be found in Ward Perkins,

1965, 62-63 (Lepcis Magna I, ibid., 22-34; Sabratha I, ibid. 7-19) and

N. Duval, 1965, 472-78 (Sbeitla and Haïdra). Krautheimer, 1962, 22-23,

in a discussion of Orléansville, disclaims the possibility of any influence

of these North African churches on the medieval development: "But

counter apses remain rare and contrary to older opinions, are not the

immediate sources for those of medieval churches in Europe."

On the basilica of Silchester, see J. G. Joyce, 1881, 344-65 and below,

p. 256. On the basilica of Augst, see Reinle, 1965, 34 and below, p. 200.

I am following Thümmler's enumeration, loc. cit. For St. Maurice

of Agaune, see Blondel, 1948, 9-57, and 1957, 283-92; for Fulda, see

Beumann and Grossmann, 1949, 17-56; for Paderborn, Thümmler,

1957, 87ff; for Echternach, Meyers, 1951, 1ff; for Cologne, Doppelfeld,

1948, 1954, 1958; for Reims, Hubert, 1938, 30; for Auxerre, Louis, 1952;

for Oberzell, Hecht, I, 1928, 132ff, Christ, 1956, and Gall, 1956.

Excellent summaries of the state of knowledge concerning the German

churches here cited will be found in Vorromanische Kirchenbauten,

F. Oswald, L. Schaefer and H. R. Sennhauser, editors, 1966-1968, where

these buildings are dealt with in alphabetical order.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||