The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| I. 1. |

| I.1.1. |

| I.1.2. |

| I.1.3. |

| I.1.4. |

| I.1.5. |

| I.1.6. |

| I.1.7. |

| I. 2. |

| I.2.1. |

| I. 3. |

| I.3.1. |

| I.3.2. |

| I.3.3. |

| I. 4. |

| I.4.1. |

| I.4.2. |

| I. 5. |

| I.5.1. |

| I.5.2. |

| I.5.3. |

| I. 6. |

| I.6.1. |

| I. 7. |

| I.7.1. |

| I.7.2. |

| I.7.3. |

| I.7.4. |

| I. 8. |

| I. 9. |

| I.9.1. |

| I. 10. |

| I.10.1. |

| I.10.2. |

| I. 11. |

| I.11.1. |

| I.11.2. |

| I. 12. |

| I.12.1. |

| I.12.2. |

| I.12.3. |

| I.12.4. |

| I.12.5. |

| I.12.6. |

| I.12.7. |

| I. 13. |

| I.13.1. |

| I.13.2. |

| I.13.3. |

| I.13.4. |

| I.13.5. |

| I.13.6. |

| I.13.7. |

| I.13.8. |

| I. 14. |

| I.14.1. |

| I.14.2. |

| I.14.3. |

| I.14.4. |

| I.14.5. |

| I.14.6. |

| I.14.7. |

| I.14.8. |

| I.14.9. |

| I. 15. |

| I.15.1. |

| I. 16. |

| I. 17. |

| II. |

| II. 1. |

| II.1.1. |

| II.1.2. |

| II.1.3. |

| II.1.4. |

| II.1.5. |

| II.1.6. |

| II.1.7. |

| II.1.8. |

| II.1.9. |

| II.1.10. |

| II.1.11. |

| II.1.12. |

NUMBER OF SCRIBES & COLLABORATION |

| II.1.13. |

| II. 2. |

| II.2.1. |

| II.2.2. |

| II. 3. |

| II.3.1. |

| II.3.2. |

| II.3.3. |

| II.3.4. |

| II.3.5. |

| II.3.6. |

| II.3.7. |

| II.3.8. |

| II.3.9. |

| II.3.10. |

| III. |

| III. 1. |

| III.1.1. |

| III.1.2. |

| III.1.3. |

| III.1.4. |

| III.1.5. |

| III.1.6. |

| III.1.7. |

| III.1.8. |

| III.1.9. |

| III.1.30. |

| III.1.11. |

| III. 2. |

| III.2.1. |

| III.2.2. |

| III.2.3. |

| III.2.4. |

| III.2.5. |

| III.2.6. |

| III.2.7. |

| III.2.8. |

| III. 3. |

| III.3.1. |

| III.3.2. |

| III.3.3. |

| III.3.4. |

| III.3.5. |

| IV. |

| IV. 1. |

| IV.1.1. |

| IV.1.2. |

| IV.1.3. |

| IV.1.4. |

| IV.1.5. |

| IV.1.6. |

| IV.1.7. |

| IV.1.8. |

| IV.1.9. |

| IV.1.10. |

| IV.1.11. |

| IV.1.12. |

| IV. 2. |

| IV.2.1. |

| IV.2.2. |

| IV.2.3. |

| IV. 3. |

| IV.3.1. |

| IV. 4. |

| IV.4.1. |

| IV.4.2. |

| IV. 5. |

| IV.5.1. |

| IV. 6. |

| IV.6.1. |

| IV. 7. |

| IV.7.1. |

| IV.7.2. |

| IV.7.3. |

| IV.7.4. |

| IV.7.5. |

| IV.7.6. |

| IV.7.7. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

NUMBER OF SCRIBES & COLLABORATION

The number of monks who sat at work in the scriptorium

must have varied greatly. The layout of the Scriptorium on

the Plan of St. Gall would allow fourteen monks to write

simultaneously, if we assume that each writing desk was

manned by two scribes. Since there are ten feet of space

between each window, two scribes could have worked in

comfort at a single desk. But the total number of scribes at

work each day in the Scriptorium could have been considerably

increased if the scribes worked in shifts.

A. Bruckner, on the basis of an actual count of the hands

at work in individual manuscripts, has calculated that the

monastery of St. Gall, between 750 and 770, employed

some twenty-five scribes for copying manuscripts and

around fifteen more for writing documents—a total of

forty.[110]

Under Abbot Waldo and shortly after him (770790)

the number of scribes rose to about eighty;[111]

under

Abbot Gozbert (816-836) to about a hundred.[112]

Some of

these may have worked in carrels, in one of the cloister

walks, as was customary in Tournai in the eleventh

century[113]

and to be found later on in many other places.[114]

A codex was rarely written entirely by a single hand. At

the scriptorium of St. Martin's at Tours, in the first half of

the eighth century, more than twenty scribes collaborated

in a copy of Eugippius.[115]

The texts of other manuscripts

copied at that same school were written, variously, by five,

seven, eight, or twelve different hands.[116]

Fourteen scribes

listed by name in manuscripts of St. Martin appear in a

register drawn up in 820.[117]

ROMANESQUE CHURCH BENCH, MONASTERY OF ALPIRSBACH

100.

100.X

FORMERLY STUTTGART, SCHLOSSMUSEUM

(DESTROYED IN WW II.) After Falke, 1924, pl. 1

Although probably not antedating the thirteenth century, this medieval church bench with its simple carpentry embodies a type one

would expect to have been in use centuries earlier. The drafter of the Plan referred to this type of bench as FORMULA (see above

p. 137 and Glossary, III, s.v.). Four such benches, each with a seating capacity of not more than four people, would have been

set up in the crossing of the Church probably for use by a specially trained choir singing in antiphon.

HEXHAM, NORTHUMBERLAND, ENGLAND

NIGHT STAIRS, PRIORY CHURCH

Unquestionably one of the finest extant medieval night stairs, located in the southern transept arm, it leads directly from dormitory into church.

In general such stairs provided the only connection between dormitory and cloister. In the 12th and 13th centuries, they were invariably made of

stone; in earlier times perhaps of timber. Except for those in the Church, the author of the Plan of St. Gall omits stairs from it.

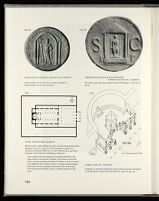

102.A GOD JANUS UNDER A CELESTIAL CANOPY

Roman medal of A.D. 187, more than twice original size

[after Gnecchi, II, 1912, pl. 84, fig. 5]

104. TYRE, PALESTINE (LEBANON)

Basilica built by Bishop Paulinus in A.D. 314. Reconstructed plan [after

Nussbaum, 1965, II, 24, fig. 1]. The reconstruction is based on a

description by Eusebius, History of the Church (X, 4, 44) where

the layout of Synthronon and Bema is referred to:

"after completing the great building he [Constantine] furnished it with

thrones high up, to accord with the dignity of the prelates, and also with

benches arranged conveniently throughout. In addition to all this, he placed

in the middle the Holy of Holies—the altar—excluding the general public

from this part too by surrounding it with wooden trellis-work wrought

by the craftsmen with exquisite artistry, a marvellous sight for all who

see it."

102.B EMPEROR DOMITIAN ENTHRONED

UNDER CELESTIAL CANOPY

Sestertius, nearly three times original size [after Mattingly, II, 1930, pl. 77,

fig. 9]

103. ROME. OLD ST. PETER'S

Presbytery, as rebuilt by Gregory the Great between 594-604. Drawing by

S. Rizzello [after Toynbee and Ward-Perkins, 1956, 215, fig. 22]

Bruckner, 1938, 17. Under Abbot Sturmi (744-779) the same

number, i.e., forty scribes, were constantly employed in the scriptorium

of Fulda. See Thompson, 1939, 51.

Of Tournai it is written "if you had gone into the cloister you

might in general have seen a dozen young monks sitting on chairs in

perfect silence, writing at tables, carefully and skillfully constructed (ita

ut si claustrum ingredereris, videres plerumque duo decim monachos juvenes

sedentes in cathedris et super tabulas diligenter et artificiose compositas cum

silentio scribentes)." See Wattenbach, 1896, 271-72. Whether claustrum

in the passage quoted above can be interpreted as "cloister walk" rather

than "claustral range of buildings" is subject to question: and this

matter as well as the evidence cited by Roover in support of the assumption

that in certain cloisters certain scribes performed their craft in the

open cloister walk (Note 104) requires careful re-examination.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||