MODULAR AREA DIVISION: AN INTRINSIC

FEATURE IN THE LAYOUT AND DESIGN

OF ILLUMINATED PAGES IN HIBERNO-SAXON

AND CAROLINGIAN MANUSCRIPTS

The modular bay division that governed the construction

of the Germanic house from the first millennium B.C.

onward was not the only source for the appearance of

modular relationships in Carolingian church architecture. It

may, in fact, take second place when weighed against

another influence, which reflects an attitude of mind more

than a constructional necessity. An organization based on

modules is one of the distinguishing features of the layout

of the illuminated pages of Hiberno-Saxon and Carolingian

manuscripts.

Figures 179.A and 179.B show how the artist of the Lindisfarne

Gospels set out to decorate the large cruciform page

that forms the frontispiece (fol. 2v) to this remarkable book

(fig. 178).[304]

The principal motif is a square-headed cross

framed by a narrow band and decorated internally with a

key pattern. In the field between the arms of the cross and

the outer frame of the page, there are four panels with step

patterns, two square ones on the top, two of oblong shape

at the bottom. The background is filled with an intricate

design of interlace. The page is framed by a strip of interlaced

birds, held in by narrow bands which terminate at

each of the four corners in an ornamental knot.

An analysis of the construction method used in setting

out the design of this page shows that all the basic divisions

are multiples of the width of the framing bands. The basic

values are 5 · 6 · 7 · 12 (fig. 179.A). The squares of the cross

measure 12 · 12; the panels in the fields above and beneath

the arms of the cross are 10 · 10 and 10 · 25. I feel certain

that a system of linear coordinates, such as is shown in

figures 179.A and B, was laid out on the page, by means of

either lines or prickings before the artist entered the

decorative details. In certain places where the design was

very intricate, such as the panels above and under the arms

of the cross with their complicated step patterns (fig. 180.A),

the illuminator actually drew out the lines with the point

of a fine stylus. This is visible on the opposite side of the

sheet (fol. 2r) as a grid of delicately protruding ridges (fig.

180.B).[305]

I have shown in figures 180.C and D how this system was

worked out. First, the illuminator divided the square

internally into sixteen subordinate squares by the method

of continuous halving. Then he divided each subordinate

square into nine base squares through internal tri-section.

This furnished him with all the desired linear co-ordinates

for the lozenge, cross, and step patterns with which these

squares are decorated (fig. 180.A). The same or similar

methods were used in all other ornamental pages of the

manuscript, and also in the layout of the canon tables (fol.

10r-fol. 17r).

Figures 182.A, B, and C give an analysis of the design

of the great cruciform page on fol. 138v that precedes the

Gospel of St. Luke (fig. 181).[306]

This page has as its main

motif a cross with T-shaped arms, filled in with a background

of interlaced patterns; the spaces around the cross

are filled with an animal interlace. The entire decoration of

this page is laid out on a system of squares, each side of

which is four times the width of the framing band. The

page measures thirteen units across and seventeen units up

and down. The transverse axis of the cross is laid out in

the sequence:

4 · 12 · 4 · 12 · 4 · 12 · 4

the vertical axis in the sequence:

4 · 4 · 4 · 12 · 4 · 12 · 4 · 12 · 4 · 4 · 4

The protruding knots at the corners and in the prolongation

of the two intersecting axes of the page are inscribed

into a marginal area seven units wide.

These principles of modular book design so typical of

Hiberno-Saxon art were inherited by the continental

Carolingian illuminators. Figures 183.C and D are a design

analysis of two of the canon tables of the Ada Gospels, fol.

6v and fol. 8v (figs. 183.A and B).[307]

The layout of these

tables varies. Some have four arcades, others have three.

As in the Lindisfarne Gospels all the internal subdivisions of

these pages are calculated as multiples of the width of the

framing bands. In both tables the design is suspended in a

square grid composed of 4 × 4 base units.

On fol. 6v (figs. 183.A and C) the bases of the columns

and their interstices are calculated in the sequence:

14 · 2 · 14 · 2 · 14 · 2 · 14 · 2 · 14

the column shafts and their interstices in the sequence:

4 · 12 · 4 · 12 · 4 · 12 · 4 · 12 · 4

The columns are inscribed into a grid of 16 × 19 squares,

the arches into a 9 × 19-square grid.

The canon arch on fol. 8v (figs. 183.B and D) has only

three columns. It is based on the same grid pattern. The

bases of the columns are calculated in the sequence:

16 · 4 · 16 · 4 · 16 · 4 · 16

the column shafts and their interstices in the sequence:

4 · 16 · 4 · 16 · 4 · 16 · 4

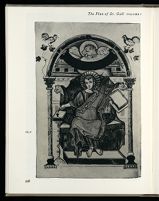

Figures 184.A and B show that the same method of construction

is used in the layout of the arch which frames the

figure of St. Mark on fol. 59v of the Ada Gospels. The basic

unit is a square, three times the width of the framing bands.

The columnar section is a square, 20 × 20 units; the arch

section, an oblong of 9 × 20 units.

The square grid affects the layout of the page, but not the

design of the figure of the Evangelist. This latter is clearly

patterned after a Byzantine model. The conflict between

the corporeal emphasis of the classical design, and the

tendency of the northern medieval illuminator to subject

the borrowed image to linearism and geometricity provoked

a developmental dialectic in which the ability to absorb

classical influences with increasing strength, in successive

stages, is preconditioned by a partial rejection and successful

transformation of those absorbed in a preceding phase.

In the period of the Romanesque, as a consequence of this

dialectic, solutions are obtained in which southern corporeality

and northern abstraction enter into a state of

balance (fig. 185). In like manner in the field of architecture,

southern masonry tradition fuses with northern frame

construction in a marriage in which the two component

traditions are matched with consummate perfection (fig.

186).

The square schematism is the primary organizing agent

in this development. It helps to disassemble the large

corporeal spaces of the Early Christian basilica, and to

arrange its parts in modular sequences that could be

vaulted. It determines the take-off points for the rising

shafts and arches that were needed to carry the vaults.