II.3.3

EXTENDED EASTERN ALTAR SPACE

(FORE CHOIR)

When the fore choir was introduced between the transept

and the eastern apse of the church, the T-shaped plan of

the Early Christian basilica was transformed into a Latin-cross

plan (crux capitata). The origin and dissemination of

this feature forms one of the most fascinating chapters in

the history of medieval architecture.[221]

Contrary to Georg

Dehio's belief two generations ago, the Latin-cross plan

is not a Carolingian invention. It came into use early in

the fifth century[222]

as a fusion of the longitudinal basilica

and the cruciform central plan of buildings traditionally

associated with Christian martyria.[223]

The cruciform plan

is well established in such buildings as the first church of

St. John in Ephesus, built in the fourth to fifth century

(fig. 142);[224]

the Nativity Church in Bethlehem, built by

Justinian in the sixth century (fig. 143);[225]

the cruciform

basilicas of Thasos in Macedonia (figs. 144 and 145)[226]

and of

Salona in Dalmatia (fig. 146).[227]

In Merovingian France the form appears as early as 577,

when the Greek-cross plan church of Ste.-Croix-et-St.Vincent

at Paris (completed by King Childebert in 558)

was transformed into a Latin cross by the addition of

aisles.

[228]

The new form thus created was subsequently

copied in several other Neustrian churches, most notably,

perhaps, in the church of Corbie.

[229]

Dehio was of the opinion that the Latin-cross plan owed

its rise to practical considerations, namely the need for

more choir space for the worshiping monks. Graf stressed

the commemorative, funerary significance of the centralized

cruciform development of the eastern end of the church.

In a recent review of this controversy George H. Forsyth

has pointed out that these two theories need not preclude

each other and that a vast body of new material, made

available since the time Dehio and Graf discussed these

problems, tends in fact to corroborate both opinions.[230]

In the historical evaluation of this important architectural

motif, a sharp distinction must be made between its origin

and occasional appearance in Early Christian times and its

prevalence everywhere during the Carolingian period.

Practical considerations must have played a decisive role

in its adoption at the time of Charlemagne. The cult of

relics, which had introduced into the church a multiplicity

of altars, made it impossible for the service of the high

altar to expand into the nave or the aisles of the church.

Few monasteries had fewer than 100 monks, and some had

as many as 300 or 400. Without the insertion of a fore choir

between transept and apse, there would have been insufficient

space for the monks participating in the service. At

the same time it cannot be denied that because of its

association with the relics of the Patron Saint of the church,

the high altar had acquired an intrinsically funerary significance—another

historical incentive for the absorption in

the basilican scheme of the cruciform arrangement of the

centralized paleochristian martyria. Lastly, it is also quite

clear that the Carolingian architects who struggled with

the development of the Latin-cross plan could hardly have

been blind to the exciting aesthetic implications of a

fusion between the basilican and the central plan.

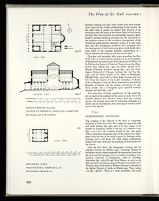

Churches with extended altar space preceding the Plan

of St. Gall, as I have already pointed out in my discussion

of Reinhardt's reconstruction of the Church of the Plan,[231]

of

St. Gall are the Saviour's Church of Neustadt-on-the-Main,

shortly after 768/69 (fig. 133); the abbey church of St.

Riquier (Centula), between 790-99 (fig. 135); the Carolingian

Cathedral of Cologne, between 800 and 819 (fig.

139); and the abbey church of St. Mary at Reichenau-Mittelzell

(fig. 134), built by Abbot Haito between 806 and

816. Even the church of the model monastery of Inden,

built by Emperor Louis the Pious between 815 and 816 for

Benedict of Aniane and his chosen community of only

thirty monks, had a rectangular space inserted between

transept and apse (fig. 147).[232]

The innovative aesthetic significance of this motif lies

not so much in the addition of the space as such, but in the

modular alliance into which it enters with the crossing

square, the transept arms, and by extension, although at a

slower rate of development, with the square division of the

nave of the church.