INCREASING PROPENSITY FOR MODULAR

SPACE DIVISION IN PRE-CAROLINGIAN AND

CAROLINGIAN ARCHITECTURE NORTH OF

THE ALPS

The emergence of the square schematism in medieval

architecture depended on two crucial innovations in the

interrelation of the component spaces of the basilican

church:

1. The nave and the transept of the church had to be

given the same width, and

2. The width of the aisles had to be fixed to one-half

the width of the nave.

Without the first, the crossing could not form a square;

without the second, the modular division of the nave could

not be carried into the aisles. Both of these features

occurred separately in Early Christian times, but they were

not integrated then into a programmatic architectural

system.

An example of a church with nave and transept of equal

width is the Justinian basilica of the Nativity at Bethlehem

(if Hans Christ's interpretation of its plan is correct).[293]

In

several Christian churches of Ravenna—all without transepts—the

width of the aisles is fixed at one half, or approximately

one half, the width of the nave. Yet as we survey

Early Christian church architecture as a whole, we must

conclude that its truly distinguishing feature is not the

presence, but rather the absence of any fixed proportions.

Nevenka Petrović[294]

has made an illuminating study of the

proportions in churches of Ravenna and the adjacent

littoral of the Adriatic sea. In attempting to demonstrate

that these churches were laid out according to a system of

squares, as she set out to do, she has de facto illustrated the

fundamental difference between the layout of these later

Early Christian churches and the system of squares employed

in medieval architecture. The salient feature of the

Church of the Plan of St. Gall and its Ottonian and

Romanesque successors is that the squares control the

spacing of the arcades and therefore express the modular

layout of the plan in the elevation of the columns. The

divisions of Petrović's grids (fig. 166), by contrast, have no

relation whatsoever to the position of the arcade columns.

True, in some of the proto-medieval churches of Ravenna,

the length and width of the church exist in a state of

modular interdependency, but since this module does not

control the spacing of the columns, it is aesthetically of no

consequence.

I tend to agree with George Dehio that the square schematism

is essentially a "Germanic" contribution to Western

architecture for two reasons: first, because it is found

primarily in regions of relatively strong Germanic concentration,[295]

and second, because it is in these areas also that

we may detect its developmental antecedents. An early

medieval church exhibiting an incipient tendency toward

the use of the square as a module was Fulrad's church of

St. Denis, begun after 754 and consecrated in 775 (fig.

167).[296]

Its basic layout, if Formigé's interpretation is correct,

was developed within a grid of 6-foot squares which,

in contrast to San Giovanni Evangelista at Ravenna (fig.

166), determined not only the overall dimensions of nave

and transept, but also the interstices of its arcades. The

transept was seven 6-foot units wide, and thirteen long; the

nave was five units wide and fifteen long. The distance from

center to center of arcade columns was two units, and in the

middle part of the transept two cruciform piers establish a

square of five by five units. As yet we cannot speak of

square schematism, because the dimensions of the crossing

square are not mirrored anywhere else in the building, and

in particular not in the intercolumniation of the arcades. A

church that comes closer to this ideal is the Saviour's

Church of Neustadt-on-the-Main, after 768/69 (fig. 167).

The plan of this church together with other cruciform

churches of similar design built in early medieval times,

such as Pfalzel near Trier, and Metlach (both before 713),

may have formed a connecting link between square-divided

Carolingian basilicas of the ninth century and certain

cruciform churches of the fourth and fifth centuries, typical

examples of which are shown in fig. 144-146 and 148-149.

A grandiose variant of this church type, built as early as

380 by Emperor Gratian in his residential city of Trier,

rose in territory that later was part of the very core of the

Frankish kingdom—for every Carolingian to see! (Its

masonry survives to this day, incorporated in the fabric of

the Romanesque church that superseded it.) This is the

only pre-medieval church type where nave and transept

are of equal width, their intersecting bodies forming a

square—and one might indeed regard the fully developed

square schematism of the Carolingian period as a transference

to churches of basilican plan of a principle already

experimented with in pre-medieval times in the highly

specialized context of these Early Christian cross-in-square

churches.

[297]

The first Carolingian church to mark the developmentally

significant moment of the adoption of the

square schematism in a building of unequivocally basilican

design was the abbey church of Centula, 790-799, if

Irmingard Achter's reconstruction of this building is

correct (fig. 170).

[298]

Because of the scarcity of archaeological

data available on this important building, such an assumption

can neither be fully accepted nor convincingly

rejected. For the same reason it is impossible to ascertain

whether the interstices of the nave arcades were aligned

with these modules.

Modular adjustment between width and length of the

component spaces is clearly visible, however, in the abbey

church of Fulda (802-817).[299]

Its nave, measured from the

base of its western to that of its eastern apse, was exactly

four times its width (fig. 169). The dimensions of the

transept were identical with those of the nave. In the vast

body of literature devoted to Fulda—whose authors never

weary of citing the dependence of its design on that of Old

St. Peter's—this crucial aesthetic novelty has never been

pointed out, much less set into proper historical perspective.

We know nothing about the intercolumniation of

Fulda.

On the other hand, it is not possible to interpret Old

St. Peter's as having been developed within a grid of

identical squares—neither each volume by itself, nor any

volume in relation to a neighboring unit or to the whole of

the building mass. The architect who planned St. Peter's

employed instead a constructional system as classical in

concept as the modularity of the Carolingian churches

shown in figs. 144ff is medieval (see Born's analysis, fig.

170). He calculated the length of the longitudinal body of

the church by making use of the diagonal of a square with a

side equal to the width of the church, and developed the

overall length of the church in the same manner, with the

aid of the diagonal of the rectangle obtained by the preceding

method. This configuration, known as a √2

rectangle, is irrational, since the diagonal of a square is not

in any integral relationship to its sides (1: √2 = 1:1.414)

and therefore cannot be defined as an aggregation of an

integral modular value.

Hildebold's church of Cologne (ca. 800-819) was

composed wholly of equal squares: three in the transept,

four in the nave, one in the fore choir (fig. 172). If the

elevation of its nave walls was identical with that of the

church dedicated in 870, the piers of the arcades that

carried the clerestory walls would not have been in alignment

with this system.

The abbey church of Reichenau-Mittelzell, built by

Haito (806-816) is also developed within a modular grid of

squares, but the grid is irregular, and its existence, for that

reason, has been questioned. In evaluating this problem it

is important to distinguish the existence or nonexistence of

the concept of squares at Reichenau from the regularity or

perfection of its execution. The irregularity, in the angular

deviation of the walls from the grid (especially noticeable in

the eastern part of the church) is caused by special topographical

conditions. But no doubt can be entertained that

the concept exists. The shape of the fore choir and of the two

transept arms are almost a mirror image of the shape of the

crossing square, but the squares of the nave are slightly

oblong. Yet the principle of divisions is clearly there, and

the boundary between the two oblongs of the nave is

marked by piers, whose design differs from the columns

standing midway between them. In this feature St. Mary's

Church at Reichenau goes a step beyond even the Church

of the Plan of St. Gall, which has no such alternation in its

main supports.

In Hildebold's church of Cologne (fig. 172) the system

of squares finds clear expression in the west transept and

in the eastern fore choir, both of which are formed of squares

of identical size: three in the transept, one in the fore choir.

The nave is composed of four squares of like dimensions.

We know nothing about its elevation. If it was identical

with that of the church that was dedicated in 870, the piers

of the arcades which carry the clerestory walls would not

have been in alignment with the system of squares.

In the Church of the Plan of St. Gall the square schematism

attains its purest Carolingian form of expression (fig.

173). The basic unit is the 40-foot module of the crossing

square. The transept is formed of three such squares, the

fore choir of one, the nave of four and one-half; and the

dimensions of the crossing square are echoed even in the

Library and Vestiary. In St. Gall, moreover, the interstices

of the columns are in rhythmical alignment with the

squares. It is incomprehensible to me how this fact should

ever have been questioned. What the designer of this

church had in mind were arcades cutting deep into the

masonry of the nave walls (fig. 110) with their supports so

spaced as to give bodily expression to the sequence of

squares on which the Plan was based. This schematism is

a conscious and willed aesthetic principle. It is a fundamentally

different concept from that which produced the

low, narrowly spaced columnar orders of the Early Christian

basilicas of Rome (figs. 141 and 174). Contrary to what

Guyer, Reinhardt, and Reinle believe, it is an ingenious

anticipation of the square schematism of the Romanesque.

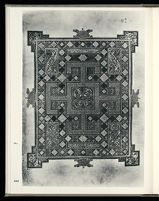

What are the historical preconditions of this propensity

for modular organization of space? Some clearly are functional.

Others may have to be traced to vernacular architecture.

For still others we shall have to reach, beyond the

boundaries of architectural history, into the field of book

illumination, where strong expression of modular modes

of thinking can be observed over a century before they

assert themselves in church building. Yet others, and perhaps

the most important of all, may have to be sought in

deeper and more general cultural levels.