[ILLUSTRATION]

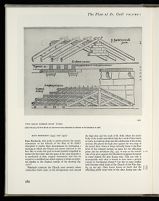

126. ROME. ROOF OF OLD ST. PETER'S RECORDED IN 1694 IN

CARLO FONTANA'S TEMPLUM VIATICANUM ET IPSIUS ORIGO. Detail of engraving same size as original

[after FONTANA, 1694, 99]

In publishing this design of what he refers to as "the trusses which sustained the

roof over the nave of Old St. Peter's" (LE INCAUALLATURE, CHE SOSTUEUANO LI

TETTI DELLA NAUE MAGGIORE . . . DEL ANTICA BASILICA VATICANA) Carlo Fontana

(1634-1714), disciple and collaborator of Lorenzo Bernini and architect in charge

of the Pontifical Office of Architects and Engineers, informs his readers that his

engraving was made after an "accurate drawing" (UN GIUSTO DISEGNO) tendered

him by an "informed person" (UNA PERSONA DILETTEUOLE); and that it was

because of the extraordinary constructional "sophistication" (INTELLIGENZA) as

well as the soundness of the timbers employed in these trusses that the roof of the

Constantinian basilica survived intact for so many centuries—to the extent that

when finally taken down, it was found to be in such good condition that its timbers

could be reassembled to sustain the roof of the Palazzo Farnese.

If timbers from the roof of Old St. Peter's were re-used in the Palazzo Farnese

(1546-1589) they must have come from the western half of the nave dismantled

by Bramante (1502) to make room for the construction of New St. Peter's. The

eastern half of the nave (closed off from the construction site by a provisional wall

under Paul III, 1534-1549) was demolished only in 1606 to make room for Carlo

Maderna's westward elongation of New St. Peter's. The roof timbers of this

portion were also re-used, this time for the Palazzo Borghese (1605-1621).

The names of the component members of the truss shown in Fontana's engraving

are enumerated on two scrolls which form part of the drawing. On these the tie

beams are referred to as CORDE MAGGIORI (B), the collar beams as CORDE

MINORI (C), the rafters as PARADOSSI (D), the center post suspended from the

apex of the truss as traue pendente adVso di monaco (E).

During the 12th to 13th centuries of its existence, the roof of the Constantinian

basilica of Old St. Peter's was, not surprisingly, in need of numerous repairs. A

complete account of them, including what in the sources is referred to as a "renovation"

by Pope Benedict XII (fecit fieri de novo tecta huius Basilicae sub anno

1341) is given by Michele Cerrati in Tiberii Alpharini, "De Basilica Vaticana

Antiquissima et Nova Structura" (STUDI E TESTI vol. 26 Rome, 1914, 13 note 2;

brought to my attention by my colleague Loren Partridge). There is no compelling

reason to presume that Benedict's renovation involved any basic changes in the

roof's design.

Fontana's rendering of the trusses of Old St. Peter's is in complete accord with

that which Vitruvius recommends for broad spans, except that all of the principal

members of the truss are doubled, and that the tie beams are fashioned in two

pieces, joined midway by an overlapping scarf joint. Owing to the extraordinary

width of the nave of Old St. Peter's (23.6 3m.), two-piece tie beams were necessary

since it would have been hard to find trees of sufficient height to yield single timbers

to span the whole space. Doubling all of the principal members was an extremely

wise constructional feature—probably the primary contribution to the longevity

of the Constantinian trusses—which evolved from the strategic function made of

the TRAVE PENDENTE. The scheme is a laminative one; a kind of truss-sandwich

is formed in which the structural components are assembled and joined in a function

that yields, in effect, a "pair" of trusses, but which is really a single homogeneous

creation of remarkable simplicity and purity of concept—revealing a mastery of static

mechanics that transcends Vitruvius and commands admiration today. Yet the design

does not seem to have found general acceptance. On the contrary, a medieval carpentry

truss, when it is impressive, gains our attention rather by its quaintness, its

intricacy of joinery and the complexity of its members.

The construction is ingenious. Transmitting the entire roof load to the two outer ends

of the tie beams, the principal rafters D-D are in compression and thus act as

columns as well as beams. Column action augmented by the deflection of beam

action is resisted by the horizontal strut C-C (collar beam) which functions in

compression. These minor chords support the rafter pairs midway in their span, a

construction that reduces the effective length of the rafters to approximately one-fourth

the nave span. Strut C-C is supported at mid-point by the vertical member

E-E (MONACO) which concurrently serves as a tension member to prevent sag in

the great lower chords. The scarf joint of these tie beams, tabled, locked, and

girdled by iron bands, prevents them from separating in the horizontal plane. In

contemplating the brilliance and simplicity of the design, remember that the wall-to-wall

span was above 84 feet—reflecting a state of theory of mechanics and

knowledge of structure existing in the 4th century!