SETBACK AND RE-EMERGENCE

On the preceding pages I have shown that the square

schematism appeared in western architecture neither as

abruptly and nor with as few historical preconditions as was

formerly thought. This raises the question: why, once

conceived, did it so suddenly disappear, not to re-emerge

until almost two centuries later?

The answer to this, I think, is relatively simple. The

square schematism, in the highly sophisticated and accomplished

form, which it attained in the layout of the Church

of the Plan of St. Gall, was born within the conceptual

framework of a building that had an overall length of no

less than 300 feet and for that reason could readily be

divided internally into a sequence of 40-foot squares. When

in the revisionary textual titles of the Plan it was suggested

that the church be reduced to a length of 200 feet and that

the columnar interstices be shortened from 20 to 12 feet,[312]

the modular order of the original layout was demolished.

There is no evidence to suggest that this reduction in size

was conditioned by structural or aesthetic considerations.

The change occurred as has been shown,[313]

at more or less

the same time—and probably for the same reasons for

which—the abbot of Fulda was deposed for overtaxing the

spiritual and economic resources of his monastery with the

construction of a church considered by his monks as being

outrageously large. In this historical climate the dimensions

of the Church of the Plan of St. Gall, as laid down in the

drawing, could no longer be considered prototypal. The

grandiose scale of the original concept had received a

shattering blow in the neo-asceticism of the monastic reform

movement, and, in consequence, was abandoned.

The political chaos that followed the reign of Louis the

Pious offered no opportunities for a return to the earlier

concepts. Their renascence had to await the political and

economic consolidation that was brought about in Germany

by the house of the Saxon kings, and in France by the rising

power and importance of the dukes of Normandy that

peaked in the conquest of England.

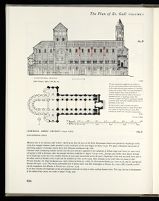

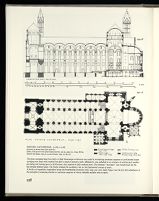

The steps that lead to the re-emergence of square

schematism in Ottonian and Norman architecture are well

known and need not be reiterated. They are marked by

such highlights of medieval architecture as St. Michael's

Church at Hildesheim, 1010-1033 (fig. 188); the Abbey

Church of Jumièges, 1040-1061 (fig. 189); and the second

stage of the imperial cathedral of Speyer, ca. 1080-1106

(figs. 186 and 190).

St. Michael's at Hildesheim had a total length of 230 feet

and was internally composed of a sequence of seven

modules 30 feet square plus an apse with a radius of 20 feet

(fig. 188).[314]

One could not wilfully construct a more convincing

mirror-image of the modular square division of the

Church of the Plan of St. Gall (figs. 61 and 173).

I do not know of the existence of any accurate measurement

studies of the Abbey Church of Jumièges (10401067).

But from the plans of Martin du Gard[315]

and of

Lanfry[316]

one gains the impression that it might have been

based on a modular sequence of 35-foot squares, four of

those composing the nave, one the crossing, one the fore

choir, and one half the apse, for a total of six and one-half

squares.

Whether or not the renascence of these modular concepts

at Hildesheim and Jumièges has any direct connection with

the Plan of St. Gall is impossible to say. The discussion of

this subject has suffered from the fact that until very

recently the square schematism even of the Church of the

Plan of St. Gall had been questioned.[317]

Yet the similarities

can hardly be overlooked. As in the Church of the Plan of

St. Gall (fig. 61), so in Hildesheim and in Jumièges the

general dimensions of the principal spaces were calculated

as multiples of the crossing square. In both of these churches

this modular division was aesthetically underscored by a

rhythmical alternation of light supports with heavy supports,

the latter marking the corners of the module, the

former rising in the interstices between them. The system

has two isolated Carolingian precursors in the abbey

churches of Werden (dedicated 804)[318]

and Reichenau-Mittelzell

(consecrated in 816)[319]

but becomes a governing

principle of style only in the Ottonian period, starting with

the abbey church of Gernrode (961-965)[320]

and leading

from there in successive steps of refinement through the

magnificent series Hildesheim[321]

—Jumièges—Speyer. A

feature of primary developmental implications—completely

overlooked in all authoritative studies on the Abbey Church

of Jumièges—were the great diaphragm arches that spanned

the nave crosswise, rising from shafts attached to every

alternate pier.[322]

Aesthetically this is a first attempt to visually connect the

alternating support articulation of the nave walls with the

aid of a bold transverse member reaching full width across

the space of the nave as well as full height into the roof of

the structure. The diaphragm arch has been variously derived

from Roman,[323]

Syrian,[324]

Mohammedan,[325]

and

Italian[326]

sources; but its prototype is much closer at hand;

in the masonry arches that frame the area of intersection in

churches with nave and transept of equal height, and

establish in the transepts of these churches a modular cross

division of space that precedes that of the nave by centuries

(Church of the Plan of St. Gall, 816-17; Hildebold's

Cathedral of Cologne, after 800 and before 819; and perhaps

even the abbey church of St. Riquier, 790-799).[327]

The ultimate prototype of the diaphragm arch is, of course,

the triumphal arch of the Early Christian basilica[328]

and

the testing ground for its migration from the transept into

the longitudinal body of the church are the aisles, where

precocious modular cross division by means of transverse

arches appear as early as the beginning of the ninth century

(Werden-on-the-Ruhr, dedicated by Bishop Ludger in 804

and Reichenau-Mittelzell, consecrated by Bishop Haito in

816).

The transept of the Cathedral of Speyer looks as though

it might have been conceived as a triad of 50-foot squares.[329]

The spacing of the piers in the original building (Speyer I,

constructed between 1030 and 1061) did not perpetuate

these dimensions; and when the nave, between 1080 and

1106 (Speyer II) was covered by groin vaults, mounted on

arches rising from shafts attached to every alternate pier,

this resulted in a sequence of oblongs rather than squares.

This variance in modular shape and size is an impurity of

minor importance; the epochal historical advance achieved

in Speyer was that the modular division of the ground floor

was here, for the first time, embodied in an all-pervasive

system of shafts and arches that divided the space lengthwise

and crosswise as well as in its entire height into a

modular sequence of clearly definable cells or bays. Once

this point was reached, the walls between the rising shafts

and arches could be perforated—and were in fact transformed

progressively into that intensely skeletal armature

of shafts and arches that led to the formation of the Gothic.

The self-contained and divisive vaults that covered the

bays of Romanesque and Gothic churches—firmly set off

against each other by their strong relief of framing arches

and ribs—were bound to strengthen the modular organization

of the spaces they covered. Yet they cannot by any

stretch of imagination be interpreted as a technical precondition

of that concept. Modular area division—as has

been made abundantly clear by the examples here cited—

preceded modular vault construction by centuries and

reached far beyond the realm of architecture into the layout

of the decorative pages of Christian service books. It has its

roots in a cultural frame of mind, not in technical conditions.

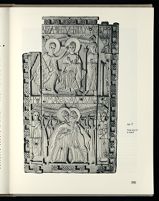

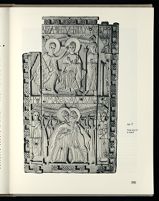

[ILLUSTRATION]

190.X GENOELS-ELDEREN DIPTYCH

190.Y

Shown same size

as original

BRUSSELS. MUSÉES ROYAUX D'ART ET D'HISTOIRE

[by courtesy of the Musées Royaux]

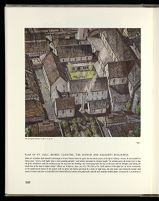

The monumentality of architecture in concept, execution, and fabric

may tend to overwhelm the scale of, and make distant, those objects that

men once handled and used in their daily pursuits. Tools, books, jewelry,

harness trappings, weapons, liturgical objects—with few exceptions they

are gone from us. The survivors, many of them precious then, as now,

lie in museums, remote from the purposes of their makers and rendered

exotic by their scarcity. Thus, the integration in spirit of such intimate

objects with monuments of architecture is somewhat difficult to achieve.

The many handicrafts that provided embellishment to daily life in a

monastic community such as was proposed by the Plan of St. Gall, has

been but lightly touched upon in this study. That works of art and

adornment were important to the community is undisputed. The Plan

has accommodations for making weapons and associated equipment,

saddlery and presumably other harness tack, and goldsmithing. Silversmiths,

lapidaries, and enamellers may have worked with armourer and

swordsmith. These crafts were housed with other facilities for more

ordinary work, in a pair of buildings in the southwestern tract of the

presumed site. Lay artisans were intended to reside in the community,

as is evidenced by comprehensive housing provided in the Plan.

Crafts that enhanced the praise of God by ornamentation of books,

vestments, and liturgical objects to assist in worship, were proper

activities for monks. Most notable were manuscript copying and

illumination, and ivory carving was likely among them. It is not

referred to specifically on the Plan of St. Gall, probably because its

execution did not require special facilities such as forges, smelters, and a

welter of noisy tools. The work of the ivory carver, silent and delicate,

often closely connected with all aspects of bookmaking, could be done

in a scriptorium, in company with scribes and illuminators.

The illustrated book cover is closely related to illuminations of the

Godescalc Gospels (781-783), earliest of the Court School manuscripts.

It has the same flatness of relief, the same delicate linearity, clearly

distinguishing it from the softly rounded forms and classicizing drapery

style of the later ivories of this school. The model must have been an

Early Christian ivory of Coptic or Syrian origin and representing a

style widely diffused in Merovingian Europe.

The front cover of the diptych shows Christ standing on the asp and

basilisk, flanked by two angels. The back cover displays the Annunciation

(upper register) and Visitation (lower register). Both covers are

pieced from several ivory plaques of different sizes. The work is

perforated and may have been mounted on a foil of gold leaf. The eyes

are inlaid lapis; interlace and step-patterns of the frames are clearly

influenced by insular art and stand in strong contrast to the perspective

illusionism of the two scenes. For references, see Braunfels, KARL DER

GROSSE, WERK UND WIRKUNG (exh. cat.), No. 534, pp. 345-46.

END OF PART II