I. 6

ORIGINAL OR COPY?

I.6.1

SOME TECHNICAL OBSERVATIONS

That the Plan of St. Gall is a "copy" rather than an

"original" must be inferred not only from the fact that its

maker refers to it as exemplata, i.e., "transcribed" or

"copied," but also from a variety of observations of a

technical nature, on which I have reported in a previous

study.[105]

A careful examination of the particulars of the

design of the Plan shows that it was traced, like a modern

"overlay," on pieces of parchment that were superimposed

upon a prototype plan. This is revealed by the following

facts:

1. The Plan does not show any underdrawing, as

would be inevitable in a layout of this complexity if it were

an original design.

2. The Plan exhibits in several places angular distortions

in the alignment of rectangular structures which are

characteristic of the displacement that occurs in tracing if

in the course of work the overlay inadvertently shifts a

few degrees from its initial alignment with the original and

this shift is not immediately corrected.

3. The drawing is full of minor inaccuracies and inconsistencies

that appear to be incompatible with the

exacting calculations prerequisite to the development of an

architectural drawing of this complexity; and it is rendered

in a fluid style not apt to be found in the work of a man

who went through the developmental labor of this demanding

task.

In what follows I shall elaborate on these observations.

ABSENCE OF UNDERDRAWING

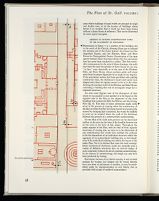

In figure 6, I have reproduced a detail of a well-known

architectural drawing of the thirteenth century which

renders the ground floor of the southern tower of Cologne

Cathedral.[106]

This design, which is a typical example of its

kind, shows how in laying out his plan a medieval architect

avails himself of an elaborate framework of auxiliary construction

lines and reference points which he presses into

the parchment with a fine stylus or silverpoint before

committing his drawing to ink. This constructional reference

work guides his eye as the drawing is being executed

and remains visible as an underdrawing, in the form of

thin grooves and fine prickings,[107]

in those portions of the

design which are not covered by ink in the final stage of the

work.[108]

In contrast to this, on the entire Plan of St. Gall there is

not a single line of this type to be found.[109]

The absence of

such auxiliary construction work is most conspicuous in

areas where buildings of equal width are grouped in single

and double rows, or in the interior of buildings whose

layout is so complex that it could not have been drawn

without a linear frame of reference. This can be illustrated

by some typical examples.

ABSENCE OF GUIDING CONSTRUCTION LINES

IN THE ALIGNMENT OF BUILDINGS

Reproduced in figure 7 is a portion of the building site

to the north of the Church, showing (from top to bottom)

the western end of the Outer School, the House for Distinguished

Guests, and the Kitchen, Bake, and Brew

House for Distinguished Guests. Examination of the open

spaces between these structures shows that the parchment

here has never been touched by a stylus. This had noticeable

consequences for the style of these drawings: the walls

that form the outer boundaries of these houses do not stay

"in line," most drastically so in the case of the Kitchen,

Bake, and Brew House, whose southern gable wall slants

away from its proper alignment by an angle of two degrees.

If the parchment surface had been provided with guiding

construction lines, the draftsman's hand could never have

slipped away from its regular course as far as it did when

drawing the southern walls of the Kitchen and Bake House,

converting a building that was of rectangular shape into a

trapezoid structure.

An even more flagrant case of the divergence of lines

meant to run parallel to one another is to be found on the

opposite side of the Plan in the alignment of the three

buildings that contain the Mill, the Mortar, and the Drying

Kiln (fig. 8). This kind of linear aberration might easily

occur in the process of copying when the translucency of

the skin on which the Plan was being traced was temporarily

marred by changing light conditions, but would be unlikely

to occur on an original where the quill of the draftsman

followed the grooves of a constructional underdrawing.

On the Plan of St. Gall such grooves can be discovered

neither on the recto in the form of the familiar furrows nor

on the verso in the form of thin ridges. Throughout the

entire expanse of the Plan, with its total of forty separate

structures of varying size, no trace is to be discovered of

any underdrawing that would have enabled the architect

to fix the dimensions of an individual structure within the

aggregate of its superordinate building site, or the boundaries

of the individual building site within the layout of the

entire Plan. Yet it is obvious that even the most accomplished

architectural draftsman could not assemble such a

variety of different structures into an over-all design of

such complexity without the aid of a guiding underdrawing.

In the absence of underdrawing, the design can only have

been produced by tracing.

Parchment, because of its relative opacity, is not an ideal

medium for tracing; but designs can be traced directly

from one sheet of parchment to another, as may be established

easily by experimentation in any library that is

provided with scraps of medieval manuscripts.[110]

ABSENCE OF GUIDING UNDERDRAWING IN THE

INTERNAL LAYOUT OF INDIVIDUAL BUILDINGS

An examination of the procedure followed in the construction

of the internal layout of the various buildings leads us

to the same conclusions. No building illustrates this fact

more persuasively than the Monks' Dormitory.

The Dormitory of the monks (fig. 60.A) accommodates a

total of seventy-seven beds. These are arranged in a

complicated pattern, resembling the letter U along the

two side walls, and the letter H (the U-pattern of the side

walls coupled) along the center of the building. One does

not have to look twice at this complex arrangement to

realize that it is impossible to distribute seventy-seven beds

in the manner just described within an area of such small

dimensions without a carefully calculated underdrawing.

Yet intricate as this layout is, the basic frame of reference

from which it was developed was ingeniously simple. It

consisted, most likely, of a simple grid of squares of the

type that I have reconstructed in figure 60.B, making use of

a measurement that serves as a basic unit value throughout

the entire Plan. In the development of the primary design

for such a layout, which must have been worked out before

the building was inked onto the original plan, such a

square grid may have been pressed into the parchment in

full detail. As the design was transferred to the master

sheet in the final assembly, there was no need to retrace

the square grid in its entirety, but a minimum of auxiliary

co-ordinates and prickings must, nevertheless, have been

laid down to enable the draftsman to fix the width and

length of each bed and to enter it in its proper place. Yet

nowhere in the interstices between the beds, on the Plan

of St. Gall, is there the slightest trace of such auxiliary

construction work. It is omitted from the internal layout of

the buildings shown on the Plan, and absent as well from

their external alignment.

ABSENCE OF CENTER POINTS IN THE

CONSTRUCTION OF CIRCLES

To construct a circle accurately, one must firmly anchor the

center leg of the compass in the material on which the

circle is to be drawn. The point of this leg has to penetrate

deeply enough to stay in place while the outer leg strikes

the circle. This is bound to leave a mark in the parchment,

and for this reason, on all medieval architectural drawings

on which circles have been drawn with the aid of a compass,

there is always a clearly visible depression or minute hole

in the skin, which reveals the point from which the circle

was struck. I refer once again to the drawing of the southwestern

tower of Cologne Cathedral as a typical case. It

contains two circular installations, a spiral stairwell built

into the masonry of the southwestern corner pier (fig. 9)

and a circular opening in the vault of one of the two inner

bays of the tower (the latter not reproduced here). In both

instances the hole that the center leg of the compass left in

the parchment as the circle was struck appears as a small

but clearly perceptible mark.

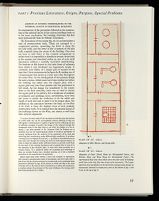

For purposes of comparison, five circular installations

shown on the Plan of St. Gall are reproduced in figures

10-13. Figures 10.A-B are the ambo and the baptismal font

in the nave of the church; figures 11.A-B are the two

circular towers that flank the Church to the west. Figure 12

is the enclosure for the hens to the south of the House of

the Fowlkeepers. No trace of the center point is found in

any of these drawings. Furthermore, these circles are too

inaccurate to have been constructed with the aid of a

compass. A circle drawn by compass forms a continuous

line of equal thickness, all points of which are equidistant

from the center point, as is well illustrated by the circle

that forms the outer boundary of the stairwell of Cologne

Cathedral. The circles reproduced in figures 12-13, on

the other hand, are drawn in successive motions of the

rotating hand, the beginning and end of which can still

be identified in many cases. Thus, for instance, close

inspection of the Plan of St. Gall shows that the outer

circle of the Henhouse (fig. 12) was drawn in five separate

strokes. The circle must have been started at the top

with a leftward motion and continued counter-clockwise

in four successive strokes, as I have indicated in figure 13.

As the draftsman passed through this course, he must

have rotated the two skins on which he worked in a

clockwise motion, a procedure which he repeated when

he entered the large explanatory title enclosed by the

circle that identifies this structure as the Henhouse. As he

approached the close of the circle, the draftsman discovered

that his terminal stroke was not in alignment with his

opening stroke, corrected this discrepancy with an additional

stroke which ran parallel to the first, but about 1 mm.

farther out.

While the circles are neither continuous nor accurate

enough to have been drawn by compass, they are far too

accurate to have been drawn without auxiliary construction

lines. As no such lines are to be discovered, we are once

more left with no alternative but to assume that the circles

were traced directly from an underlying original.

ANGULAR DISTORTIONS CAUSED

BY A SHIFT IN THE RELATIVE POSITION OF

ORIGINAL AND OVERLAY

My second argument in support of the contention that the

Plan of St. Gall is not an original rests on the observation

that in several areas the drawing exhibits angular distortions

that owe their origin to a shift in the alignment of original

and overlay. This observation is of crucial importance not

only for the question of originality but also because it gives

us a clue for establishing the sequence in which the buildings

were traced. We shall analyze this phenomenon in

detail in a subsequent chapter.[112]

For the present discussion,

suffice it to stress that we are faced here with a type of

linear deflection caused in the process of tracing when an

inadvertent shift between original and overlay is not

immediately detected and corrected. These deflections are

unlikely to occur on an original, as the underdrawing

would contain each individual building within the area

assigned to it, and would prevent the parallels from running

askew. The author of the Plan of St. Gall was able to

dispense with an elaborate system of auxiliary reference

lines, since for him the original itself performed the

function of the underdrawing. But as it was delineated on

a different surface, his drawing was subject to displacement

in relation to the original.

INCOMPATIBILITY BETWEEN THE FLUID

EXECUTION OF THE DRAWING AND

THE PRECISE DRAFTSMANSHIP REQUIRED IN THE

DEVELOPMENT OF THE ORIGINAL SCHEME

My last and final argument in favor of the proposition that

the Plan of St. Gall is not the original version of the scheme

is based on the observation of a profound discrepancy

between the fluid style of the drawing and the extraordinary

precision of construction that must have been employed in

the development of the original scheme—not only as the

dimensions of each individual building were established,

but also in the even more complicated task of fitting the

aggregate of structures into a coherent and scale-consistent

whole. No single line of the Plan has the mark of having

been drawn by rule or compass, as is the case with all the

principal lines of the pier and the tower of Cologne Cathedral (figs. 6 and 9). The draftsman of the Plan of St. Gall

rendered his lines with a broad quill in firm and fluent

strokes, the ease of which reveals the self-assurance of an

experienced hand; but being drawn without the aid of

supporting instruments, his rendering abounds with

inaccuracies and inconsistencies that are incompatible

with the precise draftsmanship required in the development

of the original scheme. About the nature of the latter more

will be said below. The observations presented here admit

of no other explanation than that the Plan of St. Gall is

a copy that was traced on sheets of parchment superimposed

upon a prototype plan. This raises the question

of the nature and origin of the prototype plan.

[ILLUSTRATION]

12. PLAN OF ST. GALL. HENHOUSE