The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| I. 1. |

| I.1.1. |

| I.1.2. |

| I.1.3. |

| I.1.4. |

| I.1.5. |

| I.1.6. |

| I.1.7. |

| I. 2. |

| I.2.1. |

| I. 3. |

| I.3.1. |

| I.3.2. |

| I.3.3. |

| I. 4. |

| I.4.1. |

| I.4.2. |

| I. 5. |

| I.5.1. |

| I.5.2. |

| I.5.3. |

| I. 6. |

| I.6.1. |

| I. 7. |

| I.7.1. |

| I.7.2. |

| I.7.3. |

| I.7.4. |

| I. 8. |

| I. 9. |

| I.9.1. |

| I. 10. |

| I.10.1. |

| I.10.2. |

| I. 11. |

| I.11.1. |

| I.11.2. |

| I. 12. |

| I.12.1. |

| I.12.2. |

| I.12.3. |

| I.12.4. |

| I.12.5. |

| I.12.6. |

| I.12.7. |

| I. 13. |

| I.13.1. |

| I.13.2. |

| I.13.3. |

| I.13.4. |

| I.13.5. |

| I.13.6. |

| I.13.7. |

| I.13.8. |

| I. 14. |

| I.14.1. |

| I.14.2. |

ANACHRONISM IN MENSURATION |

| I.14.3. |

| I.14.4. |

| I.14.5. |

| I.14.6. |

| I.14.7. |

| I.14.8. |

| I.14.9. |

| I. 15. |

| I.15.1. |

| I. 16. |

| I. 17. |

| II. |

| II. 1. |

| II.1.1. |

| II.1.2. |

| II.1.3. |

| II.1.4. |

| II.1.5. |

| II.1.6. |

| II.1.7. |

| II.1.8. |

| II.1.9. |

| II.1.10. |

| II.1.11. |

| II.1.12. |

| II.1.13. |

| II. 2. |

| II.2.1. |

| II.2.2. |

| II. 3. |

| II.3.1. |

| II.3.2. |

| II.3.3. |

| II.3.4. |

| II.3.5. |

| II.3.6. |

| II.3.7. |

| II.3.8. |

| II.3.9. |

| II.3.10. |

| III. |

| III. 1. |

| III.1.1. |

| III.1.2. |

| III.1.3. |

| III.1.4. |

| III.1.5. |

| III.1.6. |

| III.1.7. |

| III.1.8. |

| III.1.9. |

| III.1.30. |

| III.1.11. |

| III. 2. |

| III.2.1. |

| III.2.2. |

| III.2.3. |

| III.2.4. |

| III.2.5. |

| III.2.6. |

| III.2.7. |

| III.2.8. |

| III. 3. |

| III.3.1. |

| III.3.2. |

| III.3.3. |

| III.3.4. |

| III.3.5. |

| IV. |

| IV. 1. |

| IV.1.1. |

| IV.1.2. |

| IV.1.3. |

| IV.1.4. |

| IV.1.5. |

| IV.1.6. |

| IV.1.7. |

| IV.1.8. |

| IV.1.9. |

| IV.1.10. |

| IV.1.11. |

| IV.1.12. |

| IV. 2. |

| IV.2.1. |

| IV.2.2. |

| IV.2.3. |

| IV. 3. |

| IV.3.1. |

| IV. 4. |

| IV.4.1. |

| IV.4.2. |

| IV. 5. |

| IV.5.1. |

| IV. 6. |

| IV.6.1. |

| IV. 7. |

| IV.7.1. |

| IV.7.2. |

| IV.7.3. |

| IV.7.4. |

| IV.7.5. |

| IV.7.6. |

| IV.7.7. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

ANACHRONISM IN MENSURATION

Reinle believes he has discovered that the Plan of St. Gall

was drawn at a scale of 1:200.[345]

He is not the first to

advance this view. Wilhelm Rave had expressed himself

along similar lines in 1956,[346]

and Emil Reisser likewise, in a

study published posthumously in 1960.[347]

The Plan is, indeed, drawn to a scale that comes close to

what we would define today as a ratio of 1:200. But it is one

thing to observe that the Plan was drawn at a scale that

corresponds or comes close to the ratio of 1:200; it is quite

another to claim that it was actually drawn at that scale. In

proposing this view, Reinle is caught in an anachronism.

The concept 1:200 is not a medieval concept and does not

make sense within the medieval system of mensuration. If a

modern architectural drawing is said to be laid out at a

scale of 1:200, this means that one unit on the drawing

corresponds to 200 identical units on the ground. The base

of this ratio is decimal. A medieval architect could not have

expressed himself in these terms, since the two basic units

of measurement with which he worked, the foot and the

inch, were internally divided not into tenths, but into

twelfths and sixteenths (a system that still persists in

England and the larger Anglo-Saxon world) or into

twelfths and twelfths (the pied royal de France, which was

used in France until the introduction of the metric system).[348]

The foot and its primary subdivision, the inch, were

derived from the human body.[349]

Twelve thumb-breadths

of a fully grown man equal the length of his foot (fig. 57).

This is the raison d'être for the twelve units of the English

foot. The French word pouce, the Old French poulcée, the

Latin pollex—all meaning "thumb"—reflect the history of

the genesis of this measure. Like the English foot, the

Latin foot consisted of twelve units[350]

"Inch," Anglo-Saxon

ynce, comes from Latin uncia = "a twelfth"; and

the duodecimal graduation of the Roman foot is reflected

in the series: uncia = 1/12;

| sextans | = 2/12 or ⅙ |

| quadrans | = 3/12 or ¼ |

| triens | = 4/12 or ⅓ |

| quincunx | = 5/12 |

| semipes | = 6/12 or ½ |

| septunx | = 7/12 |

| bes | = 8/12 or ⅔ |

| dodrans | = 9/12 or ¾ |

| dextans | = 10/12 or ⅙ |

| deunx | = 11/12 |

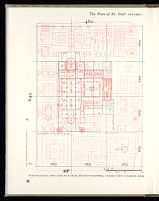

62. PLAN OF ST GALL: SHOWING 40 FOOT MODULE SUPERIMPOSED UPON

THE ENTIRE SITE OF THE MONASTERY

The human body does not offer reliable guidance for

divisions smaller than the breadth of a thumb. These

smaller units could only be obtained by instrumental

operations, and the simplest, easiest, and for that reason,

probably the oldest, way of graduating a distance into a

sequence of consistently decreasing smaller units is the

method of continuous halving—a procedure by means of

which a whole is reduced to a half, a half to a quarter, a

quarter to an eighth, and eighth to a sixteenth (fig. 58).[351]

This is the procedure that created the sixteen graduations

of the English inch.[352]

We know nothing about the internal divisions of the

Carolingian inch, but whether it was graduated into twelfths

or into sixteenths, this much is certain: there was no

common decimal denominator between a Carolingian inch

and a Carolingian foot that could be expressed in the ratio

1:200.

The modern metric scale is based on a comparison of

parts of like nature, all of which can be understood either

as fractions or as multiples of ten. The medieval scale has

no such common unit of reference. It is a combination of a

variety of different forms of graduation (sedecimal, duo-

1. Corporibus. Scilicet non solum de temporibus.

2. Miliarium. Id sunt mille passus. Legua enim ·I· D· passus.

3. Stadium. Id est ·CXXV· passus. Stadium octava pars miliarii est.

4. Iugerum. ·XLVIII· passus. Iugerum est quod possunt duo boves in una

die arare, id est iornalis.5. Perticam. Decem pedes . . .

6. Dimidium. Id est medietas.

7. Semis. Scilicet non solum appellatur medietas librae semis, sed etiam

medietas cubiti et ideo dixit in corporibus.8. Semis. Scilicet ubi semis ponitur, non ponitur et coniunctio.

9. Semissem. Id est dimidium. Accusativus a semis.

"Bede had asserted that the traditional measures had to be adapted to

duodecimals. But the Metz glossator, in introducing these definitions,

gratuitously introduced other schemes of fractions. Granted (2) that a

mile is a thousand paces, a league is 3/2 thousand. A stade (3) is 125

paces, an eighth of a mile. An acre (4) is 48 paces, a rod (5) ten paces. At

this stage of the pattern, medietas (6), the mid-point, becomes a congenial

concept for one half, not only for the semi-pound (7) but for the semicubit,

`and therefore it is used in measuring bodies,' a usage justified

for Bede by no lesser an authority than Moses (Exodus xxv.10) who used

dimidium and semissem in the same sentence interchangably. Hence it

seems that the Metz glossator found it easy, with his mind centered on

the building measurements of Noah's and Moses' arks, to introduce a

scheme of fractions quite at odds with the duodecimalism he was teaching

as the determining ratio of weights and measures."

63. PLAN OF ST. GALL: ONE LINE OF A GRID, 160 FOOT MODULE, FIXED THE CHURCH AXIS

be expressed in the terms of a decimal sequence.

It would be correct to say that the Plan of St. Gall is

drawn to a scale in which one sixteenth of a Carolingian

inch on the drawing corresponds to one Carolingian foot

on the ground. To convert this scale into a relationship in

which the ratio is expressed in the form of like units

requires that the base value of one sixteenth of an inch be

multiplied first by 16 (the sixteen parts of the inch) and then

by 12 (the twelve parts of the foot): 16 × 12 = 192,[353]

the

number of sixteenths of an inch in a foot. The ratio 1:192

is not far from the ratio 1:200, but it is not identical with it

and should, under no circumstances, be confused with it.[354]

In medieval mensuration the scale relationship 1:200 not

only did not exist, it would have been meaningless.[355]

This

fact by itself precludes that the axial title of the Church

could have meant what Reinle purports it to mean, and

thus we are taken back to Boeckelmann's interpretation as

the most reasonable explanation of the dimensional incongruities

of the Plan.

Rave, 1956, 47: "Die Planung des Baumeisters ist geradeso wie

noch meistens unsere heutigen Vorentwürfe im Masstab 1:200 aufgetragen."

For general information see the articles "Weights and Measures"

in Encyclopedia Britannica, and "Poids et Mesures" in Grande Encyclopédie,

XXVI, Paris, n.d., 1184-96, as well as the literature there cited.

Vitruvius, De Architectura, Book 3, chap. 1.5 expresses himself on

this issue as follows: "Mensurarum rationes . . . ex corporis membris

collegerunt, uti digitum, palmum, pedem, cubitum" (see Vitruvius, On

Architecture, ed. Granger, I, 1931, 160ff).

With regard to the Roman foot, see Jacono, 1935, 167-68; for a

fuller account see Hultsch, 1862, 59ff; 1882, 74ff. Of great importance

for the medieval history of the inch is Bede's chapter "De ratione

unciarum" in his De temporum ratione, chap. 4, which Charles W.

Jones brought to my attention. See Bedae opera de temporibus, ed. Jones,

1943, 184-85.

The smallest unit of measure derived from the human body is not the

inch (uncia) but the digit (digitus), the breadth of a finger. It formed the

base of the Italic foot (equivalent to 11.66 modern English inches) which

had sixteen digits. Four digits formed a hand (palmus) and four hands

formed a foot (pes). See Hultsch, loc. cit.

The tenacious survival in the modern Anglo-Saxon world of the

sedecimal graduation of the inch appears to suggest that this was also the

traditional way of subdividing the inches in medieval England. Yet this

is not born out by a reading of chapter 4 of Bede's De temporum ratione

(used as a standard text without rival in Carolingian times), as Charles W.

Jones brings to my attention. Here the inch is defined as being divided

into twelve and even twenty-four parts, a division retained in all of the

Carolingian glosses to this treatise, of which more than forty sets have

been examined by Jones (see Bedae opera de temporibus, ed. Jones, 1943,

loc. cit.). An analysis of Bede and other related texts may in fact suggest

a dichotomy in the approach to duodecimal and sedecimal systems,

between the theoreticians and the practitioners of measures and weights.

Charles W. Jones, in a personal letter, addresses himself to this subject

as follows:

"Bede (A.D. 725) treated weights and measures, primarily the divisions

of pound (libra) and ounce (uncia), in his classroom textbook, De temporum

ratione, chap. iv (Clavis patrum latinorum, n. 2320; see also Pat. Lat. XC,

cols. 699-702). Therein he recognized no other fractional principle than

duodecimalism, despite his addiction as an exegete to the concept of ten,

its square, and cube. He positively states that duodecimals are used not

only for weights (including numismetrics) but also for times (months,

hours, points, moments) and for lines, planes, and volumes of bodies

(Jones, 1943, 184.2-3; 185.26-28, 44-49).

"I have examined about twenty different sets of glosses for that

chapter, but only the following sets contain remarks pertinent to this

topic: Berlin MS 130, written A.D. 873 at Metz; Munich MS 18158, an

eleventh-century copy from Tegernsee of a ninth-century text; 21557, an

adaptation of 18158; Valenciennes MS 174, written about A.D. 840 at

Saint-Amand (duplicated in Brussels MS 9837-9840, saec. xii/xiii);

Vatican MS Rossi lat. 247, copied in the Loire region [Fleury?] about

A.D. 1018 from an exemplar of ca. 820. (The complete set of glosses from

the Berlin MS will be published in the forthcoming Corpus Christianorum

edition of Bede's Opera didascalica.) Bede's was the basic text on

the subject in Carolingian schools: about 150 codexes containing that

chapter are extant today. The masters seem to have disregarded Isidore's

treatment, Etymologiarum liber XVI, xxv-xvii, although it was in common

circulation. But they do quote Priscian's De figuris numerorum liber ii,

9-iii, 16 (ed. H. Keil, Grammatici Latini III, Leipzig, 1859, pp. 407-11),

sometimes verbatim and several times by name. Priscian dealt with

both decimals and duodecimals, but the glossators quite obviously tried

to eliminate decimalism by recasting his statements. Nor, with one

exception which I will mention, did these glossators introduce any

suggestion of sedecimalism.

"In short, the scholastic evidence points exclusively to duodecimal

measures in Carolingian as in early-English times.

"Such proof by silence might seem to refute use of sedecimals, but we

know that medieval scholasticism often was remote from practice. An

analogue is the void between Boethian and Gregorian music. I agree with

you that a master builder, with rod and plumbline, would be apt to

think in multiples of halves. The Metz glossator (Berlin MS) seems to

lend some support to this surmise. Bede had stated; Item decorporibus,

sive miliarium, sive, stadium, sive iugerum, sive perticam, sive etiam cubitum,

pedemve aut palmun partiri opus habes, praefata ratione facies. Denique et

in Exodo dimidium cubiti semis appellatur, narrante Moyse, quod habuerit

arca testamenti duos semis cubitos longitudinis, et cubitum ac semissem

altitudinis. ("Also you hold to the same fractions in measuring bodies,

whether miles, or stades, or acres, or rods, or even cubits, feet, or hands,

whenever you need to divide. In fact, in Exodus a half cubit is called a

`semis,' because, according to the statement of Moses, the Ark of the

Testament was two and a half cubits in length and a cubit and a half in

height.") The Metz glossator writes:

That the Plan of St. Gall was drawn to a scale of 1/16″:1′ was first

expressed by me in the French edition of the catalogue to the Council of

Europe exhibition dedicated to Charlemagne: "Le plan est entièrement

dessiné d'après une échelle, ou le 1/16e d'un pouce sur le parchemin

représente un pied sur le terrain. Converti en une relation d'unités

egales, cela signifie 1:192 (1/16 × 16 × 12 = 192/16), rapport de grandeur

qui approche l'échelle métrique du 1:200, mais qu'il ne faut aucunement

confondre avec celle-ci; puisque la relation 1:200 n'existait pas dans le

système métrologique médieval, où le pied est divisé en 12 pouces, et le

pouce en seize seizièmes" (see Charlemagne, oeuvre, rayonnement et

survivances [Dixième Exposition sous les Auspices du Conseil de

l'Europe], ed. Wolfgang Braunfels, Aix-la-Chapelle, 1965, 399).

I am delighted to find that in an article that became available to me

only after the present study was completed, Konrad Hecht had independently

come to the same conclusion: "Der Masstab 1:200 ist für einen

mittelalterlichen Plan zwar plausibel, aber doch irrig, denn dieser Masstab

setzt die dezimale Teilung des Fussmasses voraus. . . . Der St. Galler

Plan wurde nicht im Masstab 1:200, sondern im Masstab 1/16″:1′ entsprechend

1:192 gezeichnet" (Hecht, 1965, 187-88).

The figure 200 is not a natural break in a system that is based on

fractions of 12 and 16. It acquired meaning only after the adoption of the

metric system—a system of consistently graduated units of like dimension

which departed so radically from the chaotic, but deeply ingrained,

forms of mensuration which it supplanted that it could have been

inaugurated only under the auspices of a political revolution and enforced

by the mandate of an ensuing dictatorship. For a brief résumé of the

adoption of the metric system, see Arthur E. Kennelly, 1928, 12-27; for

a comprehensive, detailed account of the establishment and propagation

of the metric system and the operations that determined the meter and

the kilogram, see Favre, 1931 and Bigourdan, 1901.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||