CRYPT

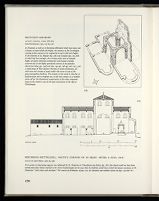

Crank-shaped corridor crypts consisting of two straight

longitudinal arms connected in the east by a straight transverse

arm, existed in St.-Germain of Auxerre (841-859;

fig. 157)[148]

and in St.-Pierre at Flavigny (864-878; fig.

158).[149]

In both these churches the space between the surrounding

arms of the corridor crypt was taken up by a

hall crypt. The earlier students of the Plan of St. Gall

overlooked the title which refers to an inner confessio

(accessus ad confessionem) and, misled by this oversight,

reconstructed the crypt incorrectly as a small rectangular

chamber beneath the high altar, accessible only from the

east by a short axial passage (Seesselberg, Dehio, Effmann,

and even Gall).

[150]

As a correction of this error, Ostendorf[151]

and Hecht[152]

offered two solutions: the former suggested a straight

passage extending from the middle of the transverse shaft

of the corridor crypt to the crossing (fig. 118); the latter, a

small hall crypt around the tomb of the Saint, accessible

both from east and west (fig. 119).

Hecht was on the right track, in my opinion, in suggesting

a hall crypt, but a hall crypt about 13 feet square is not

commensurate with the generous proportions of the other

parts of the Church. Had the designer intended a crypt

either of the type suggested by Ostendorf, or of that suggested

by Hecht, he could have expressed his intention

easily by the addition of only a few more lines. The fact

that he did not do this suggests that he had in mind a crypt

that extended over the entire width of the fore choir and as

far outward as the safety of its foundation walls permitted.

That groin-vaulted hall crypts of these dimensions were

fully within the technical competence of a Carolingian

architect may be inferred from the vaulted ground stories

of Carolingian westworks, a remarkable example of which

survives in the Abbey of Corvey (fig. 120).[153]

The excavations

of Joseph Vonderau at Fulda brought to light an

aisled hall crypt of approximately 30 × 30 feet, which was

built by Abbot Eigil between 820 and 822 under the east

choir of Ratger's church (802-817).[154]

It had nine groin

vaults resting on six freestanding piers or columns and nine

corresponding wall supports (fig. 122). The earliest

surviving hall-crypt of this type, as far as I know, is the

crypt of the Church of St. George in Oberzell on the island

of Reichenau (fig. 121), built by Abbot Haito III between

890 and 896 in an oratory that had been founded by

Bishop Haito (d. 823).[155]

By analogy with these parallels we have reconstructed

the confessio of the Church of the Plan of St. Gall as a hall

crypt having a surface area of 20 × 32½ feet, covered by 6

groin vaults, each 10½ feet square (fig. 123).[156]

The corridor

crypt may have been covered either by a simple barrel

vault, as in St.-Germain of Auxerre (fig. 157). or by a continuous

series of groin vaults, as in Flavigny (fig. 158).

Richard Krautheimer, in an exchange of letters devoted

to this subject, questioned the tenability of my interpretation

of the confessio of the Church of the Plan as an inner

hall crypt and, as we failed to arrive at any agreement on

this point, allowed me to discuss our variances of opinion

in print. Krautheimer feels convinced that the tomb of St.

Gall should be assumed to have had its place, not behind the

altar (as shown on the Plan) but beneath it. This was its

traditional place in Early Christian times from the fourth

century onward, as is exemplified by such churches as St.

Peter's, Santa Prassede, San Giorgio in Velabro, Santa

Cecilia, and many others.[157]

By analogy with these churches

Krautheimer suggests the entrance designated accessus ad

confessionem should not be interpreted as a gate giving

access to a hall crypt, but as a window fenestella opening into

a small rectangular chamber located in front or around

the tomb of the Saint.

Coming from a man whose knowledge about Early

Christian and Early Medieval Architecture is matched by

none, these views must be given the most careful consideration.

They are bound to be shared by others and have, in

fact, already been suggested by Hans Reinhardt in 1937

and 1952[158]

, by René Louis in 1952, and by Louis Hertig in

1958.[159]

In reviewing the evidence, I find that I cannot

concur with these interpretations for a number of reasons:

1. Nowhere in any of the forty-odd buildings of the

Plan or any of its other installations does the drafter of the

scheme show anything as lying behind another object when

he means it to lie beneath it. Wherever something was

meant to be below or above something else this is indicated

through an explanatory title beginning with the preposition

infra or supra.[160]

2. In the churches of the monastery of St. Gall, from

the seventh century onward, i.e., in the early Irish oratory

as well as the churches which superseded it under Abbot

Otmar (719-759) and Abbot Gozbert (830-836), the sarcophagus

which enshrined the body of the Saint was de facto

not below but behind the altar (inter aram et parietem). I

have already had occasion to refer to this fact.[161]

The same

condition prevailed at St. Riquier (Centula) as is attested

by a well-known passage in the Chronicle of Hariulf which

reads: "The tomb [of St. Richarius] itself, however, is so

placed that at the feet of this Saint his altar stands in an

elevated place, and at his head stands the altar of the

apostle St. Peter." (Sepultura vero ipsa ita posita est, ut a

parte pedum ipsius sancti altare sit in loco editiori, a parte

capitis sancti Petri Apostoli ara persistat.)[162]

3. To interpret accessus ("access") as fenestella ("window")

is doing injustice to the Latinity of the churchman

who framed the explanatory titles of the Plan. Accessus is

"bodily admittance" (accedere means "to approach," "to

step toward"). The concept fenestella implies the opposite,

because a window, although granting visual access, is part

of a wall or barrier that precludes a bodily approach. The

clarity of the other explanatory titles of the Plan suggests

that if the framer of these titles had wanted to designate the

presence of a window in the wall between the two flights of

stairs which lead from the crossing to the high altar he

would have done so by choosing the proper and traditional

term for this device.[163]

In Walahfrid Strabo's account of the

Miracles of St. Gall, there is mention of a fenestella opening

into the confessio of Abbot Gozbert's church at St. Gall,

but this window was in the pavement of the presbytery in

front of the high altar and it allowed the light of a lamp

suspended in front of that altar to "fall upon the altar of

the crypt beneath it.[164]

4. Finally, I must re-emphasize a point already amply

stressed in my descriptive analysis of the Plan: The layout

of the barriers in the two transept arms of the Church

leaves no doubt that the crank-shaped circumambient crypt

of the Church is reserved for the secular visitors of the

tomb, the southern arm serving as access for the Pilgrims

and Paupers, the northern arm for Distinguished Guests

(fig. 82).[165]

The monks, too, needed access to the sarcophagus

containing the relics of the Saint. I am drawing

attention once more in this context to chapter 7 of a

capitulary issued by Charlemagne in 789, which directs

in the clearest and most unequivocal terms that such

private oratories be constructed "near the place where the

sacred body rests so that the brothers can pray in secrecy."[166]

Monastic integrity and seclusion required that such an

oratory be separate from those spaces through which the

secular visitors gain access to the tomb. A simple fenestella,

located at a distance of 17½ feet from the westernmost end

of the tomb of St. Gall could not have performed this function

and, in fact would have been meaningless. There was

a need for devotional space in front of the tomb, sufficiently

large to accommodate an altar and large enough to admit

at least a modicum of worshipping monks. One might

quarrel about the relative size of that space, but one should

not question its existence.

In discussions of this as well as of many other important

features of the Plan of St. Gall, the innovative character of

this ingenious monastery scheme has been consistently

underrated. The spatial functional needs of a Carolingian

monastery church differed vastly from those of their

metropolitan Early Christian prototype churches and called

for new solutions. We shall have more to say about this in

the next chapter.