I.14.8

CONCLUSIONS

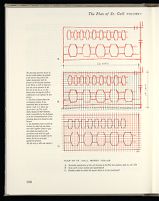

The foregoing analysis of the construction methods employed

in the Plan of St. Gall should dispel, once and for

all, the widespread belief that medieval architectural drawings

were not made "to scale."[379]

In contradiction to traditionally

prevailing views—but in confirmation of certain

observations made by Boeckelmann and Arens—this

analysis demonstrates that the author of the original scheme

of the Plan availed himself not only of a clearly definable

scale, but that he applied this scale throughout the entire

layout of the Plan with full consistency and logic.

From the methods employed in modern scale construction

the Plan of St. Gall differs neither in the logic of its

graduations, nor in the truthfulness with which this

graduation reflects the variations of the rendered object.

From the methods of modern scale construction the Plan

of St. Gall differs in two points only: first, in the fact that

it flows from a basically modular type of thinking; and

second, that its basic working units are derived as fractions

or multiples from a dimensional master value.

If a modern architect assigns to a given area a value of

40 feet, he does so with the aid of a ruler, on which the

value 40 is graduated into forty equal parts of one. On the

scale of the Plan of St. Gall, quite differently, the magnitude

40, as is found, was not subdivided into forty units of one,

but into sixteen units of 2½. Why the author of the Plan of

St. Gall divided his 40-foot scale into 16 units of 2½ rather

than into 40 units of one must by necessity remain a matter

for speculation. The value 2½, as my colleague Hunter

Dupree points out to me, was a fundamental unit of the

English surveying system. Two and one-half feet is the

length of the English pace (the space traversed by one

step).[380]

Could it be that the 2½-foot standard module of the

Plan of St. Gall was the equivalent of a traditional and

widely used Carolingian pace? And that the superordinate

modules of 40- and 160-foot squares were calculated as

meaningful multiples of that pace? There are other

historical factors which may have contributed to the

genesis of such relationships. To subdivide a primary value

of 40 into sixteen equal fractions (or to arrive at that value

by multiplying sixteen times a primary value of 2½) as has

been pointed out on the preceding pages, is one of the

easiest and, for that reason, also the oldest operations of

the human mind, requiring no other instrument than a

straightedge and a compass (method of continuous halving

or doubling). In chosing this procedure, the draftsman may

also have been influenced by the eminently sacred connotations

associated in his day with the two basic figures used

in this operation, the figures 40 and 4.

The choice of the figure 40 for the width of the nave can

hardly be considered an accident. Forty was a number

which in Biblical tradition had been associated for ages

with periods of expectation and penitence. Forty were the

days of the great primeval deluge, forty the years that the

Hebrews spent in the desert, forty the days that Moses

passed in expectation on Mount Sinai, forty the days

announced by Jonah for the destruction of the city of

Nineveh, forty the days that separated the Ascension from

the Resurrection.[381]

Forty, it should be noted, is not only

the width attributed on the Plan of St. Gall to the nave and

the transept, but also the total number of buildings of

which the monastery is composed.

In halving this sacred figure four times in succession, the

draftsman put into operation another eminently sacred

figure, associated both in the pagan and the Christian

tradition with the basic divisions of matter, time, and

space: the four elements, the four seasons, the four rivers

of Paradise, the four cardinal virtues, the four main

prophets, the four evangelists.

Whatever his reasons may have been (and I shall say

more about the number symbolism of the Plan a little later)

in organizing the layout of his monastery in a manner in

which all values could be expressed as multiples of 40 or as

multiples of a fraction obtained by halving 40 four times,

the draftsman provided his plan with a scale that could be

read and applied by anybody who was familiar with the

principles involved or who knew the formula. It is due to

the relative largeness of its standard unit (2½ feet) that the

Plan owes its easy readability, and that it could be traced

upon another sheet of parchment without sustaining any

serious loss in clarity and measurability.

The development of a modular grid in which all superand

subordinate units are derived in logical steps of progression

or diminution from the dimensions of a controlling

master module was an intellectual achievement of the

highest order and a concept that was tragically corrupted

when—(I presume at the second synod of Aachen, as the

Plan was formally considered for adoption

[383]

)—it was decided

that the length of the church should be reduced from

300 feet (as shown in the drawing) to 200 feet (as stipulated

in the axial title of the church) and that the interstices of

the arcades should be reduced from 20 feet (as shown in

the drawing) to 12 feet (as stipulated in the title inscribed

into the arcades). Like the number 40, the number 12

belongs to a traditional repertoire of sacred figures that

formed a common currency of metaphor and analogy (the

twelve Judaic tribes, the twelve apostles, the twelve months

of the year, the twelve hours of the day, et cetera),

[384]

that

could be put into circulation on even the most precipitate

call. But in contrast to 40, 12 as a dimension is not part of

the modular grid of the Plan. Being neither a multiple nor

a fraction of 40, it is clearly a foreign body in this system.

In introducing this figure for a feature aesthetically as

prominent as the arcades of the nave, the churchmen who

prescribed this change demolished one of the most precious

and most innovative aspects of the Plan: its square schematism.

It is probable that we will never be able to establish

who they were, these men,

[385]

yet one thing is certain: they

could not, in any manner, have been involved in the design

process that went into the making of the original scheme—

and they were worlds removed from understanding its

unusual aesthetic merits. To shorten the church by 100 feet

did not in itself require abandoning the modular scheme.

It could have been done in increments of its own control

module by the simple elimination of five 20-foot bays in

the nave. But the stipulation that the interstices of the

arcades be reduced from 20 to 12 feet forestalled any such

possibility and effectively destroyed the system of squares

in the church. The change was drastic, and, had it been

implemented in the drawing, would have required the

preparation of an entirely new Plan.

We are faced here with a manifestation of the age-old

conflict between architectural creativity and administrative

control, with disastrous consequences for the former when

the latter unwittingly becomes involved in the design process

with decisions which, though not necessarily arbitrary,

are nevertheless extraneous to the creative act and innocent

of any knowledge of technical detail and planning.

The author of the original scheme, if he was present at

the gathering where these decisions were taken, must

have gone through moments of shattering pain. He had

produced a scheme of extraordinary conceptual subtleties

including the design of a church which, had it ever been

built, would have been one of the highlights of early

medieval architecture (fig. 110). It took two-and-one-half

centuries of further development in western architecture

before the ideas first conceived here were embodied in some

of the great Romanesque cathedrals of Europe.[386]