II.3.2

LENGTH OF THE CHURCH

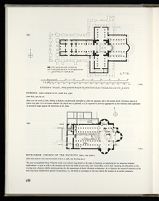

The Church of the Plan of St. Gall is chronologically not

the first monastic church of this order of magnitude but

probably the third or fourth. The earliest was the Abbey

Church of Fulda, in the form which it obtained under

Abbot Ratger between 802-817 (fig. 138). It had a clear

inner length of 98.00 meters (321 modern English feet).[211]

The second was probably, although not demonstrably so,

the monastery church of St. Peter's and St. Mary's in

Cologne (fig. 139), founded by Bishop Hildebold (d. 819),

which measured 91.20 meters internally from apse to apse

(300 Carolingian feet, calculated at 1 foot = 30.04cm.)[212]

The third was the original church of the Plan of St. Gall,

as rendered in figure 140 (prototype plan made in 817;

copy for Abbot Gozbert between 820 and 830). The fourth,

if Groszmann's analysis of this building is correct, was the

Abbey Church of Hersfeld, built between 831 and 850.

Together with its west-work, it measured 102.85 meters

(339 modern English feet).[213]

Abbot Ratger's church at Fulda (fig. 138) was a T-shaped

basilica with a continuous transept. The particulars

of its design leave no doubt that it was modeled after the

Church of Old St. Peter's in Rome (fig. 141). Like that

church, its clerestory walls were supported by two rows of

columns which were surmounted not by arches, but by a

straight entablature; also like St. Peter's, the ends of the

transept arms were separated from the principal body of

the transept hall.

The ideological reasons for this emulation of the design

and size of the great Early Christian proto-basilica of Rome

during the reign of Emperor Charlemagne have been

brilliantly analyzed by Richard Krautheimer.[214]

The design

was an outgrowth of the general process of Romanization

of the Frankish Church and the Frankish kingdom that

started with the anointment of Pepin and his sons by Pope

Stephen II in 753 and culminated in the coronation of

Charlemagne as emperor on Christmas Eve of the year 800.

The ties of the Abbey of Fulda with Rome had been

especially strong. The missionary work of its founder, St.

Boniface (680-754), was closely linked to the papal see.

His successor, Abbot Sturmi (744-769), was an ardent

student of the customs of Monte Cassino on which the

customs of Fulda were based, and Fulda was the first

German abbey to be placed under the direct jurisdiction

of the Roman see.

[215]

There is no doubt that the return to the

design of the great western Roman basilicas of Constantine

the Great and of Pope Sylvester was an expression of the

renovation by Charlemagne of the universal Christian

empire inaugurated by Constantine the Great. One might

justly conclude that the propensity for colossal dimensions,

embodied in the abbey Churches of Fulda, Cologne, and

the Church of the Plan of St. Gall, was an integral part of

this ideology; but to explain the dimensional boldness of

these churches exclusively in such symbolic terms would

be a gross historical simplification. There are other more

functional and more specifically monastic reasons for the

appearance in transalpine Europe of churches of unprecedented

dimensions. One of them was the need to extend

the altar space in order to accommodate, in addition to the

officiating clergy, an entire community of monks celebrating

the divine services jointly in an elaborate ritual

involving chant and counter chant. Another reason was

the transfer of baptismal rites from a separate subsidiary

building to the basilica; in the Church of the Plan this

function claims one third of the entire nave. A third reason

was that the rapidly increasing veneration of saints resulted

in a multiplication of altars, each requiring additional space.

There also developed the desire to accommodate in a single

oratory a variety of cults that in earlier monastic churches

has been distributed over an entire family of buildings.

[216]

But the dimensional enlargement of the church that

these demands generated raised serious economic problems.

Whatever the historical and functional incentives may have

been for building churches of a magnitude of 300 feet and

more, there still remained the question of whether a community

of an average of 100 to 200 monks could afford to

build and maintain such structures. Ratger, the Abbot of

Fulda, thought so. But his monks, who paid for his

ambition with their toil and sweat, were disturbed by his

building program to the point of rebellion. In a formal

petition presented to Charlemagne in 812, they pleaded

that the construction of these "oversized and superfluous

buildings" (aedificia immensa atque superflua) be brought to

a halt or reduced to a normal pace, because it taxed the

brothers beyond endurance, left no time for the lectio

divina, and threatened to exhaust the monastery's economic

resources.[217]

The petitioners returned, defeated, to the

monastery: Charlemagne denied their petition. Hildebold,

then arch-chaplain and one of the emperor's closest

advisors, may have had a voice in the negative decision.

By 817, however, the climate had changed. Louis the

Pious was now emperor; sometime between 816 and 817

he received the same delegation with the same petition,

which this time was received favorably. As a direct result

of the petition, Ratger was deposed in favor of Eigil,

leader of the dissenting monks of Fulda. When Eigil was

installed as the new abbot in 817, he was admonished by

Louis "to stop this superfluous work of erecting structures

of inordinate size and to reduce the monastery's building

program to normal proportions."[218]

It appears that Louis

made use of the words the monks themselves had spoken,

the first time before Charlemagne and the second time

before him.

Overindulgence in costly building activities was not the

only reason for Ratger's fall, and by itself might not have

brought it about. He was also accused of violations of

sanctioned monastic customs,[219]

but the incident shows that

constructing a church 300 feet long was by no means an

easy matter for a monastic polity and could have disturbing

consequences not only for its economic stability but also

for its spiritual health.

The rebellion of the monks of Fulda against the building

activities of their abbot is the strongest historical evidence

to be offered in support of Boeckelmann's theory that the

explanatory title which stipulates a length of 200 feet for

the Church of the Plan is the expression of a programmatic

retrenchment.[220]

This measure might have been

directly related to the struggles of Fulda.