III. 2

NOVITIATE AND INFIRMARY

III.2.1

TWO AUTONOMOUS CLOISTERS IN A

SYMMETRICAL BUILDING COMPLEX

The training of the novices and the care of the sick are

relegated on the Plan of St. Gall to a building complex (fig.

236) that stands separate from the houses of the regular

monks. It consists of two autonomous cloisters, each about

two-thirds of the surface area of the cloister of the regular

monks, laid out on either side of a double-apsed church

(ECLESIA) which is internally divided into a chapel for

the novices (facing east), and a chapel for the sick (facing

west). The axis of this church is a prolongation of the axis

of the main church. The entrances to the two respective

cloisters lie on the west, on either side of the apse of the

chapel for the sick, but since the apex of this apse touches

the apex of the eastern paradise of the main church, it

would have been impossible for any of the novices to stray

onto the grounds of the Infirmary, or for any of the sick to

enter into the cloister of the novices. Aesthetically, and

even in the functional layout of their spaces, these two

installations mirror each other in almost perfect symmetry,

yet in actual life their occupants were completely separated.

The church is 27½ feet wide and 110 feet long. Each of the

cloisters on either side of it covers a surface area of 75 × 90

feet, not counting the adjoining privies and hypocausts.

The entire complex of buildings was probably inscribed

into a plot of land 110 feet wide and 210 feet long.

III.2.2

TWO CHAPELS IN A CHURCH

INTERNALLY HALVED

The two chapels are designated by a single name ECCLESIA,

in capitalis rustica. They lie on either side of a

wall which divides the structure into halves, one chapel

opening into the Infirmary (istorü ingressus), the other into

the Novitiate (istorthic). Each chapel is divided into three

areas of approximately equal size: an area where the novices

and the sick are seated during the celebration of the divine

services, an intermediate section with two freestanding

"benches" (formulae) for a selected group of singers, and

the apse with the "altar" (altar̄; idem) raised one "step"

(grad) above the level of the other parts of the oratory.

Twenty-eight persons may be seated in each chapel:

twenty-two in the principal space of each chapel and six

on the freestanding spaces in front of the altar space. As in

the principal Church of the monastery, a clear distinction

is made between the seating of the general choir and the

space reserved for the voices of the specially trained singers,

who are in charge of the more difficult parts of the antiphon.[268]

III.2.3

NOVITIATE

LAYOUT OF THE CLOISTER

A hexameter written clockwise into the open space of the

cloister yard of the Novitiate informs us:

Hoc claustro oblati pulsantib· adsociantur[269]

In this cloister the oblates live with the

postulants

The oblati were youths offered to the monastery by their

parents.[270]

The pulsantes, literally "those who knock" (i.e., insist

on being admitted despite initial rejection and deliberate

discouragement) are novices on probation. The Rule of St.

Benedict prescribes a probation period of one year for each

novice.[271]

The cloister walks (porticus) with their arcaded galleries

enclosing an open pratellum or garden repeat on a smaller

scale the layout of the cloister of the regular monks. In both

there is no direct communication between adjacent rooms;

each opens separately onto the corresponding section of the

cloister walk. The designs of the arcades and the layout of

the pratellum are identical, and both elevations show in vertical

projection three arcades on either side of a central

passageway, a square area in the center of the pratellum with

a circle, which (to judge by analogy with the same symbol in

the monks' cloister) indicates the position of a savin tree in

the cloisters of the novices.

The cloister walks, in turn, give access to a U-shaped

tract of buildings, containing on the west a refectory

(refectorium) and a storeroom (camera); on the east, a

dormitory (dormitorium) and a warming room (pisalis); and

on the south, a sick room (infimort domus) and the apartment

for the master of the novices (mansio magistr eort).

Like the warming room of the regular monks, the warming

room of the novices is heated by a hypocaust with firing

chamber (camin') and smoke stack (exitus fumi). The sick

ward and the lodging of the master are heated with corner

fireplaces and have separate privies (exitus), each with two

seats. The dormitory has a privy (neces̄s̄) with six seats. The

beds for the novices are not shown on the Plan. If they were

placed in single file along the four walls of the room, there

would have been space for twelve beds; if they were

arranged in alternating sequence, parallel and at right angles

to the wall, the room could have accommodated about

twenty novices. Twelve is the number prescribed by Abbot

Adalhard of Corbie[272]

as the normal contingent of pulsantes

for the monastery of Corbie, and this may reflect a general

condition.

NOVICES AND THEIR SUPERVISORS

Hildemar[273]

classifies the youths of the monastery as

"children" (infantes), "boys" (pueri), and "adolescents"

(adolescentiores) according to their respective ages: "children"

up to the age of seven, "boys" from the age of seven

to fourteen, "adolescents" from the age of fourteen to

twenty-eight. Since every ten novices, according to Hildemar,[274]

had to have three to four supervisors with them at

all times, the Novitiate must have housed, along with the

novices, four or five regular monks. Some of those must

have slept in the Dormitory of the Novices. Others may have

shared the quarters of the master of the Novitiate. That the

latter was not the sole occupant of his apartment is suggested

by the size of his room and the fact that his privy has

two toilet seats. But the master's room could never have

held more than four or five beds besides his own. I call

attention to the interesting observation that the maximum

number of beds which could be installed in the novitiate

(twenty-six) does not exceed the seating capacity of the

chapel (twenty-eight), but is, rather, slightly below it.[275]

DIET AND CLOTHING

The abbot was responsible for the novices' food and

clothing. He had to provide them with fish, milk, and butter

and even with meat on the days of the higher religious

feasts. The younger boys received larger portions than the

adolescents. From the age of fifteen on, the novices renounced

meat entirely and their diet conformed to that of

the regular monks.[276]

Once each week, or at least once a

month, the youths were taken out into the open for games

and other forms of physical exercise.[277]

A complete account

of their clothing is given by Adalhard of Corbie:

These are what should be given to our aforesaid clerical canons who

have the special title of "knockers": in clothing, two white tunics

and a third of another color and four hose, two pairs of breeches,

two felt slippers, four shoes with new soles costing seven pence at

the cobblers, two gloves, two mufflers. These they receive every

year, but a cope of serge and fur and a mantle or bedcloth, or a

blanket, in the third year. All these should be taken from the

clothing which the brothers return when they receive new. And

they should select from the stock those garments which they think

are most useful to them. The other cowled garment—the tunic or

the cowl of serge from which the tunic can be made—will be issued

at the discretion of the prior.[278]

Adalhard also informs us that at Corbie some novices

were attached for special duty to other buildings: three to

the infirmary, one to the monks' laundry, and one to the

abbot's house.[279]

III.2.4

INFIRMARY

LAYOUT OF THE CLOISTER

The cloister containing the Infirmary lies on the northern

side of the double chapel:

Fribūs infirmis pariter locus iste par & ur

For the sick brethren similarly this place should

be established

The layout of its buildings corresponds in every detail to

that of the Novitiate. The warming room (pisal) and the

dormitory (dormitoriū·) lie in the east wing; the supply

room (

Camera) and the refectory (

Refectorium) in the west

wing—but the sequence is reversed, resulting in a complete

mirror reflection of the arrangement of the corresponding

spaces of the Novitiate. The room which in the Novitiate is

reserved for the sick (

infirmorum domus), is in the Infirmary

designated as "the place for those who suffer from acute

illness" (

locus ualde infirmorum). The dormitory of the Infirmary

(

dormitoriū·), then, must have served as sleeping

quarters for those afflicted with minor ailments, as well as

for the aged and infirm who made the Infirmary a permanent

home.

[280]

Its bedding capacity is the same as in the dormitory

of the novices: twelve beds, if they were ranged in single

file along the four walls of the room; about twenty, if they

were staggered. The apartment of the master of the

Infirmary (

mansio magistri eorum) and the "room for the

critically ill" each have a corner fireplace, but lack the other

facility shown in the corresponding rooms of the Novitiate,

the privy. This is one of the few genuine oversights of the

Plan and may be an inadvertent omission by the copyist.

[281]

CARE OF THE SICK:

THEIR DIETARY PREROGATIVES

The welfare of the sick was one of St. Benedict's primary

concerns:

Before all things and above all things care must be taken of the sick,

so that they may be served in very deed as Christ himself; for he

said: I was sick and ye visited me; and what ye did to one of these least

ones, ye did unto me. But let the sick on their part consider that they

are being served for the honour of God, and not provoke their

brethren who are serving them by their unreasonable demands.[282]

The abbot is admonished to take the utmost care that they

suffer no neglect. They are allowed to take baths, as often

as their condition requires and, in contradistinction to the

healthy monks, to whom the meat of quadrupeds is categorically

interdicted, the sick are allowed to eat meat when

they are very weak, "for the restoration of their strength,"

but must abstain from it as usual, as soon as they are

better.[283]

St. Benedict stipulates that the Infirmary be established

as a separate building (cella super se deputata) under the

supervision of a "God-fearing, diligent, and careful" master,

and Hildemar, in his commentary to this passage, says

that it ought to consist of several rooms in order to be

prepared for all exigencies; otherwise it might happen that

"one is ready to die, another about to vomit, a third in need

of eating, and a fourth compelled to take care of his natural

needs."[284]

As in the Refectory of the monks, the meal in this

refectory was accompanied by reading. If there were six

or less the text was read "in a subdued tone" (leniter); if

there were twenty, it was read "in full voice" (in voce).[285]

The Infirmary had to have its own oratory so that the sick

could attend mass.[286]

If they were too weak to be taken into

the oratory, the office was read to them in the sick ward.[287]

ADMISSION TO INFIRMARY

Admission to the Infirmary was neither a trifling nor a

purely private event. The first step was to appeal to the

abbot and the entire body of the assembled community for

entrance to the Infirmary. The

Concordus regularis, a monastic

consuetudinary of the end of the tenth century, based

partly on ancient English and partly on continental traditions,

defines the process as follows: When one of the brethren

is called upon to pay the debt of the common fragility

. . . he must declare to the abbot and the entire assembled

community the reasons of his distress, and then, after

having received their benediction, will be admitted to the

infirmary.

[288]

The Infirmary does not include space for physicians.

The quarters of these professionals are in an adjacent house,

to the north; it will be discussed in a later chapter.[289]

III.2.5

KITCHENS AND BATHHOUSES

Because of the detached location of their quarters, their

special diet, and their prerogative to take baths whenever

their condition required, the novices and the sick were

provided with their own kitchens and bathhouses. These lie

west of the Novitiate and the Infirmary, on either side of

the eastern paradise of the Church. They consist of two

oblong houses (22½ × 45 feet),[290]

each internally divided

into two equal halves, one containing the "kitchen" (coquina

eorundē), the other, "the bath" ([balnea]toriu, balneatorum

domus). The kitchens have a square stove, the baths a

central fire place, four corner tubs for bathing, and three

short wall benches (fig. 237). The Infirmary kitchen, besides

attending to the needs of sick monks, also provides the

food for the brothers who are being bled in the adjacent

House for Bloodletting (coqina eorunde & sanguine minuentium).

A thirteenth-century manuscript of the Chirurgia of

Roger of Salerno, contains an illumination of a medical

bath (fig. 238).[291]

The patient, as the accompanying text

explains, is soaking in the tub in order to heal "a rib bent

inward"; the instructions for the physician are that he

"anoints his hands with honey, turpentine, or pitch, then

presses and relaxes them at the hurt place, continuing

until the rib is restored to its proper place.[292]

III.2.6

SCHEME OF THE COMPLEX

ITS CLASSICISM

I am not aware of the existence of any other complex of

buildings of comparable designs, either earlier or later than

this one, nor of the existence elsewhere of two chapels,

placed end to end on the same axis, facing in opposite directions.

No other building of the Plan of St. Gall is as

classical in flavor as the complex which houses the Novitiate

and the Infirmary. Its classicism stands out against the rest

of Carolingian architecture with an intensity comparable to

that of the Aachen or Vienna treasury gospels against the

other schools of Carolingian book illumination. While no-one

has pointed at any classical prototypes (the question has

as yet not even been raised)—as one gazes at the consummate

order of its building masses laid out at right angles

around two open galleried courts on either side of a dominant

axial structure, terminating in apse and counter apse, one's

mind strays back to the grandiose layout of the forum of

Emperor Trajan with its double-apsed basilica and its

monumental courts (fig. 239).

ROMAN IMPERIAL PROTOTYPES

Constantine's basilica at Trier

Yet the answer to this puzzle may be closer at hand.

Excavations conducted after the close of World War II on

the grounds of the Constantinian Basilica at Trier, have

made it clear that the great audience hall in the palace of

Constantine the Great (figs. 240.A and B) had attached to

each of its two long sides an open galleried court.[293]

The

weight of the architectural masses differs distinctly (colossal

hall with comparatively narrow courts at Trier—large

courts with a comparatively narrow center tract of chapels

in the Novitiate and Infirmary complex) but the underlying

principles of composition are identical.

The porticus villa at Konz

The analogies are even stronger, if one turns from here

to a building, excavated early in 1959, 8 km. upstream from

Trier, on a high embankment formed by the confluence of

the river Saar with the Moselle: the imperial summer

residence of Konz, the ancient Contionacum.[294]

This large

and elegant porticus villa (fig. 241.A and B), of an overall

length of 84 m. and an overall width of 38 m., consisted

of a central audience hall flanked on either side by an open

court that had attached to its outer side two massive cross

wings, with dwelling units, view terraces and a bath.

Lengthwise these units were connected by two magnificent

porticos. Admittedly, even here the analogies tend to

become evasive if one begins to focus on details: the courts

are not colonnaded. Nevertheless, the two buildings make

it forcefully clear that the Novitiate and Infirmary complex

of the Plan of St. Gall, with its two open courts symmetrically

laid out to either side of a dominant center block

had its historical roots in Roman palace architecture.

Other porticus villas in the territory of the

Salian Franks

The porticus villa at Konz is not the only example of its

kind north of the Alps. In the early 1930s of this century

the Dutch excavator W. C. Braat unearthed on a hill

called Kloosterberg near Plasmolen, parish Mook, in the

province of Limburg, Holland, the foundations of a

Roman villa, which he interpreted to have been composed

of a large central hall, flanked by two open courts with

living ranges grouped around them on the three remaining

sides (fig. 242).[295]

Another luxurious Roman porticus villa

of this type had been excavated as early as 1904-1906, at

Wittlich on the Lieser river, a northern tributary of the

Moselle.[296]

This, however, exhausts our knowledge of this

building type. No other Roman villas or palaces of comparable

plan appear to have been found anywhere else in

the Roman Empire; and it may be significant for our

problem that the only four examples known to date are

located within an air distance of no more than 62 (Wittlich),

75 (Trier and Konz) and 87 (Kloosterberg) miles respectively

from the Palace at Aachen, where the details for the

scheme of the Plan of St. Gall were worked out.

Could they still be seen in Carolingian times?

Of course, this raises the question whether any of these

presumptive Roman prototypes could still be seen in

Carolingian times. For the porticus villa at Konz and the

audience hall of the imperial palace at Trier this question

must probably be answered in the affirmative. The villa

at Konz had walls of considerable height, even as late as

the seventeenth century, as is attested by drawings made

of its ruins at that period.[297]

The audience hall of Constantine,

although internally divided into a variety of smaller

spaces and externally submerged in an agglomeration of

other extraneous accretions, remained in constant use, and

its masonry survived even the holocaust of Allied carpet-bombing

in August 1944.

Historians of Trier have pointed out that the worst

damage inflicted to its Roman buildings was caused not by

the havoc of the Frankish conquest (or any of the other

barbarian incursions of the Moselle river valley), but

through their ruthless exploitation, by their own medieval

and postmedieval guardians, who used these treasures as a

source for building materials, or ceded them for that use to

others. The Roman amphitheater of Trier remained intact

until the thirteenth century, when it was deeded to the

monks of Hemmerode by the Bishop of Trier (1211) with

leave to use its stones for the construction of buildings on a

vignard they had acquired outside the walls of the city.[298]

The Barbara baths were used for residential purposes by a

local noble family, and in this manner preserved throughout

the better part of the Middle Ages. It was only after

the last descendant of that family had died, in the fourteenth

century, that this building was abandoned and

surrendered to the citizens of Trier as a free-for-all quarry.

What its medieval pilferers left behind was finally blown

up by explosive charges in the seventeenth century and

used for the construction of a college for Jesuits.

[299]

The

ability to survive the storms of the Germanic migration was

strongest of course in the walled and fortified towns, which

continued to serve as administrative centers for both the

church and the secular powers. But even in the country the

continuity of life was not so radically broken as was

formerly believed. In an illuminating review of this

problem, based on a study of the distribution pattern of

Roman and Frankish cemeteries, Kurt Böhner could

demonstrate that large segments of the Roman and Gallo-Roman

populations in the Moselle River basin continued

to carry on their peaceful work, under their new Germanic

rulers, living side by side with them on interspersed

holdings.

[300]

In the light of these conditions there appears to be no

reason whatsoever to question the survival, in Carolingian

times on Frankish territory, of buildings (albeit in ruinous,

but nevertheless in recognizable condition) of the type of

the imperial villa at Konz or to doubt the possibility of an

influence of this building tradition upon the creation of the

layout for the Novitiate and Infirmary complex of the

Plan of St. Gall.

III.2.7

NOVITIATE & INFIRMARY COMPLEX IN

THE CONTEXT OF THE WHOLE PLAN

THREE SEPARATE CLOISTERS: AN ANSWER

TO MONASTIC STRATIFICATION

Conceptually, of course, this plan is an elaboration of the

layout of the monastery's principal church and claustrum,

and like the latter, it has its compositional roots in clearly

definable functional needs. Monastic custom required that

the novices be separated from the regular monks, the healthy

from the sick, and all of the religiosi from the family of

the monastery's serfs and workmen. This called for a

tripartite internal division of the claustral section of the

architectural plant as well as for a separation of this entire

aggregate of cloisters from an outer belt of service buildings,

in which the serfs and workmen were housed. The Plan of

St. Gall offers a brilliant answer to these needs: in axial

prolongation of the monastery church and the cloister of the

regular monks, a second church, of one-third the length of

the principal church, internally halved so as to be able to

serve the occupants of two further cloisters, ranged symmetrically

to either side of this sanctuary.

AXIALITY OF CHURCHES:

A PRINCIPLE INHERITED FROM EARLY

CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE

The placing of this complex on the axis of the main

church recalls a scheme that was in use in Early Christian

times in the eastern parts of the Roman empire, in such

places as the sanctuary of Menas in Abu Mina, Egypt,

fourth to fifth century,[301]

the cathedral of Gerasa (Jerash,

Palestine, ca. 400), and the church of St. Theodor, in the

same town, 494-96 (fig. 243),[302]

as well as an early Byzantine

complex at Ephesus, in Asia Minor.[303]

In all of these places

several churches were arranged in sequence, one behind

the other, along the same axis. The prototype of this

arrangement may have been the Constantinian Anastasis

Church at Jerusalem.[304]

A striking early medieval parallel

existed at St. Augustine's Abbey at Canterbury (fig. 244).

There, three churches, aligned east to west, were built in

Saxon times (SS. Peter and Paul, 598-616; St. Pancras,

before 613; St. Mary, about 618) and a fourth one at the time

of Abbot Wulfric (d. 1059).[305]

Undoubtedly, there were

others;[306]

the majority of the early medieval twin or cluster

churches, however, were laid out in lateral sequence or in

rather haphazard fashion.

GROUPING OF BUILDING MASSES: A

TRANSFER TO SITE ORGANIZATION OF PRINCIPLES

DEVELOPED IN BOOK ILLUMINATION

In the layout of the churches and cloisters of the Plan

of St. Gall another influence must be acknowledged: with

all of its classicism, it also has an amazing kinship with the

layout of some of the great illuminated pages found in

Carolingian and Iberno-Saxon manuscripts, in particular,

with those pages which illustrate the opening words of

each Gospel. Again, it may be futile to point at any one

specific example. Yet as one glances at the great decorated

page with the opening word of St. Mark's (Quoniam) in

the Book of Kells (fig. 245),

[307]

one cannot help but be

struck by the compositional similarities between the layout

of its dominant letter masses (stem and loop of the great

initial

Q) and that of the dominant architectural masses on

the Plan of St. Gall (aggregate of churches and cloisters):

their asymmetrical axiality, the manner of their framing by

secondary surrounding units (fig. 246). One cannot help

wonder whether there might not be some compositional

connection between the shape of the large inverted

L that

forms the second dominant motif of the

Quoniam-page of

the Book of Kells and the manner in which the guest and

service buildings to the south and west of the Church of the

Plan of St. Gall are pressed into an L-shaped sequence of

roofs that frame the dominant building masses of Church

and cloister in a similar manner. I am far from attempting

to establish any direct connection between the Plan of St.

Gall and the Book of Kells—the influence could have come

from common sources in a dozen different ways—but

should like to confine myself to the more general observation

that the comparison suggests that in the grouping of

the basic architectural masses of his monastery site the

architect may have drawn some inspiration from the

grouping of the letter masses on the great illuminated

manuscripts of his period.

III.2.8

RECONSTRUCTION

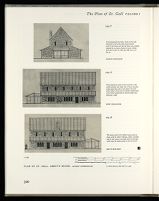

The reconstruction of the Novitiate and Infirmary (figs.

247-250) complex poses no problems. The round apses of its

two chapels, its arcaded cloister walks, its Roman hypocaust

system leave no doubt that it was to have been a masonry

structure. In determining the heights of these buildings, we

have based our calculations on the minimum requirements,

as we did in the elevation of the Church. The arcades of the

cloister walks would have had to be sufficiently high to give

head clearance; the windows of the two chapels, to be above

the line that touches the roof of the contiguous cloister

walks. We need not assume a clerestory between the roofs

of the cloister walks and the contiguous quarters of the

novices and the sick, since the exterior walls of these

structures would have offered ample space for the installation

of windows.

The Kitchen and Bathhouse have been reconstructed as

timber-framed buildings. Even in considerably later periods

ancillary structures of this kind were, as a rule, constructed

in timber.