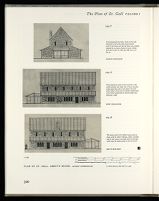

III.2.7

NOVITIATE & INFIRMARY COMPLEX IN

THE CONTEXT OF THE WHOLE PLAN

THREE SEPARATE CLOISTERS: AN ANSWER

TO MONASTIC STRATIFICATION

Conceptually, of course, this plan is an elaboration of the

layout of the monastery's principal church and claustrum,

and like the latter, it has its compositional roots in clearly

definable functional needs. Monastic custom required that

the novices be separated from the regular monks, the healthy

from the sick, and all of the religiosi from the family of

the monastery's serfs and workmen. This called for a

tripartite internal division of the claustral section of the

architectural plant as well as for a separation of this entire

aggregate of cloisters from an outer belt of service buildings,

in which the serfs and workmen were housed. The Plan of

St. Gall offers a brilliant answer to these needs: in axial

prolongation of the monastery church and the cloister of the

regular monks, a second church, of one-third the length of

the principal church, internally halved so as to be able to

serve the occupants of two further cloisters, ranged symmetrically

to either side of this sanctuary.

AXIALITY OF CHURCHES:

A PRINCIPLE INHERITED FROM EARLY

CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE

The placing of this complex on the axis of the main

church recalls a scheme that was in use in Early Christian

times in the eastern parts of the Roman empire, in such

places as the sanctuary of Menas in Abu Mina, Egypt,

fourth to fifth century,[301]

the cathedral of Gerasa (Jerash,

Palestine, ca. 400), and the church of St. Theodor, in the

same town, 494-96 (fig. 243),[302]

as well as an early Byzantine

complex at Ephesus, in Asia Minor.[303]

In all of these places

several churches were arranged in sequence, one behind

the other, along the same axis. The prototype of this

arrangement may have been the Constantinian Anastasis

Church at Jerusalem.[304]

A striking early medieval parallel

existed at St. Augustine's Abbey at Canterbury (fig. 244).

There, three churches, aligned east to west, were built in

Saxon times (SS. Peter and Paul, 598-616; St. Pancras,

before 613; St. Mary, about 618) and a fourth one at the time

of Abbot Wulfric (d. 1059).[305]

Undoubtedly, there were

others;[306]

the majority of the early medieval twin or cluster

churches, however, were laid out in lateral sequence or in

rather haphazard fashion.

GROUPING OF BUILDING MASSES: A

TRANSFER TO SITE ORGANIZATION OF PRINCIPLES

DEVELOPED IN BOOK ILLUMINATION

In the layout of the churches and cloisters of the Plan

of St. Gall another influence must be acknowledged: with

all of its classicism, it also has an amazing kinship with the

layout of some of the great illuminated pages found in

Carolingian and Iberno-Saxon manuscripts, in particular,

with those pages which illustrate the opening words of

each Gospel. Again, it may be futile to point at any one

specific example. Yet as one glances at the great decorated

page with the opening word of St. Mark's (Quoniam) in

the Book of Kells (fig. 245),

[307]

one cannot help but be

struck by the compositional similarities between the layout

of its dominant letter masses (stem and loop of the great

initial

Q) and that of the dominant architectural masses on

the Plan of St. Gall (aggregate of churches and cloisters):

their asymmetrical axiality, the manner of their framing by

secondary surrounding units (fig. 246). One cannot help

wonder whether there might not be some compositional

connection between the shape of the large inverted

L that

forms the second dominant motif of the

Quoniam-page of

the Book of Kells and the manner in which the guest and

service buildings to the south and west of the Church of the

Plan of St. Gall are pressed into an L-shaped sequence of

roofs that frame the dominant building masses of Church

and cloister in a similar manner. I am far from attempting

to establish any direct connection between the Plan of St.

Gall and the Book of Kells—the influence could have come

from common sources in a dozen different ways—but

should like to confine myself to the more general observation

that the comparison suggests that in the grouping of

the basic architectural masses of his monastery site the

architect may have drawn some inspiration from the

grouping of the letter masses on the great illuminated

manuscripts of his period.