The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| I. 1. |

| I.1.1. |

| I.1.2. |

| I.1.3. |

| I.1.4. |

| I.1.5. |

| I.1.6. |

| I.1.7. |

| I. 2. |

| I.2.1. |

| I. 3. |

| I.3.1. |

| I.3.2. |

| I.3.3. |

| I. 4. |

| I.4.1. |

| I.4.2. |

| I. 5. |

| I.5.1. |

| I.5.2. |

| I.5.3. |

| I. 6. |

| I.6.1. |

| I. 7. |

| I.7.1. |

| I.7.2. |

| I.7.3. |

| I.7.4. |

| I. 8. |

| I. 9. |

| I.9.1. |

| I. 10. |

| I.10.1. |

| I.10.2. |

| I. 11. |

| I.11.1. |

| I.11.2. |

| I. 12. |

| I.12.1. |

| I.12.2. |

| I.12.3. |

| I.12.4. |

| I.12.5. |

| I.12.6. |

| I.12.7. |

| I. 13. |

| I.13.1. |

| I.13.2. |

| I.13.3. |

| I.13.4. |

| I.13.5. |

| I.13.6. |

| I.13.7. |

| I.13.8. |

| I. 14. |

| I.14.1. |

| I.14.2. |

| I.14.3. |

| I.14.4. |

| I.14.5. |

| I.14.6. |

| I.14.7. |

| I.14.8. |

| I.14.9. |

| I. 15. |

| I.15.1. |

| I. 16. |

| I. 17. |

| II. |

| II. 1. |

| II.1.1. |

| II.1.2. |

| II.1.3. |

| II.1.4. |

| II.1.5. |

| II.1.6. |

| II.1.7. |

| II.1.8. |

| II.1.9. |

| II.1.10. |

| II.1.11. |

| II.1.12. |

| II.1.13. |

| II. 2. |

| II.2.1. |

| II.2.2. |

HANS REINHARDT (1937 and 1952) |

| II. 3. |

| II.3.1. |

| II.3.2. |

| II.3.3. |

| II.3.4. |

| II.3.5. |

| II.3.6. |

| II.3.7. |

| II.3.8. |

| II.3.9. |

| II.3.10. |

| III. |

| III. 1. |

| III.1.1. |

| III.1.2. |

| III.1.3. |

| III.1.4. |

| III.1.5. |

| III.1.6. |

| III.1.7. |

| III.1.8. |

| III.1.9. |

| III.1.30. |

| III.1.11. |

| III. 2. |

| III.2.1. |

| III.2.2. |

| III.2.3. |

| III.2.4. |

| III.2.5. |

| III.2.6. |

| III.2.7. |

| III.2.8. |

| III. 3. |

| III.3.1. |

| III.3.2. |

| III.3.3. |

| III.3.4. |

| III.3.5. |

| IV. |

| IV. 1. |

| IV.1.1. |

| IV.1.2. |

| IV.1.3. |

| IV.1.4. |

| IV.1.5. |

| IV.1.6. |

| IV.1.7. |

| IV.1.8. |

| IV.1.9. |

| IV.1.10. |

| IV.1.11. |

| IV.1.12. |

| IV. 2. |

| IV.2.1. |

| IV.2.2. |

| IV.2.3. |

| IV. 3. |

| IV.3.1. |

| IV. 4. |

| IV.4.1. |

| IV.4.2. |

| IV. 5. |

| IV.5.1. |

| IV. 6. |

| IV.6.1. |

| IV. 7. |

| IV.7.1. |

| IV.7.2. |

| IV.7.3. |

| IV.7.4. |

| IV.7.5. |

| IV.7.6. |

| IV.7.7. |

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

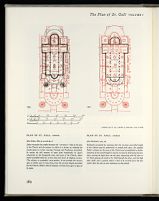

HANS REINHARDT (1937 and 1952)

Hans Reinhardt, who tends to under-evaluate the square

schematism of the Church of the Plan of St. Gall,[194]

attempted to resolve these discrepancies by developing a

drawing in which the Church was shown reduced to 200

feet. But to attain this goal he found himself compelled to

reduce the fore choir and the space of the crypt beneath it

to one-fourth of their original dimensions, and thus he

arrived at a modified plan which appears to retain no spiritual

kinship to the original concept of the drawing (fig.

131).[195]

Reinhardt contracts the Church most severely where

contraction hurts most: in the all-important area around

the high altar and the tomb of St. Gall, where the entire

body of the monks assembled daily for a total of four hours

or more, in common chant and the celebration of the divine

services. He placed the high altar against the very edge of

the raised choir, where it drops vertically down to the floor

level of the transept leaving no space for the officiating

priest and his attendants (fig. 132). A step on the eastern

side of the altar suggests that Reinhardt imagines the priest

to stand behind the altar facing west. This not only is

incompatible with what is known to have been a general

custom in Carolingian liturgy,[196]

but also in open conflict

with fourteen other altars in the Church of the Plan (figs.

84, 93 and 99). Their layout leaves no doubt that the

officiating priest stood west of the altar, facing east; the

128. SYRIA, BATUTA CHAPEL. PORCH, SOUTH SIDE

[courtesy Princeton University Archaeological Expedition to Syria]

leaves no doubt on this score.

One feels equally puzzled about Reinhardt's modification

of the crypt. The drafter of the Plan provided the

monastery with two crypts with different but complementary

functions. One is an outer corridor crypt in the

shape of a crank, which takes the pilgrims and the other

secular visitors to the tomb of St. Gall. The other is an

inner crypt which lies beneath the high altar and is reached

from the crossing through a passage marked accessus ad

confessionem, between the two flights of steps that lead up

to the fore choir (fig. 99). Being accessible from an area

130. PLAN OF ST. GALL. CHURCH

[after Dehio, 1887, pl. 42 and fig. 2]

Dehio reconciles the conflict between the "corrective" titles of the plan

of the Church and the manner in which it is drawn, by reducing the

arcade spans to 12 feet. Leaving Transept and Presbytery untouched,

he retains the full measure of space (and incidentally its square

schematism in the liturgically most vital part of the Church, where

monks assembled daily for no less than four hours of religious services.

This solution is acceptable—even perfect—if one excludes the western

apse, as Dehio seems to have done, from the 200-foot length prescribed

for the Church. Dehio's church measures 218 feet from apex to apex of

its apses.

131. PLAN OF ST. GALL. CHURCH

[after Reinhardt, 1952, 20]

Reinhardt proceeded by assuming that the 200-foot prescribed length

of the Church must be understood to include both apses. He adopted

Dehio's solution for the nave of the Church and accomplished a further

reduction of the overall length to exactly 200 feet by eliminating the fore

choir, moving the high altar into the apse, dispensing with the altar of

St. Paul, placing the tomb of St. Gall beneath the altar, and the high

altar itself, into a position where it had to be serviced from the east

rather than the west as was customary in this period.

129. SYRIA. BRAD CONVENT. PEDIMENT OF PORCH

[after Butler, 1929, 199, fig. 201]

Had Forsyth not discovered the 6th-century roof of St. Catherine's on Mt. Sinai, Brad and Batuta (fig. 128) would be sole evidence for

reconstructing the design of timbered roofs in Early Christian Syria. St. Catherine's roof is still functioning, in perfect condition. See The

Monastery of St. Catherine at Mt. Sinai, 1973.

have been a hall crypt providing the monks with prayer

space around the tomb of St. Gall.[197] Reinhardt eliminates

this confessio altogether and thus creates a spatial vacuum

in one of the most spiritually vital spots of the Church.

From a liturgical and functional point of view the

removal of the fore choir is fatal. Moreover, it is devastating

in its effect on the subsidiary spaces of the Sacristy and the

Scriptorium, which are built against the fore choir and, like

the latter, each cover a surface area of 40 × 40 feet. What

does Reinhardt propose to do with them? To reduce them

proportionately would render them unusable;[198]

to retain

them as originally planned would amount to an aesthetic

degradation of the apse which seems incompatible with its

liturgical and architectural function.

Reinhardt's proposal also seems unsuitable in general

historical terms. The interposition of a separate spatial unit

between apse and transept is one of the new and original

features of Carolingian architecture. It appeared in

Neustadt-on-the-Main shortly after 768-769 (figs. 116, 133);

in the abbey church of St. Riquier (Centula) between 790799

(fig. 135); in the church of Vreden around 800 (fig. 136);

in the cathedral of St. Mary and St. Peter of Cologne, prior

to the death of its founder, Archbishop Hildebold, d. 819

(fig. 139); in St. Mary at Mittelzell on Reichenau, as rebuilt

by Abbot Haito between 806 and 816 (fig. 134); and in the

abbey church of Hersfeld, if Groszmann's reconstruction is

correct, between 831 and 851.[199]

The primary motivation

for this new spatial entity was, as Thümmler has correctly

pointed out, the desire to isolate and strengthen the importance

of the high altar, at which the choral services were

held, and to provide more space for the officiating clergy.[200]

The increasing dimensions of the crypt, and the latter's

division into an outer corridor crypt for the pilgrims and an

inner confessionary for the monks, is directly related to this

development. Both of these innovations were responses to

pressing liturgical needs.

On altar orientation in Carolingian times, see Braun, I, 1924, 411ff.

and Otto Nussbaum's exhaustive study on The Position of the Officiating

Priest at the Christian Altar Prior to the Year 1000, which was not

published when these lines were written. Nussbaum's analysis of the

altarspace in Carolingian and Proto-Carolingian churches of Germany,

France and Switzerland has proven without any shadow of doubt that

from the end of the seventh century onward the officiating priest stood

between the altar and the populace facing the altar eastward. This is the

position in which he is shown on the ivory covers of the Drogo Sacramentary,

in scenes where he celebrates the Mass or is engaged in other

phases of the religious service. From a reading of the Frankish edition of

the Ordo Romanus I, issued during the first half of the eighth century (as

well as all later editions of this treatise) Nussbaum infers that when the

service was performed by the bishop in person, the latter had to walk from

his cathedra in the apex of the apse westward around and to the front of

the altar where he celebrated the Mass with his back turned toward the

worshipping crowd. (See Nussbaum, 1963, 305ff and summary of this

chapter, 358-66).

As correctly observed by Walter Boeckelmann, 1956, 127: "Sakristei,

Schreibstube und Bibliothek schrumpfen zu schmalen Kammern

zusammen . . . der korrigierte Plan kann nicht mehr als exemplarisch

gelten."

For Neustadt-on-Main, see Boeckelmann, 1951, 43-44 and 1956,

38ff and 58ff. For St. Riquier (Centula), see Gall, 1930 and E. Lehmann,

1938, 109. For Vreden see Winkelmann, 1953, 304-19. For the Carolingian

church of Cologne, see Weyres, 1965, 384-423; and the literature

quoted above on p. 26, note 4. For St. Mary in Mittelzell, see Reisser,

1960, and Christ, 1956. For Hersfeld, see Groszmann, 1955, 9, and

Feldkeller, 1964, 1-19.

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||