The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| I. 1. |

| I.1.1. |

| I.1.2. |

| I.1.3. |

| I.1.4. |

| I.1.5. |

| I.1.6. |

| I.1.7. |

| I. 2. |

| I.2.1. |

| I. 3. |

| I.3.1. |

| I.3.2. |

| I.3.3. |

| I. 4. |

| I.4.1. |

| I.4.2. |

| I. 5. |

| I.5.1. |

| I.5.2. |

| I.5.3. |

| I. 6. |

| I.6.1. |

| I. 7. |

| I.7.1. |

| I.7.2. |

| I.7.3. |

| I.7.4. |

| I. 8. |

| I. 9. |

| I.9.1. |

| I. 10. |

| I.10.1. |

| I.10.2. |

| I. 11. |

| I.11.1. |

| I.11.2. |

| I. 12. |

| I.12.1. |

| I.12.2. |

| I.12.3. |

| I.12.4. |

| I.12.5. |

| I.12.6. |

| I.12.7. |

| I. 13. |

| I.13.1. |

| I.13.2. |

| I.13.3. |

| I.13.4. |

| I.13.5. |

| I.13.6. |

| I.13.7. |

| I.13.8. |

| I. 14. |

| I.14.1. |

| I.14.2. |

| I.14.3. |

| I.14.4. |

| I.14.5. |

| I.14.6. |

| I.14.7. |

| I.14.8. |

| I.14.9. |

| I. 15. |

| I.15.1. |

| I. 16. |

| I. 17. |

| II. |

| II. 1. |

| II.1.1. |

| II.1.2. |

| II.1.3. |

| II.1.4. |

| II.1.5. |

| II.1.6. |

| II.1.7. |

| II.1.8. |

| II.1.9. |

| II.1.10. |

| II.1.11. |

| II.1.12. |

| II.1.13. |

| II. 2. |

| II.2.1. |

| II.2.2. |

| II. 3. |

| II.3.1. |

| II.3.2. |

| II.3.3. |

| II.3.4. |

| II.3.5. |

| II.3.6. |

| II.3.7. |

| II.3.8. |

| II.3.9. |

| II.3.10. |

| III. |

| III. 1. |

| III.1.1. |

| III.1.2. |

| III.1.3. |

| III.1.4. |

| III.1.5. |

| III.1.6. |

| III.1.7. |

| III.1.8. |

| III.1.9. |

| III.1.30. | III.1.30 |

| III.1.11. |

| III. 2. |

| III.2.1. |

| III.2.2. |

| III.2.3. |

| III.2.4. |

| III.2.5. |

| III.2.6. |

| III.2.7. |

| III.2.8. |

| III. 3. |

| III.3.1. |

| III.3.2. |

| III.3.3. |

| III.3.4. |

| III.3.5. |

| IV. |

| IV. 1. |

| IV.1.1. |

| IV.1.2. |

| IV.1.3. |

| IV.1.4. |

| IV.1.5. |

| IV.1.6. |

| IV.1.7. |

| IV.1.8. |

| IV.1.9. |

| IV.1.10. |

| IV.1.11. |

| IV.1.12. |

| IV. 2. |

| IV.2.1. |

| IV.2.2. |

| IV.2.3. |

| IV. 3. |

| IV.3.1. |

| IV. 4. |

| IV.4.1. |

| IV.4.2. |

| IV. 5. |

| IV.5.1. |

| IV. 6. |

| IV.6.1. |

| IV. 7. |

| IV.7.1. |

| IV.7.2. |

| IV.7.3. |

| IV.7.4. |

| IV.7.5. |

| IV.7.6. |

| IV.7.7. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

III.1.30

CELLAR AND LARDER

The Cellar and Larder is contiguous to the western cloister

walk, whose inscription refers to these facilities (fig. 225)

with the hexameter:

Huic porticui potus quoq·cella coher &

To this porch is attached the cellar in which the drinks

are stored

The building is 87½ feet long and, like the Dormitory and

the Refectory, was probably meant to be 40 feet wide. The

line that defines its southern long wall is disturbed in its

course, probably because the draftsman wanted to avoid

the stitches of the seam that runs along the line where this

wall should be, had it been placed in its proper position.

Because of the overlapping margins of the two joining

sheets, the parchment is so thick along this line that it

would have been impossible for the scribe who traced the

copy, even under the most favorable light conditions, to

recognize the details of the prototype plan.

Cellar

LAYOUT, DESIGN, AND DIMENSIONS

OF CASKS

The Cellar occupies the ground floor of a double-storied

structure, the upper level of which contains the Larder and

other necessary supplies (Infra cellarium. Supra lardariū &

aliorū necessarioriu repositio). The Cellar is equipped with

two rows of barrels set on rails: five large ones (maiores

tunnae) and nine smaller ones (minores). The small barrels

are 10 feet long and have a maximum diameter of 5 feet.

Their staves, convex for most of the length of the barrel,

take a turn toward the concave as they reach the end of the

cask. The large barrels are 15 feet long and have a central

diameter of 10 feet. Their staves are convex for the entire

length of the vessel. The scribe does not distinguish which

size barrel was used for wine and which for beer. (My

colleague, Prof. M. A. Amerine, assures me that there is no

technical reason why the same barrel might not be used

successively for the storage of wine and of beer, except that

red wine deposits pigment in the wood of the cask which, if

the cask is then used for beer or white wine, tends to discolor

these liquids.) It is likely that the practice was followed

of decanting the contents of large wine casks into

smaller ones, as volume was reduced through evaporation

and consumption, in order to prevent the wine spoiling

from contact with air.

During the aging of wine, as modern enologists point

out,[213]

there is a constant loss of liquid (called "ullage")

through the wood of the cask in which the wine is stored, a

loss which will cause acetification of the wine if it is not

made up. To prevent this occurrence, accepted modern

practice requires that large containers of wine be refilled

periodically (a process in California wineries called "topping")

240.B TRIER. AULA OF IMPERIAL PALACE. PERSPECTIVE FROM SOUTHEAST

[by courtesy of the Laudesmuseum, Trier]

The narthex (its walls are no longer standing) was internally divided into an entrance hall projecting forward, and presumably also reaching

higher up than the two lateral arms, from which doors lead into the galleries of the two courts flanking the hall.

same vintage, a supply of which is stored in smaller casks

and demijohns. The Monks' Cellar on the Plan of St. Gall,

with its different sizes of barrels, would be perfectly

equipped to handle this problem and the layout may indeed

suggest that both operations, the topping of larger from

smaller casks, as well as the decanting of larger barrels into

several smaller ones, were practiced in the monastic wineries

of the ninth century.

Another reason for having a larger number of small barrels,

in addition to the big ones is that this made it possible

to store smaller quantities of wine, obtained from different

vinyards, in separate containers and thus to retain their

specific character.

THE BARRELS IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

An invention of the Celts

Recent research has shown that the practice of storing and

moving wine in wooden casks made its appearance in

Europe in the first century B.C. in the territory of the Celts

and of the Illyrians. Pliny the Elder (A.D. 23/24-79) states

that "in the neighborhood of the Alps people put [wine]

into wooden casks and closed these round with hoops."[214]

Edward Hyams in an intriguing, but poorly annotated,

book ascribes this invention to the Allobroges, a Celtic

tribe that lived in and around the valley of one of the

principal alpine tributaries of the Rhone river, the Isère

(modern Dauphinois) where wine was first grown north of

Italy.[215]

Strabo (64/63 B.C.-A.D. 21 at least) informs us that

KONZ (CONTIONACUM)

241.B PERSPECTIVE RECONSTRUCTION

[by courtesy of the Landesmuseum, Trier]

241.A PLAN 1:600

[by courtesy of the Landesmuseum, Trier]

A summer residence of the Roman emperors in Trier, on a plateau above the confluence of the Saar and Moselle rivers, the palace consisted

of a central heatable audience hall with apse—a much smaller replica of the great aula of Trier (fig. 240), plus two outer wings running

parallel to the audience hall and separated from it by two inner courts. The wings were used as living quarters and included a bath. The

grouping of the principal building masses, in their perfect bisymmetry, bears striking resemblance to the layout of the Novitiate and Infirmary

complex of the Plan of St. Gall, except that in the villa of Konz the open courts were not colonnaded.

οἴκων) were used to store wine in Cisalpine Gaul,[216] and

that the Illyrians brought their wine from Aquileia to

various markets in wooden casks in exchange for slaves,

cattle and hides.[217]

Pliny, Hist. Nat., book XIV, chap. 27, ed. Rackham (Loeb Classical

Library), Harvard Univ.-London, IV 1952, 272-73: circa Alpes ligneis

vasis [vinum] condunt circulisque cingunt.

See Edward Hyams' interesting discussion of this subject in

Dionysos, A Social History of the Wine Vine, New York, 1965, 164ff

(a book brought to my attention by my colleague William B. Fretter, to

whom I owe much other valuable information bearing on the problems

raised by the Monks' Cellar).

Hyams (op. cit., 165) names Pliny the Elder as the source for his

contention "that the practice of storing and moving wine in wooden

casks was of Allobrogian origin." I am not sure that this may not be

straining the available evidence. But Hyams is surely on solid ground

when pointing out that the customs of storing and moving wine in

barrels has a prelude in the Near East, recorded by Herodotus (c. 484425

B.C.) who says that wine trade was carried on in palmwood casks

floated down the Euphrates river from Armenia on circular boats made

of skin (the source is quoted in full in Hyams, op. cit., 40).

Strabo, Geography, book V, chap. 1, ed. H. L. Jones (Loeb

Classical Library), Harvard Univ.-London, VIII, 1959, 332-33.

Strabo, op. cit., ed. cit., 316-17: κομίξουσι δ' οὗτοι μέν τὰ ἐκ θαλάττης,

καὶ οἶνον ἐπὶ ξυλίνων πίθων ἁρμαμάξαις ἀναθέντες καὶ ἒλαιον, ἐκεῐνοι δ'

ἀνδράποδα καὶ βοσκήματα καὶ δέρματα.

Egyptian & Greco-Roman methods of storing wine

The Romans, who like the Greeks and Egyptians, stored

and carried their wine in earthenware amphorae (fig. 227)

were startled by this ingenious innovation. Hyams believes

that this invention of storing wine in huge containers

formed by a multitude of separate pieces was dependent on

the more temperate climate prevalent in the lower Alps,

where barrels could more easily be kept in good condition

than in the hot and dry climate of the mediterranean

countries.[218]

Unlike the more breakable and considerably

smaller amphora used in the classical world (as an official

capacity measure the amphora was the equivalent of 25.5

liters) the wooden barrel was capable of storing wine in

larger quantities, and at considerably lower cost. Its primary

contribution to western life, however, appears to have lain

not so much in this as in the fact that it enabled man to

develop superior vintages by offering more favorable conditions

for the aging of wines. Edward Hyams purports this

fact to constitute the great difference between the wines of

antiquity (made from sweet grapes and stored in heavily

pitched containers offering poor conditions for maturing)

and the wine of modern times (made from smaller and

more acid grapes and susceptible to oxygenization under

the influence of air filtering through the pores of the

wood).[219]

From a reading of Hyam's interesting study one may

gather the impression that the ancients drank only young

wines. This is clearly not the case, as a perusal of Billiard's

exemplary and carefully documented study on wine and

vines in the ancient world will show. Pliny (Hist. Nat.,

XXIII, 22, 3) makes it a point to emphasize that a good

wine should neither be too young nor too old. Galen (De

antidotis, I, 3) and Athenaeus (Deipn., I, 26, b) write that

the wine of Alba reaches its maturity after fifteen years;

the wines of Tibur, Pompeii and Labicum after ten years.

Greek wines are said to decline after six or seven years

(Pliny, Hist. Nat., XIV, 10, 2; Athenaeus, Deipn., I, 26, b).

The wine of Falerno, bitter when young, became drinkable

after ten years, and after fifteen or twenty years acquired

the exquisite refinement that made it an incomparable

liqueur (Pliny, Hist. Nat., XXIII, 20, 2). It could attain

thirty or forty years (Petronius, Trim., XXXIV), but

having reached that age, it began to turn (Cicero, Brutus,

83).[220]

If there was a difference, then, it could not have

been in the possession or want of knowledge about the

virtues of aging but in the more favorable conditions

offered for this process by the new material used for the

containers in which wine was matured.

The ancients when faced with the problem of storing

wine in bulk, did so by putting it into large earthenware

vessels (dolia, Old Latin: calpares) which were covered by

a convex lid (operculum) sealed to the body of the vessel by

a heavy layer of pitch. These vessels were buried to the

rim in a deep layer of sand (fig. 228). Some of the larger

dolia were so high that a fully grown man could stand erect

inside without being visible. The specimen shown (fig. 227)

has a height of 6 feet 3 inches (1.90 m.), a circumference of

14 feet 8 inches (4.45 m.) and a storage capacity of 211 U.S.

gallons (800 liters). There is no need to emphasize that

these large earthenware containers must have been frightfully

expensive, since their manufacture was dependent on

firing ovens of unusual dimensions; and that to transport

them, even over small distances, posed delicate problems,

both in view of their weight and their susceptibility to

breakage. It is also quite obvious that there was a non-transgressible

upper limit for the size of an earthenware

container that had to be fired in a single piece.

Hyams, op. cit., 167. On the special role of wooden casks in aging

wine by allowing a very slow diffusion of oxygen through the wood,

and on the contribution made to the flavor of wines through the oak of

the barrel staves, see Amerine-Singleton, 1968, 107.

See Billiard, 1913, 215ff; and Seltman, 1957, 152ff. Other works

on this subject, such as Curtel, 1903; Ricci, 1924; Remark, 1927 and

Reichter, 1932 were not available to me.

The barrel: constructional & viticultural advantages

The barrel was free of any such limitations. Being composed

of a multitude of long and narrow staves (laminae,

tabulae) forced into position by iron hoops (circuli) its

volume could be extended to previously unfeasible proportions,

as witnessed by the casks, "as large as houses"

which Strabo saw in Cisalpine Gaul, or the monster cask

in the Castle of Heidelberg, which has a storage capacity

of 49,000 gallons: 232 times the volume of the large

dolium of the Maison Carrée in Nîmes (fig. 227). The

transport of such large containers posed no problem whatsoever,

since they were assembled on the spot. Smaller

barrels, as a glance at fig. 230 shows, could even be rolled

on the ground. Being set up above the ground the content

of these containers was more easily tapped than that of the

buried dolia; it did not require that the container itself be

opened, another advantage to the process of aging.

The oldest extant barrel and the earliest

visual representations

The oldest extant wooden barrel, to the best of my

knowledge, is a cask that was lifted from a pond outside the

city of Mainz in Germany, together with numerous other

Roman objects (fig. 229.B). It was filled with fillets of fish.

An oak barrel virtually contemporaneous with those

shown on the Plan of St. Gall, and of the same elongated

242. KLOOSTERBERG (near Plasmolen)

MOOK, LIMBURG, THE NETHERLANDS

[after Braat, 1934, 9, fig. 6]

This provincial Roman porticus villa is almost identical in plan with

the imperial villa of Konz (figs. 240.A, B). A third luxurious villa

of this type was excavated in Wittlich-on-the-Lieser.

trading settlement of Haithabu where, standing upright,

it formed the walls of a well (fig. 229.A). To use barrels for

that purpose appears to have been a common practice of

medieval well construction.[221]

The earliest visual representations of wine barrels are

found on the column of Trajan (A.D. 113) where Roman

soldiers are shown loading wine barrels onto a Danube

boat at a fort in Northern Yugoslavia (fig. 231), and in a

number of Gallo-Roman stone reliefs showing barrels as

they are being moved on boats or carted on wagons (fig. 232

and 233). The shape and dimension of one of these,

recorded on a Roman stone relief now in the Musé Saint-Didier

at Langres (fig. 233), appears to be identical with

that of the smaller barrels on the Plan of St. Gall. The

barrel depicted fills the entire length of a four-wheeled

wagon, and to judge by the size of the mules by which

the cart is drawn and the height of the body of its driver,

it must have had a length of roughly seven feet. It has the

same concave curvature of the staves at the two ends of

the vessel. This form may have been standard throughout

the entire first millennium A.D., for it appears again in the

Bayeux Tapestry (fig. 234) in a scene that shows William's

army setting out to conquer England, and carrying on carts

a provision of wine and weapons. The inscription leaves

no doubt about the content of this precious container:

ET HIC TRAHUNT CARRUM CUM VINO ET

ARMIS.

"And here they pull a cart with wine and with arms."

On the Roman barrel found in Mainz see Billiard, 1913, 60, fig. 69.

Some eighty other such barrels, many quite well preserved, dating from

the 1st-3rd centuries A.D., have so far been identified in various spots

along the Danube, Rhine, Thames, and the Firth of Forth. They served

as casks for transporting wine, after which they were almost invariably

re-used as well linings. For a complete listing and description of this

material with excellent bibliographical references, see Ulbert, 1959,

15-29 (Frison, 1962, dealing with the same subject, was not available

to me).

On the barrel of Haithabu and other 9th-century transport barrels

re-used as well linings, see Schietzel, 1969, 8-13 and Behre, 1969, 10-13

(a final report on Haithabu is pending).

THE MEASURE OF WINE AND BEER ALLOWED TO

THE MONKS

Conflicting views among the early fathers

Most of the early desert monks looked upon wine as an

unsuitable drink; St. Anthony never touched it and even

St. Pachomius struck it entirely from the diet of his monks

except in case of sickness.[222]

But others, such as Palladius

(d. 431) proclaimed that "it is better to drink wine with

measure than water with hubris."[223]

The moderates among

the early fathers had a powerful precedent to lean upon

since the Lord himself drank wine (Matt. IX, 11). St.

Benedict settled the controversy with his distinctive discretion.

"We do indeed read that wine is no drink for

monks; but since nowadays monks cannot be persuaded of

this, let us at least agree upon this, to drink temperately

and not to satiety."[224]

Vinum et liquamen absque loco aegrotantium nullus attingat ("Outside

the infirmary no one shall touch wine and oil"), Rule of St. Pachomius,

chap. 45, ed. Boon, 1932, 24. Even when on leave of absence from the

monastery while visiting a diseased relative, this rule was rigidly enforced;

see chap. 54 of the Rule, ed. Boon, 30.

I am taking these data from Steidle's commentary to chap. 40 of

the Rule of St. Benedict; Steidle, 1952, 238. For other early proponents

of moderate use of wine see Delatte, 1913, 315.

Licet legamus uinum omnino monachorum non esse, sed quia nostris

temporibus id monachis persuaderi non potest, saltim uel hoc consentiamus,

ut non usque ad sacietatem bibamus, sed parcius; Benedicti regula, chap. 40,

ed. Hanslik, 1960, 101-102; ed. McCann, 1952, 96-99; ed. Steidle, 1952,

237-38. The source referred to by St. Benedict is the Verba Seniorum.

Cf. Delatte, 1913, 314, note 1.

No difference in alcoholic content between ancient

and modern wines

Concerning the concentration of alcohol in wine, there

is no reason to presume any appreciable difference between

wines of ancient and modern times. Table wines (wine consumed

with meals) cannot have less than 8 per cent alcohol

by volume (at lower levels, the wine will not be stable, and

will tend to spoil), and in general no more than 12 per cent.

(At levels of alcohol higher than this, the wines are no

longer table wines but are classified as sweet wines, the

production of which requires special treatment or fortification

by artificial sugars.)[225]

The concentration of alcohol in wine is conditioned by the volume

of sugar occurring in the grapes from which the wine is made. My

colleagues, M. A. Amerine and William B. Fretter, inform me that the

sugar content of Central European grapes varies roughly between 16

per cent and an upper limit of 24 per cent, yielding a lower limit of 8 per

cent and an upper limit of 12 per cent alcohol in the wine. If the sugar

content falls below or rises above these limits, the yeast cells which

convert the sugar into alcohol will either not be capable of starting

fermentation or will cease to perform that function through attrition in

too high a volume of alcohol. For more detail on the technology of wine-making,

see Amerine and Joslyn, 1970 (2nd. ed.), especially chaps. 7, 8,

9, and 10.

The hemina of St. Benedict: Charlemagne's

attempts to establish its value

St. Benedict allows each monk "a hemina of wine a

day"[226]

and leaves it to the discretion of the prior to add

to this a little more "if the circumstances of the place, or

their work, or the heat of the summer require more."[227]

He holds out the promise of a "special reward" for those

"upon whom God bestows abstinence"[228]

and admonishes

the superior "to take care that neither surfeit nor drunkeness

supervene."[229]

The precise content of the measure of

wine which St. Benedict designated with the term hemina

is unknown.[230]

Charlemagne made an attempt to ascertain

243. GERASA (JERASH), PALESTINE. THREE EARLY CHRISTIAN SANCTUARIES ON AXIS

[after Krautheimer, 1965, 119, fig. 50]

In the foreground and to the left the atrium and church of St. Theodore, built A.D. 494-496; in the center, but on a slightly lower level, the

cathedral of Gerasa, built around A.D. 400. It had at its rear another atrium enclosing a shrine of St. Mary located directly behind the apse of

the cathedral. This atrium was approached by a grand staircase from yet a lower level. Three sanctuaries were thus aligned on a common axis.

244. CANTERBURY, ENGLAND

PLAN OF SAXON ABBEY CHURCH OF SS PETER AND PAUL, FOUNDED BY ST. AUGUSTINE (597-604), AND THE CHURCH OF ST. MARY

[same period; after Clapham, 1955]

To the left lies the church of SS Peter and Paul; to the right, the church of St. Mary. The church of St. Pancras, lying in eastern

prolongation of the axis of these two churches, and dating from the same period, is not visible in this plan. The church of St. Wulfric (interposed

between SS Peter and Paul and St. Mary) was not part of the original concept. In the medieval monastery of St. Gall, St. Peter's chapel

(prior to 830), Gozbert's church (830-836) and Otmar's church (dedicated 867) lay in axial prolongation; see II, figs. 507-509.

Hildemar, in discussing this event, in his commentary to

chapter 40 of the Rule of St. Benedict, claims that the

emperor succeeded in retrieving the old measure and that

this was the measure currently used in the monasteries of

the empire as the basis for the daily allotment of wine.[231]

The event is also referred to in a letter by Abbot Theodomar

of Monte Cassino to Charlemagne, where it is said

that a sample measure was dispatched to the emperor. Two

of these according to the estimate of the older brothers of

Monte Cassino formed the equivalent of the hemina of St.

Benedict, one being served at the midday meal, the other

at supper.[232] The text leaves no margin for doubt: it was

not the original hemina of St. Benedict (or a duplicate

thereof) that the emperor received from Monte Cassino

but a sample of which the senior monks "supposed"

(aestimaverunt, i.e., judged by careful consideration, yet

from incomplete data) that it was half the equivalent of that

measure. St. Benedict's original hemina, as we learn from

Paul the Deacon's History of the Lombards had been taken

to Rome by the Monks of Monte Cassino, as they fled from

the invading barbarians in 581, together with the original

measure for the Benedictine pound of bread, and the

original manuscript of the Rule of St. Benedict.[233] There

is no evidence that these two measures were returned to

the monastery in 720 when it was rebuilt, and the content

of Theodomar's letter, as well as a good deal of other

evidence, indicates clearly that in the eighth century even

in St. Benedict's own monastery the precise value of the

Benedictine hemina was forgotten.[234]

Tamen infirmorum contuentes inuecillitatem credimus eminam uini per

singulos sufficere per diem. Benedicti regula, loc. cit.

Quod si aut loci necessitas uel labor aut ardor aestatis amplius poposcerit,

in arbitrio prioris consistat. Benedicti regula, loc. cit. The reform

synod of 816 confirmed the directive of St. Benedict that a special

measure may be added to the regular pittance of wine on days on which

the monks were subject to heavy labor, and added to those the days

when they celebrated the mass for the dead. Synodi primae decr. auth.,

chap. 11; ed. Semmler, Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963, 163, 373.

Quibus autem donat deus tolerantiam abstinentiae, propriam se

habituros mercedem sciant. Benedicti regula, loc. cit.

Endless discussions have been carried on with regard to this subject,

ever since Claude Lancelot, in 1667 published his Dissertation sur

l'hemine et la livre de pain de Saint Benoit et d'autres anciens religieux.

(For this and other early literature on the subject see Delatte, 1913, 309

and 313ff.) The issue may never be solved to full satisfaction, but it has

fascinating cultural implications; and the question just how seriously

the design, the dimensions and the number of the barrels in the Monks'

Cellar must be taken, cannot be settled without establishing, at least in a

tentative form the upper and lower limits of the daily ration of wine that

each monk was permitted to drink with his meal at the time of Louis the

Pious, the reason we attach some importance to this subject.

Unde Carolus rex, qualiter ipsam heminam intellegere ac scire potuisset,

misit Beneventum ad ipsam monasterium S. Benedicti, et ibi reperit antiquam

heminam, et juxta illam heminam datur monachis vinum. Similiter

et juxtam eam habemus etiam et nos. Expositio Hildemari, ed. Mittermüller,

1880, 445.

Misimus etiam mensuram potus, quae prandio, et aliam, quae cenae

tempore debeat fratribus praeberi; quas duas mensuras aestimauerunt

maiores nostri emine mensuram esse. Direximus etiam et mensuram unius

calicis, quam obsequiaturi fratres iuxta sacrae regulae textum solent accipere.

Theodomari epistola ad Karolum regem, chap. 4; ed. Hallinger and

Wegener, Corp. cons. mon., I, 1963, 163. There is some question about

the authenticity of this letter. See Hallinger and Wegener, loc. cit.;

Semmler, 1963, 53-54; and Winandy, 1938.

Pauli Historia Langobardorum, Book IV, chap. 17; ed. Bethman

and Waitz, Mon. germ. hist., Sript. rer. Lang., Hannover 1878, 122:

Circa haec tempora coenobium beati Benedicti patris, quod in castro Casino

situm est, a Langobardis noctu invaditur. Qui universa diripientes, nec unum

de monachis tenere potuerunt, ut prophetia venerabilis Benedicti patris . . .

dixit . . . Fugientes quoque ex eodem loco monachi Roman petierunt secum

codicem sanctae regulae, quam praefatus pater composuerat, et quaedam

alia scripta necnon pondus panis et mensuram vini et quidquid ex supellecti

subripere poterant deferentes.

The Carolingian inflation of capacity measures

The leaders of the Church, under Charlemagne, and

even more so under Louis the Pious, had some reason to

be concerned with this issue, since in the lifetime of these

two rulers, the hemina had more than doubled its value.

The base of the Carolingian system of capacity measure,

as that of the Romans, was the modius internally divided

into 2 situlae, 16 sextarii, and 32 heminae. The classical

Roman modius had a capacity equivalent to 8.49 liters, the

hemina to 0.2736 liters.[235]

Between the fall of the Roman

Empire and its renovation under Charlemagne the capacity

use in the Frankish kingdom and in the early years of the

reign of Charlemagne was equivalent to 34.8 liters. In a

capitulary of 794, Charlemagne instituted a new modius,

larger by one third than the preceding one, which brought

the modius up to an equivalent of 52.2 liters. Before 822,

Louis the Pious increased again the newly established

modius of his father, this time by one fourth of its current

value, which brought it up to an equivalent of 68 liters.

Thus in the short span of not more than 25 years, the

hemina had risen from a capacity equivalent to 1.06 liters

(in use when Charlemagne acceded to his throne) to one

equivalent to 1.46 liters (instituted by Charlemagne in 794)

and finally to one equivalent to 2.12 liters (instituted by

Louis the Pious, prior to 822).[236] The inflation clearly

worked in favor of the monks, with proportions that must

have taxed the wit of even the most astute monastic leaders.

St. Benedict may have foreseen such possibilities when he

foreclosed all future abuse with the qualifying clause that

whatever measure of wine the abbot should be willing to

grant, "he always take care that neither surfeit nor drunkeness

supervene,"[237] a directive that as the centuries passed

by must have proved to be a more trustworthy guide than

any reliance on capriciously changing physical capacity

measures.

For the liter equivalents of the old Roman modius and hemina see

Pauly-Wissowa, Real Encyclopädie, s.v.

I am basing these calculations on the data assembled by M. G.

Guérard, who deals with Carolingian measures of capacity, on pp. 183ff

and 960ff of his admirable work on the Polyptique of Abbot Irminon

(Guérard, I, 1844. If Guérard's analysis of the relative values of the

measures here cited is wrong, my conclusions will be wrong. I have no

reason to doubt his findings.

The probable daily allowance of wine at the time

The Plan of St. Gall was drawn

The hemina that St. Benedict had in mind probably

came closer to that which was in use under the Romans in

classical times than to any of the later Frankish measures.

This would have entitled the monks to drink a little over a

fourth and perhaps as much as a third of a liter of wine

per day. Whether taken in the course of a single meal or

spaced out over two meals, this amount could hardly have

had any damaging effects on health or have lead to "surfeit"

or "drunkeness," especially not if these meals were

followed, as they traditionally were, by either a brief

period of rest,[238]

or by sleep.[239]

St. Benedict's assessment

of the quantity of wine that could be safely consumed at

the monks' table was both conservative and judicious. But

in evaluating his ruling historically one must not lose

sight of the fact that when St. Benedict took the epochal

step of sanctioning the consumption of wine for the

monastic community, the issue was as yet a highly controversial

one. Once the decision was made, the frailties of

human nature would tend to push the allowance upward.

From 0.2736 liters to 0.5 liters is not a big step; the less so,

if one considers the great inflation the hemina experienced

as an official capacity measure between the time of St.

Benedict and the time of Louis the Pious. That the daily

monastic allowance would follow this inflationary cycle,

which peaked under Louis the Pious to the impressive

equivalent of 2.12 liters, is impossible to assume. That it

rose to 0.5 liters is probable. There are even some indications

that it might have risen as high as 0.7 liters. A half-liter

of wine per day, if consumed by a healthy man in the

course of two successive meals, could still be interpreted as

lying within the spirit of St. Benedict's ruling; 0.7 liters

would have pushed the Rule to its limit; any amount above

that would have been clearly in violation of the Rule.[240]

My suspicion that the daily allowance of wine might have

risen as high as 0.7 liters at the time of Louis the Pious is

based upon a well known but perhaps not fully explored

passage in the Customs of Corbie, where we are told that in

this monastery each visiting pauper was issued two

245. BOOK OF KELLS. DUBLIN, TRINITY COLLEGE LIBRARY. MS 59, fol. 188r

OPENING WORDS OF ST. MARK GOSPELS

[by courtesy of the Trustees of Trinity College]

246. PLAN OF ST. GALL

DIAGRAM SHOWING THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE PRINCIPAL BUILDING MASSES

The shape of Church and Claustrum bears striking resemblance to the Quoniam initial of the St. Mark Gospels, Book of Kells (fig. 245).

The building masses grouped around this central motif likewise recall the manner in which secondary letter blocks are ranged peripherally

around the initial. The similarity may be accidental, if not deceptive, since the prime reasons for grouping buildings on the Plan of St. Gall (as

well as the development of the claustral scheme) are clearly funtional. Yet one cannot entirely discard the possibility of an interplay of

functional with aesthetic considerations.

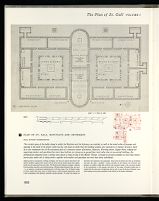

247. PLAN OF ST. GALL. NOVITIATE AND INFIRMARY

PLAN. AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

The circular apses of the double chapel to which the Novitiate and the Infirmary are attached, as well as the round arches of passages and

openings in the walls of the cloister walks (see fig. 236) leave no doubt that this building complex was conceived as a masonry structure. Each

of its two components has all the constituent parts of a monastic cloister (Dormitory, Refectory, Warming Room, Supply Room, lodgings for

supervising teachers and guardians) but since these facilities are strung out on ground floor level rather than in two-storied buildings, this

architectural compound covers a surface area almost as large as that of the Monks' Cloister. It housed in practice probably no more than twelve

novices plus twelve sick or dying monks—together with teachers and guardians not more than thirty individuals.

Differing dietary prerogatives, bathing privileges, and need for special educational and

medical facilities, required that novices and the ill not only be housed apart from regular

monks, but also separated from each other. The Novitiate and Infirmary complex—inspired

by the grandiose centrality and axial bisymmetry of Roman imperial palaces (figs. 240-242)

—is an ingenious architectural implementation of all these needs. Two U-shaped ranges

of rooms around open inner courts, on either side of a church halved transversely, served

a dual constituency with identical, mutually isolated facilities. No doubt the location of

Novitiate and Infirmary was purposeful. Away from the bustle and noise of workshops

and near the open, "parklike" eastern paradise of the Church, the Orchard, and

gardens, its residents might find activities and recreation suited to the returning strength

of the convalescent, or the energies and spirits of the young. Proximity might serve to

remind both ill and novices of beginnings and an end, in view of the great Cemetery cross,

while healing and learning continued in the embrace of the larger community.

passage discloses that the "beaker" of Corbie was capable

of holding 1/96 of a modius[241] which in the light of the

values established by M. B. Guérard for capacity measures

in use at the time when this text was written (A.D. 822)

would amount to 0.7 liters.[242] The passage does not refer

to wine but to beer; however, the relative value of wine

and beer had been defined in 816 in the first synod of

Aachen, in a chapter which directed that if a shortage of

wine were to occur in a monastery, the traditional measure

of wine should be replaced by twice that volume of beer:

ubi autem uinum non est unde hemina detur duplicem eminae

mensuram de ceruisa bona . . . accipiant.[243] This directive was

promulgated as an imperial law and must have been known

to everyone in the empire.

Truly enough the Customs of Corbie speak of rations to

be issued to the poor, not to the monks, but since from

another chapter of that same text it can be inferred that

monks and paupers are entitled to the same ration of

bread,[244]

there is more than a high probability that they

were also granted the same ration of wine or beer. Good

monastic custom would require that an equal amount be

also granted to the serfs. The latter might even have been

issued slightly larger rations because of their involvement

in hard physical labor.

After the evening meal, which was succeeded only by a brief period

of reading and by Compline. See Benedicti regula, chap. 42; ed. Hanslik

1960, 104; ed. McCann, 1952, 100-101; ed. Steidle, 1952, 240-41.

The effect of wine or beer on man depends on the concentration of

alcohol in the blood, and this in turn is dependent on the manner in

which the intake is spaced out over the day and to what extent the

alcohol is diluted by food. Dr. Alfred Childs, an expert on alcohol in the

School of Public Health of the University of California at Berkeley,

advises me that half a liter of wine, spaced out over two meals, and

allowing for some rest after the midday meal, would not have any

damaging effects although it might well involve some temporary impairment

of cerebration during earlier phases of the period during which the

alcohol is metabolized. Even 0.7 liters, if spaced out over two meals and

diluted by food, Dr. Childs opines, might still be within the safety limits

set by St. Benedict (i.e., neither lead to "surfeit" nor "drunkeness")

but would be pushing it close to the edge of these limits. For an analysis

of the metabolism of alcohol, the mechanism of its toxic effects and its

rational use by healthy persons, see Childs, 1970.

Consuetudines Corbeienses, chap. 4; ed. Semmler, Corp. con. mon., I

1963, 373; and Jones, III, Appendix II, 105; where it is stipulated that a

quarter of a modius or four sesters of beer be divided daily among twelve

paupers, "so that each will receive two beakers." From this it must be

inferred that there were 96 beakers in a modius (I do not see how Semmler

arrived at the figure of seventy-two. Semmler, 1963, 54). Since in 822

when the Customs of Corbie was written, the official capacity of the

modius was 68 liters, the beaker of Corbie must have been the equivalent

of 0.7 liters. The directive reads as follows: De potu autem detur cotidie

modius dimidius, id sunt sextarii octo, de quibus diuiduntur sextarii quattuor

inter illos duodecim suprasriptos, ita ut unusquisque accipiat calices duos.

Synodi primae decr. auth., chap. 20; ed. Semmler, Corp. cons. mon.,

I, 1963, 463. Chrodegang ordered replacement of wine by an equal

amount of beer (chap. 23, Regula canonicorum, ed. J. B. Pelt, Etudes sur

la Cathedrale de Metz IV, La Liturgie, 1, Metz, 1937, 20).

On the number of loaves of bread and their distribution in the

monastery see Consuetudines Corbeienses, chap. 3; ed. Semmler, Corp.

cons. mon., I, 1963, 375ff; and Jones, III, Appendix II, 106.

ARE THE BARRELS DRAWN TO SCALE AND

SCALED TO NEED?

The layout of the Monks' Cellar raises some interesting

dimensional questions. Are the scale, the size, and the

number of its barrels to be taken seriously? Or are they

meant to simply indicate in a schematic and purely general

way that there is a cellar full of barrels for the storage of

wine and beer?

An answer to this question depends on our ability to

assess the total number of men who were to be housed in a

monastery such as that which is shown on the Plan of St.

Gall, the extent of their total annual need for storage of

alcoholic beverages, and the relation of this need to the

storage capacity of the barrels that are drawn out on the

Plan.

In entering upon a discussion of these relationships,

one has to keep in mind, first, that the wine for an entire

year is manufactured in the fall and must be stored in its

entirety at that time; second, that this wine cannot be

tapped during the first six months of storage (during which

it is still in full process of fermentation) and preferably

should not be tapped during the first twelve months. This

means that a well planned monastic cellar should be able to

hold the entire yield of not less than two years' vintage.

Beer, unlike wine, was not a seasonal product, but could be

manufactured all year round.[245]

It needed only a few weeks

of recovery in the cellar for clearing and therefore no large

facilities for long range storage.

A calculation of the probable number of people daily to

be fed in the monastery shown on the Plan of St. Gall

discloses that it consisted of about 110 monks, some 150170

serfs, plus an indeterminate and varying number of

guests: all together roughly 300.[246]

Our analysis of the

layout of the Monks' Cellar has shown that there are nine

small barrels, each of a length of ten feet and a central

diameter of five feet; and five large barrels each of a length

of fifteen feet and a central diameter of ten feet.[247]

My friend

and colleague William B. Fretter (experienced vintner,

and mathematician), by a calculation based on the apparent

dimensions of the barrels portrayed on the facsimile

Plan, concluded that each small barrel contained 4,250

liters and each large one, 28,250 liters. These capacities

vary slightly from those determined by Ernest Born (Fig.

235.A-C, p. 286). Both tend to confirm nonetheless that

the scale of the barrels on the drawing is not capricious,

but an intentional representation of casks the size of which

related directly to the needs of the inhabitants of the proposed

community.

On the preceding pages it has been shown that the daily

allowance of wine for each monk at the time of Louis the

Pious could not have been less than 0.2736 liters (old

Roman hemina) and is very unlikely to have been more than

0.7 liters. The most persuasive historical assumption is

probably that it was somewhere in the middle between

these two extremes, perhaps around 0.5 liters. This gives

us a lower and upper limit as well as an intermediate value,

all of which can be checked against the storage capacity of

the barrels actually shown on the Plan.

1. If the daily allowance was 0.2736 liters (fig. 235.B):

If the normal daily allowance of wine had still been the

old Roman hemina of 0.2736 liters the total daily consumption

of wine for 300 people would have been 82 liters,

the total yearly consumption, 29,930 liters. To store two

years of vintage in this order of magnitude would have

required barrel space for 59,860 liters. This amount could

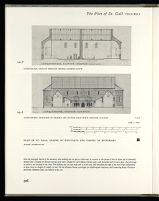

PLAN OF ST. GALL. NOVITIATE AND INFIRMARY. ELEVATION AND SECTION

248.A CROSS SECTION THROUGH CLOISTER AND CHAPEL LOOKING WEST

248.B WEST ELEVATION

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

The absence of explanatory titles to indicate the existence of any upper stories, as well as the fact that the ground floor accommodates all

parts of the traditional claustral scheme, is clear evidence that all rooms of the Novitiate and Infirmary lay at ground level. In reconstructing

the elevations and sections of this compound shown in this and the subsequent figure, we have followed the procedure chosen for every other

building on the Plan by conjecturing comfortable minimum heights for each part of the complex: head clearance in the cloister walks, sufficient

elevation in the walls of the chapels to receive the roof covering them, and sufficient height in the clerestory above that level to allow for

proper fenestration. The outer wall perimeter, likewise, must have been of sufficient height to allow for windows giving light and air to the

rooms they enclose.

Cellar, but would have left a number of barrels empty, or

for the storage of beer, which seems excessive: three of the

large ones, and all of the nine small ones. We have already

pointed out that from a purely historical point of view it

seems unlikely that the daily measure of wine at the time

of Louis the Pious was still the old Roman hemina of

0.2736 liters. Our analysis of the storage capacity of the

Monks' Cellar would tend to confirm this assumption.

The Cellar, if it was rationally planned, must have been

planned for a larger volume of alcoholic beverages.

2. If the daily allowance was 0.5 liters (fig. 235.C):

If the normal daily allowance of wine was 0.5 liters; the

daily consumption for 300 people would have been 150

liters, the needed supply for one year, 54,750 liters; for

two years, 109,500 liters. This amount could have been

stored in four of the five larger barrels, leaving the fifth for

the storage of beer, and all the smaller barrels for the aging

of smaller quantities of higher quality wine, perhaps

reserved for distinguished guests and for the abbot when

he dined with distinguished guests.

It is interesting to note that under this assumption,

which we found to be historically the most persuasive one,

the physical layout of the Monks' Cellar makes perfect

sense. It offers comfortable space for everything, leaving

perhaps even a small margin for extra needs—a condition

that we found to prevail everywhere else in analyzing the

scale of the Plan.[248]

3. If the daily allowance was 0.7 liters:

If the normal daily allowance was 0.1 liters, the daily

consumption for 300 people would have been 210 liters;

the needed supply for one year 76,650 liters; for two years,

153,300 liters. 153,300 liters would have occupied all of the

five large barrels, plus three of the smaller ones, leaving

only six of the smaller barrels for other purposes, such as

the long term storage of wines of higher quality for aging,

or the short term storage of beer.

Again it is interesting to note that under this assumption,

which lies at the borderline of what would have been

acceptable within the tenets of the Rule of St. Benedict,

would also in the physical sense have been a very tight fit.

For a detailed substantiation of these figures see our chapter "The

Number of Monks and Laymen," below, pp. 342ff.

See our chapters "Scale and Construction Methods used in

Designing the Plan," above, pp. 77ff and "Schematic Drawing or

Building Plan? The Problems of Scale and Function," above, pp. 112ff.

CONCLUSION

All of these calculations tend to show that the storage

capacity of the barrels in the Monks' Cellar was carefully

planned, and that the person who decided on the number

and the dimensions of the barrels shown in the cellar, as

well as the dimensions of the cellar itself, had a clear and

accurate statistical picture of the total annual needs in

alcoholic beverages of the community for which the cellar

was designed, as well as the precise volume of cooperage

required to meet these needs. In the light of the results of

our general analysis of the scale and construction methods

used in designing the Plan, these findings will not come as

a surprise.

LACK OF FACILITIES FOR THE PRESSING

OF GRAPES

The Plan of St. Gall does not provide facilities for the

pressing and processing of grapes. This work was probably

performed in the outlying vineyards. The climatic and

topographical conditions of many monasteries were such

that the cultivation of grapes in their immediate vicinity

was impossible. We know, for instance, that in the eighth

and early ninth centuries, the Abbey of St. Gall had to

import its wine from vineyards in Breisgau, and from

others located in the Alsace.[249]

Later the grape was introduced

into the neighboring Thurgau. In the days of Abbot

Notker (971-975) and his skillful prior Richer, there were

years when the supply was so abundant, the cellar could

not hold it, and the overflow had to be stored in the

open under guard. Spoiled by so much good fortune,

the monks became fastidious enough to reject the red wine

in favor of the white although, as Ekkehart remarks, "it

had been a good vintage."[250]

Wine and beer were probably not the only fermented

drinks available to the monks. Ekkehard, in his Benedictiones

ad mensas, refers to cider, spiced wine (Sabenwein,

savina), mulberry wine, heated wine, mead and wine mixed

with honey.[251]

Bikel, 1914, 106. Ekkeharti (IV.) Casus sancti Galli, chap. 134;

ed. Meyer von Knonau, 1877, 426-29; Helbling, 1958, 222-24.

Benedictiones ad mensas, verses 222-80. See Liber benedictionum

Ekkehart's IV; ed. Egli, 1909. Dr. Johannes Duft brings to my attention

that Ernst Schulz, 1941, 199-234, has demonstrated that Ekkehart's IV.

Benedictiones ad mensas were modelled after the Etymologiae of Isidore

of Seville and for that reason should not be taken as a realistic reflection

of the monks' diet, as Egli, in his 1901 edition understood it to be.

Larder

The Monks' Cellar and Larder is the only one of the three

principal claustral structures to communicate directly with

the service yard to the south of the Claustrum. A door in

the middle of its southern gable wall opens into the court

around the Kitchen and other adjacent yards. This connection

is indispensable, since in addition to wine and

beer, all the meats and staples stored in the Larder above

the Cellar had to be brought in from the outer areas.

As with the Dormitory and the Refectory, the plan of the

Cellar tells us nothing about the location of the stairs that

connected the ground floor with the upper level, and since

the Plan concentrates on the furnishings of the Cellar, we

are left in the dark about the layout of the Larder. This gap

can fortunately be closed by a vivid literary account from

the pen of Abbot Adalhard. In a chapter devoted to a discussion

of the "number and disposition of the pigs,"[252]

PLAN OF ST. GALL. CHAPEL OF NOVITIATE AND CHAPEL OF INFIRMARY

249.B LONGITUDINAL SECTION THROUGH CHAPELS LOOKING SOUTH

249.A LONGITUDINAL ELEVATION OF CHAPELS AND SECTION (EAST-WEST) THROUGH CLOISTER

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

Like the principal church of the monastery this building has an apse at either end; in contrast to the former it has no aisles and is internally

divided into a Chapel for Novices (facing east) and a Chapel for Sick Monks (facing west), each furnished with its own altar, the patronage

of which is not disclosed in its titles. The building was 27½ feet wide and 110 feet long, and including the ridge of its roof is here conjectured

to have risen to a height of roughly 50 feet. On the ultimate Roman prototypes for double-apsed structures, and connecting Early Christian

and Early Medieval links, see caption to fig. 111.

killed per year "at the cellar" of Corbie amounted to 600.

Sixty of these went to the porter for the table of the guests,

370 to the cellarer for the sustenance of the serfs and the

sick monks, 120 to the prebendaries and fifty into the

abbot's reserve.

The 370 pigs that went to the cellarer for use by the

serfs and the sick were to be issued at the rate of one pig

per day (365 a year), leaving a reserve of five to be used for

emergencies. These 370 pigs, the abbot tells us, are to be

hung in the larder, entrails and all, in monthly batches of

thirty. If anything is left over from the previous month, it

must remain hanging in its place and may be removed only

if a shortage occurs in the meat or fat supply of the subsequent

month. Never should the cellarer "take anything

from a future month to compensate for a shortage of a

preceding month," but always "a shortage of the following

month must be covered by a saving from the preceding

month." Since the entrails spoil faster than the meat and

the lard, they must be distributed first. And since the lard,

when rendered in January, is not fit for consumption before

Easter, the cellarer must build up a reserve from the preceding

year, to be used during this critical interval.[253]

One cannot infer from Adalhard's account that a full

year's supply of pork was hung at the first of January.

Several months' batches must have existed at a given time,

however, since otherwise the abbot could not have warned

against the loan of meat from a following month to make

up for a shortage incurred in the preceding month. One

must remember that in the Middle Ages, when farming

practices provided only a limited supply of winter food for

stock, at the end of each year the farmers customarily killed

all but a small number of their cattle, sheep, and pigs and

salted down the flesh for their winter meat supply. The

traditional month for slaughtering pigs was December. In

the illuminations of medieval calendars illustrating the

labors of the months, this event is depicted with lavish

attention.

Adalhard tells us nothing about the disposition in the

larder of the other kinds of meat, but if we add to the pig

the carcasses of beef, mutton, and goat, and the vast array

of sacks or baskets filled with beans, lentils, and onions,

plus the racks of fruit, cheeses, and bread that passed

through the larder, we have a fairly vivid picture of the

disposition of the 2,700 square feet of storage space above

the Cellar that insured the livelihood of the community.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||