The Plan of St. Gall a study of the architecture & economy of & life in a paradigmatic Carolingian monastery |

| I. |

| I. |

| I. 1. |

| I.1.1. |

| I.1.2. |

| I.1.3. |

| I.1.4. |

| I.1.5. |

| I.1.6. |

| I.1.7. |

| I. 2. |

| I.2.1. |

| I. 3. |

| I.3.1. |

| I.3.2. |

| I.3.3. |

| I. 4. |

| I.4.1. |

| I.4.2. |

| I. 5. |

| I.5.1. |

| I.5.2. |

| I.5.3. |

| I. 6. |

| I.6.1. |

| I. 7. |

| I.7.1. |

| I.7.2. |

| I.7.3. |

| I.7.4. |

| I. 8. |

| I. 9. |

| I.9.1. |

| I. 10. |

| I.10.1. |

| I.10.2. |

| I. 11. |

| I.11.1. |

| I.11.2. |

| I. 12. |

| I.12.1. |

| I.12.2. |

| I.12.3. |

| I.12.4. |

| I.12.5. |

| I.12.6. |

| I.12.7. |

| I. 13. |

| I.13.1. |

| I.13.2. |

| I.13.3. |

| I.13.4. |

| I.13.5. |

| I.13.6. |

| I.13.7. |

| I.13.8. |

| I. 14. |

| I.14.1. |

| I.14.2. |

| I.14.3. |

| I.14.4. |

| I.14.5. |

| I.14.6. |

| I.14.7. |

| I.14.8. |

| I.14.9. |

| I. 15. |

| I.15.1. |

| I. 16. |

| I. 17. |

| II. |

| II. 1. |

| II.1.1. |

| II.1.2. |

| II.1.3. |

| II.1.4. |

| II.1.5. |

| II.1.6. |

| II.1.7. |

| II.1.8. |

| II.1.9. |

| II.1.10. |

| II.1.11. |

| II.1.12. |

| II.1.13. |

| II. 2. |

| II.2.1. | II.2.1 |

| II.2.2. |

| II. 3. |

| II.3.1. |

| II.3.2. |

| II.3.3. |

| II.3.4. |

| II.3.5. |

| II.3.6. |

| II.3.7. |

| II.3.8. |

| II.3.9. |

| II.3.10. |

| III. |

| III. 1. |

| III.1.1. |

| III.1.2. |

| III.1.3. |

| III.1.4. |

| III.1.5. |

| III.1.6. |

| III.1.7. |

| III.1.8. |

| III.1.9. |

| III.1.30. |

| III.1.11. |

| III. 2. |

| III.2.1. |

| III.2.2. |

| III.2.3. |

| III.2.4. |

| III.2.5. |

| III.2.6. |

| III.2.7. |

| III.2.8. |

| III. 3. |

| III.3.1. |

| III.3.2. |

| III.3.3. |

| III.3.4. |

| III.3.5. |

| IV. |

| IV. 1. |

| IV.1.1. |

| IV.1.2. |

| IV.1.3. |

| IV.1.4. |

| IV.1.5. |

| IV.1.6. |

| IV.1.7. |

| IV.1.8. |

| IV.1.9. |

| IV.1.10. |

| IV.1.11. |

| IV.1.12. |

| IV. 2. |

| IV.2.1. |

| IV.2.2. |

| IV.2.3. |

| IV. 3. |

| IV.3.1. |

| IV. 4. |

| IV.4.1. |

| IV.4.2. |

| IV. 5. |

| IV.5.1. |

| IV. 6. |

| IV.6.1. |

| IV. 7. |

| IV.7.1. |

| IV.7.2. |

| IV.7.3. |

| IV.7.4. |

| IV.7.5. |

| IV.7.6. |

| IV.7.7. |

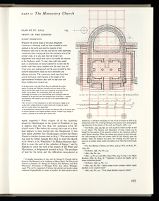

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||

II.2.1

THE CHURCH

AS DEFINED IN THE DRAWING

MATERIAL AND WALL THICKNESS

It is obvious that the Church of the Plan of St. Gall was

meant to be a masonry structure (figs. 107-113). Semicircular

apses, circular towers, spiral stairs, the columnar

order of the arcades of the nave—which, because of the way

they were spaced must have been surmounted by arches—

the barrel-vaulted corridors of the crypt, the arched galleries

of the abutting paradise—all these are features

germane to stone construction. Although there is abundant

evidence that in the ninth century a high percentage of the

smaller transalpine parish churches were built of timber,[129]

it is equally clear that an abbey church, intended to serve

as a model, could only have been constructed in stone. All

the major Carolingian churches were built in stone.

Some of the more hallowed parts of the Church, such as

the crypt or the interior of the apse and the fore choir, may

have been built in ashlar, but all the principal walls of the

Church were unquestionably built in roughly coursed

rubble. We have good parallels for both these techniques

in the Palace Chapel at Aachen (798-805), the Abbey

Church of Corvey-on-the-Weser (873-885), and the

Church of Germigny-des-Prés (799-818), in all of which

the external work was built in rubble, while most of the

structural parts of the interior were constructed in dressed

stones.[130]

Other examples of Carolingian ashlar construction

are found in the crypts of St.-Germain of Auxerre (841859)

and Flavigny (864-878).[131]

It is reasonable to assume that a church of the dimensions

of that of the Plan of St. Gall rested on foundations

about 5 feet wide. This is suggested by the dimensions of

the bases of the nave columns, and by the dimensions of

the supports which stand at the point where the aisle walls

meet the walls of the transept. It is equally reasonable to

assume that the full thickness of the foundation walls was

not retained in the walls themselves. A thickness of 3¼ feet

or 40 inches (one and one-half standard units) would

appear to be a reasonable assumption for both the aisle

walls and the clerestory walls.

For Aachen, see Buchkremer, 1947, and 1955, Schnitzler, 1950,

Boeckelmann, 1957 and Kreusch, 1966, 463-533; for Corvey-on-the-Weser,

see Effmann, 1929, Rave, 1957 and Busen, 1967; for Germigny-des-Prés,

Hubert, 1930, 534-68, Hubert, 1938, 76-77, and Collection

la nuit des temps, III, 1956, 55-59.

Extensive archaeological excavations have been conducted under

the pavement of the present cathedral of St. Gall in connection with the

installation of a new heating system for the church and other internal

renovations (Director: Dr. Hans-Rudolf Sennhauser, Zürich). As this

study goes into print a full report on the findings of this work is not

available (cf. II, 358-59). The reconstructions and hypotheses here

submitted will not be substantially affected by these excavations, whether

they tend to confirm or correct our views, since our objective is not the

analysis of the church which Abbot Gozbert built with the aid of the Plan,

but the reconstruction of the appearance of the church which is shown

on the Plan.

For St.-Germain of Auxerre, see Louis, 1952; for Flavigny, Bordet

and Galimard, 1906, Hubert, 1952, Nos. 85-87, and Lambert-Jouven,

1960.

ELEVATION

The elevation of the Church (figs. 108-113) must by necessity

remain a matter of conjecture. We have calculated it on

the assumption of certain minimal heights for consecutive

parts of the Church, moving in additive progression from

the lower to the upper portions of the building. The

aggregate of the estimates thus obtained produces a fairly

convincing picture.

The arcaded walls of the cloister, the northern wing of

which is built against the southern aisle of the Church,

must have been at least 10 feet high to give head clearance

to the monks who walked in this wing. The arched exits, in

the center of each cloister walk, are shown on the Plan

itself as being 7½ feet high. They must have had above

them a small amount of masonry to carry the timbers of the

roof which covered their walks. To this we have assigned a

height of 2½ feet.

The roof which covered the northern cloister walk—

assuming that it rose at an angle of about 30 degrees—

would have connected with the wall of the southern aisle

of the Church at a height of 17½ feet above the ground.

Beyond that point the aisle walls must have continued for

at least another 12½ feet in order to give clearance for the

windows (to which we have assigned an estimated height of

7½ feet). This would bring the top of the aisle walls to a

height of 30 feet. The aisle walls of the Abbey Church of

Fulda rose to a height of 8.75 m., which comes close to 30

Roman feet.[132]

The aisle walls of St. Gall cannot have been

any lower than that, since the tie-beams that supported the

aisle roofs had to clear the arches over the nave arcades.

These beams could not have cleared the arches at a level

lower than 30 feet, as will be shown presently.

The columns of the arcades of the nave are spaced at

intervals of 20 feet on center. The apex of the extrados of

the arches that rose from these columns cannot have been

any lower than 30 feet, without resulting in inordinately

depressed arcade proportions. Above the extrados of these

arches there must have been some 15 feet of clearance for

the aisle roof, and above the level of the aisle roof another

15 feet of clearance for the clerestory wall and its windows.

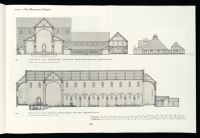

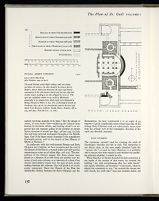

PLAN OF ST. GALL

108. CHURCH AND CLAUSTRUM, TRANSVERSE SECTION

The sections and elevations, as well as the perspective view of the

interior of the Church shown on the opposite and on subsequent

pages are our attempt to show what the Church of the Plan would

have looked like had it been built in full three-dimensional reality.

There is nothing mysterious about our conjecture. The nave of the

Church, as we are told by an unequivocal explanatory title, had a

width of 40 feet, each of its aisles a width of 20. We have assigned

to each component of the elevation of nave and Claustrum a

comfortable height required by its function and in this manner

arrived at a height of 30 feet for the aisle walls, and of 60 feet for

the nave walls. This is in full harmony with the decimal thinking

that controls the Plan in the planimetric sense, as our analysis of

its scale and construction has shown (above, pp. 77ff).

109. CHURCH, LONGITUDINAL SECTION

It is in longitudinal section that the pristine modular quality of the

proportions of the Church (cf. fig. 173) finds its strongest expression.

All measurements are related to the controlling module

of the crossing, a 40-foot square. The columnar interstices

(measured on centers) are exactly half that value. This condition

is responsible for the magnificent width and height of the

arcades—a concept fundamentally different from the low, narrow

intercolumniation of the great Early Christian prototype churches

from which the Church of the Plan is typologically derived (for

good examples see figs. 81, 141, 170, 174, and 177).

Although nave and transept were of equal width we cannot be

certain that they also were of equal height. Yet even if the transept

was lower, it is reasonable to assume that the crossing was

disengaged, i.e. framed by boundary arches on all four sides. There

are good contemporary parallels for either alternative (cf. fig. 15,

a low transept with boundary arches of unequal height; and figs.

116 and 117, high transepts with boundary arches of equal

height.)

110. PLAN OF ST. GALL. CHURCH INTERIOR. VIEW TOWARD EAST APSE

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

The Church of the Plan—its interior appearance here recreated by Ernest Born—was never built. Yet being conceived, it became a historical

reality, and our reconstruction for that reason, if correct in its principal lines, is a significant contribution to the visual history of medieval

architecture. The underlying compositional scheme (nave, two aisles and transept) is Early Christian. But none of the great metropolitan

basilicas of the West had arcades so wide and high, or proportions so rationally coordinated with a spatial master value, by the alignment of

the columnar interstices with the 40-foot module of the crossing square.

walls. The clerestory walls of the Abbey Church of

Fulda were 21.10 m. high, which corresponds roughly to

60 Roman feet.[133] The relation of the width to the heights

of the nave of the Church of the Plan would then be a ratio

of 1:1½ (40:60 feet), which is in harmony with the ratio of

1:1½ obtained in calculating the corresponding proportions

of the aisles (20:30 feet). From the floor to the ridge of its

highest roof, the Church of the Plan would probably have

measured 75 feet.

Admittedly these calculations are schematic, yet they are

based on constructional assumptions which are reasonable.

For Fulda, see von Bezold, 1936, 13, fig. 4; Beumann and Grossmann,

1949, 17-56; and Groszmann, 1962, 344-70.

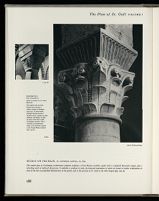

COLUMNS

The profiles of the bases, shafts, and capitals of the arcade

columns in our reconstruction (figs. 108-110) of the Church

of the Plan of St. Gall are based on the surviving Carolingian

columns of the church of St. Justin in Höchst-on-the-Main[134]

dating from shortly after 834 (fig. 114) and on

the surviving Carolingian columns of the Abbey Church of

Corvey (873-885).[135]

Had we known at the time our drawings

were made of the recently excavated capitals from the

church which Abbot Gozbert built in the monastery of St.

Gall with the aid of the Plan (fig. 115), we might have used

them as a model for the capitals of the Church of the Plan.

The height of the shaft of the columns at Höchst amounted

to about four times the height of its capitals, not counting

the imposts. In our reconstruction of the columns of the

Plan we have used about the same proportion. In Höchst

the relation of width to height of the arcade opening is

1:1.7; in the Church of the Plan, it is 1:1.5.

For St. Justinus in Höchst-on-the-Main, see Scriba, 1930, sketches

1, 2, and 3; Stiehl, 1931; Meyer-Barkhausen, 1929/30, 12 and 1933,

69-90.

CROSSING

The reconstruction of the crossing (figs. 108-112) has been

a matter of some controversy and, in fact, permits different

interpretations. Two basic questions present themselves

immediately: first, was the crossing surmounted by a

tower; and second, were the roofs of nave and transept of

equal height? The first of these two questions must, I

think, be answered in the negative. The second does not

admit a clear-cut answer.

Crossing towers have been assumed in Fiechter-Zollikofer's

and Gruber's reconstructions of the Church of

the Plan (figs. 277 and 282).[136]

Historically, this is a perfectly

feasible solution. Square towers, rising from crossings

produced by the interpenetration of two volumes of space

of essentially equal height, existed in the Abbey Church of

St.-Denis, constructed under Abbot Fulrad, 750-755;[137]

in the basilica of Neustadt-on-the-Main after 768/69[138]

(fig. 116); in the Abbey Church of St. Mary's on the island

of Reichenau, consecrated by Bishop Haito in 816[139]

(fig.

117); and in the church of St. Martin at Angers, end of

ninth century.[140]

But the Plan of St. Gall does not call for a

tower. In any of the other buildings, wherever a structure

was composed of two stories, the maker of the Plan indicated

this by an explanatory title, defining the function of

the lower story with a phrase that begins with the adverb

infra, "below," and that of the upper story by a phrase

that begins with the adverb supra, "above."[141]

Had he

meant the crossing to be surmounted by a tower, he could

have expressed his intention with a statement such as infra

chorus, supra turris—"below, the choir; above, a tower."

The fact that he did not do this suggests that a crossing

tower was not intended.

With regard to the respective heights of nave and transept,

the traditional view has been that they were of equal

height and that the crossing was framed by boundary

arches on all four sides, rising from wall pilasters and from

cruciform piers (figs. 107-110). It is in this manner that

the crossing unit was interpreted by Friedrich Seesselberg

(1897), Georg Dehio (1901), Wilhelm Effmann (1899 and

1912), Friedrich Ostendorf (1922), Joseph Hecht (1928),

Ernst Gall (1930), and Edgar Lehman (1938).[142]

It is also

the view that underlies the graphical reconstructions of the

Church, published by J. R. Rahn (1876), Joseph Hecht

(1928), H. Fiechter-Zollikofer (1936), and Karl Gruber

(1937 and 1952).[143]

However, this explanation of the Plan was questioned by

Hermann Beenken and by Samuel Guyer,[144]

who felt that

to interpret the supports in the corners of the crossing of

the Church as piers and pilasters was not permissible,

because the symbol used for these members (a square with

a circle inscribed) is identical with that which is used for

the nave columns. Beenken's and Guyer's criticism is based

on the arbitrary assumption that the square with the

inscribed circle could only have had the exclusive meaning

of "column." A more circumspect analysis of the use and

distribution of this symbol discredits this view. In the

Monks' Refectory, the House for Distinguished Guests,

and the Abbot's House, the same sign is used to designate

used to designate a lectern (analogiu). In the room for the

preparation of the holy bread and the holy oil it stands for

"oil press," in the Monks' Privy, for "a table with a

lantern" (lucerna), and in the hypocausts of the Monks'

Warming Room, the Novitiate and the Infirmary, it stands

for "chimney stack" (euaporatio fumi). It seems absurd to

persist on a course of reasoning which is based on the

supposition that the designer of the Plan of St. Gall was

unaware of the distinction between a pier and a column

because he used the same symbol for both of these structural

members. To do so would be no less incongruous than

to accuse him of having designed a clerestory wall whose

arcades rested on cupboards, lecterns, oil presses, lantern-carrying

tables, or chimney stacks.[145]

It is obvious that in drawing the structural members of

his church, the architect availed himself of a symbol whose

meaning was not limited to "columns," but could be understood

in the more general sense of "arch-support," leaving

it to the builder of the Church to interpret this sign as its

architectural context required, either as a freestanding

column (as in the nave arcades) or as an engaged half column

(wherever it is shown as being part of a wall), or as cruciform

piers (as in the four corners of the crossing). In order

to preclude any further misunderstandings I should like to

pursue more closely the evidence furnished by the Plan

itself.

The Plan indicates clearly that the supports which stand

in the western corners of the crossing must have been

shaped in such a way as to receive the arches of the easternmost

arcade on either side of the nave, as well as the arches

of the openings which connect the aisles with the transept.

Furthermore, they must have been able to receive on a

higher level the springing of the triumphal arch. The

existence of the triumphal arch cannot be proven on the

basis of the linear layout of the Plan, but its presence is

mandatory in a building of this size for obvious constructional

reasons.

The square symbols with the inscribed circles in the two

eastern corners of the crossing postulate the existence in

these places of engaged pilasters on columns, that make

sense only if we assume that they served as footing for

either a transverse arch, which separated the crossing from

the fore choir, or two longitudinal arches thrown across the

transept arms in prolongation of the nave walls. One of these

two assumptions is obligatory, but the fact that only one

of them can be established compellingly does not preclude

the other. The Plan does not provide us with any evidence

that would warrant dismissing the possibility that the

Church was meant to have had an arch-framed crossing

(fig. 110).

As for the elevation of this crossing unit of the Church of

the Plan, it is futile to speculate whether it belonged to the

fully developed type with arches of equal height, which

became a standard feature of western architecture at the

period of the Romanesque, or whether it belonged to any

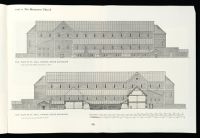

PLAN OF ST. GALL

111.A CHURCH. NORTH ELEVATION

111.B CHURCH. SOUTH ELEVATION

Because of the surrounding buildings, no one standing on the

monastery grounds would have been able to entirely encompass

these two magnificent views of the Church. They strikingly

portray the antinomy and balance between directional thrust and

inward-turning that characterizes Carolingian double-apsed

churches of this type.

One may feel perplexed by the aesthetic kinship of these two-apsed

Carolingian churches—not so much by such unidirectional classics

of Early Christian architecture as Old St. Peter's (fig. 141) or

St. Paul's Outside the Walls (fig. 81) upon which their layout is

based (cf. below, p. 187ff); but rather with the pagan imperial

prototypes of these great palaeochristian transept churches, the

Roman market halls, many of which had apses at each end; and

most of which had attached to one broad side (as in the case of the

Church of the Plan of St. Gall) an open, galleried court through

which the building was entered laterally rather than on axis

(basilica of Trajan, fig. 239; Severan basilica at Lepcis Magna,

fig. 159; basilica of Silchester, fig. 202).

The Church of the Plan of St. Gall is a sophisticated combination

of both concepts. It is directional like the churches of the two

prime apostles, because the transept and presbytery, in the

heaping-up of their spatial masses, make it clear that the architecturally

most prominent part of the church, and its liturgical

focus, is its cruciform eastern end. This effect is emphasized in the

interior, through the raising of the floor level of the Presbytery

over the level of all of the other parts of the church; and on the

exterior, through the attachment to the two transept arms, on

either side of the Presbytery, of two double storied lean-to's, one

containing Sacristy and Vestry (south side) the other Scriptorium

and Library (north side).

Yet this directionalism has no starting point, because the church

has no façade. Instead it faces the outside world with a counter

apse which binds its spatial energies inward, blocking access to the

nave, and channeling visiting laymen in a semicircular movement

around it to aesthetically insignificant secondary entrances in the

aisles (cf. caption to fig. 82).

Double apsed-churches (cf. below, pp. 199ff) were common in the

palaeochristian architecture of North Africa, but rare in the

Italian homeland. Recent studies have shown that they also were

very common in Visigothic Spain (for a brief review see the

article Hispania in Reallexikon zur Byzantinischen

Kunst) which may have played a more important role in transmission

of this motif to the Carolingian world than has hitherto

been admitted or recognized.

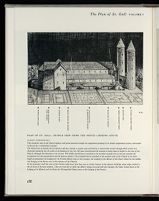

112. PLAN OF ST. GALL. CHURCH SEEN FROM THE NORTH LOOKING SOUTH

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

This broadside view of the Church displays with great pictorial strength the magnificent grouping of its slender longitudinal masses, intercepted

in the east by a monumental transept.

The Church has no façade, but its entrance side has, instead, a counter apse encircled by a semicircular atrium through which visitors are

channeled sidewards into the aisles of the building (cf. fig. 82). We have reconstructed the transept as being equal in height to the nave of the

Church, although this dimension is not certain. The double-storied lean-to attached to the northern transept arm in the east contains the

Scriptorium (on the ground floor) and the Library (above). The extended lean-to attached to the northern aisle of the Church in its entire

length accommodates the Lodging for the Visiting Monks (next to the transept), the Lodging of the Master of the Outer School (in the middle,

and Lodging of the Porter next to the entrance of the Church).

In the monastery itself this view of the Church could never have been seen in totality because of the adjacent buildings whose ridge reached to

the sill level of the nave windows. They are from left to right: the Abbot's House (co-axial with the transept), the Outer School (next to the

Lodging of its Master) and the House for Distinguished Guests (next to the Lodging of the Porter).

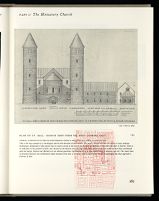

113. PLAN OF ST. GALL. CHURCH SEEN FROM THE WEST LOOKING EAST

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION [after the model displayed at Aachen in 1965]. ELEVATION TAKEN ON SECTION X-X

This is the only example of a Carolingian church with detached circular towers. The motif is unique and does not appear in later medieval

architecture. Explanatory titles denote that its towers carried at the top of one the altar of Michael, of the other, the altar of Gabriel. There is

no indication of the presence of bells, and, because of the distance from the high altar, their sound in any case could not have been coordinated

with the liturgy. Gabriel and Michael are the celestial guardians representing forces of light against those of darkness and evil. The towers have

no practical function, but symbolically might announce from afar to travellers (and at close range almost threateningly) that they approach a

Fortress of God.

115.X REICHENAU-MITTELZELL

HAITO'S CHURCH OF ST. MARY

(806-816)

This capital from the main

arcades was re-used in a

column ascribed to Witigowo

(985-997). Its floral motifs,

although distantly based on

classical sources, represent in their

simplicity and flatness of relief

an early, rather than a high

Carolingian tradition. One is

reminded of developmental

stages of the Godescale Gospels

or the Genoels-Elderen diptych

(Fig. 190.X).

114. HÖCHST-ON-THE-MAIN. ST. JUSTINIUS, CAPITAL, CA. 834

This superb piece of Carolingian architectural sculpture combines a Greco-Roman acanthus capital with a strigilated Byzantine impost, plus a

refreshing touch of medieval abstraction. It embodies a synthesis of style, the historical ingredients of which are found in similar combinations in

some of the most accomplished illuminations of the period, such as the portrait of St. Luke in the Ada Gospels (fig. 184.A)

115 ST. GALL CAPITAL.

EXCAVATED BELOW THE PAVEMENT OF THE PRESENT CHURCH

CAPITAL FROM GOZBERT'S ABBEY CHURCH (830-837)

[after Sennhauser, "Zu den Ausgrabungen in der Kathedrale, der ehemaligen

Klosterkirche von St. Gallen," Festschrift zum 70. Geburtstag von Architekt

Hans Burkard, Gossau 1965, 109-116.]

More classicizing in the detail of its design than the capital of Höchst,

opposite, this one nevertheless seems to project a touch of weariness with

the classical tradition, clearly lacking stylistic firmness and sophistication

of the Höchst capital.

The capital, presumably from the columnar order of the nave arcades of

Gozbert's church, was re-used in the masonry of the foundations of the

Gothic choir built by abbots Eglolf and Ulrich VIII, between 1439 and

1483 (II, p. 326). It was discovered by R. H. Sennhauser in 1964 when

the south wall of the choir was breached to accommodate a modern

heating duct. For other discoveries made during these operations, see

preliminary report on Sennhauser's findings (II, 358-59).

Figure 115 shown above is reproduced from an original drawing executed in carbon

pencil, size, 8.5 × 10 inches (215 × 25.5cm). The drawing is based on a document

not adequate for direct photographic reproduction but possessing legibility features

of sufficient clarity and definition of form and detail to permit a drawing to be

developed with reasonable fidelity to the original artifact and satisfactory for the

purpose here.

term "abgeschnürte Vierung."[146] It is true that a great

many Carolingian churches had low transepts, but it is

equally true that high transepts with arch-framed crossing

units existed in St.-Denis, as early as 750-755; in Neustadt-on-the-Main,

shortly after 768/69 (fig. 116); in the Abbey

Church of St. Mary's in Reichenau, before 816 (fig. 117).

The low transept may have been more common, but a

square crossing produced by the interpenetration of two

volumes of space of equal height, and framed by arches on

all four sides, was entirely within the realm of possible

solutions open to a Carolingian architect. Advanced and

superior as he was in so many other respects, the designer

of the Church of the Plan of St. Gall may also, in this

instance, have anticipated a development which had as yet

not found a widespread application in Carolingian architecture.

In our reconstruction of the Church of the Plan (figs.

108-112) we have chosen to emphasize this possibility. Had

we had more leisure and space, we would have supplemented

this solution with an alternate drawing that showed the

Church with a low transept. A reconstruction in which the

Church is furnished with a low transept will be found in

Emil Reisser's study of the Abbey of St. Mary's in

Reichenau-Mittelzell.[147]

The tower of St.-Denis is mentioned in the Miracula Sancti Dyonisi,

I, xv; see Mabillon, Acta, III:2, 348; see also Crosby, 1953, 12-18, and

53, fig. 14.

For Neustadt-on-the-Main, see Boeckelmann, 1951, 43-45; and

idem, 1952, 109; idem, 1956, 58-62.

For St. Mary's at Reichenau, see Reisser, 1933, 163ff; and idem,

1935, 210ff; also Boeckelmann, 1952, 108.

This is the procedure chosen in the case of the Dormitory, the

Refectory, the Cellar, the Abbot's House, and the Stable for Horses and

Oxen; see below, figs. 208, 211, 225, 251; and II, fig. 474.

Seesselberg, 1897, 99, fig. 279; Dehio and von Bezold, I, 1901,

161-62 and Plates, I, pl. 42, fig. 2; Effman, 1899, 163, fig. 134, and 1912,

11, fig. 29; Ostendorf, 1922, 43, fig. 53; Hecht, I, 1928, pl. 4; Gall, 1930,

pl. 1; E. Lehman, 1938, 17, note 2.

Beenken, loc. cit., the discussion of the arch-framed crossing, in

Carolingian architecture suffers somewhat from a skeptical over-reaction

to Effmann's self-assurance in proposing a fully developed arch-framed

crossing in his reconstructions of Centula and Corvey. As far as Centula

is concerned, the situation is not very different from St. Gall. Beenken

could not disprove Effmann's assumption of an arch-framed crossing;

he could only point out that the crossing of Centula need not necessarily

have belonged to the fully developed type suggested by Effmann. On the

problem of the "abgeschnürte Vierung," cf. also Boeckelmann, 1954, 10113;

and Grodecki, 1958, 45ff.

Reisser, 1960, 80ff and figs. 326 and 327. Reisser's reconstruction

of the Church of the Plan (which was made before the publication of the

color facsimile of the Plan in 1952 but published posthumously in 1960)

has two anomalies which I fail to understand. Reisser reduces the arcades

of the nave from 9 to 8; and he omits the transverse arm of the crank-shaped

corridor crypt.

CRYPT

Crank-shaped corridor crypts consisting of two straight

longitudinal arms connected in the east by a straight transverse

arm, existed in St.-Germain of Auxerre (841-859;

fig. 157)[148]

and in St.-Pierre at Flavigny (864-878; fig.

158).[149]

In both these churches the space between the surrounding

arms of the corridor crypt was taken up by a

hall crypt. The earlier students of the Plan of St. Gall

overlooked the title which refers to an inner confessio

(accessus ad confessionem) and, misled by this oversight,

reconstructed the crypt incorrectly as a small rectangular

chamber beneath the high altar, accessible only from the

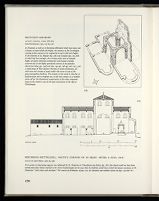

116. NEUSTADT-AM-MAIN

SAVIOR'S CHURCH, AFTER 768-769

[after Boeckelmann, 1954, 105, fig. 41a]

In Neustadt, as well as in Reichenau-Mittelzell which had naves and

transepts of equal width and height, the masonry of the Carolingian

crossing arches survives in its original form and to full arch height.

In the churches of St. Riquier (fig. 196) and Cologne (fig. 15), both

of which had low transepts, the crossing arches were of unequal

height. In Early Christian architecture arch-framed crossings

occurred only in the highly specialized context of the quincunx

church (see below, pp. 190ff and figs. 145-46, 148-49, and 152), and

a small group of Near Eastern churches of minute dimensions, all

with nave and transept of equal width—but never in any of the

great metropolitan basilicas. The transfer of this motif to churches of

basilican plan and its incipient use, in this new context, as a modular

prime cell for the dimensional organization of the other component

spaces of the church is one of the great innovations of the Age of

Charlemagne.

117. REICHENAU-MITTELZELL. HAITO'S CHURCH OF SS MARY, PETER & PAUL (816)

ELEVATION [after Reisser, 1960, fig. 296]

If its system of alternating supports was influenced by St. Demetrios in Thessalonica (see below, fig. 188), this church could not have been

started until after Haito returned in 811 from Constantinople (on his way there he doubtless would have visited the famous sanctuary of St.

Demetrios) "with artists and workmen." For sources see Erdmann, 1974a, 501; for elevation and modular system see figs. 134 and 171.

and even Gall).[150]

As a correction of this error, Ostendorf[151]

and Hecht[152]

offered two solutions: the former suggested a straight

passage extending from the middle of the transverse shaft

of the corridor crypt to the crossing (fig. 118); the latter, a

small hall crypt around the tomb of the Saint, accessible

both from east and west (fig. 119).

Hecht was on the right track, in my opinion, in suggesting

a hall crypt, but a hall crypt about 13 feet square is not

commensurate with the generous proportions of the other

parts of the Church. Had the designer intended a crypt

either of the type suggested by Ostendorf, or of that suggested

by Hecht, he could have expressed his intention

easily by the addition of only a few more lines. The fact

that he did not do this suggests that he had in mind a crypt

that extended over the entire width of the fore choir and as

far outward as the safety of its foundation walls permitted.

That groin-vaulted hall crypts of these dimensions were

fully within the technical competence of a Carolingian

architect may be inferred from the vaulted ground stories

of Carolingian westworks, a remarkable example of which

survives in the Abbey of Corvey (fig. 120).[153]

The excavations

of Joseph Vonderau at Fulda brought to light an

aisled hall crypt of approximately 30 × 30 feet, which was

built by Abbot Eigil between 820 and 822 under the east

choir of Ratger's church (802-817).[154]

It had nine groin

vaults resting on six freestanding piers or columns and nine

corresponding wall supports (fig. 122). The earliest

surviving hall-crypt of this type, as far as I know, is the

crypt of the Church of St. George in Oberzell on the island

of Reichenau (fig. 121), built by Abbot Haito III between

890 and 896 in an oratory that had been founded by

Bishop Haito (d. 823).[155]

By analogy with these parallels we have reconstructed

the confessio of the Church of the Plan of St. Gall as a hall

crypt having a surface area of 20 × 32½ feet, covered by 6

groin vaults, each 10½ feet square (fig. 123).[156]

The corridor

crypt may have been covered either by a simple barrel

vault, as in St.-Germain of Auxerre (fig. 157). or by a continuous

series of groin vaults, as in Flavigny (fig. 158).

Richard Krautheimer, in an exchange of letters devoted

to this subject, questioned the tenability of my interpretation

of the confessio of the Church of the Plan as an inner

hall crypt and, as we failed to arrive at any agreement on

this point, allowed me to discuss our variances of opinion

in print. Krautheimer feels convinced that the tomb of St.

Gall should be assumed to have had its place, not behind the

altar (as shown on the Plan) but beneath it. This was its

traditional place in Early Christian times from the fourth

century onward, as is exemplified by such churches as St.

Peter's, Santa Prassede, San Giorgio in Velabro, Santa

Cecilia, and many others.[157]

By analogy with these churches

Krautheimer suggests the entrance designated accessus ad

confessionem should not be interpreted as a gate giving

access to a hall crypt, but as a window fenestella opening into

a small rectangular chamber located in front or around

the tomb of the Saint.

Coming from a man whose knowledge about Early

Christian and Early Medieval Architecture is matched by

none, these views must be given the most careful consideration.

They are bound to be shared by others and have, in

fact, already been suggested by Hans Reinhardt in 1937

and 1952[158]

, by René Louis in 1952, and by Louis Hertig in

1958.[159]

In reviewing the evidence, I find that I cannot

concur with these interpretations for a number of reasons:

1. Nowhere in any of the forty-odd buildings of the

Plan or any of its other installations does the drafter of the

scheme show anything as lying behind another object when

he means it to lie beneath it. Wherever something was

meant to be below or above something else this is indicated

through an explanatory title beginning with the preposition

infra or supra.[160]

2. In the churches of the monastery of St. Gall, from

the seventh century onward, i.e., in the early Irish oratory

as well as the churches which superseded it under Abbot

Otmar (719-759) and Abbot Gozbert (830-836), the sarcophagus

which enshrined the body of the Saint was de facto

not below but behind the altar (inter aram et parietem). I

have already had occasion to refer to this fact.[161]

The same

condition prevailed at St. Riquier (Centula) as is attested

by a well-known passage in the Chronicle of Hariulf which

reads: "The tomb [of St. Richarius] itself, however, is so

placed that at the feet of this Saint his altar stands in an

elevated place, and at his head stands the altar of the

apostle St. Peter." (Sepultura vero ipsa ita posita est, ut a

parte pedum ipsius sancti altare sit in loco editiori, a parte

capitis sancti Petri Apostoli ara persistat.)[162]

118. PLAN OF ST. GALL

Crypt of Church, Ostendorf's interpretation

[Ostendorf 1922, 43, fig. 279]

This proposal provides a shaft too narrow to

allow monks to pray in privacy near the

saint's tomb, and furnishes insufficient

separation from laymen,

119. PLAN OF ST. GALL

Crypt of Church, Hecht's interpretation

[Hecht, 1928, pl. 10b]

Hecht is more generous in his provision of

space around the tomb of St. Gall than is

Ostendorf, yet he still allows for too

indiscriminate an intermixture of monks and

laymen.

120. CORVEY-ON-THE-WESER, GERMANY

WESTWORK OF ABBEY CHURCH, GROUND FLOOR (873-885)

While most Early Christian and Carolingian churches were timber roofed, the art of vaulting

continued to be practised in crypts and westworks, where it was needed to carry the weight of the

superincumbent work. Corvey and St. Riquier are magnificent examples of this tradition.

In the 11th century the groin was freed from confinement underground or in the avant-corps and

ascended into the principal body of the church, first to aisles (Jumièges, figs. 189.A-D), then to

nave (Speyer, figs. 190.A-B). In the transfer of Carolingian modularity to the elevation of the

church, and its marriage, at roof level, with the tradition of groin vaulting, medieval bay

division enters its final and most accomplished phase.

3. To interpret accessus ("access") as fenestella ("window")

is doing injustice to the Latinity of the churchman

who framed the explanatory titles of the Plan. Accessus is

"bodily admittance" (accedere means "to approach," "to

step toward"). The concept fenestella implies the opposite,

because a window, although granting visual access, is part

of a wall or barrier that precludes a bodily approach. The

clarity of the other explanatory titles of the Plan suggests

that if the framer of these titles had wanted to designate the

presence of a window in the wall between the two flights of

stairs which lead from the crossing to the high altar he

would have done so by choosing the proper and traditional

term for this device.[163]

In Walahfrid Strabo's account of the

Miracles of St. Gall, there is mention of a fenestella opening

into the confessio of Abbot Gozbert's church at St. Gall,

but this window was in the pavement of the presbytery in

front of the high altar and it allowed the light of a lamp

suspended in front of that altar to "fall upon the altar of

the crypt beneath it.[164]

4. Finally, I must re-emphasize a point already amply

stressed in my descriptive analysis of the Plan: The layout

of the barriers in the two transept arms of the Church

leaves no doubt that the crank-shaped circumambient crypt

of the Church is reserved for the secular visitors of the

tomb, the southern arm serving as access for the Pilgrims

and Paupers, the northern arm for Distinguished Guests

(fig. 82).[165]

The monks, too, needed access to the sarcophagus

containing the relics of the Saint. I am drawing

attention once more in this context to chapter 7 of a

capitulary issued by Charlemagne in 789, which directs

in the clearest and most unequivocal terms that such

private oratories be constructed "near the place where the

sacred body rests so that the brothers can pray in secrecy."[166]

Monastic integrity and seclusion required that such an

oratory be separate from those spaces through which the

secular visitors gain access to the tomb. A simple fenestella,

located at a distance of 17½ feet from the westernmost end

of the tomb of St. Gall could not have performed this function

and, in fact would have been meaningless. There was

a need for devotional space in front of the tomb, sufficiently

large to accommodate an altar and large enough to admit

at least a modicum of worshipping monks. One might

quarrel about the relative size of that space, but one should

not question its existence.

In discussions of this as well as of many other important

features of the Plan of St. Gall, the innovative character of

this ingenious monastery scheme has been consistently

underrated. The spatial functional needs of a Carolingian

monastery church differed vastly from those of their

metropolitan Early Christian prototype churches and called

for new solutions. We shall have more to say about this in

the next chapter.

Seesselberg, 1897, 99, fig. 279; Dehio and von Bezold, Plates I, pl.

42, fig. 2; Effmann, 1899, 163, fig. 134, and 1912, 11, fig. 20; Gall, 1930,

pl. 1.

These reconstructions were first displayed in the Council of Europe

Exhibition "Karl der Grosse" held in Aachen in 1965, in connection with

the showing of a model reconstruction of the buildings shown on the

Plan of St. Gall (cf. above, p. 6). They were first published in Horn

1966, plate figures 8 and 9.

For St. Peter's see Toynbee and Ward Perkins, 1956, 136ff (also

below, pp. 196ff). For S. Prassede, S. Giorgio in Velabro, Santa Cecilia

and others see Braun, I, 1924, 558.

Reinhardt, 1937, 237 and 1952, 18 and figs. on 21 and 22 (also above,

p. 141, and below, pp. 180ff).

With regard to the use of the term fenestella for windows opening

into a chamber sheltering the relics of a saint, see Braun, I, 1924, 561ff.

WINDOWS

The reconstruction of the windows offers no serious difficulties,

as Carolingian windows survive in many places.

We have fashioned the windows of the Church of the Plan

after those of the basilica of Einhardt at Steinbach-in-the

Odenwald (827), the design of which has been the subject

of a special study by Walter Boeckelmann.[167]

These

windows are narrow at the outer wall surface; however, the

jambs are strongly splayed toward the inside, with steeply

slanting sills and arches. Splayed windows appear sporadically

in Roman architecture,[168]

and toward the end of the

sixth century (although not a typical feature even then), and

they were apparently common enough to attract the notice

of Gregory the Great (590-604), who expressed himself on

their virtues:

In splayed windows that portion through which the light enters is

narrow but the inner jambs which receive the light are wide. In like

manner, the minds of those who contemplate, although they perceive

the true light only weakly, are broadened internally to ample

fullness. . . . And as the windows are both open and protected, so

the hearts of those who are receptive to the grace of God will be

replenished, and yet will not permit the enemy to enter in haughtiness.[169]

In times when glass was a rare and costly commodity, the

splayed window offered the advantage of keeping the area

of glass minimal, while admitting the maximum amount of

light.

Sancti Gregorii Magni Homiliarum in Ezechielem, Lib. II, Hom. 5,

chap. 17 (Migne, Patr. Lat., LXXVI, 1849, col. 995):

In fenestris obliquis pars illa per quam lumen intrat angusta est, sed pars

interior quae lumen suscipit lata, quia mentes contemplantium quamvis

aliquid tenuiter de vero lumine videant, in semetipsis tamen magna amplitudine

dilatantur . . . Et patent itaque fenestrae, et munitae sunt, quia et

aperta est in mentibus eorum gratia qua replenitur, et tamen ad se adversarium

ingredi per superbiam non permittunt.

Isidore of Seville (c. 570-636), too, makes mention of splayed windows

and remarks that in his days these were often seen in buildings used for

the storage of grain: Fenestrae sunt quibus pars exterior angusta et interior

diffusa [est] quales in horreis videmus. (Isidori Hisp. Episc. Etymol. sive

Orig., Book XV, chap. 7, 5; ed. Lindsay, 1911, written between 622 and

633).

ROOF

There can be no doubt that the frame of the roof of the

Church of St. Gall was meant to be constructed in timber.

It took two more centuries in the development of western

architecture before basilicas of major dimensions were

vaulted in stone. Since no timbered Carolingian church

roofs survive to guide us in our reconstruction, the details

of the carpentry of the roof of the Church must remain a

matter of conjecture. The earliest extant medieval church

roofs date from the twelfth century. They consist of simple

sequences of coupled rafters of uniform scantling rising

121. REICHENAU-OBERZELL. CHURCH OF ST. GEORGE (890-896). CRYPT

This view shows the crypt as seen from its entry shaft. Of monumental simplicity and great structural beauty, the crypt is square in plan and coextensive

with the square choir rising above it. It is covered by nine groin vaults supported in the center by four free-standing columns.

and an elaborate system of bracing struts. The cross section

of the twelfth-century roofs of the churches of St.-Germain-des-Prés

and St.-Pierre-de-Montmartre in Paris (figs. 124125)

are typical examples.[170]

Although perfectly feasible for churches of moderate

dimensions, this roof design would not have been solid

enough, in my opinion, to safely span the vast interstices

between the clerestory walls of the larger Carolingian

churches. The nave of the Abbey Church of Fulda, 802819

(fig. 138) had an inner width of 17m (calculated by

Vonderau as corresponding to 60 Roman feet),[171]

and thus

was narrower than the nave of its Early Christian prototype,

Old St. Peter's in Rome (fig. 141), by only a small margin

(18.80m, listed by Volbach as corresponding to 61 feet,

8 inches).[172]

I am inclined to believe that the roof that

covered the basilica of Fulda derived its design from the

same source that inspired the entire building.[173]

That the

roof of Old St. Peter's was well known to Frankish architects

may be inferred from two letters of Pope Hadrian I to

Charlemagne (one written between 779 and 801; the other,

between 781 and 786), in which the pontiff asks the

emperor not only for the beams for the repair of the roof

of St. Peter's but also for a magister to supervise the work—

clear evidence of the high esteem Frankish carpenters and

builders enjoyed in Rome in those days. The Pope asked

for the services of no lesser man than Wilcharius, Bishop of

Sens, to direct the restoration.[174]

Carlo Fontana made an engraving in 1694 of the roof

trusses spanning the nave of Old St. Peter's (fig. 126); these

he considered to be an authentic record of the original

(Early Christian) roof of the church.[175]

The nave span of the

Church of the Plan is only about one-half (40 feet) of that

of Old St. Peter's, and therefore, would not have required a

roof of such heavy design. In our reconstruction of the roof

of the Church (figs. 108-110) we have been guided by a roof

design which, it is believed, was a standard Early Christian

type, and which, to judge by a description in Vitruvius'

Fourth Book,[176]

must also have been standard for broad

spans in Roman Imperial times. Vitruvius distinguishes

between two roof types, one suited for "spaces of relatively

small dimensions" (commoda spatia), the other for buildings

involving "broader spans" (majora spatia). The former,

according to his description, consisted of two simple

rows of rafters converging at the top in a ridge beam and

extending downward all the way out to the eaves of the

building (columen et cantherii prominentes ad extremam

subgrundationem); the latter was made up of a sequence of

vertical trusses which supported the covering of the roof

by means of purlins. Vitruvius lists the different parts that

make up this frame and tells us that their names express

their different functions (ea autem uti in nominationibus ita

in re habet utilitates); "Under the roof, if the span is

broader, there are tie-beams (transtra) and bracing struts

(capreoli). . . . Above the principal rafters (cantherii) there

are the common rafters (asseres) extending outward sufficiently

to protect the walls with their overhang."[177]

This terminology is indeed highly descriptive and typical

of the classical habit of defining the functions of inanimate

objects by imagery borrowed from animate life. Cantherius

(a beast of burden) is an appropriate term for the load-bearing

action of the rafters; capreolus (a wild goat) expresses

vivdly the butting action of the diagonal timbers

locked in the center and at the bottom of the king post like

the horns of two fighting goats; transtrum, derived from the

preposition trans (across) is equally expressive of the purpose

of the large crossbeam that forms the base of the truss.

Vitruvius fails to furnish us with the name for the king

post, which in this type of construction rises almost

invariably from the center of the tie-beam to the ridge pole.

The primary function of this post is not to support, as has

been frequently thought, but to serve as a base of departure

for the diagonal bracing struts which prop the rafters midway

in their span, and thus prevent them from sagging

inward under the load of the roof covering.[178]

The early

translators and commentators on Vitruvius have interpreted

these descriptions of the two basic Roman roof

types correctly; and such reconstructions based upon these

interpretations as are found, for instance, in Barbaro's

Italian translation of Vitruvius, published by Francesco

Marcolini in 1556 (fig. 127)[179]

or in the 1827 edition of

Vitruvius published with commentary by Joannes Polenus,[180]

cannot, in my opinion, be improved upon.

The correctness of such interpretations has recently been

confirmed by George H. Forsyth's extraordinary discovery

of the original timbers of the roof of the sixth-century

church of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai, which is the

122. FULDA. ABBEY CHURCH

HALL CRYPT (817-819)

[after Vonderau, 1949, 52, fig. 6]

The monk Racholf, under Eigil's abbacy, built two crypts,

one before the western, the other beneath the eastern apse of

Ratger's church. Both were destroyed, the west crypt during

construction of the 18th-century church and the east when two

circular towers standing to its side collapsed in 1120-21. This

apse was completely rebuilt (1123-1158) by Markward,

presumably in its original form. Both crypts were dedicated by

Bishop Heistulf of Mainz in 819. (For archaeological details see

Vonderau, 1931, 49-61; for documentary sources the prose and

metric Vita Eigilis, in Mon. Germ. Hist., Script. XV:1,

229, and ibid., Poetae Lat. 11, 108.)

others, of even earlier date—exhibiting the classical truss

formed by tie-beam, rafters, and bracing struts[182] —is engraved

into the masonry gables of the porches of certain

Syrian churches of around 400 (figs. 128 and 129). In Italy

this roof type survived unchanged throughout the Middle

Ages. One of the finest extant examples is the magnificent

fourteenth-century roof of the church of San Miniato al

Monte in Florence.[183]

In conformity with this well-attested Roman and Early

Christian roof tradition, we have reconstructed the roof of

the Church of the Plan as a trussed timber roof with purlins

supporting an outer set of rafters (figs. 108-110). The proportions

of the Church suggest that these trusses were

placed at a distance of 20 feet from one another over the

center of each nave column, or at intervals of 10 feet, if we

assume intermediate trusses over the apex of each arcade

midway between the columns. Our roof pitch is of course

purely conjectural. Since the Church of the Plan lies

stylistically midway between the Early Christian and the

Romanesque, we have constructed it at an angle of 45

degrees—a pitch considerably more obtuse than that of the

average Early Christian roof, yet substantially more acute

than the average roof of the transalpine churches of the

tenth and eleventh centuries.

After Deneux, 1927, 50, figs. 70 and 71. Deneux believes that the

roof of St.-Germain-des-Prés, as he has reconstructed it, dates from

1044. In volume 1 of the series Charpentes, published by the Ministère de

l'éducation nationale, Direction de l'architecture, Centre de recherches

sur les Monuments historiques, the same roof is ascribed to the twelfth

century.

On the dependence of Fulda and Old St. Peter's in Rome, see

Krautheimer, 1942, 8ff and below, pp. 187ff.

Krautheimer, 1942, 24, drew attention to these conditions. The

letter was published in Mon. Germ. Hist., Epist., III, 592ff and 609ff.

On the roof of Old St. Peter's, see Fontana, 1694, 98-99, the source

of our fig. 12; see Rondelet, III, 1862, and Plates, pl. 77, fig. 9; and

Ostendorf, 1908, 77ff.

Vitruvius, De Architectura, Book IV, chap. 2; ed. Krohn, 1912, 80.

To William S. Anderson, at Berkeley, and Sterling Dow of Harvard, I

am indebted for valuable advice in the translation of this chapter and the

interpretation of its technical terms.

"Sub tectis, si maiora spatia sunt, et transtra et capreoli . . . supra

cantherios templa; deinde sub tegulas asseres ita prominentes, uti parietes

proiecturis eorum tegantur" (Vitruvius, loc. cit.).

In many historically known cases of this roof type, the king post

does not even reach down to the tie beam, but stops a short distance

from the upper surface of the tie beam. This happens to be the case in

the trusses of the roof of St. Catherine on Mount Sinai, mentioned below.

A detailed description of this roof by George H. Forsyth will be

found in The Monastery of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai: The Church and

Fortress of Justinian, ed. George H. Forsyth, Ihor Ševčenco, and Kurt

Weitzmann (University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan,

1974). The roof is comprised of thirteen low-pitched and sturdy trusses

connected longitudinally by means of purlins. Its sixth-century date is

attested by a Justinian inscription in one of the tie beams as well as by

radiocarbon tests. For a brief preliminary description and a photographic

reproduction of the interior of the roof, see Forsyth, 1968, 1-19.

See Butler, 1929, 199, figs. 201 and 204 (from which our figs. 20 and

27 are taken). The distance and disposition of these trusses can be

judged by the position of the masonry corbels in the clerestory walls of

many Syrian churches. When the trusses were placed at short intervals,

the roof-covering of tiles and stones could be laid directly upon the

purlins; when the distance was great, the covering was laid upon an

outer set of rafters which rested on purlins, as in Vitruvius's broad-span

roof.

ROOF COVERING

The customary material used for covering the roofs of

Carolingian churches was tile or lead. The distinction is

not always clear, as the term tegula (classical Latin for

"ceramic tile") is used for both. However, it is probably

safe to assume that when tegula is used without the qualifying

adjective plumbea, it stands for tile.

When Benedict of Aniane founded his first monastery at

the banks of the stream of that name, he covered the

building "not with red-gleaming tiles, but with thatch"

(non tegulis rubentibus, sed stramine).[184]

Conversely, when he

rebuilt the monastery in 772, "he covered the houses not

with thatch, but with tiles" (non iam stramine domos, sed

123. PLAN OF ST. GALL

CRYPT OF THE CHURCH

AUTHORS' INTERPRETATION

Whatever the precise shape of the space designated

CONFESSIO it obviously could not have exceeded an area

confined to the north and south by masonry of the

Presbytery walls and to the west and east by walls separating

CONFESSIO from crossing and from the transverse arm of the

corridor crypt. It is also clear that the Crypt's two

longitudinal arms would have come to lie outside the masonry

of the Presbytery walls. To clear these walls they would

each, in construction, be moved outward by 2½ feet; but the

builder could have easily complied with this need, since the

Crypt arms were underground and the space invaded by their

outward displacement would not have diminished any

adjacent structure. The CONFESSIO surely must have been

covered with groin vaults because of the weight of the

superincumbent Presbytery floor with its high altar and

heavy loading from constant use.

In the plan shown to the right Ernest Born has subdivided the 40-foot

squares of crossing and Presbytery internally each into sixteen 10-foot

squares and the latter again (in the areas occupied by the crypt) each into

sixteen 2½-foot squares. Our reconstruction shows how easily and

convincingly the masonry of an actual building can be developed within the

framework of the grid that forms the conceptual basis of the Plan — masonry

and foundation solid enough to carry the load of the superincumbent walls

of the Church.

The CONFESSIO is here interpreted as an inner hall crypt of roughly 20 by

30 feet with a ceiling formed by six groin vaults each covering the surface

area of a 10-foot square (100 square feet).

In the interpretation illustrated here the gray tint indicates walls of the church above

in locations depicted on the original document, and the U-shaped crypt passage or

corridor is presumed to be covered with a barrel vault.

issued by Charlemagne at the synod of Frankfurt in 794,

it appears that tile was then the customary cover for

church roofs.[186] But before the century had come to a close,

lead appears to have moved into the foreground. It was

with tegulis plumbeis that Charlemagne covered the Palace

Chapel at Aachen (consecrated in 805).[187] The same material

was used by Abbot Ansegis (807-833) to cover the church

of St. Peter's at St. Wandrille,[188] by Bishop Hincmar (845882)

to cover the roof of the cathedral of Reims,[189] and by

Einhard to cover the roof of his church of SS. Peter and

Marcellinus, at Seligenstadt (started in 827). The purchase

of lead for the latter and the difficulties encountered in

written to an unidentified abbot:

I am speaking about the conversation we had when, meeting in the

Palace, we talked about the roof of the blessed martyrs of Christ.

Marcellinus and Peter, which I am now trying to build, although

with great difficulty, and a purchase of lead for the price of 50

pounds was agreed between us. But although work at the basilica

has not yet reached the point where I should be concerned with the

necessity of building the roof, yet it always seems that we should

hasten, because of the uncertain span of mortal life, to complete the

good work we have begun, with God's help.[190]

Ibid., 11, No. 41; and Mon. Germ. Hist., Leg. II, Cap. I, ed. Alfred

Boretius, 1883, 76, chap. 26: "Lignamen, et petras sive tegulas, qui in

domus ecclesiarum fuerint."

| The Plan of St. Gall | ||